Breed-related disease: Great Dane

John K Rosembert The Great Dane, also known as the German Mastiff or Apollo of dogs, a giant breed of German origin. The Great Dane descends from hunting dogs thought to have been around for more than 400 years, and is one of the largest breeds in the world. In the middle of the 16th century, the nobility in many countries of Europe imported strong, long-legged dogs from England, which were descended from crossbreeds between English Mastiffs and Irish Wolfhounds. They were also popular with the upper class for sport, as few other dogs could bring down a wild boar. The Great Danes that were more like those we know today were developed in the 1800s. In 1880, the Germans banned the name “Great Dane” and called the breed “Deutsche Dogge,” which means German mastiff; however, the breed continues to be called Great Dane in English speaking countries. The Great Dane’s large and imposing appearance belies its friendly nature. They are known for seeking physical affection with their owners, and the breed is often referred to as a “gentle giant”. They are moderately playful, affectionate and good with children. They will guard their home. Great Danes generally get along with other animals, particularly if raised with them, but some individuals in the breed can be aggressive with dogs they do not know. There’s one unfortunate truth that Great Dane lovers must come to grips with — this giant breed doesn’t have a long lifespan. Danes don’t fully mature until about the age of 3, but while a smaller dog is middle-aged at 10, that’s very old age in the Dane. Here we gather most common disease of the Great Dane; Gastric Torsion _ Better known as bloat, gastric torsion occurs when the stomach twists, causing the abdomen to swell and stopping blood circulation. Bloat is a red-alert emergency, as the dog dies painfully within hours without surgical intervention. It’s the primary killer of Great Danes, and while other deep-chested breeds are at risk, the level of risk is highest for this breed, according to the Great Dane Club of America. Heart Disease _ Cardiomyopathy, a heart muscle disease, often plagues Danes. Likely genetic in origin, dilated cardiomyopathy cause heart enlargement. Unfortunately, the initial symptom may be the dog’s death, but if your dog develops difficulty breathing, take him to the vet. Danes are also subject to tricuspid valve disease, a congenital problem in which a heart valve doesn’t work properly. Mitral valve disease may cause the left side of the heart to fail. Hip Dysplasia _ Hip dysplasia often manifests itself in larger dog breeds and Great Danes fit the bill. Hip dysplasia is a chronic condition in which the head of the femur bone doesn’t fit into the hip socket correctly. If you adopt a Great Dane from a breeder, ask for radiographs of the parents’ hips and speak to them about the parents’ health history. Hypothyroidism _ This lack of thyroid hormone causes weakness, lethargy, hair loss and other subtle symptoms. If you feel your Dane is just not quite right but can’t put your finger on it, hypothyroidism could be the cause. Take him to the vet for testing. There’s good news for this medical problem — treatment consists of thyroid supplementation. Sources: https://pets.thenest.com/wobbler-disease-doberman-pinscher-5075.html https://www.hillspet.com/dog-care/dog-breeds/great-dane#:~:text=The%20Dane%20is%20German%20in,guardians%20of%20estates%20and%20carriages Photo Credit: https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/great-dane/

Fulminant Tritrichomonas foetus ‘feline genotype’ infection in a 3-month old kitten associated with viral co-infection

