Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV): A Constant Threat to Our Cat Companion

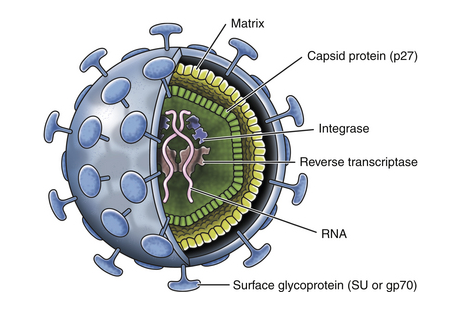

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV): A Constant Threat to Our Cat Companion Maigan Espinili Maruquin It was believed that the Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is the one responsible in most disease- related deaths in cats. It was Jarrett, et al., 1964 who first identified FeLV as a causative agent of the viral infection of cats more than 40 years ago by electron microscopy (EM). However, the prevalence of FeLV as the disease- causing agent in cats has declined, and so is the death rate caused by the infection. Despite FeLV being a threat in the life expectancy of the cats, owners still choose to provide the proper treatment for their cats and proper care, leaving FeLV-infected cats live for many years with good quality of life (Hartmann 2012). Structure and Replication (https://veteriankey.com/feline-leukemia-virus-infection/) Fig. 01. The structure of FeLV containing two identical strands of RNA, reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease inside the capsid protein (p27), surrounded by a matrix and all enclosed by the envelope containing gp70 glycoprotein and the transmembrane protein p15E (https://veteriankey.com/feline-leukemia-virus-infection/). FeLV is approximately 8.4kb in length. It belongs to the genus Gammaretrovirus. Retroviruses have three- layered structure and RNA (two copies of single-stranded RNA), which makes the genetic material, is in the innermost- layer; together with the essential enzymes for its viral activities (including integrase, reverse transcriptase and protease) and nucleocapsid protein. The capsid protein in the middle layer surrounds the genome. And, the outer layer is the envelope from which glycoprotein ‘spikes’ project (Westman, Malik et al. 2019). The envelope spikes are responsible for the attachment of the virus to the target cell surface receptors which also represents an essential target for the host immune response. During replication, RNA is being reverse transcribed into DNA through the enzyme reverse transcriptase. This interrupts the normal cellular flow of genetic information, the Central Dogma, making this enzyme the target of many anti- viral drugs. The synthesized DNA from the RNA integrates into the genome of the target cell as a provirus, which is a required component for the viral replication, assisted by a second viral enzyme, the ‘integrase’. This provirus remains in the genome of the cell and upon cellular division, the provirus is expressed, leading to the production of progeny virions and virus shedding (Lavialle, Cornelis et al. 2013, Willett and Hosie 2013, Chiu, Hoover et al. 2018, Westman, Malik et al. 2019). FeLV Infection On a previous research, there were three important observations following FeLV Infection: (a) some cats can eliminate the virus before it progresses local replication after enough time and appropriate immune response; (b) some cats become persistently viraemic; (c) some cats are viraemic before immunity responds to eliminate the transient viraemia after 2–16 weeks, but not before a latent infection is established as DNA provirus (Westman, Malik et al. 2019). Antigen-negative, provirus positive cats are considered FeLV carriers. This was after cats infected with FeLV were found to remain provirus-positive. Following reactivation, they can act as a source of infection. As FeLV provirus is integrated into the cat’s genome, it is unlikely to be fully cleared over time and possibly in a transcriptionally silent (latent) state. Antigen-negative, provirus-positive cats do not shed the virus, but reactivation is possible (Torres, O’Halloran et al. 2008, Hartmann 2012). FeLV undergoes different stages of infection. On abortive infection, virus starts initial replication but an effective immune response may terminate the viral replication and avoid becoming viraemic by eliminating the FeLV-infected cells (Hofmann-Lehmann, Cattori et al. 2008, Torres, O’Halloran et al. 2008, Hartmann 2012)(Torres, Mathiason et al. 2005). In regressive infection, effective immune response contains the replication of the virus prior to or shortly after bone marrow infection (Hartmann 2012) despite retaining a low level of FeLV-infected cells in circulation and tissues. In some cases, infected cells are also eliminated and undergo abortive infection (Torres, Mathiason et al. 2005). Mainly, virus shed in saliva however, in this infection, viremia is terminated within weeks or months. However, virus undergoes latency since it is not completely eliminated, harboring viral DNA in circulation, and integrating the proviral DNA in the bone marrow stem cells and lymphoid tissues. The proviral DNA is not translated into proteins making it non- infectious. The cats are considered ‘protected’ from the development of viraemia and thus disease, but they remain infected. Under latent infection, viral replication is delayed. Therefore, these regressively infected cats are not infectious to others but the infection could be reactivated when antibody production decreases (Torres, Mathiason et al. 2005, Hofmann-Lehmann, Cattori et al. 2008, Torres, O’Halloran et al. 2008, Hartmann 2012). For the progressive infection, the infection is not contained early, resulting to extensive viral replication. They remain positive after 16 weeks of infection. This makes the cats persistently viraemic and infectious to other cats. They develop FeLV- related diseases, and most of them die within a few years. On the other hand, it is focal or atypical infection if there’s a persistent atypical local viral replication (e.g., in mammary glands, bladder, eyes). This leads to an irregular production of antigen causing alternate results of positive and negative (Hartmann 2012). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis There are two possible results following the first 4 weeks FeLV exposure of the host: (a) failure to contain the viral replication; and (b) successful immune response of the host against the virus (Rojko, Hoover et al. 1982, Hoover and Mullins 1991, Torres, Mathiason et al. 2005). After a long asymptomatic phase, cats can develop clinical signs including tumors, hematopoietic disorders, neurologic disorders, immunodeficiency, immune-mediated diseases, stomatitis, immunosuppression, hematologic disorders, immune-mediated diseases, and other syndromes (including neuropathy, reproductive disorders, fading kitten syndrome). This is determined by a combination of viral and host factors (Hartmann 2012). Mostly, tumors in cats are associated with FeLV, commonly lymphoma and leukemia, less often other hematopoietic tumors and rarely other malignancies (including neuroblastoma, osteochondroma, and others). FeLV vaccination resulted to a major decrease of FeLV infection in the overall

