Bartonella henselae: An Infectious Pathogen among Cats

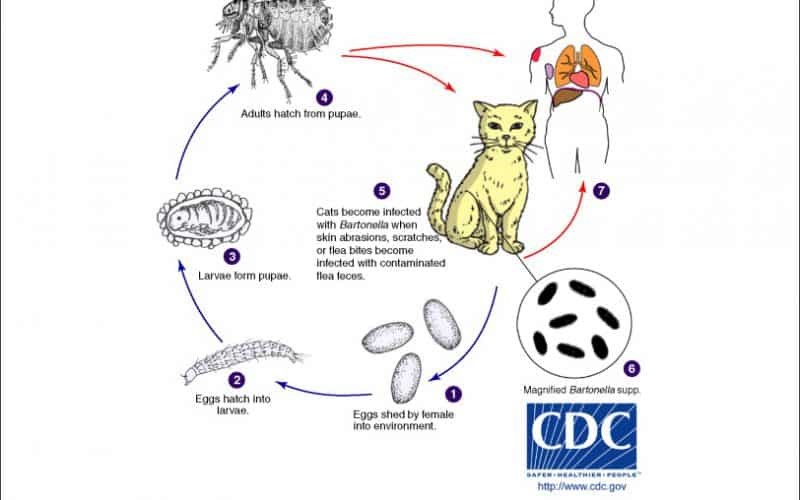

Table of Contents Maigan Espinili Maruquin 1. Introduction Overview of Bartonella henselae as a Significant Feline and Zoonotic Pathogen Bartonella henselae is a small, fastidious, Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium with a global distribution. It exhibits a marked tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes, enabling the establishment of chronic, relapsing bacteremia that may persist for months or even years in infected hosts. Domestic cats are the primary mammalian reservoir and represent the principal source of zoonotic transmission to humans. Kittens and feral cats typically harbor higher bacterial loads, although subclinical infection is widespread across the global feline population. Reported bacteremia prevalence in apparently healthy cats ranges from 8% to 56%, depending on geographic region and flea exposure. The primary competent vector for B. henselae is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), within which the organism replicates in the flea gut and is excreted in flea feces (commonly referred to as flea dirt). These contaminated feces can remain infectious in the environment for at least nine days, facilitating indirect transmission. Importance in Companion Animal Medicine and Public Health From a companion animal medicine perspective, B. henselae is clinically significant because most infected cats function as asymptomatic carriers, silently sustaining zoonotic risk. Nevertheless, increasing evidence links B. henselae infection to sporadic but severe feline disease manifestations, including endocarditis, myocarditis, and ocular inflammatory conditions such as uveitis. In dogs, which are considered accidental hosts, bartonellosis is often more pathogenic and has been strongly associated with culture-negative endocarditis and granulomatous inflammatory disease. In public health, B. henselae is best known as the primary etiological agent of Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) in humans. Transmission most commonly occurs when cat claws or oral cavities become contaminated with infected flea feces, which are then inoculated into human skin through a scratch or bite. Immunocompetent individuals typically develop a self-limiting illness characterized by regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and a papule at the site of inoculation. Immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients, are at risk for severe and potentially fatal complications, such as bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis, encephalitis, and endocarditis, reflecting the organism’s vasoproliferative potential. Scope of the Review and Relevance to Clinical Practice A clear understanding of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and persistence mechanisms of B. henselae is essential for effective clinical management and disease prevention. Diagnosis remains particularly challenging, as the organism is highly fastidious and slow-growing, frequently resulting in false-negative blood culture findings and so-called “culture-negative” infections. Although molecular assays such as PCR and serological testing are widely employed, interpretation is complicated by intermittent bacteremia and the high background seroprevalence among healthy cats. In clinical practice, adoption of a One Health framework is critical. Veterinarians play a central role in mitigating zoonotic risk through owner education, emphasizing strict, year-round flea control, appropriate hygiene, and cautious interaction with cats, especially in households containing immunocompromised individuals. Management is further complicated by the absence of a standardized antimicrobial protocol capable of reliably achieving complete bacteriological clearance