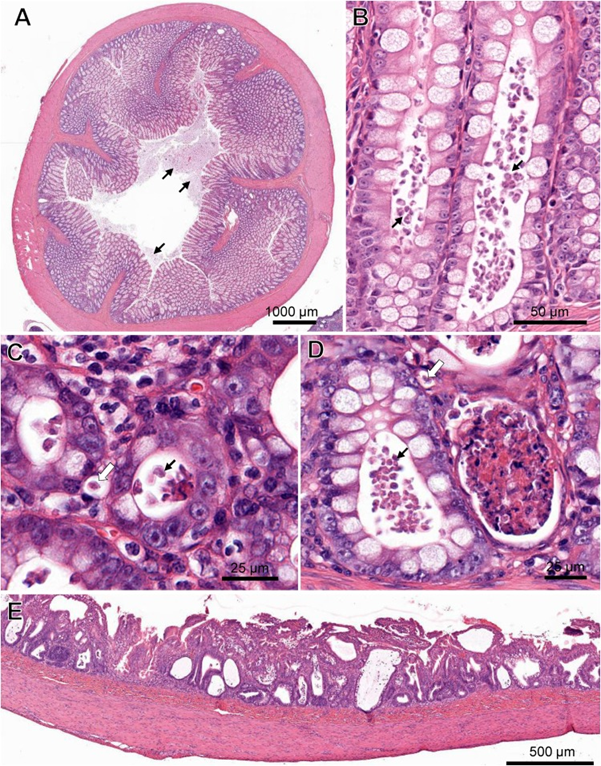

Laura Setyo, Shannon L. Donahoe, and Jan Šlapeta Original article: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.12.007 Tritrichomonas foetus is a microscopic single-celled flagellated protozoan parasite which mainly causes colitis (large bowel diarrhea) in young cats and kittens. A 3-month-old Bengal kitten showed severe T. foetus infection of the colon, cecum and ileum with concurrent feline enteric coronavirus (FCoV) and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). The kitten had an 8-day history of vomiting, diarrhoea, failure to thrive and coughing prior to being presented to the University of Sydney Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Protozoa filling the lumen and crypts and occasional invading into lamina propria were identified within the affected colon and confirmed by PCR as T. foetus‘feline genotype’. FCoV and FPV co-infection were also identified from fecal samples of the kitten via PCR. Immunosuppression caused by FPV may play a role in the unprecedented T. foetus infection intensity observed histologically. Gastrointestinal pathology in a cat co-infected with Tritrichomonas foetus, feline enteric coronavirus (FCoV) and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). (A) Cross-section of the colon with marked protozoal (T. foetus) luminal infiltrate (arrows). ( B) Numerous teardrop-shaped T. foetus overlying the mucosal luminal surface of a crypt of Lieberkühn in the colon. (C) T. foetus (arrow) in the cross-section of the crypts of the colon. (D) Crypt abscesses containing cellular and karyorrhectic debris and T. foetus (arrows) in the colon. Note the invading T. foetus in the lamina propria (arrow outlines). (E) Severe attenuation of the superficial epithelium of the small intestinal of the cat PCR positive for FCoV and FPV. H&E. (Virtual Slide for Virtual Microscopy: VM05606).

Serum Canine Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity Assay (cPLI) in Diagnosing Canine Pancreatitis

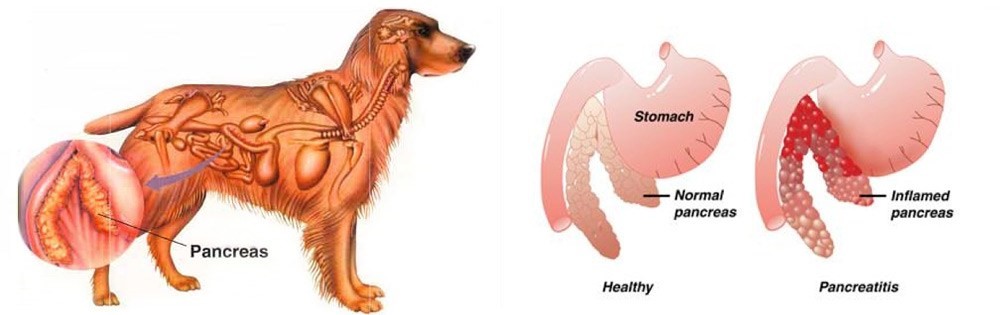

Maigan Espinili Maruquin The lipases are present from a variety of cells, including pancreatic, hepatic, and gastric cells, with similar function, ie , hydrolysis of triglycerides (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012)( Steiner JM, 2000)(Dröes and Tappin 2017). From the pancreatic origin, the canine pancreatic lipase increases in the event of pancreatic inflammation (Steiner and Williams 2003, Haworth, Hosgood et al. 2014). The canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) assay was first a radioimmunoassay, and subsequently an enzyme immunoassay, eventually developed into a commercially available specific canine pancreatic lipase assay (Steiner, Teague et al. 2003, Steiner and Williams 2003, Haworth, Hosgood et al . 2014). The serum cPLI is now used as an important specific, and sensitive marker for the exocrine pancreas (Steiner, Newman et al. 2008, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012, Mawby, Whittemore et al. 2014, Dröes and Tappin 2017). Canine Pancreatitis Disorders originating from the liver and pancreas are considered important causes of morbidity and mortality in both dogs and cats, which presents different sets of challenges in diagnosis (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Dogs have several exocrine pancreas diseases including exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), pancreatic carcinoma, and pancreatitis (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Among them, pancreatitis is the most common disorder and are mostly considered idiopathic (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). Pancreatitis is the inflammation of the exocrine pancreas, wherein there is an infiltration with inflammatory cells. The term is usually expanded to include other diseases of the exocrine pancreas by necrosis or necrotising pancreatitis, or irreversible structural changes such as fibrosis (chronic pancreatitis) (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). The pancreatitis is in acute stage when there is neutrophilic inflammation while chronic is characterized by the acinar atrophy and fibrosis (Newman, Steiner et al. 2006, Watson, Roulois et al. 2007, Mansfield, Anderson et al. 2012 , Watson 2015, Dröes and Tappin 2017). https://i2.wp.com/thewholedog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/pancreatiitis.jpg?ssl=1 Fig. 01. An illustration of the difference of healthy pancreas vs. inflamed pancreas in dogs Despite being a common disorder in canines, the antemortem diagnosis of pancreatitis is clinically challenging (Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). Clinical signs are non-specific