Canine Distemper Virus

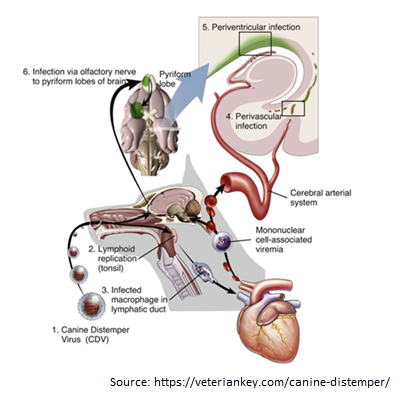

Canine Distemper Virus Tang Nguyen Mai Trinh Infection of canine distemper virus (CDV) is common in most terrestrial carnivores in the wild, especially in the Canidae family (eg, wolves, foxes, domestic dogs, etc.), as well as certain ferrets, otters, raccoons, cats, and even marine animals [1]. CDV is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family which the genus Morbilivirus was first described in the 1970s, however, it was only isolated in 1905 from the nasal secretions of infected dogs by a French veterinarian, [2]. CDV is now known as the most dangerous disease in dogs because of its propensity to infect through respiratory and digestive pathways and cause death in virtually all canines. When infected with it, the unvaccinated host has a 100% mortality rate [3]. Structure of Canine distemper virus CDV is known as a single-stranded RNA virus, like many other viruses CDV has an N nucleocapsid protein that is responsible for genome replication, matrix (M), fusion (F), phosphoprotein (P), and polymerase (L) which are involved in genomic and mRNA transcription. Whereas nonstructural proteins C and V have been identified as virulence factors involved in the modulation of immune responses and innate immunity, proteins like H and F are essential for viral attachment, invasion, and fusion into host cells [4-6]. Transmission Puppies and dogs most often become infected through airborne exposure to the virus from an infected dog or wild animal. CDV enter the dog’s body through respiratory secretions, most notably coughing and sneezing. Virus particles can spread about 25 feet with a single sneeze, then proliferate in immune cells such as macrophages, T and B cells via the SLAM receptor within 24 hours [8] and spreads to tonsils and lymph nodes via the lymphatic vessels, causing long-term immunosuppression [9-11]. The amount of virus in the lymph nodes of the throat, tonsils, and bronchi will go up after 2 to 4 days of infection, and the virus continues to release and replicate in multiple organs. This process takes 4 to 6 days after infection and affects organs such as the thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, stomach cells, lungs, and bone marrow. The increased concentration of virus in the lymph node tissue at this time causes the number of white blood cells to decrease, resulting in the infected dog’s body temperature increasing [12]. The virus begins to migrate to specific epithelium and the central nervous system (CNS) via the blood or CSF after around 8 –10 days [10]. Simultaneously, organs such as the respiratory tract, intestines, and urinary tract begin to experience significant infections as lymphocytes are destroyed, resulting in a massive release of viruses into these organs [13]. Figure 2. The process of entry and replication of CDV in dogs.1, The CDV virus enters the dog’s body through the respiratory tract. 2, the virus begins to multiply in the tonsils, bronchial lymph nodes, oropharyngeal nodes, and gastrointestinal lymphoid tissues. 3, the virus attacks immune cells such as macrophages and is released to other organs such as the heart. 4, The virus enters the central nervous system (CNS) through the circulatory system. 5, Virus enters the cerebrospinal fluid (CFS). 6, Viral migration to the pyramidal lobes of the cerebral cortex through the nasal passages to the central nervous system [14]. Clinical Symptoms of Canine Distemper Virus infection in dogs The CDV virus can cause disease in dogs of any age, although it is more common in pups aged 12 to 16 weeks and in unvaccinated dogs. Because pups’ immune systems are so immature, they are easily infected by the virus if they come into touch with dogs that have already been afflicted with CDV. When the dog get infected with the CDV virus, early symptoms include fever, weariness, lack of appetite, apathy, and a reluctance to be active [9]. However, these symptoms are quite similar to those of the parvovirus, which primarily infects the digestive system, whereas CDV not only assaults the digestive system but also damage to the respiratory system, neurological system, bones, arthritis, eyes, and skin [13]. Prolonged vomiting, diarrhea, severe dehydration, and stool abnormalities in color, consistency, and blood and mucus contribute to gastritis and intestinal inflammation in the early stages. Finally, the dog was unable to defecate, resulting in death (Figure 3A). Pus discharge, ulcers, and progressively becoming clouded eyes can lead to conjunctivitis and even blindness, while the skin appears as spots with pus within, then gradually changes from red to yellow (Figures 3 B and C). Signs such as a runny nose with green mucus in the early stage, shortness of breath in the latter stage, and shortness of breath lead to pneumonia in the respiratory system (Figure 3B). Figure 3. Signs of CDV infection in dogs. A, Dogs have digestive system damage, diarrhea with blood [17]. B, Eyes are damaged causing pus discharge, ulcers, while the nose shows signs of runny nose with green mucus [15]. C, The skin also appears spots that have pus inside. D and E, the dog’s paw and nose epithelium show basal keratinocytes. F, enamel deterioration in adult dogs following neonatal CDV infection [13]. When the disease is severe, evidence of central nervous system damage such as convulsions, hemiplegia, or quadriplegia will occur; at this stage, 99% of infected dogs will die. Furthermore, the CDV virus can attach to lymphocytes and enter the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), causing harm to the central nervous system. In addition, CDV was discovered in the foot and nasal epithelium, promoting basal keratinocyte growth, which was clearly recognized in the Figures 3D and E. Although CDV infection leads to the above clinical signs, however the appearance of these signs is also dependent on habitat, age, host immunity, and virulence of the virus strain [13]. Studies have also demonstrated that CDV can be passed from mother to puppy through the placenta during pregnancy. When the mother dog is infected with the virus, it can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, but this depends on the pregnancy stage of the mother dog [16]. For the lucky puppies