in feline hosts. To conceptualize its biological behavior, B. henselae may be likened to a “stealthy hitchhiker.” By residing within erythrocytes and vascular endothelium, the organism evades immune surveillance, periodically re-emerging only to secure transmission via a passing flea. 2. Characteristics and Epidemiology 2.1 Taxonomy and Microbiological Characteristics The genus Bartonella comprises small, thin, fastidious, and pleomorphic Gram-negative bacilli. These organisms are facultative intracellular pathogens with a highly specialized biological niche characterized by a pronounced tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes (red blood cells). Following host entry, Bartonella spp. proliferate within membrane-bound vacuoles, often referred to as invasomes, inside vascular endothelial cells. Periodic release into the bloodstream allows subsequent invasion of erythrocytes, within which the bacteria may persist until cellular senescence or destruction occurs (Cunningham and Koehler 2000; LeBoit 1997). Transmission is predominantly arthropod-borne, involving vectors such as fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), ticks, lice, and sand flies. Although Bartonella species have been isolated from a wide range of mammalian hosts, including rodents, rabbits, canids, and ruminants, domestic and feral cats represent the principal mammalian reservoir for the most epidemiologically and clinically significant zoonotic species, particularly B. henselae (Chomel et al., 1996; Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Guptill, 2012). 2.2 Global Distribution and Seroprevalence Bartonella species exhibit a global distribution, although prevalence varies markedly according to environmental and ecological conditions. In European feline populations, reported antibody prevalence ranges from 8% to 53% (Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Zangwill, 2013), while global serological evidence of exposure in cats spans approximately 5% to 80% (Guptill, 2012). The epidemiology of Bartonella infection is strongly influenced by geography, climate, and flea density. The highest prevalence rates are consistently observed in warm, humid temperate and tropical regions, where environmental conditions favor the survival and propagation of C. felis. In contrast, in colder climates, such as Norway, Bartonella infection in cats is reported to be rare or virtually absent, reflecting the limited persistence of flea vectors under such conditions. 2.3 Species Diversity and Genotypes Although 22 to 38 Bartonella species have been described to date, Bartonella henselae remains the most frequently detected species in both domestic cats and humans. Feline populations may also harbor Bartonella clarridgeiae, identified in approximately 10% of infected cats, while B. koehlerae is detected far less commonly (Guptill, 2012). Considerable regional variation exists among B. henselae genotypes, which are broadly classified into Houston-1 (Type I) and Marseille (Type II) strains. Type II (Marseille) predominates among feline populations in the western United States, western continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Type I (Houston-1) is the dominant genotype in Asia, including Japan and the Philippines, and is most frequently isolated from human clinical cases worldwide, even in regions where Type II strains are more prevalent among cats. Beyond domestic cats, Bartonella infections have been documented in non-domestic felids, including African lions, cheetahs, and various neotropical wild cat species, underscoring the broad ecological adaptability of the genus (Guptill, 2012). To conceptualize its ecological behavior, Bartonella may be viewed as a “weather-dependent squatter.” It establishes itself most successfully in warm, densely populated environments rich in flea vectors,