Rapid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing to Combat Resistance

Table of Contents 1. Introduction: Defining Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) is a crucial diagnostic procedure used to guide the treatment of infectious diseases. It provides evidence-based data that allow clinicians and veterinarians to identify the most effective antibiotics for treating specific bacterial infections while minimizing the risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). 1.1 Purpose in Clinical and Veterinary Diagnostics AST is an in vitro laboratory method used to determine which antibiotics are effective at inhibiting the growth of a given bacterial isolate. In clinical microbiology, it functions as a vital extension of the diagnostic process, translating laboratory findings into actionable treatment decisions. The fundamental objectives of AST are threefold: Confirm Susceptibility: To verify that a bacterial isolate is sensitive to the chosen empirical antimicrobial agents. Detect Resistance: To identify emerging or established resistance mechanisms within the isolate. Guide Therapy: To provide clinicians with data that support targeted, rational antimicrobial selection. Although most applications are in human medicine, the relevance of AST extends to veterinary and agricultural diagnostics, where inappropriate or preventive antibiotic use in food and animal industries accelerates the development of resistance. Incorporating AST into these sectors is therefore essential for achieving a One Health approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health management. 1.2 Role in Identifying the Most Effective Antibiotic AST ensures that patients receive the most appropriate and targeted antibiotic therapy. The process combines quantitative and qualitative assessments of bacterial growth inhibition, allowing for the identification of the most suitable antimicrobial agent. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC):A primary output of AST is the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), defined as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic required to inhibit visible bacterial growth in vitro. Determining Efficacy:MIC values are interpreted to determine whether the bacterial isolate is susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to a given antibiotic. Standardization and Global Guidelines:The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) establish standardized interpretive breakpoints that guide laboratory and clinical decisions globally. Integration for Complete Diagnosis:The diagnostic value of AST is maximized when combined with accurate bacterial identification. This integration enables physicians and veterinarians to administer the narrowest effective antibiotic for the identified pathogen, optimizing therapeutic outcomes and minimizing ecological impact. 1.3 Supporting Antimicrobial Stewardship and Reducing Misuse AST forms the cornerstone of antimicrobial stewardship, the coordinated effort to preserve antibiotic efficacy by promoting rational use. The global threat of antibiotic resistance, which currently contributes to an estimated 700,000 deaths annually, underscores the urgency of this practice. Reducing Broad-Spectrum Dependence:In many clinical scenarios, delays in diagnostic confirmation lead clinicians to initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics empirically. This practice, while often necessary, fosters selective pressure that accelerates resistance. Enabling Rapid, Targeted Treatment:Improvements in AST turnaround time and the adoption of rapid testing methods allow faster initiation of effective targeted therapy, reducing unnecessary broad-spectrum exposure. Improving Clinical Outcomes:Timely susceptibility results enable healthcare professionals to transition from empirical to pathogen-directed therapy. This precision approach improves patient recovery, reduces adverse effects, and contributes to long-term containment of resistance. 2. Principles and Methods of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) encompasses a range of laboratory methods designed to determine the ability of bacteria to grow in the presence of specific antimicrobial agents. These techniques are broadly divided into phenotypic methods, which measure the observable inhibition of bacterial growth, and genotypic methods, which detect genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance. 2.1 Phenotypic Methods Phenotypic testing remains the gold standard for AST in clinical and veterinary microbiology. These methods directly assess bacterial growth inhibition and provide either qualitative or quantitative results based on visible morphological changes. Disk Diffusion (Kirby–Bauer Test) The disk diffusion method, commonly known as the Kirby–Bauer test, is one of the most widely used AST procedures worldwide due to its convenience, low cost, and standardized interpretive criteria. Principle and Procedure:Sterile paper disks impregnated with fixed concentrations of antibiotics are placed on the surface of an agar plate uniformly inoculated with the bacterial isolate. Following incubation (typically 16–24 hours at 35 °C), bacterial growth is inhibited around the disk, forming a zone of inhibition. Interpretation:The diameter of the inhibition zone is measured and compared with reference standards provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) or the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). The isolate is categorized as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on these standardized breakpoints. Advantages and Limitations:The disk diffusion test allows simultaneous testing of multiple antibiotics but provides qualitative results only, as it does not yield an exact Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). Broth Dilution (Macro and Micro Methods) Broth dilution techniques determine the MIC, defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits visible bacterial growth. Macrobroth (Tube) Dilution:This traditional method involves preparing serial two-fold dilutions of antibiotics in test tubes containing a liquid growth medium. After inoculation and incubation at 35 °C, tubes are examined for turbidity. The lowest concentration preventing visible growth represents the MIC. While reliable, this approach is labor-intensive and time-consuming, limiting its routine clinical use. Broth Microdilution:This method miniaturizes the macrobroth technique using 96-well microtiter plates, allowing the simultaneous testing of multiple antibiotics and bacterial isolates. Each well contains a defined concentration of antibiotic and a standardized inoculum. After incubation, bacterial growth is assessed visually or via automated readers. Automation: Broth microdilution forms the foundation of most automated AST systems, which have been in routine diagnostic use since the 1980s. Systems such as VITEK® 2, BD Phoenix™, Sensititre™, and MicroScan WalkAway® automate sample handling, incubation, and interpretation, improving standardization and efficiency. Turnaround Time: Although miniaturized, conventional broth microdilution typically requires similar incubation times to macrobroth methods (16–24 hours). E-test (Gradient Diffusion Method) The E-test provides a semi-quantitative estimate of the MIC by combining diffusion and dilution principles. Principle and Procedure:A plastic strip impregnated with a continuous antibiotic gradient is placed on an agar plate inoculated with the test organism. After 18–24 hours of incubation, an elliptical inhibition zone forms around the strip. Interpretation:The MIC is read directly from the point on the scale where the inhibition