Canine Babesiosis

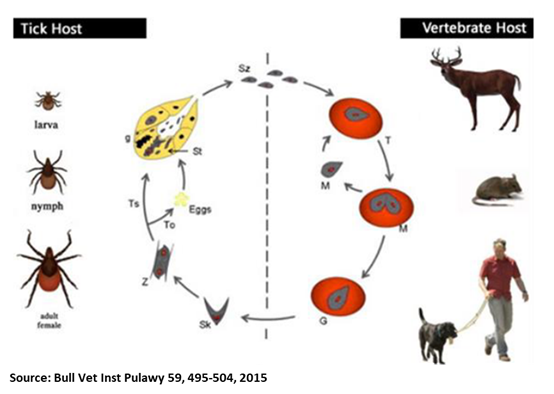

Oliver Organista, LA Canine babesiosis is a tick-borne, protozoal, haemoparasitic disease that can cause varying degrees of haemolytic anaemia, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia and fever. It is very endemic to different parts of the world, and presents varying clinical, hematological, and pathological manifestation depending on the species and subspecies involved.1,2 There are two hosts for the transmission of Babesia spp., viz. invertebrate (tick) and vertebrate host. Dogs are one among the many targets of Babesia spp., causing canine babesiosis, and now there are clinical evidences of possible vertical transmission too. Dogs of all ages can be affected with Babesia spp., but young puppies are more commonly affected. Two Babesia parasites were thought to occur in dogs; the relatively large intra-erythrocytic piroplasm referred to as Babesia canis and a smaller parasite, known predominantly as the cause of canine babesiosis in Asia, Babesia gibsoni. B. canis has been reclassified into three separate species (B. canis, B. rosi, B. vogeli) on the basis of immunity, serological testing, vector specificity and molecular phylogeny At least 4 genetically and clinically distinct small piroplasms affect dogs which include: Babesia gibsoni–originally described in India nearly a century ago and now occurring sporadically in other parts of the world including the Australia; Babesia conradae, a piroplasm that occasionally infects dogs in California; Theileria annae, a Babesia microti-like parasite that has so far been reported only in northwest Spain, transmitted by Ixodes hexagonus ; and a fourth small piroplasm, B. (=T.) equi has also been reported in dogs in Spain.³ Prevalence of Babesiosis The incidence of canine babesiosis vary considerably from one country to another depending on the distribution of the causative parasite and their specific vectors. Table below shows the data gathered during the Questionnaire-based survey on the distribution and incidence of canine babesiosis in countries of Western Europe.5 DIAGNOSIS, SYMPTOMS, AND TREATMENT Diagnosis. In the past, babesiosis was diagnosed by seeing the parasite on a blood smear. Other diagnostic tests are becoming more readily available, including FA (fluorescent antibody) staining of the organism and ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) tests. A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is also available and is commonly used to diagnose babesiosis. The PCR test has the advantage in that it can detect all four species of Babesia. Serologic or antibody titer testing in the diagnosis of babesiosis has limitations. A positive test result is dependent on an antibody response by the infected dog, which may take up to ten days to develop. Once a dog has developed antibodies to babesiosis, they may persist for years and this must be considered when performing follow-up tests.6 Symptoms. Dogs typically present with the acute, severe form of babesiosis, which is characterized by findings such as abnormally dark urine, fever, weakness, pale mucous membranes, depression, swollen lymph nodes, and an enlarged spleen. Potential complications: Bleeding problems, a severe type of anemia that leads to jaundice, organ damage, death.7 Treatment. The FDA approved treatment for babesiosis is imidocarb diproprionate. A combination therapy of quinine, azithromycin, atovaquone, and/or clindamycin is being researched and may become more common to treat dogs within the US or Canada in the future. Clindamycin, the treatment of choice for Babesia microti, the main Babesia species that infects humans, can also be used against Babesia in dogs. Clindamycin is a readily available antibiotic and is an excellent starting point for treatment in many dogs. Your veterinarian will discuss any alternative and adjunctive treatments with you.7 TRANSMISSION AND PREVENTION OF BABESIOSIS How is dog Babesia transmitted? Transmission. In most cases, Babesia organisms are spread to dogs through the bite of an infected tick but is not likely to be transmitted until a tick is attached for 36 hours. However, some studies suggest that infected dogs with open mouth sores can pass on the infection to other dogs through a bite, and infected pregnant females can transmit babesiosis to their unborn puppies. It can also be transmitted by the needle passage of infected blood, inadvertently in the case of blood transfusion or deliberately during experimental studies. Generic Life Cycle of Babesia spp.10 Generic life cycle of Babesia spp. Sporozoites (Sz) are injected into a vertebrate host blood system, during the blood meal of an infected tick. After invasion, Sz differentiate into trophozoites (T). Trophozoites undergo asexual division into two or four merozoites (M) in the infected red blood cells. Merozoites exit the red blood cells and invade new ones. Some groups of merozoites transform into gamonts or pregamotyces (G). The process of gamogony and sporogony takes place in the tick. Gamonts ingested by a tick feeding on an infected host differentiate in the gut into gametes (called ray bodies or Strahlenkorper – (Sk)) that fuse forming a diploid zygote (Z, gamogony). Via meiosis division, zygotes give rise to motile haploid kinetes. After haploid kinetes multiply by sporogony, they penetrate the tick haemolymph and organs. The final stage of the development occurs in the salivary glands (Sg), where differentiation and multiplication occur. Kinetes transform into sporozoites that infect the vertebrate host after vector development into a subsequent life stage – larvae to nymph, nymph to adult (transstadial transmission, Ts). In large Babesia spp. kinetes also invade the tick ovaries and eggs, and infective sporozoites are formed in the salivary glands of the next generation larvae. This process is called transovarial transmission (To). Adopted and reproducted from Schnittger et al. 9 How ticks spread disease11 Ticks transmit pathogens that cause disease through the process of feeding. Depending on the tick species and its stage of life, preparing to feed can take from 10 minutes to 2 hours. When the tick finds a feeding spot, it grasps the skin and cuts into the surface. The tick then inserts its feeding tube. Many species also secrete a cement-like substance that keeps them firmly attached during the meal. The feeding tube can have barbs which help keep the tick in place. Ticks also can secrete small amounts of saliva with anesthetic properties so that the animal or person can’t feel that the tick has attached itself. If the tick is in a sheltered spot, it can go unnoticed. A tick will suck the blood slowly for several days. If the host animal has a bloodborne infection, the tick will ingest the pathogens with the blood. Small amounts of saliva from

