Oliver Organista, LA

Canine babesiosis is a tick-borne, protozoal, haemoparasitic disease that can cause varying degrees of haemolytic anaemia, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia and fever. It is very endemic to different parts of the world, and presents varying clinical, hematological, and pathological manifestation depending on the species and subspecies involved.1,2 There are two hosts for the transmission of Babesia spp., viz. invertebrate (tick) and vertebrate host. Dogs are one among the many targets of Babesia spp., causing canine babesiosis, and now there are clinical evidences of possible vertical transmission too. Dogs of all ages can be affected with Babesia spp., but young puppies are more commonly affected.

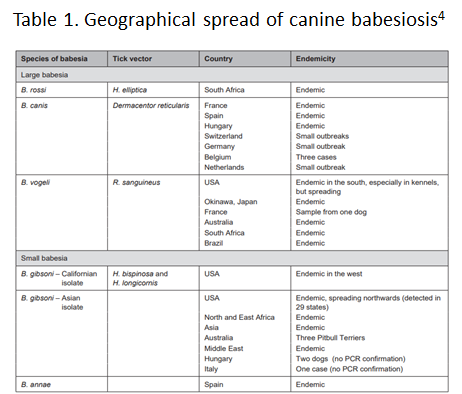

Two Babesia parasites were thought to occur in dogs; the relatively large intra-erythrocytic piroplasm referred to as Babesia canis and a smaller parasite, known predominantly as the cause of canine babesiosis in Asia, Babesia gibsoni. B. canis has been reclassified into three separate species (B. canis, B. rosi, B. vogeli) on the basis of immunity, serological testing, vector specificity and molecular phylogeny

At least 4 genetically and clinically distinct small piroplasms affect dogs which include: Babesia gibsoni–originally described in India nearly a century ago and now occurring sporadically in other parts of the world including the Australia; Babesia conradae, a piroplasm that occasionally infects dogs in California; Theileria annae, a Babesia microti-like parasite that has so far been reported only in northwest Spain, transmitted by Ixodes hexagonus ; and a fourth small piroplasm, B. (=T.) equi has also been reported in dogs in Spain.³

Prevalence of Babesiosis

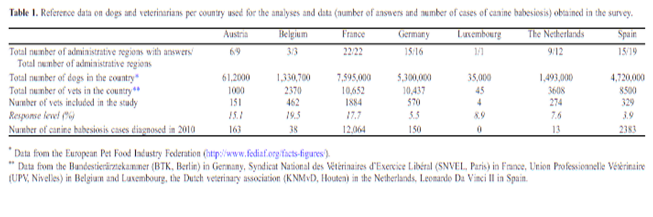

The incidence of canine babesiosis vary considerably from one country to another depending on the distribution of the causative parasite and their specific vectors.

Table below shows the data gathered during the Questionnaire-based survey on the distribution and incidence of canine babesiosis in countries of Western Europe.5

DIAGNOSIS, SYMPTOMS, AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis. In the past, babesiosis was diagnosed by seeing the parasite on a blood smear.

Other diagnostic tests are becoming more readily available, including FA (fluorescent antibody) staining of the organism and ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) tests. A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is also available and is commonly used to diagnose babesiosis. The PCR test has the advantage in that it can detect all four species of Babesia.

Serologic or antibody titer testing in the diagnosis of babesiosis has limitations. A positive test result is dependent on an antibody response by the infected dog, which may take up to ten days to develop. Once a dog has developed antibodies to babesiosis, they may persist for years and this must be considered when performing follow-up tests.6

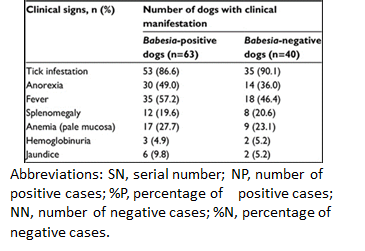

Symptoms. Dogs typically present with the acute, severe form of babesiosis, which is characterized by findings such as abnormally dark urine, fever, weakness, pale mucous membranes, depression, swollen lymph nodes, and an enlarged spleen. Potential complications: Bleeding problems, a severe type of anemia that leads to jaundice, organ damage, death.7

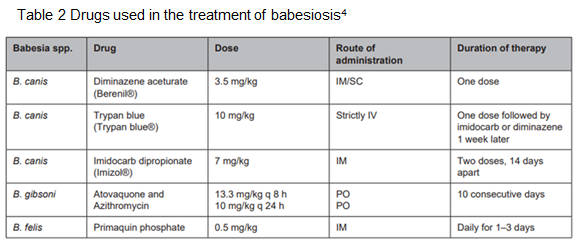

Treatment. The FDA approved treatment for babesiosis is imidocarb diproprionate. A combination therapy of quinine, azithromycin, atovaquone, and/or clindamycin is being researched and may become more common to treat dogs within the US or Canada in the future.

Clindamycin, the treatment of choice for Babesia microti, the main Babesia species that infects humans, can also be used against Babesia in dogs. Clindamycin is a readily available antibiotic and is an excellent starting point for treatment in many dogs. Your veterinarian will discuss any alternative and adjunctive treatments with you.7

TRANSMISSION AND PREVENTION OF BABESIOSIS

How is dog Babesia transmitted?

Transmission. In most cases, Babesia organisms are spread to dogs through the bite of an infected tick but is not likely to be transmitted until a tick is attached for 36 hours.

However, some studies suggest that infected dogs with open mouth sores can pass on the infection to other dogs through a bite, and infected pregnant females can transmit babesiosis to their unborn puppies. It can also be transmitted by the needle passage of infected blood, inadvertently in the case of blood transfusion or deliberately during experimental studies.