and varies greatly. Subclinical diseases are evident in most cases while others may display mild and non -specific clinical signs (Xenoulis 2015) which may include anorexia, vomiting, lethargy, diarrhea, melena, weight loss, hematemesis, and hematochezia (Hess, Saunders et al. 1998, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). Dogs with acute pancreatitis are at risk of developing obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocortcisim, hypothyroidism, prior gastrointestinal disease, and epilepsy (Cook, Breitschwerdt et al. 1993, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). On the other hand, cardiovascular shock,disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or multi-organ failure and death within hours of the development of clinical signs are presented in severe cases (Xenoulis 2015, Dröes and Tappin 2017). As diagnosis of pancreatitis remains a challenge, histopathology is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of pancreatitis. However, with procedural risks and difficulty to determine the right area for biopsy, obtaining the samples is hard (Newman, Steiner et al. 2004, Dröes and Tappin 2017). Therefore, considering the improving sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests, using a combination of different methods can be best used (Dröes and Tappin 2017). On the other hand, there are treatments for acute pancreatitis infected dogs. Treatments consider Intravenous Fluid Therapy, knowing that pancreatitis disturbs pancreatic microcirculation (Bassi, Kollias et al. 1994, Mansfield 2012). The administration of plasma is claimed to correct hypoalbuminemia, replacement of circulating α-macroglobulins, replacement of coagulation factors, and amelioration of systemic inflammation, however, no controlled studies on plasma transfusion in dogs with naturally occurring acute pancreatitis has proven its benefit (Mansfield 2012). Due to vomiting of infected dogs, anti-emetics are used to manage acute pancreatitis (Mansfield 2012). On the other hand, corticosteroids enhance apoptosis, and increase the production of pancreatitis-associated protein, giving protective effect against pancreatic inflammation (Zhang, Kandil et al. 2004, Mansfield 2012). Moreover, diet should also be managed including the treatment of the complications of the disease (Mansfield 2012) Canine Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity Assay Due to the limitations of the traditional golden standard, histopathology, diagnosis has relied on clinical criteria as an alternative gold standard (Graca, Messick et al. 2005, McCord, Morley et al. 2012, Cridge, MacLeod et al. 2018, Gori, Lippi et al. 2019, Nielsen, Holm et al. 2019, Okanishi, Nagata et al. 2019, Cridge, Mackin et al. 2020) and this includes measurement of cPLI (Cridge, Mackin et al. 2020). It has been proven over the decade that the PLI assay development, analytical validation, and evaluation is very useful for the diagnosis of pancreatitis in both dogs and cats (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012)( Xenoulis PG, Steiner JM, 2013). Pancreatic lipase is expressed exclusively by pancreatic acinar cells and thus plays an important role in assessing the exocrine pancreas (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Steiner, Rutz et al. 2006, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). The serum cPLI has been reported to detect specifically localized lipase in pancreatic acinar cells (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Dröes and Tappin 2017). This makes increase in serum PLI concentrations unlikely coming from the lipase of other tissues (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Considering the localization of the pancreatic lipase and the capacity of immunoassays to detect the unique protein structure of pancreatic lipase are known to be the advantages of measuring the serum cPLI during the diagnosis of exocrine pancreas diseases, resulting to high analytic specificity (Steiner,Rutz et al. 2006, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012) (Steiner JM, 2000; Hoffmann WE, 2008) (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011). Nowadays, diagnosis of canine pancreatitis has mostly considered serum cPLI assays as the most specific serum biomarkers (Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Mawby, Whittemore et al. 2014). However, the serum cPLI concentration doesn’t define the severity of pancreatitis (Steiner, Newman et al. 2008, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). References: Hoffmann WE. Diagnostic enzymology of domestic animals. In: Kaneko JJ, Harvey JW, Bruss ML, eds. Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Academic