Thyroid Function in Animals

Sushant Sadotra Introduction: The thyroid is one of the endocrine glands in vertebrates. The thyroid gland has a bilobed structure located below the larynx and overlays the trachea in animals. In different animals, Anatomical variations of the thyroid are primarily seen in the isthmus connecting the gland’s two lobes. The size of the gland approximates 0.20% of body weight. However, the size may increase due to iodine deficiency, ingestion of goitrogenic toxins, tumors, and hyperactivity of the gland, or maybe reduced to fibrotic due to hyperthyroidism. Thyroid follicles are the thyroid gland’s functional units with a spherical structure composed of an inner core of the thyroglobulin-hormone complex, colloid. The colloid is surrounded by an outer monolayer of follicular cells and acts as the storage tank of thyroid hormone. The overall size of the follicles and the shape of their follicular cells may differ due to the functional activity of the thyroid gland. The dormant follicular cells are squamous-shaped compared to the tall columnar, highly active follicular cells. Other than colloid, the thyroid C-cells are interspersed between the follicles. The thyroid C-cells are the source of the hypocalcemic hormone calcitonin that is associated with calcium metabolism. The third type of tissue embedded in the thyroid gland is the parathyroid. The parathyroid is the source of the hypercalcemic hormone parathormone. Functions of the thyroid gland: The thyroid gland functions the same in all animals. There are four primary functions of the thyroid gland in animals; trapping the iodide, synthesis of thyroid hormones, storage, and release of hormones. All these activities of the thyroid gland are usually regulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a pituitary hormone. Hormonogenesis and release of thyroid hormone mainly have four stages: Trapping of Iodide: The follicular cells trap the circulating I– from the blood against the concentration gradient mediated by a sodium iodide symporter (NIS) protein present on the thyroid follicular cell membrane. A trapping enzyme catalyzes the trapping process via a mode of active transport catalyzed by an ATP-dependent Na+K+-ATPase. This trapping system’s high efficiency can concentrate most blood iodine in the thyroid gland. This process is stimulated by TSH and blocked by large amounts of I– or goitrogenic agents. (Figure 1) Synthesis of Thyroid Hormones: The trapping of I- is followed by its oxidation, catalyzed by peroxidase to form a highly active free radical I*. This reaction is also stimulated by TSH and inhibited by thyrotoxic agents (thiouracils or thioureas). At the follicular cell membrane-colloid interface, highly active I* binds to thyroglobulin, a thyroidal glycoprotein of a high molecular weight of 660 kDa. I* binds to thyroglobulin at its tyrosine moieties to form monoiodotyrosine (MIT) or a diiodotyrosine (DIT). After that, the iodinated phenyl groups of the tyrosine undergo oxidative condensation resulting in the synthesis of thyroid hormones. The thyroid gland produces two active hormones: 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine (T3) and 3,5,3′,5,-tetraiodothyronine (T4). T3 is formed by the oxidative condensation of an iodinated phenyl group of one DIT to an MIT group or of one DIT to another DIT to create T4. The inner deiodination product of the T4 is the inactive hormone is 3,3′,5’-triiodothyronine (rT3). Storage of hormones: Thyroid follicular cells synthesized thyroglobulin and localized it to the cell membrane for the iodination process. Iodinated thyroglobulin, also known as a colloid, is released and stored in the lumen of the follicle. Release of hormone: TSH stimulates the release process of hormones. TSH acts at the follicular cell membrane, the second site of action for TSH. Colloid from the lumen is taken up to the follicular membrane, where they are taken in as vesicles into the follicular cells by the process of endocytosis. Lysosomes merge with these vesicles to release lysosomal proteases that hydrolyze the colloid. Hydrolyses of colloid release their T3, T4, DIT, and MIT. Microsomal tyrosine deiodinases enzymatically degrade the released DIT and MIT, and their iodine is recycled within the follicular cell. A simple diffusion process releases the T4 and T3 into circulation. Out of the total hormone released from the gland, 90% is T4, and only 10% is T3. The phenyl group of T4 may also undergo some deiodination within the gland or in the peripheral tissues to form rT3. rT3 is an inactive form of the T3 hormone. Therefore it undergoes a degradation pathway. (Figure 1) The regulation of T3 and T4 secretion starts in the hypothalamus. The thyrotropin-releasing hormone secreted from the hypothalamus acts on the pituitary gland. This stimulates TSH secretion, which ultimately acts on the thyroid gland, producing and releasing thyroid hormones. The action and disorder of Thyroid Hormones: In humans and animals, thyroid hormones play a vital role in regulating metabolic and cellular mechanisms. The mode of action can be quick in minutes or prolonged to hours or longer. Thyroid hormones in normal levels work together with other hormones like insulin (beta cells of the pancreatic islets) and growth hormone (pituitary gland) to work on protein synthesis in different cellular processes. However, thyroid hormones can be catabolic in excess (hyperthyroidism), with increased protein breakdown and gluconeogenesis. Hyperthyroidism is more common in cats middle-aged to old cats than in dogs. However, thyroid carcinoma could be a cause when it occurs in dogs. Decreased levels of thyroid hormones (hypothyroidism) cause a slower metabolic rate in animals. This disorder is most likely seen in middle-aged (4-10 Years) dogs and mid to large-size dog breeds (Doberman pinscher, Golden retriever, etc.). Also, spayed female dogs have a higher hypothyroidism risk than unspayed ones. On the contrary, naturally occurring hypothyroidism is rare in cats. Reference: Kaneko, J. J. (2008). Clinical biochemistry of domestic animals. San Diego: Academic Press. Thanas C, Ziros PG, Chartoumpekis DV, Renaud CO, Sykiotis GP. The Keap1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in the Thyroid—2020 Update. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(11):1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9111082 Mark E. Peterson. The Thyroid Gland in Animals. Last full review/revision Jul 2019 | Content last modified Oct 2020. MSD MANUAL Veterinary Manual, https://www.msdvetmanual.com/endocrine-system/the-thyroid-gland/the-thyroid-gland-in-animals