Canine Parvovirus

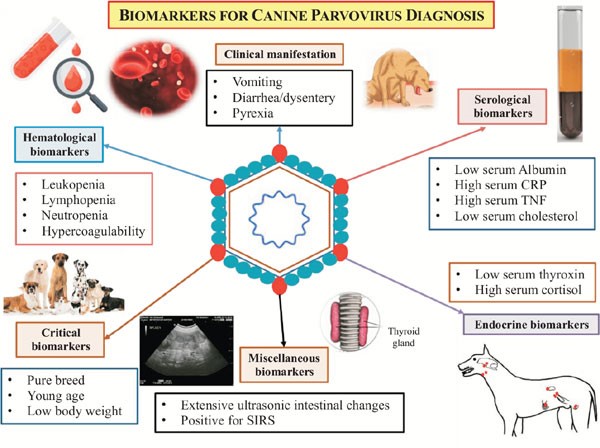

Canine Parvovirus CHINESE EDITION IS WRITTEN BY DR. WANG, SHIH-HAO / ENGLISH EDITION IS TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY DR. LIN, WEN-YANG (WESLEY) Abstract The canine parvovirus (CPV) is a common, acute, high morbidity and high morality virus that mainly infect canine population. This virus possess highly survival rate for 5 weeks in the natural environment. It is highly contagious and easily transmitting among canine population by the fecal-oral route through contacting contaminated feces. CPV usually attack digestive system. Sometimes it may induce myocarditis among canine and cause sudden death. All ages, sexes and breeds of dogs could be susceptible to CPV, especially puppies. Clinical sighs of infected dogs may include fever, lethargy, continuous vomiting, continuous diarrhea, stinky viscous diarrhea with blood, dehydration and abdominal pain etc. Canine show signs of the disease would usually die within 3 to 5 days. There are no specific drugs for curing CPV until now. Supportive care such as consuming water-electrolyte fluid is the only present solution to maintain physiological function and relieve symptoms. The infected canine should have medical care as soon as possible; otherwise, more severe conditions like acute dehydration, hypovolemic shock, bacterial infections and death will occur. Infection prevention measures include environmental disinfection and routine vaccines. Pathogens The canine parvovirus (CPV) is an ssDNA virus, which belongs to the species carnivore protoparvovirus 1 within the genus protoparvovirus in the family parvovirus (parvoviridae). CPV is 98% identical to feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV) with variant in six coding nucleotide of structural proteins VP2: 3025, 3065, 3094, 3753, 4477, 4498 that makes CPV-2 infect canine host instead of replicating in cats. Two types of canine parvovirus were discovered – canine minute virus (CPV1) and CPV2, both can attack canine population and canidae family such as raccoons, wolves and foxes. Canine parvovirus may be susceptible to cats without pathogenic, and it is an inapparent infection. CPV2 could stably survive in feces for 5 months with ideal condition. Furthermore, CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c type viruses have been isolated and sequenced from animals. Other than targeting on canine, large cats are susceptible to CPV-2a, CPV-2b. CPV-2c type viruses have high prevalence on infecting leopard cats. Figure 1. Model of CPV evolution showing VP2 amino acid differences between each virus and indicating the virus host ranges. (Karla M. Stucker, Virus Evolution In A Novel Host: Studies Of Host Adaptation By Canine Parvovirus, Published in 2010) Epidemiology In 1978, a novel infectious canine disease was firstly occurring in the east coast of America. Within 12 months, scientists identified CPV-2 as the aetiological key of severe symptoms among canine. Due to characters of highly contagious and potential environmental resistance, CPV-2 spread swiftly over entire USA, European countries, Australia and Asia. In 1978, canine parvovirus also invade among canine in Taiwan. Therefore, CPV caused large scale of canine death at the early stage of pandemic. By the establishment and development of CPV vaccine, global wide spreading of CPV has been rarely happen today. However, canine parvovirus still widely exists in domestic dogs and wild canidae. It became one of the canine endemic disease. Pathogenesis Incubation period of CPV-2 lasts 4 to 5 days. The virus mostly attacks rapidly dividing cells especially lymphopoietic tissues, the bone marrow, crypt epithelia of the jejunum, ileum and (in young dogs under 4 weeks old) myocardial cells. Rottweilers, black Labrador Retrievers, Doberman Pinschers, and American Pit Bull Terriers are more susceptible than other species; once they are infected, would suffer severer conditions. Besides, CPV-2 take the major place to affect canine and wild canids. After entering into hosts’ body, CPV-2 firstly replicates in oropharynx lymphoid tissues, mesenteric lymph nodes and thymus gland, then spreading to other lymph nodes, lung, liver, kidney and rapidly dividing tissues (e.g. bone marrow, intestinal epithelial cell and myocardial cell) by the blood stream. 4 to 5 days after, clinical sighs like diarrhea, vomiting, lymphopenia, anorexia, depression, dehydration, hypothermia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia would appear. Severe dehydration and hypovolemic shock may happen due to lose large amount of fluid and protein by vomiting and diarrhea. Transmission Fecal-oral route is the main transmission pathway of CPV-2. Large amount of virus would be detected in feces of infected canine within 1 to 2 weeks of acute phase. An infected pregnant canine could transmit virus to fetus through placenta. Fomites include contaminated shoes, cages, food bowls and other utensils could serve as CPV transmitting objects also. Clinical forms There are four clinical forms according to distinct signs and lesions: enteric, myocardial, systemic infection and inapparent Infection. A. Enteric form : It is known that CPV-2 caused enteritis symptoms. This form infect host with low virus titers (around 100 TCID50). Symptoms in initial stage are sopor, loss of appetite, acute diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, slight elevated body temperature, frailty and acting like in extreme pain. Severity of illness vary according to the age of canine, healthy condition, infectious dose of the virus, and other pathogens in intestine and so on. Typical signs of CPV induced enteritis and its course include loss of appetite, sopor, fever (39.5℃-41.5℃) within 48 hours follow vomiting. 6 to 24 hour after vomiting follow watery stool in yellow or white color, mucus stool or bloody stool with stench in severe cases. Due to consistent diarrhea and vomiting, dogs suffer worsen dehydrated condition. Common clinical pathologic examination consist assessing dehydrated condition and significant decreasing of white blood cell of dogs (400 to 3000 /μL). B. Myocardial form: This form only appear in puppies around 3 to 12 weeks of age. Major cases show pups’ age under 8 weeks. Mortality rate is extremely high with myocardial form (almost up to 100%). Clinical signs include irregular breathing, cardiac arrhythmia. Collapse, hard breathing may happen to acute cases follow death within 30 minutes. Most cases would die within 2 days. The subacute form would also die from hypoplastic heart syndrome within 60 days. Nevertheless female adult canine acquire antibodies against myocardial form by vaccination or infection, puppies may

Peritonitis in Dogs: Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment Insights