Breed-related disease: Toyger cat

John K. Rosembert Lots of cats are named Tiger, but it wasn’t until Judy Sugden was struck by the two spots of tabby markings on the temple of her cat Millwood Sharp Shooter that it occurred to her that they could be the secret to developing a domestic cat that truly resembled the lord of the jungle. Starting with a striped domestic shorthair named Scrapmetal and a Bengal cat named Millwood Rumpled Spotskin, and later importing a street cat from Kashmir, India, who had spots instead of tabby lines between his ears, she went to work to create a tiger for the living room. Other breeders who shared her vision and contributed to the breeding program were Anthony Hutcherson and Alice McKee. They came up with a domestic cat that had a large, long body, tabby patterns and rosettes that stretched and branched out, and circular head markings. The International Cat Association began registering the Toyger in 1993, advanced it to new breed status in 2000, and granted the breed full championship recognition in 2007. Currently, TICA is the only association that recognizes the Toyger. oygers are instantly recognisable by their beautiful coat patterns. Their coats are dense and luxuriously soft, with a modified mackerel tabby pattern with branching and interweaving stripes. Brown mackerel tabby is currently the only recognised colour, giving these cats a black and gold striped look, much like a miniature tiger. The Toyger has a sleek, muscular body with a long, thick tail, which is carried low as well as small, rounded ears, and small to medium eyes, which are normally yellow or green. The friendly and playful Toyger likes people and other pets. He delights in playing fetch, batting around a feather or fishing-pole toy, and just spending time with family members. He’s active enough to learn tricks, but not so energetic that he’ll run you ragged. He has an easygoing personality that makes him suited to most households or families. The Toyger is generally a healthy cat and is no more predisposed to infectious diseases than any other breed. Some breeders claim that some cats show an adverse reaction to the feline leukaemia vaccine, but this has not been substantiated. Responsible breeders screen their cats against diseases to which Bengals can be prone, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKDef), and progressive retinal atrophy (PRA). However, anecdotal reports indicate that the incidence of all these conditions is significantly lower than in the Bengal, due to the Toyger’s outcross to domestic shorthairs. As they have dense, short hair, Toygers’ coats are very low maintenance, and only need to be brushed once a week. Sources: https://www.yourcat.co.uk/types-of-cats/toyger-cat-breed-information/ http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/toyger#health Photo credit : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyger

Breed-related disease: Dalmatians

John K. Rosembert Dalmatians are one of the oldest dog breeds known to man, although their exact origins are somewhat shrouded. The earliest recorded history of the breed places them in regions of Asia and Europe, particularly in Dalmatia, and it’s from here that the breed takes its name. Historically, Dalmatians have been known as coaching dogs, running around and beneath carriages, following their master’s travels. They are also known as the fireman’s friend, and once traveled along on runs in the days of the horse-pulled fire wagon. Dalmatians are a large, strong, muscular dog. The skull is about as wide as it is long, and flat on the top. The muzzle is about the same length as the top of the skull. The stop is moderate but well defined. The nose can be black, brown (liver), blue or a dark gray that looks like black. The teeth meet in a scissors bite. The medium-sized round eyes are brown, blue or a combination of both. The ears are set high, hanging down, gradually tapering to a rounded tip. The chest is deep. The base of the tail is level with the topline and tapers to the tip. The feet are round with arched toes. Toenails are white and/or black in black-spotted dogs and brown and/or white in liver-spotted dogs. The short coat has fine dense hairs. The symmetrical coat is predominantly white with clearly defined round spots. The spots can be black or brown (liver) which are the preferred colors in the show ring, but can also be, lemon, dark blue, tricolored, brindled, solid white or sable. Not all of these colors are accepted into the show ring, but they do occur in the breed. The more defined and well distributed the markings are, the more valued the dog is to the show ring. Puppies are born completely white and the spots develop later. They are highly energetic, playful and sensitive dogs. They are loyal to their family and good with children, although some Dalmatian experts caution that the breed may be too energetic for very small children. These dogs are intelligent, can be well trained and make good watchdogs. Some Dalmatians can be reserved with strangers and aggressive toward other dogs; others are timid if they are not well socialized, and yet others can be high-strung. These dogs are known for having especially good “memories” and are said to recall any mistreatment for years. Like other breeds, Dalmatians display a propensity towards certain health problems specific to their breed, Such as: Deafness A genetic predisposition for deafness is a serious health problem for Dalmatians; American Dalmatians exhibit a prevalence for bilateral congenital sensoneural deafness of 8%, (for which there is no possible treatment), compared with 5.3% for the UK population. Deafness was not recognized by early breeders, so the breed was thought to be unintelligent. Many breeders, when hearing testing started to become the norm, were amazed to discover that they had uni hearing dogs. Even after recognizing the problem as a genetic fault, breeders did not understand the dogs’ nature, and deafness in Dalmatians continues to be a frequent problem. Dalmatian-Pointer Backcross Project Hyperuricemia in Dalmatians (as in all breeds) is inherited, but unlike other breeds, the “normal” gene for a uric acid transporter that allows for uric acid to enter liver cells and be subsequently broken down is not present in the breed’s gene pool. Therefore, there is no possibility of eliminating hyperuricemia among pure-bred Dalmatians. The only possible solution to this problem must then be crossing Dalmatians with other breeds to reintroduce the “normal” uric acid transporter gene. This led to the foundation of the Dalmatian-Pointer Backcross Project, which aims to reintroduce the normal uric acid transporter gene into the Dalmatian breed. Hyperuricemia Dalmatians, like humans, can suffer from hyperuricemia, Dalmatians’ livers have trouble breaking down uric acid, which can build up in the blood serum (hyperuricemia) causing gout. Uric acid can also be excreted in high concentration into the urine, causing kidney stones and bladder stones. These conditions are most likely to occur in middle-aged males. Males over 10 are prone to kidney stones and should have their calcium intake reduced or be given preventive medication. Eye Problems Not many things have as dramatic an impact on your dog’s quality of life as the proper functioning of his eyes. Unfortunately, Dalmatians can inherit or develop a number of different eye conditions, some of which may cause blindness if not treated right away, and most of which can be extremely painful!. Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalmatian_(dog) https://www.dogbreedinfo.com/dalmatian.htm Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalmatian_(dog)

Breed-related disease: Burmilla

The Burmilla started out as an accident. In 1981, a Chinchilla Persian male and a Lilac Burmese bred, and the female delivered four kittens. These kittens had an unusual black-tipped coloring. The look of these cats was so attractive that a breeding program was inaugurated to produce a cat that would have the short hair of the Burmese, the roundness taken from both breeds, and the unusual coloring seen in the initial kittens. The Burmilla is rarely seen. In Britain, it is still an experimental breed, and it is not yet accepted by the major registries in the United States. The Burmilla is a medium-sized cat, but she is also stocky and heavy. This breed is somewhat compact while being very muscular with heavy boning. It is a cat that is very rounded. The head is round and the tips of the ears are round. The profile shows a “break,” and the eyes are very slightly slanted. The coat of the Burmilla is short and soft. Because of the original pairing, the coat is also thick and dense. The Burmilla is a fairly placid cat. She tends to be an easy cat to get along with, requiring minimal care. The Burmilla is affectionate and sweet and makes a good companion. They are good climbers and jumpers and should have cat trees and perches. The Burmilla is a sturdy, stocky cat and you might have to watch her weight carefully, particularly if she does not get enough exercise. Modify her nutrition if you need to do so. Burmilla’s are a typically healthy breed with an expected lifespan of 7–12 years. Therefore they are also prone to a few health issues, Such as: Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca causes dry eyes, chronic conjunctivitis and corneal vascularization Feline Orofacial pain syndrome affects male cats in particular, although females are also affected. Symptoms include exaggerated licking and chewing movements, plus excessive pawing at the mouth. This happens in distinct episodes, although the cat remains alert (albeit in distress) for the duration . The disease appears to be related to some kind of oral pain or distress, and is possibly linked to teething or dental disease. A possible risk factor is stress, but it is believed that there are also hereditary factors involved. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD ) an inherited kidney disease where cysts form in the kidneys at birth, gradually increasing in size as the cat ages. PKD eventually leads to kidney failure, however, it can be managed to help decrease the workload on the kidneys. Sources: https://www.petinsurance.com/healthzone/pet-breeds/cat-breeds/burmilla/ https://www.dailypaws.com/cats-kittens/cat-breeds/burmilla# : Photo credit: https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/cat-life-expectancy-burmilla