Breed- Related Diseases: Boxer

The Boxer breed was originally used to hunt large game and in fighting or baiting. However, the Boxers today are more refined and elegant than their ancestors, but they are still strong, smart, and fearless. This breed has smooth coat. With its medium size, it has square build and strong bone, with stretched muscles and strongly developed and molded appearance. The Boxers are a friendly and high-spirited breed, who are patient and gentle with children. They are fun, can play willingly, and are of high-energy dogs. They enjoy close human contact and is known as one of most popular dogs in America. However, this dog can be rowdy, gassy and drool a lot, attention- seeker which may exhibit signs of separation anxiety if left alone too much, and could be suspicious of strangers. On the other hand, like other dog breeds, Boxers can suffer from several health issues. Some of them can be treated if diagnosed early enough, and thus visiting your veterinarian to perform yearly tests and talk over health issues of your companion is important. Cancer– It is the most common health issue with this breed. It can be brain, thyroid, mammary glands, testes, heart, spleen, blood, lymph system (lymphoma), and other organs. Catching this early greatly increases the odds of survival, thus owners should keep an eye out for early symptoms. White Boxers, and colored Boxers with white markings are vulnerable to develop skin cancer from sunburns. Cardiomyopathy– This condition affects the heart muscle tissue which may result in episodes of weakness, fainting and sudden cardiac death, while some patients can develop congestive heart failure. This shows an irregular heartbeat. Aortic stenosis– A condition wherein there is a narrowing of the valve through which blood leaves the heart, usually caused by a fibrous ring of tissue. This may lead to progressive damage to the chamber that pumps the blood out of the heart, making the organ work harder to do its job. Regular health checks can help your vet detect the presence of this condition. A veterinary cardiologist can typically diagnose this condition after a heart murmur has been detected. Breeding dogs with this condition should be avoided. Bone and Joint Problems– These include hip dysplasia, cranial cruciate ligament ruptures (in the knee joints) and degenerative myelopathy (a progressive disease affecting the spine). Each condition can be diagnosed and treated to prevent undue pain and suffering. In the preventive healthcare of musculoskeletal disorders, keeping the right weight, providing high-quality diet, and avoiding and avoid excessive work on the knees (like playing Frisbee) are key in avoiding this painful injury. Also, joint supplements can be provided. Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV) or Bloat or Torsion– This life- threatening condition occurs when air, fluid, food or foam collects in the stomach and making it expand, with or without twisting of the stomach. Whereas, stomach twisting can trap contents which leads to restricted blood flow to organs such as heart and stomach. Bloat may be suspected if your Boxer started to show swollen upper abdomen, signs of anxiety or agitation, retching but unable to vomit, excessive drooling or panting, and may be restless, depressed, lethargic, and weak with a rapid heart rate. Degenerative Myelopathy (DM)– It is a neurological disease reported in Boxers after middle age, and despite being not common, the Boxer is among the top 3 breeds to develop this. It affects the spinal column and nerves that coordinate the movement of the rear legs. This leads to paralysis, then progresses to front legs. Affected Boxers eventually lose their ability to walk, incontinent and are euthanized. This is a progressive, incurable disease of the spinal cord. Despite not being painful, it is quite serious. Allergies– Watch out for itchy, scaly skin, the breed Boxers are prone to allergies, both environmental allergies and food-related allergies. It is important to provide a proper diet and exercise routine to your Boxer. Keeping an appropriate weight is the easiest way to improve his health and extend his life. Building a routine care will help your Boxer live longer, stay healthier, and be happier during her lifetime. Any abnormal symptom could be a sign of serious disease, know when to seek veterinary help, and how urgently. References: https://animalhealthcenternh.com/client-resources/breed-info/boxer/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/boxer#health https://www.animalfriends.co.uk/dog/dog-advice/dog-breed-health-problems/boxer-health-problems/ https://www.usboxer.org/health-issues http://www.allboxerinfo.com/boxer-dog-health-problems https://pavg.net/news/common-diseases-in-boxers/

Hyperthyroidism is not a risk factor for subclinical bacteriuria in cats: A prospective cohort study

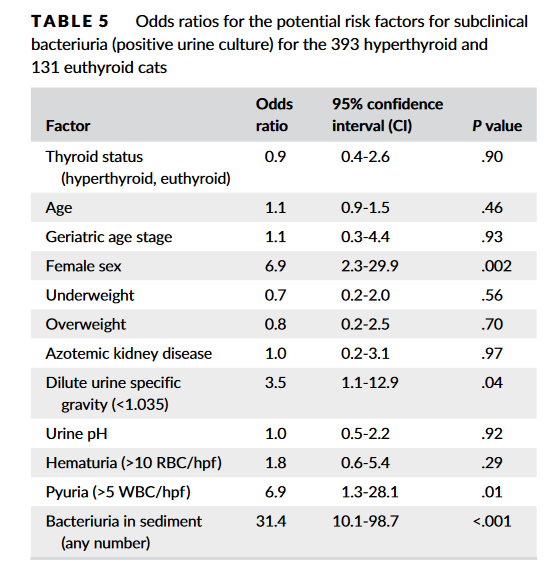

Source: https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15769 Subclinical bacteriuria is the presence of bacteria in urine with no clinical evidence of urinary tract infection (UTI). Some previous studies indicated that hyperthyroid cats are susceptible to UTIs (mostly subclinical) with prevalence rates of 12%-22%. As a result, many clinicians would recommend urine culture when evaluating hyperthyroid cats. To determine the true prevalence of subclinical bacteriuria in cats with hyperthyroidismIn, Eeterson M.E.’s group conducted a prospective cohort study. Both hyperthyroid and euthyroid cats had urine collected by cystocentesis for complete urinalysis and culture. Data pertaining to age, sex, body condition, and serum thyroxine and creatinine concentrations also were acquired. Hyperthyroid cats showed a low prevalence of subclinical bacteriuria (4.3%), which did not differ from that found in euthyroid cats (4.6%) in this study. In addition, only female sex was a significant risk factor. In conclusion, hyperthyroid cats are not at risk for subclinical bacteriuria.