Table of Contents 1. Introduction to Peritonitis and Septic Peritonitis (SP) Definition of Peritonitis Peritonitis in dogs refers to the inflammation of the peritoneum, the thin serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity and envelops the visceral organs. When this inflammation is accompanied by microbial contamination, the condition progresses to septic peritonitis (SP), a complex, rapidly progressive, and life-threatening disease. SP represents a convergence of local peritoneal inflammation and systemic infectious insult, frequently culminating in sepsis or septic shock without timely intervention. Relevance Across Mammalian Species The pathophysiological patterns of septic peritonitis exhibit strong parallels across mammalian species. Data derived from canine, feline, and human literature suggest similar clinical trajectories and diagnostic challenges: Canine–Feline Parallels:Evidence indicates that clinicopathologic abnormalities and outcomes in feline SP mirror those documented in dogs, reinforcing the cross-species applicability of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Human Literature as a Clinical Framework:Human medicine, with its extensive sepsis research, provides a valuable framework for veterinary clinicians. The early adoption of Procalcitonin (PCT) as a biomarker in dogs reflects its well-established role in human sepsis diagnosis.The central mechanism, an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune responses, is widely corroborated by human critical care studies and applies equally to canine SP. Peritonitis Arises Most Commonly from Infection and Perforation Microbial contamination of the peritoneal cavity most frequently results from gastrointestinal perforation, loss of mucosal integrity, or traumatic breach of sterile abdominal compartments. Microbial Etiology Gram-negative organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, predominate in septic abdominal infections: In one study of dogs with septic peritonitis: 39 percent of abdominal cultures yielded only gram-negative bacteria, 28 percent yielded only gram-positive organisms, and 33 percent demonstrated mixed gram-negative and gram-positive infections. Common Sources of Contamination Septic peritonitis is usually linked to a definable intra-abdominal lesion or event: Gastrointestinal leakage, including dehiscence of enterotomy or enterectomy sites, remains one of the most frequent causes. NSAID-induced perforation: Meloxicam-associated colonic perforation is documented, marked by full-thickness ulceration and underlying vascular thrombosis, culminating in diffuse septic peritonitis. Parasitic migration and necrosis: Aberrant migration of Spirocerca lupi may induce acute mesenteric ischemia-like lesions, leading to segmental necrosis, infarction, and SP. In one case series, all affected dogs were ultimately diagnosed with septic peritonitis. These pathways highlight the diversity of initiating events while reinforcing the consistent pathogenic mechanism, the introduction of bacteria or fungi into a previously sterile compartment. Importance of Rapid Recognition and Progression Toward Shock Septic peritonitis is characterized by abrupt clinical deterioration. Early recognition and decisive intervention are central to improving survival. Life-Threatening Pathophysiology Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction arising from a dysregulated host response to infection. SP is a major precipitating cause of sepsis in veterinary practice. Rapid Clinical Decline The literature consistently stresses the importance of early diagnosis: Delayed detection directly decreases survival, as timely intervention is essential for controlling contamination and stabilizing systemic physiology. Dogs with bacterial SP frequently fulfill Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria due to their pronounced inflammatory cascade. Progression to Septic Shock SP-associated sepsis may escalate to septic shock, defined by: Persistent arterial hypotension despite aggressive fluid resuscitation Requirement for vasopressor therapy to achieve adequate perfusion pressure In one study, 25 percent of dogs with bacterial sepsis progressed to septic shock requiring vasopressors, reflecting the severe systemic compromise associated with SP. Mortality and Organ Dysfunction Survival outcomes correlate strongly with: The number of organ systems affected, and The severity of organ dysfunction, often progressing to Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS). Even with appropriate surgical and medical management, only approximately half of affected dogs survive to hospital discharge, underscoring the lethal nature of this condition. 2. Etiology and Pathophysiology The etiology and pathophysiology of peritonitis, particularly the infectious variant known as septic peritonitis (SP), describe a cascade in which localized abdominal contamination progresses toward systemic inflammatory crisis. Across studies in dogs, this transition is consistently associated with high morbidity, rapid deterioration, and the need for aggressive diagnostic and surgical intervention. 2.1 Overview of Pathogenesis Septic peritonitis is considered a complex, life-threatening condition, initiated by microbial contamination of the peritoneal cavity and sustained by a dysregulated inflammatory response requiring urgent perioperative management (Mueller et al., 2001). Microbial Contamination of a Sterile Space The entry of bacterial or fungal pathogens into the previously sterile peritoneal cavity represents the defining initiating event. Most common pathogens:Gram-negative organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, are the predominant cause of abdominal sepsis in dogs (Costello et al., 2004). Culture patterns:In one study of canine SP, 39 percent of abdominal effusion cultures yielded only gram-negative bacteria, 28 percent only gram-positive, and 33 percent yielded both, demonstrating the polymicrobial nature of abdominal contamination (Mueller et al., 2001). Sources of Contamination Peritoneal contamination may arise through multiple mechanisms: Surgical Dehiscence The most common cause of SP in dogs in a retrospective study (43 dogs) was dehiscence of an enterotomy or enterectomy site, indicating failure of previous surgical repair (Costello et al., 2004). Ulcer Perforation (NSAID-Induced) Colonic perforation resulting in generalized septic peritonitis has been linked to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) administration, notably meloxicam. Histopathology typically shows full-thickness ulceration, inflammatory infiltration, and perforation with thrombosed vessels at ulcerated sites (Kine et al., 2019). Parasite-Induced Rupture and Ischemia Acute mesenteric ischemia-like syndrome due to suspected Spirocerca lupi aberrant migration causes severe mesenteric vascular thrombosis, intraluminal parasite larvae, and segmental intestinal necrosis. All dogs in one case series ultimately developed septic peritonitis as a result (Lerman et al., 2019). Other Septic Sources Reported infectious causes of systemic sepsis in small animals include: generalized septic peritonitis, pneumonia, pyometra, septic bile peritonitis, and necrotising fasciitis (DeClue et al., 2011). Inflammatory Cascade and Systemic Crisis Once microbial contamination occurs, a pronounced inflammatory cascade leads to: exudation and vascular leakage, accumulation of protein-rich abdominal effusion, endotoxin-driven vascular instability, and systemic toxemia. Sepsis develops when this inflammatory response becomes dysregulated, producing an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (Culp et al., 2009). The resulting pro-inflammatory shift damages tissues, promotes coagulopathy, disrupts perfusion, and accelerates multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Septic shock is

