Feline Herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) Infection

Bioguard Corporation Feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) is a common viral infection in cats that primarily affects the upper respiratory system. It is a major cause of feline viral rhinotracheitis (FVR), which presents symptoms like sneezing, nasal discharge, and conjunctivitis (eye inflammation). FHV-1 is highly contagious among cats and is spread through direct contact with infected saliva, […]

Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Cats

Bioguard Corporation Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) an autosomally recessive inherited neurodegenerative disorder seen in Maine Coon cats. The disease is characterized by weakness and atrophy in muscles due to loss of motor neurons that control muscle movement. Affected cats first show signs of disease around 3–4 months of age. Clinical signs include tremors, abnormal posture, […]

Polycystic Kidney Disease in Cats

Bioguard Corporation Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a chromosomally dominant genetic disorder; it can occur in humans, cats, dogs, and other animals. In the renal cortex and medulla, there are cysts of various sizes and fluid-filled, so it is commonly known as the bubble kidney. Cysts increase in size and number over time, replacing kidney […]

Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

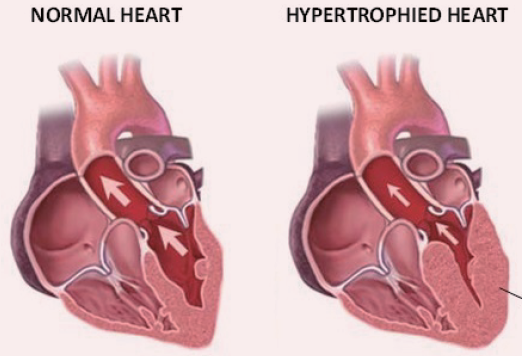

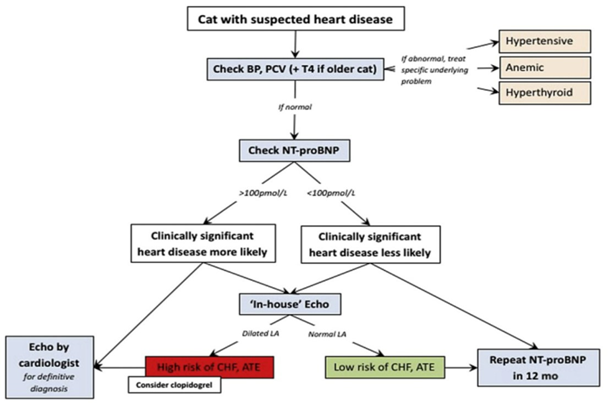

Bioguard Corporation Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary, familial, and hereditary heart condition, and it is the most common heart disease in cats. Its key characteristic is primary concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (thickening of the heart wall), which occurs without pressure overload (such as from aortic stenosis), hormone stimulation (like in hyperthyroidism or acromegaly), myocardial […]

Diagnosis of Feline Respiratory Mycoplasma Infection

Bioguard Corporation In cats, ’mucosal’ mycoplasma infections typically cause ocular and respiratory disease, and less frequently neurological or joint disease. These Mycoplasma species are distinct to the haemotropic mycoplasmas that target red blood cells, causing hemolytic anemia in cats. Mycoplasma felis is typically associated with Upper Respiratory Tract Disease (URTD) in cats. Transmission M. felis […]

Tritrichomonas Infection in Cat

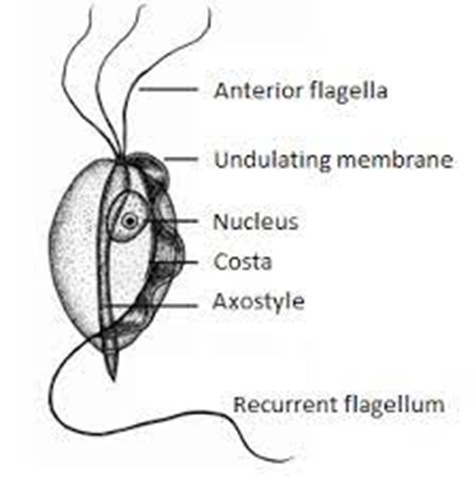

Bioguard Corporation Tritrichomonas foetus is a significant cause of large bowel diarrhea and persistent colitis in cats. These pear-shaped organisms have three anterior flagella and one posterior flagellum. They have a distinctive undulating membrane, which gives them a similar appearance to Giardia. However, they do not form cysts and are transmitted directly from one host […]

Kidney Diseases in Cats

Lloyd Alexandria Chavez, R.M.T Cats possess a pair of kidneys located on either side of their abdomen, playing a crucial role in eliminating waste from their system. These organs are also key in regulating the balance of fluids, minerals, and electrolytes in the body, conserving water and protein, and supporting blood pressure and the […]

Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Cats

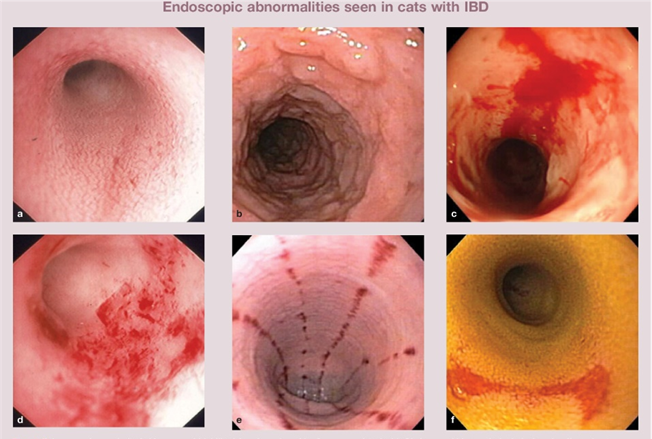

Sushant Sadotra Feline inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic condition that affects a cat’s gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The walls of the GI tract become thickened due to the infiltration of inflammatory cells, disrupting the cat’s ability to digest and absorb food properly. Although IBD can affect cats of any age, middle-aged and older cats […]

Respiratory Tract Disease Complex in Cats

Sushant Sadotra, PhD/Diagnostic specialist Feline respiratory disease (FRD) syndrome or feline upper respiratory tract disease complex is a common infection in cats caused mainly by Feline Herpesvirus (FHV-1), Feline Calicivirus (FCV), Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma spp., and Bordetella bronchiseptica. About 90% of all upper respiratory infections are caused by FHV-1 and FCV. Common Symptoms: · Sneezing · Nasal […]

Introduction to Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Maigan Espinili Maruquin It is important to be aware that some of the diseases your pets may have are actually inherited. In cats, there are myocardial diseases that can be breed- related. The most common myocardial disease in cats is Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), wherein abnormal thickening of the walls of the left ventricle (LV) […]