Feline Pancreatic Lipase (fPL)

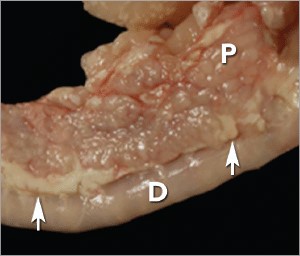

Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Pancreatitis appears to be a common disease in cats,1 yet it remains frustratingly difficult to establish a clinical diagnosis with certainty. Clinicians must rely on a combination of compatible clinical findings, serum feline pancreatic lipase (fPL) measurement, and ultrasonographic changes in the pancreas to make an antemortem diagnosis, yet each of these 3 components has limitations. Acute Versus Chronic Pancreatitis Acute pancreatitis is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation, with variable amounts of pancreatic acinar cell and peripancreatic fat necrosis (Figure 1).1 Evidence is mounting that chronic pancreatitis is more common than the acute form, but sonographic and other clinical findings overlap considerably between the 2 forms of disease.1-3 Diagnostic Challenges Use of histopathology as the gold standard for diagnosis has recently been questioned because of the potential for histologic ambiguity.3,4 A seminal paper exploring the prevalence and distribution of feline pancreatic pathologic abnormalities reported that 45% of cats that were apparently healthy at time of death had histologic evidence of pancreatitis.1 The 41 cats in this group included cats with no history of disease that died of trauma, and cats from clinical studies that did not undergo any treatment (control animals). Conversely, multifocal distribution of inflammatory lesions was common in this study, raising the concern that lesions could be missed on biopsy or even necropsy. Prevalence Such considerations help explain the wide range in the reported prevalence of feline pancreatitis, from 0.6% to 67%.3 The prevalence of clinically relevant pancreatitis undoubtedly lies somewhere in between, with acute and chronic pancreatitis suggested to represent opposite points on a disease continuum.2 FIGURE 1. Duodenum (D) and duodenal limb of the pancreas (P) in a cat with acute pancreatitis and necrosis; well-demarcated areas of necrosis are present at the periphery of the pancreas in the peripancreatic adipose tissue(arrows). Courtesy Dr. Arno Wuenschmann, Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory Risk factors No age, sex, or breed predisposition has been recognized in cats with acute pancreatitis, and no relationship has been established with body condition score.3-5 Cats over a wide age range, from kittens to geriatric cats, are affected; cats older than 7 years predominate. In most cases, an underlying cause or instigating event cannot be determined, leading to classification as idiopathic.3 Abdominal trauma, sometimes from high-rise syndrome, is an uncommon cause that is readily identified from the history.6 The pancreas is sensitive to hypotension and ischemia; every effort must be taken to avoid hypotensive episodes under anesthesia. Comorbidities In cats with acute pancreatitis, the frequency of concurrent diseases is as high as 83% (Table 1).2 Pancreatitis complicates the management of some diabetic cats and may induce, for example, diabetic ketoacidosis.7 Anorexia attributable to pancreatitis can be the precipitating cause of hepatic lipidosis.8 The role of intercurrent inflammation in the biliary tract or intestine (also called triaditis) in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis is still uncertain. Roles of Bacteria In one study, culture-independent methods to identify bacteria in sections of the pancreas from cats with pancreatitis detected bacteria in 35% of cases.9 This report renewed speculation about the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis, and the potential role that the common insertion of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct into the duodenal papilla may play in facilitating reflux of enteric bacteria into the “common channel” in cats. Awareness of triaditis may affect the diagnostic evaluation of individual patients. Table 1. Clinical Data from 95 Cats with Acute Pancreatitis (1976—1998; 59% Mortality Rate) & 89 Cats Diagnosed with Acute Pancreatitis (2004—2011; 16% Mortality Rate) PARAMETER HISTORICAL DATA* CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† SURVIVING CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† Number of Cats 95 89 75 ALP elevation 50% 23% 18% ALT elevation 68% 41% 36% Apparent abdominal pain 25% 30% 32% Cholangitis NA 12% 11% Concurrent disease diagnosed NA 69% 68% Dehydration 92% 37% 42% Diabetic ketoacidosis NA 8% 5% Diabetes mellitus NA 11% 12% Fever 7%‡ 26% 11% GGT elevation NA 21% 18% Hepatic lipidosis NA 20% 19% Hyperbilirubinemia 64% 45% 53% Icterus 64% 6% 6% Vomiting 35%—52% 35% 36% ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; GGT = gamma glutamyl transferase; NA = not available * Summarized from 4 published case series; a total of 56 cats had acute pancreatitis diagnosed at necropsy and 3 by pancreatic biopsy5,8,10,11 † Data obtained from reference12 ‡ 68% of cats were hypothermic DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION Many cats with pancreatitis have vague, nonspecific clinical signs, which make diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical signs related to common comorbidities, such as anorexia, lethargy, and vomiting, may overlap with, or initially mask, the signs associated with pancreatic disease. Early publications on the clinical characteristics of acute pancreatitis required necropsy as an inclusion criterion, presumably skewing the spectrum of severity of the reported cases.5,8,10,11 Cats with chronic pancreatitis were excluded from these reports. Clinical Findings Table 1 lists common clinical findings in cats from necropsy-based reports and a recent series of 89 cats with acute pancreatitis studied by the authors.12 Note the lower prevalence of most clinical findings in the cats diagnosed clinically rather than from necropsy records. In our evaluation of affected cats, 17% exhibited no signs aside from lethargy and 62% were anorexic. Vomiting occurs inconsistently (35%—52% of cats). Abdominal pain is detected in a minority of cases even when the index of suspicion of pancreatitis is high. About ¼ of cats with pancreatitis have a palpable abdominal mass that may be misdiagnosed as a lesion of another intra-abdominal structure. Laboratory Analyses Hematologic abnormalities in cats with acute pancreatitis are nonspecific; findings may include nonregenerative anemia, hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, or leukopenia. Serum biochemical profile results vary (Table 1). In our acute pancreatitis case series, 33% of cats had no abnormalities in their chemistry results at presentation.12 Serum cholesterol concentrations may be high in up to 72% of cases. Some cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with severe clinical syndromes, such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure, that influence some serum parameters, such as albumin, liver enzymes, and coagulation tests. Plasma ionized calcium concentration may be low, and has