Feline Blood-Types

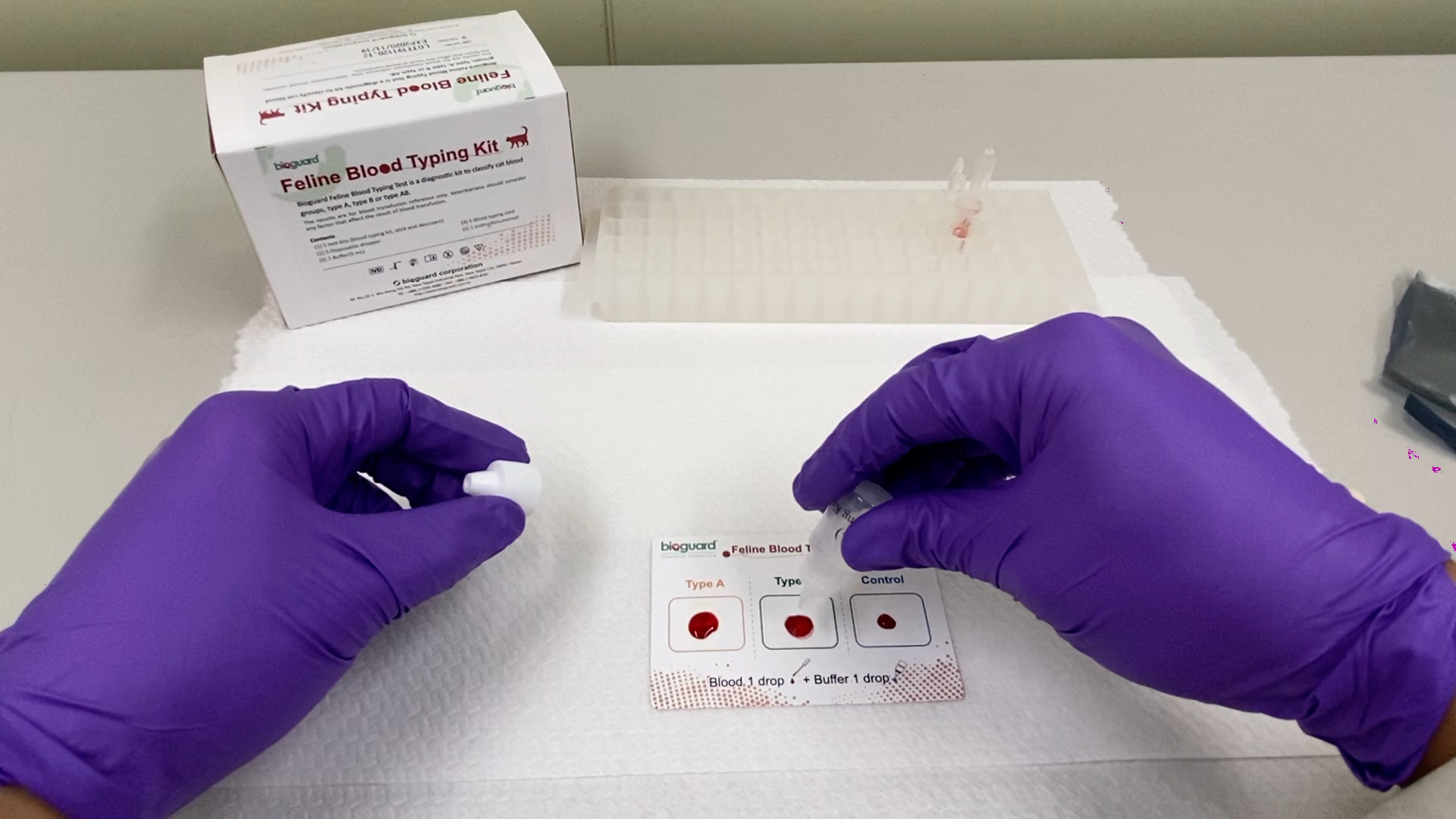

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Feline Blood-Types Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Like humans, cats have blood grouping. However, cats do not have the blood-type O positive. The blood type classification of cats, however, is currently based on the AB system, but like dogs, there are other antigens besides the AB system , such as the Mik blood type. The blood type of cats is composed of mainly A, B, and AB. Type A is the most common, type B is rarer, and type AB is rarest. About 95% of domestic cats are type A blood, and some varieties such as exotic short-haired cats, British short-haired cats, Persian cats, and Scottish folds have a higher percentage of type B blood. As mentioned, the blood-type of cats is mainly A, B, or AB. Peculiarly for AB type, other blood types have innate antibodies. Unlike dogs, cats have antibodies against “non-self” or foreign erythrocytes that can cause lethal immuno -reaction. Therefore, cats cannot obtain a “wrong” blood of different blood types. Before any blood transfusion clinically, cat blood typing is extremely important. Incompatibility of blood type can lead to fatal acute hemolysis reaction, particularly, the blood of a type A cat was given to a type B cat. The anti-type B antibodies found in type A cats have weaker affinity towards each other, causing a mild immune response. However, type B cats have a strong affiliated anti-type A antibody, which can cause a strong immune response. Once type B cat transfuses A-type blood, the red blood cells are rapidly destroyed,resulting in intravascular hemolysis. As little as 1 ml of type A cat blood, it is enough to cause a serious immune reaction in type B cat and then causes absolute lethality. Keep in mind that blood typing is not only extremely vital prior a blood transfusion, but also for cat breeding! Neonatal isoerythrolysis (NI) occurs when a mommy cat with type B blood gives birth to kittens with type A or AB blood and breast-feed them with a high chance of having antigens of type A blood antibodies in the milk, which can cause a severe hemolysis reaction in the kittens. There are no obvious clinical signs to severe hemolytic anemia, but only subtle symptoms such as hemoglobinuria and jaundice. Therefore, we must pay attention to the blood type of the parent before breeding. Despite the best of efforts to prevent them, transfusion reactions may still happen. Depending on the severity, therapy can include glucocorticoids, epinephrine, IV fluids, and discontinuing the transfusion. Fever is usually mild, requiring no treatment. Furosemide should be administered if volume overload occurs. The blood product can be warmed to no more than 37 ° C if hypothermia occurs. Crossmatching blood is the best means of preventing immune-mediated transfusion reactions even if the blood type is known for both cats. It is also imperative blood be collected and administered as aseptically as possible and cats receiving blood products are monitored carefully. The distribution of feline blood types varies by geographic region