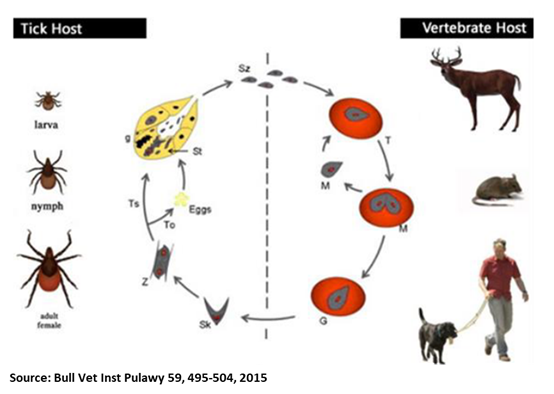

Generic Life Cycle of Babesia spp.10

Generic life cycle of Babesia spp. Sporozoites (Sz) are injected into a vertebrate host blood system, during the blood meal of an infected tick. After invasion, Sz differentiate into trophozoites (T). Trophozoites undergo asexual division into two or four merozoites (M) in the infected red blood cells. Merozoites exit the red blood cells and invade new ones. Some groups of merozoites transform into gamonts or pregamotyces (G). The process of gamogony and sporogony takes place in the tick. Gamonts ingested by a tick feeding on an infected host differentiate in the gut into gametes (called ray bodies or Strahlenkorper – (Sk)) that fuse forming a diploid zygote (Z, gamogony). Via meiosis division, zygotes give rise to motile haploid kinetes. After haploid kinetes multiply by sporogony, they penetrate the tick haemolymph and organs. The final stage of the development occurs in the salivary glands (Sg), where differentiation and multiplication occur. Kinetes transform into sporozoites that infect the vertebrate host after vector development into a subsequent life stage – larvae to nymph, nymph to adult (transstadial transmission, Ts). In large Babesia spp. kinetes also invade the tick ovaries and eggs, and infective sporozoites are formed in the salivary glands of the next generation larvae. This process is called transovarial transmission (To). Adopted and reproducted from Schnittger et al. 9

How ticks spread disease11

Ticks transmit pathogens that cause disease through the process of feeding.

- Depending on the tick species and its stage of life, preparing to feed can take from 10 minutes to 2 hours. When the tick finds a feeding spot, it grasps the skin and cuts into the surface.

- The tick then inserts its feeding tube. Many species also secrete a cement-like substance that keeps them firmly attached during the meal. The feeding tube can have barbs which help keep the tick in place.

- Ticks also can secrete small amounts of saliva with anesthetic properties so that the animal or person can’t feel that the tick has attached itself. If the tick is in a sheltered spot, it can go unnoticed.

- A tick will suck the blood slowly for several days. If the host animal has a bloodborne infection, the tick will ingest the pathogens with the blood.

- Small amounts of saliva from the tick may also enter the skin of the host animal during the feeding process. If the tick contains a pathogen, the organism may be transmitted to the host animal in this way.

- After feeding, most ticks will drop off and prepare for the next life stage. At its next feeding, it can then transmit an acquired disease to the new host.

How can I prevent my dog from getting Babesiosis?12

Prevention. Preventing the disease is key, as treatment can be expensive. It takes at least 48 hours for Babesia to be transmitted. To help prevent Babesiosis, ensure your dog is on tick prevention medication year-round – this can be an effective way to prevent a host of tick-borne diseases.

Check your dog daily for ticks, and correctly remove any parasites you discover – once the tick starts to feed on your pet,

Bibliography

- Di Cicco MF, Birkenheuer AJ. Canine babesiosis. Infectious disease/parasitology. Consultants on Call/NAVC Clinician’s Brief; 2012.

- Lobetti R. Hematological changes associated with tick-borne diseases (infectious/parasitic diseases). In: World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings. October 6–9, 2004, for 29th WSAVA Congress Proceedings.

- Peter J. Irwin Blood, Bull Terriers and Babesiosis: a Review of Canine Babesiosis. World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2007

- Johan P Schoeman) titel: Canine Babesiosis pg. 60

- Lénaïg Halos, Isabelle Lebert, David Abrialal Questionnaire-based survey on the distribution and incidence of canine babesiosis in countries of Western Europe. Parasite. 2014. 21:13

- https://www.wellnessvet.com.hk/dogs-disease-tick-fever-babesia-canis-vs-babesia-gibsoni/

- Ryan Llera and Ernest Ward. “Babesiosis in Dogs” (https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/babesiosis-in-dogs)

- Adebayo O, Ajadi R, Omobowale T, Omotainse S, Dipeolu M, Nottidge H, Otesile E, “Reliability of clinical monitoring for the diagnosis of babesiosis in dogs in Nigeria”, Dovepress (https://www.dovepress.com)

- Schnittger , Rodriguez A.E., Florin-Christensen M., Morrison D.A.: Babesia: a world emerging. Infect Genet Evol 2012, 12, 1788–1809

- Krzysztof Kostro, Krzysztof Stojecki, Maciej Grzybek, Krzysztof Tomczuk, “Characteristics, immunological events, and diagnostics of Babesia spp. infection, with emphasis on Babesia canis, Bull Vet Inst Pulawy 59, 495-504, 2015

- How ticks spread disease, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html)

- “Babesiosis in Dogs: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment”, Western Carolina Regional Animal Hospital & Veterinary Emergency Hospital (https://www.wcrah.com)