Alaskan Malamute Guide: Health, Care, and Genetic Screening

Table of Contents 1. Introduction Overview of the Alaskan Malamute Breed The Alaskan Malamute is a powerful, heavy-duty spitz-type dog, historically bred as a freight-carrying sled dog in the Arctic. Its name derives from the Mahlemut Inuit tribe, who developed the breed to haul heavy loads across Alaska’s Norton Sound region. Known as the “Freight Train of the North,” Malamutes were indispensable partners for survival, assisting in hunting seals and polar bears, transporting goods, and providing warmth in tribal shelters. Frequently mistaken for Siberian Huskies, Malamutes are larger and more robust, designed for strength and endurance rather than speed. Their history as working dogs has shaped their physical abilities and behavioral traits, making them both highly capable and demanding companions. Breed-Specific Traits and Temperament Understanding the Malamute’s unique personality is essential for potential owners. They are highly intelligent but strong-willed and independent, combining loyalty, affection, and playfulness with a persistent “puppy-like charm” into adulthood. Their pack-oriented heritage means they require a confident, consistent leader to prevent dominance issues. Key behavioral traits: Vocalizations: Rather than typical barking, Malamutes are vocal and expressive, often howling, making “woo-woo” sounds, or “singing.” Exercise Needs: Extremely active, requiring a minimum of two hours of vigorous daily exercise; without adequate stimulation, they may become destructive or overly vocal. Prey Drive: High prey drive requires caution around smaller animals and can contribute to same-sex aggression. Grooming: Their thick double coat protects them in freezing climates but leads to heavy seasonal shedding, requiring daily brushing to maintain coat health. Health Needs and Veterinary Considerations Expert veterinary care is critical, as Malamutes are predisposed to several hereditary health conditions, many of which are autosomal recessive. Responsible breeding and early detection are key to maintaining a healthy population. Common health concerns include: Hip Dysplasia: Malformation of the hip joint that can lead to arthritis and reduced mobility; x-ray screening is essential for breeding dogs. Alaskan Malamute Polyneuropathy (AMPN): A neuromuscular genetic disorder causing weakness, muscle wasting, and a characteristic bunny-hopping gait; DNA testing identifies carriers and affected individuals. Day Blindness (Cone Degeneration): Sensitivity to bright light, causing difficulty seeing during the day while retaining night vision. Hypothyroidism: An underactive thyroid that can affect weight, skin, and energy levels. Gastric Dilation and Volvulus (GDV/Bloat): A life-threatening twisting of the stomach, most common in deep-chested breeds, requiring immediate veterinary attention. To reduce these risks, the Alaskan Malamute Club of America mandates testing for hip dysplasia, polyneuropathy, and ocular phenotypes in breeding dogs. Owners are advised to maintain a balanced, protein-rich diet while monitoring weight, as their thick coat can easily conceal obesity. Early socialization and consistent, reward-based training provide the foundation for a healthy, well-adjusted companion. 2. History and Origins The Alaskan Malamute is an ancient Arctic breed originating in Alaska’s Norton Sound region, where it was developed by the Mahlemut Inupiaq people. These dogs were indispensable partners for human survival, assisting in hunting polar bears and seals and providing warmth in tribal shelters during freezing nights. Bred to pull heavy sleds over vast, frozen landscapes, the Malamute earned the nickname “Freight Train of the North” for its exceptional strength and ability to haul freight over long distances. The breed’s reputation for resilience grew during the 1896 Gold Rush, and Malamutes later participated in notable historical missions, including Admiral Byrd’s Antarctic expeditions and World War II search and rescue operations. Their physical and behavioral traits, honed over centuries, allowed them to thrive in extreme Arctic conditions. The American Kennel Club (AKC) officially recognized the Alaskan Malamute in 1935, formalizing the preservation of the breed’s pure bloodlines and distinctive characteristics. While the sources do not explicitly mention the United Kennel Club (UKC), references frequently highlight the role of the Kennel Club (UK) and the importance of using Assured Breeders to maintain breed standards and promote health. To endure harsh Arctic climates, Malamutes evolved several adaptive traits: Insulating Double Coat: A dense, woolly undercoat paired with a coarse, water-repellent outer layer protects against freezing temperatures. Immense Strength: Unlike Siberian Huskies, which were bred for speed, Malamutes prioritize power and substantial bone, enabling them to pull loads multiple times their own body weight. Specialized Features: Erect ears enhance alertness, and the well-furred plumed tail, carried over the back, provides both a majestic appearance and protection from the elements. These adaptations, combined with their strong pack instincts and endurance, establish the Malamute as one of the most capable and iconic Arctic working breeds. 3. Physical Characteristics Size and Sexual Dimorphism Alaskan Malamutes are large, powerful dogs, with a standard height of 23 to 25 inches at the shoulder and a typical weight range of 75 to 85 pounds. The breed exhibits clear sexual dimorphism, with males generally larger and heavier than females. Adult males may reach 25 to 28 inches in height and weigh up to 85 pounds, while females typically measure 23 to 25 inches and weigh between 65 and 75 pounds. Some Malamutes from working lines can surpass these dimensions, reaching weights of up to 100 pounds, emphasizing the breed’s capacity for heavy-duty work. Coat Types and Seasonal Shedding The Alaskan Malamute is equipped with a specialized thick double coat adapted for survival in Arctic climates. This coat consists of: A soft, dense, woolly undercoat that provides insulation. A straight, harsh, water-repellent outer coat that stands off from the body and protects against moisture and wind. Due to this dense coat, Malamutes are heavy shedders year-round. They also experience pronounced seasonal shedding twice annually—spring and autumn—commonly referred to as “blowing” the undercoat. During these periods, daily or even twice-daily brushing is necessary to manage loose fur and prevent matting. Recognizable Markings and Differences from Huskies Distinctive physical features set Malamutes apart from other sled dogs: Tail: A well-furred, plumed tail carried over the back, both functional for warmth and aesthetically striking. Head and Ears: Erect, triangular ears, a broad head, and almond-shaped eyes contribute to an alert and expressive appearance. Coat Colors and Markings: Coat colors include gray, black, sable, and red, always