and breed (Table 1) 1-2. Type-A is the most common type among most cats. There is, however, geographic variation in the prevalence of type-B domestic shorthaired cats. Over 10% of the domestic shorthair cats in Australia, Italy, France and India are type- B. Breed distribution does not vary as much by location because of the international exchange of breeding cats. Over 30% of British Shorthair cats, Cornish and Devon Rex cats, and Turkish Angora or Vans have type-B blood. In contrast, Siamese and related breeds are almost exclusively type-A. Ragdoll cats appear to be unique regarding blood types. Approximately 3.2% of Ragdoll cats are discordant for blood group when genotyping is compared to serology, necessitating further investigation in this breed. Table 1: Selected Blood Type A and B Frequencies in Cats (ignoring AB blood types) The AB blood type is very rare while the frequency of the MiK blood type is unknown. The presence of red blood cell antigens in addition to the AB group may explain why transfusion compatibility is not guaranteed by blood typing; crossmatching is recommended prior to any transfusion 3. Breeding queens, along with blood donors and, if possible, blood recipients should be blood typed. Feline blood-typing methods There are various methods are that can be used to determine blood type, both in a laboratory and veterinarian clinic. Usually in a diagnostic laboratory, they would use various serological methods by adding reagents to samples of blood and observe for any agglutination reactions marking a positive result. In addition, genetic testing is now available to identify blood types A and B using buccal swabs, although it cannot distinguish between A and AB blood groups. In veterinarian clinics, testing may be performed using a card typing system (BIOGUARD® Feline blood -typing kit, New Taipei City, Taiwan and Rapid Vet-H®, Flemington, NJ). If the card-typing system is used, type-AB and type-B results should be confirmed by a referral laboratory as some cross-reactions have been known to occur. Recently,there was an introduction to an alternative novel method for blood typing ie using the gel column agglutination test (DiaMed-Vet® feline typing gel, DiaMed, Switzerland). This test is easier to interpret than the card method, although it requires a specially designed centrifuge that may be cost-prohibitive in some settings. An evaluation of various blood typing kits and methods revealed that accuracy of blood type must be high and working hand in hand with time efficiency. A complete comparison of kits and methods for blood typing is as follow.An evaluation of various blood typing kits and methods revealed that accuracy of blood type must be high and working hand in hand with time efficiency. A complete comparison of kits and methods for blood typing is as follow.An evaluation of various blood typing kits and methods revealed that accuracy of blood type must be high and working hand in hand with time efficiency. A complete comparison of kits and methods for blood typing is

Antibiotic Resistance and Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bacteria