Breed-related disease: Basset Hound

Basset Hounds were originally bred in France and Belgium (“basset” is French for “low”). It is thought that the friars of the Abbey of St. Hubert were responsible for crossing strains of older French breeds to create a low-built scenting hound that could plod over rough terrain while followed on foot by a human hunting partner tracking rabbit and deer. Their accuracy and persistence on scent made Bassets a popular choice for French aristocrats, for whom hunting was a way of life. Bassets are very heavy-boned dogs with a large body on fairly short legs. Because they are bulky, bassets are slow maturing dogs, often not reaching full size until two years old. Bassets are immediately recognizable by their short, crooked legs, their long hanging ears and their large heads with hanging lips, sad expressive eyes, and wrinkled foreheads. The tail curves up and is carried somewhat gaily. The body is long and with the short legs gives bassets a rectangular appearance. The basset has a nice short, tight coat, with no long hair on legs or tail. Colors most commonly seen are tricolor or red and white but any hound color is acceptable. The Basset Hound is among the most good natured and easygoing of breeds. This breed is amiable with dogs, other pets, and children, although children must be cautioned not to put strain on this and all dogs’ backs with their games. The Basset is calm inside, but needs regular exercise in order to keep fit. They prefer to investigate slowly, and love to sniff and trail. These are talented and determined trackers, not easily dissuaded from their course. Because of this, they may get on a trail and follow it until becoming lost. This dog tends to be stubborn and slow moving. Bassets have a loud bay that they use when excited on the trail. Here, we summarized the most common health concerns you should look for over the lifetime of your Basset. Here we go: Bloat Gastric Dilatation and Volvulus, also known as GDV or Bloat, usually occurs in dogs with deep, narrow chests. This means your Basset is more at risk than other breeds. When a dog bloats, the stomach twists on itself and fills with gas. The twisting cuts off blood supply to the stomach, and sometimes the spleen. Left untreated, the disease is quickly fatal, sometimes in as little as 30 minutes. Your dog may retch or heave (but little or nothing comes out), act restless, have an enlarged abdomen, or lie in a prayer position (front feet down, rear end up). Back Problems Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) is a common condition in dogs with long backs and short legs, which may include your Basset. The disease is caused when the jelly-like cushion between one or more vertebrae slips or ruptures, causing the disc to press on the spinal cord. If your dog is suddenly unable or unwilling to jump up or go upstairs, is reluctant to move around, has a hunched back, cries out, or refuses to eat or go potty, he is likely in severe pain. He may even drag his back feet or be suddenly paralyzed and unable to get up or use his back legs. If you see symptoms, don’t wait. Call us or an emergency clinic immediately! For less severe cases, rest and medication may resolve the problem. Joint Disease When Basset puppies are allowed to grow too quickly, the cartilage in their joints may not attach to the bone properly. This problem is known as osteochondritis dissecans or OCD. If this occurs, surgery may be required to fix the problem. It’s best to stick to our recommended growth rate of no more than four pounds per week. Don’t overfeed him and don’t supplement with additional calcium. Feed a large-breed puppy diet rather than an adult or a regular puppy diet. Bleeding Tumor Hemangiosarcoma is a type of bleeding tumor that affects Basset Hounds at greater than average incidence. These tumors commonly form in the spleen, but can form in other organs as well. Unbeknownst to a pet owner, the tumor breaks open and internal bleeding occurs. Some tumors can be volleyball-sized or larger before signs of sickness show. We often find clues that one of these tumors is present during senior wellness testing, so have his blood tested and an ultrasound performed at least yearly. Sources: https://www.petfinder.com/dog-breeds/basset-hound/ https://coonrapidspethospital.com/client-resources/breed-info/basset-hound/ Photo credit: https://mom.com/momlife/19480-cool-facts-about-basset-hounds/

Pneumonia and gastritis in a cat caused by feline herpesvirus-1

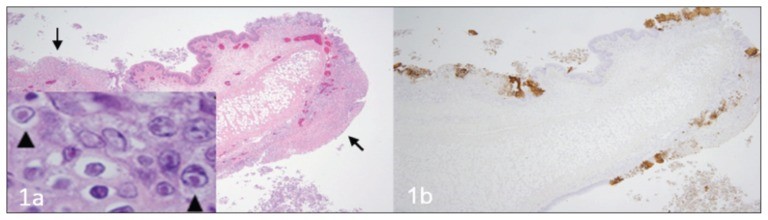

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712990/ A fatal respiratory and gastric herpesvirus infection in a vaccinated, 6-year-old neutered male domestic shorthair cat with no known immunosuppression or debilitation. Histology examination revealed severe necrotizing bronchopneumonia, fibrinonecrotic laryngotracheitis, and multifocal necrotizing gastritis associated with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies in affected tissues of larynx, trachea, lung and stomach. Immunohistochemistry also displayed strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in the corresponding section of larynx, trachea, lung and stomach. Figure 1 Larynx. Cat. a — Note the multifocal areas of ulceration (arrows) and inflammation. Inset: inclusion bodies (arrowheads) within epithelial cells adjacent to areas of ulceration. H&E. b — Immunohistochemistry of the corresponding section of larynx displaying strong multifocal immunoreactivity for FHV-1. Figure 2 Trachea. Cat. a — Note the denuded tracheal mucosa covered by a thick fibrinonecrotic exudate (asterisks), attenuation of the epithelium lining the tracheal glands (arrows) and numerous inflammatory cells infiltrating the tracheal wall. Inset: Inclusion bodies within the epithelial cells lining the tracheal glands (arrowheads). H&E. b — Strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in the epithelium of the trachea and tracheal glands. Figure 3 Lung. Cat. a — Severe neutrophilic necrotizing bronchopneumonia affecting airways (asterisks) and surrounding tissues. H&E. b — Strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. Figure 4 Stomach. Cat. a — Area of necrosis within the gastric mucosa (asterisk). H&E. b — Multifocal areas of FHV-1 immunoreactivity corresponding to areas of necrosis within the gastric mucosa.