Predicting Outcomes in Hyperthyroid Cats Treated with Radioiodine

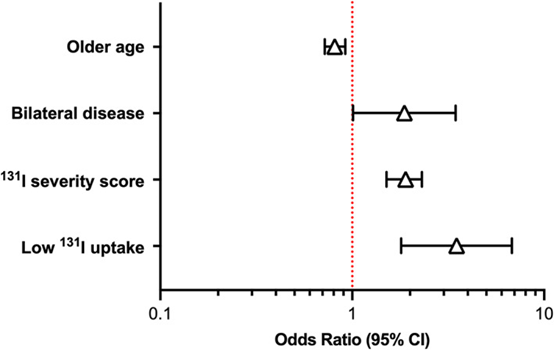

Source: J Vet Intern Med. 2022 Jan-Feb; 36(1): 49–58. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16319. Hyperthyroidism is a common disease in cats, and mostly afflicts cats middle-aged and older. It is caused by the overproduction of thyroid hormone by the thyroid glands. Radioiodine (131 I) is the treatment of choice to restore euthyroidism with a single dose of radiation without producing hypothyroidism for cats receiving the treatment. However, 30% to 50% of 131I‐treated cats develop iatrogenic hypothyroidism after treatment. Besides, 5% to 10% of hyperthyroid cats fail 131I treatment and remain persistently hyperthyroid. To identify pretreatment factors that may help predict persistent hyperthyroidism and iatrogenic hypothyroidism after treatment of cats using a novel 131I dosing algorithm. Peterson, ME and Rishniw, M conducted a study involving one thousand and four hundred hyperthyroid cats treated with 131I. Cats underwent an evaluation that included a complete physical examination, routine laboratory testing (CBC, serum biochemical profile, complete urinalysis), determination of serum thyroid hormone concentrations (total thyroxine [T4], triiodothyronine [T3], and thyroid‐stimulating hormone [TSH]), and qualitative and quantitative thyroid scintigraphy. Pretreatment predictors (clinical, laboratory, scintigraphic, 131I dose, 131I uptake measurements) of treatment failure or iatrogenic hypothyroidism were identified by multivariable logistic regression analysis. In conclusion, Age, sex, serum TSH concentration, bilateral and homogeneous 99mTc‐pertechnetate uptake on scintigraphy, severity score, and percent 131I uptake are all factors that might help predict outcome of 131I treatment in hyperthyroid cats. For detail information please check the original paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8783366/