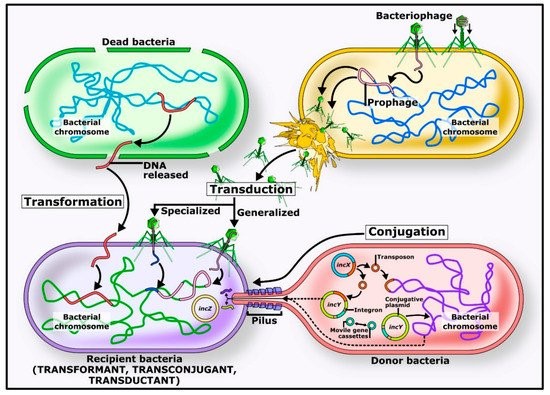

Table of Contents Introduction to Antibiotic Resistance Antimicrobial compounds, including natural and synthetic antibiotics, have been crucial in combating infections. Antibiotic resistance, however, has risen rapidly, threatening public health. Resistance can develop through mutations or acquisition of resistance genes via horizontal gene transfer, which has become the primary driver of the current antimicrobial resistance pandemic. Origins of Antibiotic Resistance Antibiotic resistance is ancient, arising from interactions between organisms and their environment. Many antibiotic-producing bacteria, such as Streptomyces species, carry self-resistance mechanisms. Environmental non-antibiotic-producing bacteria have also evolved resistance to survive alongside these producers. Even ancient permafrost samples reveal genes resistant to β-lactams, tetracyclines, and glycopeptides, showing the long-standing presence of resistance genes. (https://share.google/images/BHfaQxPqmbpyS3GPC) Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer Conjugation Conjugation involves direct transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another, often via plasmids. Plasmids carrying mobile genetic elements such as transposons or integrons spread resistance genes across bacterial populations, including clinically important genes like blaCTX-M and quinolone resistance genes. Transformation In transformation, bacteria uptake DNA fragments from their environment. For instance, penicillin and streptomycin resistance genes were transferred between Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in early experiments, demonstrating this mechanism’s role in spreading resistance. Transduction Transduction occurs when bacteriophages transfer DNA between bacteria “by accident.” This process contributes to resistance evolution in species like Staphylococcus aureus and other clinically relevant bacteria. Environmental Factors and Antibiotic Use Widespread antibiotic use in medicine, agriculture, and aquaculture accelerates resistance by increasing selective pressure. Most antibiotics are excreted unchanged into the environment, creating hotspots for resistance gene transfer. Increased selection pressure has also accelerated horizontal gene transfer and the abundance of resistome elements. Conclusion Horizontal gene transfer—including conjugation, transformation, and transduction—is key to spreading antibiotic resistance genes among bacteria. Understanding these mechanisms is critical to combating the rise of resistant pathogens and protecting public health. To support responsible antibiotic use, Bioguard offers the miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer, a tool designed to help combat antimicrobial resistance with game-changing features: Feature Benefit Fast Results Get results in just 6 hours, enabling swift and confident treatment. Automated Interpretations Instantly deliver precise susceptibility profiles, supporting faster, more informed clinical decisions and optimizing patient care. Dual-Sample Testing Double the efficiency with simultaneous analysis of two samples at once. High Accuracy Achieve an impressive 92% accuracy rate compared to traditional disc diffusion tests. 📌 Note for Veterinarians:The miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer is available exclusively to licensed veterinary clinics and hospitals. 📩 How to Order miniAST To purchase miniAST or request a quotation, please contact our sales team or email our customer service:📧 service@bioguardlabs.com☎️ Please include your hospital name and contact number so our sales representative can follow up with you directly. Source: Akrami F, Rajabnia M, Pournajaf A. Resistance integrons; A Mini review. Caspian J Intern Med. 2019. 10(4):370-376. Babakhani S, Oloomi M. Transposons: the agents of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. J Basic Microbiol. 