Feline Tritrichomonas Foetus Infection: A Review

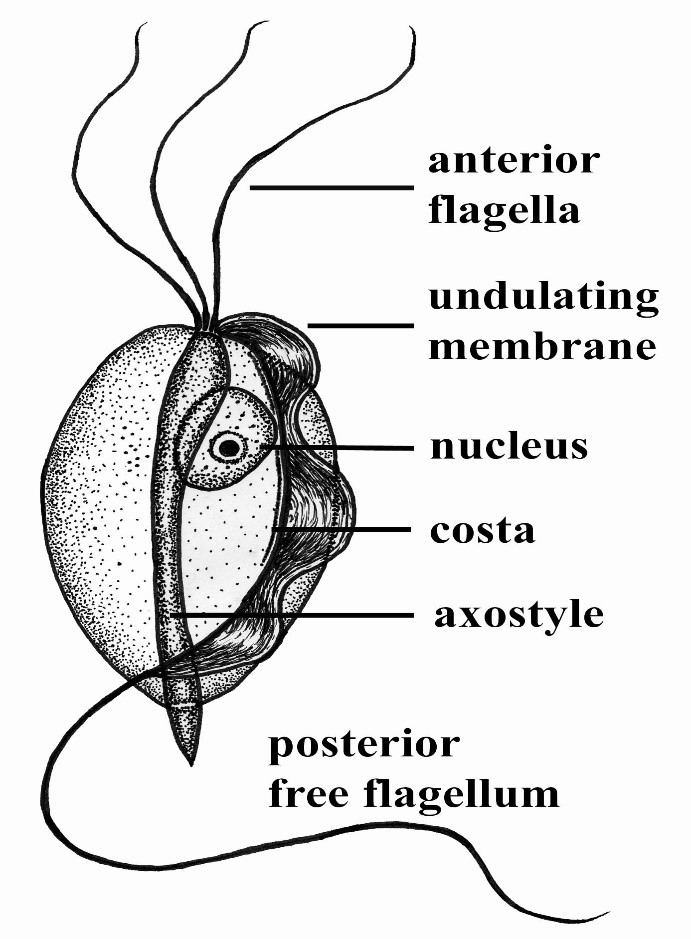

Maigan Espinili Maruquin Structure and Epidemiology The protozoan parasite Tritrichomonas foetus has sudden emergence of its syndrome in the 1990s causing feline intestinal tritrichomoniasis and has then attracted feline medicine studies (Levy, Gookin et al. 2003, Bell, Gowan et al. 2010) (Levy, Gookin et al. 2001 ). At a range of 10- 31%, infected cats in UK and USA comes from young, pedigree cats in multi-cat environment (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Gookin, Stebbins et al . 2004, Gunn-Moore, McCann et al. 2007, Frey, Schild et al. 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009)( Gunn-Moore D, Tennant B, 2007)(Bell, Gowan et al. 2010). An estimate 30% of purebred cats in USA are suggested infected by T. foetus (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Gookin, Stauffer et al. 2010). The T. foetus , like other trichomonads, has only trophozoite stage, however, it has a pseudocyst stage (Lipman NS, et. al., 1999) (Pereira-Neves, Ribeiro et al. 2003, Benchimol 2004, Mariante, Lopes et al. 2004, Yao and Köster 2015). Therefore, cats are presumed to be infected via direct contact due to the absence of the cyst stage (Zajac AM, Conboy GA, 2006). The parasite is pear- or spindle-shaped, having three anterior flagella and one posterior flagellum. With its size of approximately 10-25 μm in length and 3-15 μm in width, the undulating membrane extends along the whole length of the body which emerges as the posterior flagellum. This trophozoite reproduces asexually by longitudinal binary fission (Yao and Köster 2015). (https://www.k-state.edu/parasitology/625tutorials/Protozoa10.html) Fig. 01. Morphologic structure of the Tritrichomonas foetus Infected cats were reported to experience chronic large bowel diarrhea as the parasite was found in the feline intestine (Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Payne and Artzer 2009). Reports also showed the presence of the organism in the feline uterus (Dahlgren, Gjerde et al. 2007). Further, the isolates of T. foetus from cattle are known to be infectious for the cats, while the isolates of the same species from cats are infectious to cattle (Stockdale, Dillon et al. 2008, Walden, Rodning et al. 2008, Payne and Artzer 2009). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis Despite suggestions of strong association of feline T. foetus and chronic diarrhea (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Mardell and Sparkes 2006, Gunn-Moore, McCann et al. 2007, Burgener, Frey et al. 2009, Holliday, Deni et al. 2009, Pham 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009, Kuehner, Marks et al. 2011), whether the parasite alone is sufficient to cause clinical signs or the foetus-associated diarrhea, being a primarily multifactorial disease involves concurrent infection with other enteropathogens, host and environmental factors (Gookin, JL, et. al., 1999) (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Bissett, Gowan et al. 2008, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009, Kuehner, Marks et al. 2011). It is possible that the trophozoites are transmitted by a fecal- oral route from an infected to uninfected cat (Yao and Köster 2015). Symptoms may appear early as 2 to 7 days after orogastric inoculation (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015). Whereas, infected cats showed anorexia, depression, vomiting and weight loss while experimental infections also reported vomiting and fever (Mardell and Sparkes 2006, Xenoulis, Lopinski et al. 2013, Yao and Köster 2015)( Stockdale, H., et al., 2007). Chronic large bowel diarrhea, associated with blood, mucus, flatulence, tenesmus, and anal irritation were also reported (Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Payne and Artzer 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009). With the characteristic of the trichomonads as commensal organisms, some hosts show no clinical signs and are asymptomatic (Payne and Artzer 2009). In some studies, the parasite, with its surface located antigen, was detected on epithelial surface and within the superficial detritus of the cecal and colonic mucosa (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015), while naturally infected cats showed parasite in close proximity to the mucosal surface and less frequently in the lumen of colonic crypts (Yaeger and Gookin 2005, Yao and Köster 2015). Conclusively, T. foetus trophozoites can be detected in epithelial surface and crypts of cecum and colon (Yao and Köster 2015). Mechanisms were then described to include possibilities of alterations in the normal intestinal flora, adherence to the epithelium, and elaboration of cytokines and enzymes (Payne and Artzer 2009). Diagnosis For cats <6months old with recent clinical signs of chronic large bowel diarrhea, infection with T. foetus infection is suspected (Yao and Köster 2015). Diagnosis of the T. foetus infection may be conducted via direct observation of the flagellates in fresh or cultured feces (Payne and Artzer 2009) or on a saline diluted direct fecal smear (Yao and Köster 2015). The trophozoites of T. foetus are difficult to distinguish from Giardia spp and other nonpathogenic intestinal trichomonads. However, although the size of T. foetus and Giardia spp are almost the same, they move differently. The movement of Giardia spp. resembles the fall of a leaf while trichomonads move erratically (Yao and Köster 2015)( Gookin JL, Levy MG, 2008). Feline feces can be cultivated and be tested in commercially available InPouch™ TF medium (Payne and Artzer 2009, Yao and Köster 2015) or DNA extraction and amplification of T. foetus rDNA by the use of PCR from feces samples can be conducted (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Manning 2010, Yao and Köster 2015). Moreover, other causes of diarrhea, like bacterial, viral, other parasites, and nutritional problems should be ruled out before a diagnosis of tritrichomoniasis can be made (Payne and Artzer 2009). Treatment and Disease Managements The T. foetus infection in cats has no approved treatment. While treating infected animals is difficult, success is also limited (Payne and Artzer 2009). Literatures have used therapeutics including paromomycin, fenbendazole, furazolidone, nitazoxanide, metronidazole, tinidazole and ronidazole (Gookin, Breitschwerdt et al. 1999, Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015). The ronidazole is not registered for human or veterinary use (Yao and Köster 2015) however, it showed effectiveness in experimentally infected cats (Gookin, Copple et al. 2006) (Gookin JL, Dybas D, 2008). Due to possible neurologic side effects, caution is observed