Breed Related Diseases: Pug

Originating from China, the Pugs were valued by emperors and used to live in luxurious accommodations. In various eras and places, the Pugs were called in different names: Lo-sze (China), Mopsi (Finland), Doguillo (Spain); to name a few. Coming from the Latin word “pugnus,” meaning “fist”, it has been suggested due to the resemblance of the dog’s face to a clenched fist. Pugs are usually at 14 to 18 pounds, both male and female, in weight, and generally at 10 to 14 inches tall at the shoulder. They are square and cobby, with short legs and long body, compactness of form, well- knit proportions, and hardness of developed muscle. They are desirable with large, massive, and round heads. The dark, large, bold, and prominent eyes are globular in shape and shows solicitous expression. The pugs have large and deep wrinkles, with short, blunt, square muzzle. The coat of a pug is fine, smooth, soft, short and glossy, with colors fawn or black. Being bred for centuries, they are lovable dogs. Hunting, guarding, or retrieving are not what they do best, instead, as companions- craving affection and happier when spending time with family. They are known for being an even-tempered breed, with exhibiting stability, playfulness, great charm, dignity, and an outgoing, loving disposition. The pugs usually goes along well with other dogs, cats, and children. Although they are not designed to be jogging companions or beach bunnies, their relatively large size (for a toy breed) and easy-going temperament makes them a perfect on- the- go family companion. Generally, the pugs are healthy, but all dogs have the potential to develop genetic health problems; and it’s important to be aware of the following diseases. Cheyletiella Dermatitis (Walking Dandruff): A skin condition that is caused by a small mite. This may be contagious to other household pets. It is characterized by heavy dandruff, especially down the middle of the back, and needs the veterinarian’s check- up. Pug Dog Encephalitis: This is a unique fatal inflammatory brain disease to Pugs. Due to unknown causes of the disease, there is no known treatment, and diagnosis is only conducted by testing the brain tissue of the dog after it dies. Usually affecting younger dogs, it causes them seizure, blindness, then fall into a coma and die in a few days or weeks. Epilepsy: The Pugs are prone to idiopathic epilepsy: and with seizures for no known reason. Taking the Pug to the vet determines what treatment is appropriate. Nerve Degeneration: Older Pugs that drag their rear, stagger, have trouble jumping up or down, or become incontinent may be suffering from nerve degeneration. The condition usually advances slowly- and the cause is also unknown. Corneal Ulcers: Due to the large and prominent eyes of the Pug’s eyes, these are prone to injuries or development of ulcers on the cornea (the clear part of the eye). If your Pug squints or the eyes look red and tear excessively, contact your vet immediately. Corneal ulcers usually respond well to medication, but if left untreated, can cause blindness or even rupture the eye. Dry Eye: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and pigmentary keratitis are two conditions seen in Pugs. They can occur at the same time, or individually. Dry eye is caused by insufficient tears to stay moist. Your vet can perform tests to determine if this is the cause, which can be controlled with medication and special care. Whereas, Pigmentary keratitis causes black spots on the cornea, especially in the corner near the nose. The pigment can cause blindness if it covers the eyes. Your vet can prescribe medication that will help keep the eyes moist and dissolve the pigment. Both of these eye conditions require life-long therapy and care. Eye Problems: Pugs are prone to a variety of eye problems, including proptosis (the eyeball is dislodged from the eye socket and the eyelid clamps behind it); distichiasis (an abnormal growth of eyelashes on the margin of the eye, resulting in the eyelashes rubbing against the eye); progressive retinal atrophy (a degenerative disease of the retinal visual cells that leads to blindness); and entropion (the eyelid, usually the lower lid, rolls inward, causing the hair on the lid to rub on the eye and irritate it). Allergies: Some Pugs suffer from a variety of allergies, ranging from contact to food allergies. Demodectic Mange: Also called demodicosis, all dogs carry a little passenger called a demodex mite. The mother dog passes this mite to her pups in their first few days of life. The mite can’t be passed to humans or other dogs; only the mother passes mites to her pups. The dog develops patchy skin, bald spots, and skin infections all over the body. Staph Infection: Staph bacteria is commonly found on skin, but some dogs will develop pimples and infected hair follicles if their immune systems are stressed. The lesions can look like hives where there is hair; on areas without hair, the lesions can look like ringworm. Your vet will provide appropriate treatment. Yeast Infection: This is suspected if your Pug started smelling bad, it feels itchy and has blackened, thickened skin. It commonly affects the armpits, feet, groin, neck, and inside the ears. Your vet can prescribe medications to clear this up. Hemi-vertebrae: Short-nosed breeds, such as Pugs, Bulldogs and French Bulldogs, can have misshaped vertebrae. Others will stagger and display an uncoordinated, weak gait between 4 and 6 months of age, while some dogs get progressively worse and may even become paralyzed. The cause of the condition is unknown. Surgery can help. Hip Dysplasia: Many factors, including genetics, environment and diet, are thought to contribute to this deformity of the hip joint. Affected Pugs are usually able to lead normal, healthy lives with proper veterinary attention. Legg-Perthes Disease: It also involves the hip joint. Affected pugs develop insufficiency of blood supply to the head of the femur (the large rear leg bone), and the head of the femur that connects to the