2018. 58(11):905-917. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201800204. Epub 2018 Aug 16. Barka EA, Vatsa P, Sanchez L, Gaveau-Vaillant N, Jacquard C, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Klenk HP, Clément C, Ouhdouch Y, van Wezel GP. Taxonomy, Physiology, and Natural Products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2015. 80(1):1-43. Barlow M, Hall BG. Phylogenetic analysis shows that the OXA beta-lactamase genes have been on plasmids for millions of years. J Mol Evol. 2002. 55(3):314-21. Barlow M. What antimicrobial resistance has taught us about horizontal gene transfer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009. 532:397-411. Bello-López JM, Cabrero-Martínez OA, Ibáñez-Cervantes G, Hernández-Cortez C, Pelcastre-Rodríguez LI, Gonzalez-Avila LU, Castro-Escarpulli G. Horizontal Gene Transfer and Its Association with Antibiotic Resistance in the Genus Aeromonas spp. Microorganisms. 2019. 7(9). Cabello FC. Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: a growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ Microbiol. 2006. 8(7):1137-44 Clark CA, Purins L, Kaewrakon P, Focareta T, Manning PA. The Vibrio cholerae O1 chromosomal integron. Microbiology. 2000. 146 ( Pt 10):2605-2612.. Datta N, Hughes VM. Plasmids of the same Inc groups in Enterobacteria before and after the medical use of antibiotics. Nature. 198. 306(5943):616-7. D’Costa VM, McGrann KM, Hughes DW, Wright GD. Sampling the antibiotic resistome. Science. 2006. 311(5759):374-7. D’Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW, Schwarz C, Froese D, Zazula G, Calmels F, Debruyne R, Golding GB, Poinar HN, Wright GD. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature. 2011. 477(7365):457-61 Economou V, Gousia P. Agriculture and food animals as a source of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Infect Drug Resist. 2015. 8:49-61. Graham DW, Olivares-Rieumont S, Knapp CW, Lima L, Werner D, Bowen E. Antibiotic resistance gene abundances associated with waste discharges to the Almendares River near Havana, Cuba. Environ Sci Technol. 2011. 45(2):418-24. Griffith F. The Significance of Pneumococcal Types. J Hyg (Lond). 1928. 827(2):113-59. Haaber J, Penadés JR, Ingmer H. Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2017. 25(11):893-905. Harford N, Mergeay M. Interspecific transformation of rifampicin resistance in the genus Bacillus. Mol Gen Genet. 1973. 120(2):151-5. Hotchkiss RD. Transfer of penicillin resistance in pneumococci by the desoxyribonucleate derived from resistant cultures. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1951;16:457-61. Hyder SL, Streitfeld MM. Transfer of erythromycin resistance from clinically isolated lysogenic strains of Streptococcus pyogenes via their endogenous phage. J Infect Dis. 1978. 138(3):281-6. Knapp CW, Dolfing J, Ehlert PA, Graham DW. Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940. Environ Sci Technol. 2010. 44(2):580-7. Kristensen BM, Sinha S, Boyce JD, Bojesen AM, Mell JC, Redfield RJ. Natural transformation of Gallibacterium anatis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012. 78(14):4914-22. Machado E, Coque TM, Cantón R, Sousa JC, Peixe L. Antibiotic resistance integrons and extended-spectrum {beta}-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered from chickens and swine in Portugal. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008. 62(2):296-302. Mazaheri Nezhad Fard R, Barton MD, Heuzenroeder MW. Bacteriophage-mediated transduction of antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2011. 52(6):559-64. Nandi S, Maurer JJ, Hofacre C, Summers AO. Gram-positive bacteria are a major reservoir of Class 1 antibiotic resistance integrons in poultry litter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004. 101(18):7118-22. Partridge SR, Tsafnat G, Coiera E, Iredell JR. Gene cassettes and