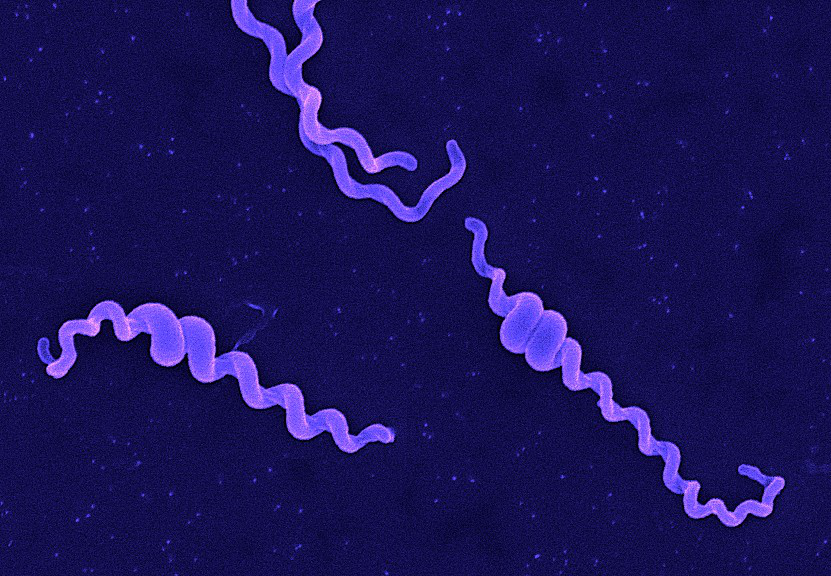

Leptospirosis

Andy Hua Introduction Classification Taxonomy Classically, the genus Leptospira was divided into 2 species based on genetic analysis: L. interrogans sensu latu (pathogenic strains) and L. biflexa sensu latu (saprophytic strains). L. interrogans is divided into more than 250 serovars based on antigenic composition and further classified into antigenically related serogroups. There is a serovar spectrum and frequency that differs according to countries and regions (depending on distribution of rodent hosts, import of dogs from abroad, use of vaccination). The main infecting serovars in dogs were Icterohaemorrhagiae and Canicola in Europe and America prior to 1960. Since the use of the bivalent vaccine against Canicola and icterohaemorrhagiae , OTHER serovars A to the Shift occurred .Besides. L. icterohaemorrhagiae and L. canicola , serovars Importance of Dogs in the include: grippotyphosa , Bratislava , Saxkoebing , Sejroe , Copenhagi , Australis , Bataviae , and Pomona , autumnalis , and hardjo . Icterohaemorrhagiae and Canicola infections in unvaccinated dogs still occur, indicating that these serovars are not fully eradicated. Leptospires are motile, obligate aerobe, gram-negative bacteria, which are not visible in routinely fixed smears. Dark field microscopy (Fig. 1) or phase contrast microscopy is necessary for visibility of unstained leptospires. Clinical Effects Epidemiology Habitat Leptospires have been isolated from birds, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates. Rodents and wild carnivores are the most frequent carriers. Reservoir hosts show few or no signs of disease. Leptospira spp. are commonly sequestered in the renal tubules of mammalian kidneys. Different serovars typically have different reservoir hosts. Lifecycle Generation time in culture media or host is long. Transmission Direct or indirect transmissions are possible. Indirect transmission through contaminated water or soil is more common. Pathological effects Infection occurs through ingestion of infected rodents or penetration of mucosae or traumatized skin. Leptospiremia occurs within 1 week. Leptospires spread to other organ systems (kidneys, liver, spleen, endothelial cells, lungs, uvea/retina, skeletal and heart muscles, pancreas, and genital tract) and cause tissue damage, visceral and vascular inflammation. Leptospiral pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome (LPHS) Lung: pulmonary hemorrhage can occur as severe manifestation of acute leptospirosis. Leptospires can persist in immune privileged site (eg, renal tubes, eye). In the presence of adequate antibody titers, leptospires are eliminated from most organs. In the presence of low antibody titers mild leptospiremia can continue with a subclinical course of disease. Other Host Effects Individual host may show little or no clinical signs but may be source of infection in the same animal species. An animal that has recovered may become a long-term shedder of the organism. Mainly dogs show disease, rodents often the reservoir. Cat disease is uncommon, but serology shows that asymptomatic infection occurs. Individual host can show little or no clinical signs but can be source of infection to other animals or humans. An animal that has recovered can become a long-term shedder of the organism. Rodents are often the reservoir. Dogs commonly succumb to disease if infected. In cats, disease is uncommon but asymptomatic infection and shedding in urine occurs. Control Control via animal Antimicrobial therapy Dogs with gastrointestinal signs should initially be treated with intravenous penicillin derivates (eg, ampicillin or amoxicillin 20-30 mg/kg q6-8h). These should be continued until gastrointestinal signs are under control and liver enzymes are normalized. A directly following antimicrobial therapy with 3 weeks of oral doxycycline (5 mg/kg q12h) is necessary for prevention of carrier states. Dogs without gastrointestinal signs should immediately be treated with doxycycline. Antibody testing of dogs living in the same household as infected dogs is recommended. Oral doxycycline (5 mg/kg q12h for 3 weeks) should be administered, if these dogs have antibodies. Symptomatic treatment Treatment of dogs with gastrointestinal sings includes antiemetics, gastroprotectants, and nutritional support. Use of opioids in dogs with pain can be necessary. Treatment of dogs with acute kidney injury (AKI) includes correction of loss of fluid, electrolytes, acid-base imbalances and hypertension, and if necessary hemodialysis for patients with persistent oligoanuria, life-threatening hyperkalemia, or severe volume overload. Oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation can be necessary in dogs with LPHS. Plasma transfusions can be necessary for patients with DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation). Whole blood transfusion can be helpful, if bleeding occurs. Hemodialysis Hemodialysis is necessary in dogs with acute renal failure (life-threatening hyperkalemia or severe volume overload) and in dogs with advanced uremia refractory to medical management. Early referral to facilities where hemodialysis is available is recommended. Renal recovery usually occurs after 2-7 days of dialytic support. Hemodialysis leads to favourable prognosis for renal recovery (in more than 80% of dogs). Mechanical ventilation Anesthesia ventilators: overview can be necessary in dogs with severe pulmonary hemorrhage due to LPHS. Vaccination Vaccination protects against clinical disease and carrier status with shedding. Protection is serogroup-specific and temporary. Annual boosters are required. Diagnosis Leptospirosis at its onset is often misdiagnosed as aseptic meningitis, influenza, hepatic disease or fever (pyrexia) of unknown origin. Despite being common, the diagnosis of leptospirosis is often not made unless a patient presents with textbook manifestations of the so called Weil’s disease, such as fever plus jaundice, renal failure and pulmonary haemorrhage. Leptospiral infection often has minimal or no clinical manifestations; of the cases in which fever develops, as many as 90% are undifferentiated febrile illnesses. Moreover, clinicians may fail to recognize that transmission of leptospirosis can occur in the urban setting because it is incorrectly perceived to be a rural disease. Therefore, diagnosis is based on laboratory tests rather than on clinical symptoms alone. In developing countries,Laboratory facilities may be inadequate for diagnosis a high prevalence of the disease. Of substantial clinical importance despite the syndrome of leptospiral pulmonary haemorrhage has emerged in recent years, in diverse places around the world. Two important issues continue to confront clinicians regarding leptospirosis. The first is how to reliably establish the diagnosis. The most common way to diagnose leptospirosis is through serological tests either the Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT) which detects serovar-specific antibodies, or a solid- phase assay for the detection of Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. Leptospira are present in the blood until they are