Individualized I-131 Dosing for Feline Hyperthyroidism Treatment

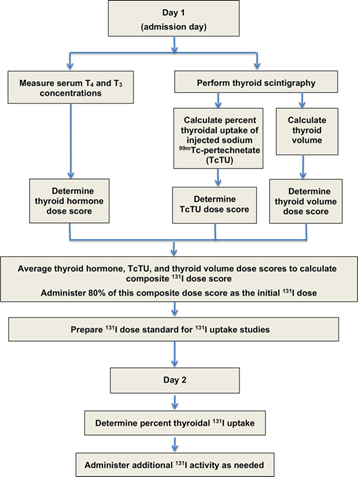

Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Overview of Feline Hyperthyroidism Feline hyperthyroidism is the most common endocrine disorder affecting middle-aged and geriatric cats, driven overwhelmingly by autonomous thyroid adenomas or adenomatous hyperplasia. More than 97 percent of cases result from benign, functional proliferation of thyroid tissue that produces excessive amounts of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) (Peterson, 2013; Broussard et al., 1995). The resulting hypermetabolic state manifests across multiple organ systems. Typical clinical signs include: Progressive weight loss, despite normal or increased appetite Polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria Episodic vomiting or diarrhea A dull or unkempt hair coat Tachycardia and a palpable thyroid nodule in many cases These signs often begin subtly, then intensify as thyroid hormone excess accelerates metabolic turnover and causes secondary strain on cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal systems. 1.2 Limitations of Traditional Radioiodine (I-131) Dosing Radioiodine (I-131) therapy is widely regarded as the treatment of choice for feline hyperthyroidism (Peterson, 2013; Mooney, 2001; Feldman & Nelson, 2015). I-131 concentrates selectively in hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, where emitted beta particles induce cytotoxicity and subsequent glandular fibrosis. Traditional fixed-dose approaches, typically ranging from 3–5 mCi, have historically produced good cure rates Peterson, 2013; Williams et al., 2010; Peterson & Broome, 2015). However, these protocols are increasingly recognized as imprecise, with substantial rates of treatment-related complications: Iatrogenic Hypothyroidism (IH).Fixed-dose regimens often exceed the minimal therapeutic requirement, exposing normal thyroid remnants to unnecessary radiation. Reported IH rates vary widely—from 30 to 80 percent—and represent a major concern in post-treatment management. IH-associated azotemia carries significant prognostic implications. Cats that become hypothyroid and azotemic after treatment have significantly shorter survival times than cats that remain euthyroid or non-azotemic. This underscores the clinical importance of avoiding overtreatment. 1.3 Evidence Supporting Individualized Radioiodine Dosing To mitigate these risks, Peterson and Rishniw (2021) developed a sophisticated, feline-specific dosing algorithm designed to deliver the lowest effective I-131 dose required to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing the likelihood of iatrogenic hypothyroidism and azotemia. Drawing on data from 1,400 hyperthyroid cats, their study established several crucial findings: Median total dose: 1.9 mCi (range 1.0–10.6 mCi)• Considerably lower than historical fixed-dose practices Cure (euthyroid) rate: 74.8 percent, comparable to traditional outcomes Significantly lower complication rates:• 4.1 percent overt hypothyroidism• 17.1 percent subclinical hypothyroidism• Combined rate (~21%) markedly lower than many fixed-dose protocols These outcomes demonstrate that tailored dosing not only achieves therapeutic efficacy but also reduces the risk burden associated with excessive radiation exposure. The Two-Day Algorithmic Protocol The algorithm employs a structured, multiparametric approach based on objective measures of disease severity and biological iodine-handling capacity. Day 1: Initial Composite Dose (80 percent administered) A composite dose score is calculated by integrating three major disease indicators: Serum T4 and T3 concentrations Thyroid tumor volume, measured using thyroid scintigraphy Technetium uptake (TcTU), a marker of functional thyroid activity Only 80 percent of this calculated composite dose is administered initially to avoid overtreatment. Day 2: Uptake-Based Dose Adjustment Approximately 24 hours later, the thyroidal I-131 uptake is measured to determine how effectively the gland concentrates radioiodine. A supplemental dose is then administered as needed. In the study, 1,380 out of 1,400 cats required additional I-131 on Day 2, highlighting the essential role of uptake-based adjustment and the variability in individual glandular kinetics. This two-step method mirrors the logic of precision dosing used in pharmaceutical sciences:deliver enough activity to neutralize the hyperfunctioning tissue, but not so much that normal thyroid function is extinguished or renal sequelae are exacerbated. 2. Radioiodine Pharmacology The therapeutic use of radioiodine (131I) in feline hyperthyroidism rests on a sophisticated interplay between thyroid physiology, nuclear physics, and disciplined radiation-safety practices. The following section synthesizes the core pharmacologic principles, uptake kinetics, veterinary dosimetry, and regulatory safety frameworks that underpin this therapy. 2.1 Mechanism of 131I Radioiodine (131I) exploits the thyroid gland’s unique ability to concentrate iodine for hormone synthesis. Targeting mechanism.The follicular cells of the thyroid actively transport iodine from the bloodstream using the sodium–iodide symporter (NIS). Because the NIS cannot distinguish between stable iodine and 131I, hyperfunctional thyroid tissue accumulates radioiodine to levels that far exceed blood concentrations, often by a factor of 500-fold. In hyperthyroid cats, adenomatous tissue is especially efficient at concentrating 131I. Destructive mechanism.Once incorporated into the gland, 131I decays as a dual-emitter. Its therapeutic activity derives largely from the emission of high-energy beta (β–) particles, which: have a short path length (typically 0.5–2 mm, mean 0.8 mm), generate highly localized cell injury, induce pyknosis, necrosis, and progressive fibrosis over subsequent weeks. This short-range cytotoxicity spares adjacent structures—including the parathyroid glands—substantially reducing the risk of hypoparathyroidism. Selective destruction.In hyperthyroid cats, normal thyroid tissue is usually suppressed by low endogenous TSH levels and therefore takes up minimal 131I. This endogenous suppression optimizes therapeutic selectivity by focusing the radiation burden on the diseased tissue. 2.2 Thyroid Uptake Kinetics Biological and effective half-life.While the physical half-life of ^131I is 8.04 days, the effective half-life in hyperthyroid cats is shorter—approximately 2.3 to 2.54 days—reflecting both physical decay and biological elimination. Renal clearance.Elimination of circulating 131I occurs primarily via renal excretion. Cats with renal disease may retain 131I longer, increasing total radiation burden and necessitating more cautious monitoring. Role of uptake measurement.In individualized radioiodine dosing protocols, 24-hour thyroidal 131I uptake is measured to refine and optimize the total therapeutic dose. This uptake assessment serves as a physiologic indicator of how efficiently the thyroid tissue concentrates radioiodine, allowing clinicians to adjust the administered activity accordingly. Low uptake values signal reduced radioiodine concentration and therefore pose a risk of undertreatment, potentially leading to persistent hyperthyroidism. Conversely, high uptake values increase the likelihood of excessive radiation delivery, elevating the risk of iatrogenic hypothyroidism. As such, measuring thyroidal 131I uptake is pivotal for balancing therapeutic efficacy with preservation of normal endocrine function, and it represents a central component of individualized dosing algorithms. 2.3 Veterinary Dosimetry Considerations Modern veterinary dosimetry emphasizes delivering the lowest effective dose to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing complications such as hypothyroidism and azotemia. The individualized 2-day dosage algorithm used by Peterson and Rishniw (2021)

Lameness, Generalised Myopathy and Myalgia in an Adult Cat with Toxoplasmosis- Abstract Butts DR, Langley-Hobbs SJ.

Source: JFMS Open Rep. 2020 Mar 13;6(1):2055116920909668. doi: 10.1177/2055116920909668. A 2-year-old female neutered domestic shorthair cat presented with an 18-month history of intermittent lameness on all four limbs. The cat was markedly lame on all four limbs. Physical examination detected pain on palpation of the calcaneus bone and Achilles tendon bilaterally, and general resentment to handling. Investigations revealed an elevated creatine kinase, a positive Toxoplasma gondii IgG titre, toxic neutrophilic inflammation within the Achilles tendon bursae, electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies consistent with a diffuse muscular disease, and histopathology of the muscle consistent with a chronic and diffuse myopathy. Arthrocentesis samples and an antinuclear antibodies titre were normal. Prior treatment with meloxicam had been ineffective. A 6-week course of clindamycin was prescribed; an improvement was seen within 3 days and clinical resolution at 3 months. The cat remained clinically normal after 20 months. This report suggests toxoplasmosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in cats with myopathies or lameness in the absence of other causes. Figure 1 Toe-walking on the left forelimb with hunched posture. (b) Weightbearing on the dorsal aspect of the left carpus. (c) Sitting back on the hindlimbs and non-weightbearing on the forelimbs Figure 2 Neutrophil containing a duck egg blue cytoplasmic inclusion (far left) seen on cytology of Achilles tendon bursal fluid (suspected to be a lupus cell or Döhle body)