Concurrent with T-zone lymphoma and high-grade gastrointestinal cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma in a dog

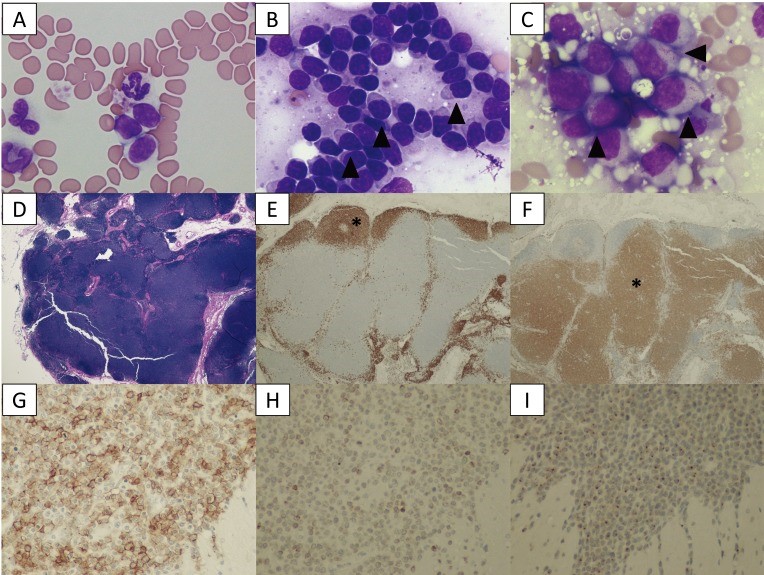

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5402196/ A 9-year-old, spayed female Golden Retriever dog showed lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy, secondary to suspected chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Small-to-intermediate lymphocytes were observed from the cytological examination of the right popliteal lymph node via a fine-needle aspirate. The dog was suspected to have a low-grade lymphoma based on the finding of cytology. Also, ultrasonography reveled thickened lesions in the stomach and small intestine. Histopathology of the popliteal lymph node and small intestine revealed a simultaneous presence of T-zone lymphoma (TZL) and high-grade gastrointestinal (GI) cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements assay suggested that both lymphomas, though both originated in the T-cells, derived from different genes. The dog died 15 days after diagnosis, despite chemotherapy. Fig. 1. A–C: Cytological images on day 1. (A) Peripheral blood smear. Increased numbers of small lymphocytes. (B) Cytology of the popliteal lymph node biopsy. Most lymphocytes are small-to-intermediate, mature lymphocytes. Some lymphocytes show a “hand mirror” type of cytoplasmic extension (arrowhead) (Wright-Giemsa stain, × 400). (C) Slide preparation of tissue from the small intestine. The lymphocytes are intermediate-to-large, immature cells, and some display azurophilic granules in the cytoplasm (LGLs, arrowhead). D–F: Histological images of popliteal lymph node tissue. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. (E) The lymphocytes with fading follicular structures are CD20 positive (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD20, a hematoxylin counterstain. (F) The nodal capsule (CD3 positive) is thinned without the involvement of the perinodal tissue (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD3, hematoxylin counterstain. G–I: Histological images of the intestinal tissue. All lymphocytes are positive for CD20 (G), CD3 (H) and granzyme B (I). Fig. 2. (A) Transverse ultrasound image on day 1 showing a thickened intestinal wall (approximately 9.0 mm, arrowhead). (B) Post-contrast transverse CT image on day 2 also showing a thickened intestinal wall (arrowheads). The intrathoracic and abdominal lymph nodes are enlarged. Fig. 3. PARR analysis. (A) The peripheral blood sample shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. (B) The intestinal tissue sample also shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. The two tumors demonstrate clonal expansions from different primers.

Breed-related disease: Thai Cat

The Thai Cat is an old, but recently recognized breed that is related to the Siamese cat originated in Thailand, where it is actually referred to as the Wichien-Maat, which translates to “moon diamond.” This breed is also commonly referred to as the Traditional, or Old-Style, Siamese. In the 1800s, the first Wichien-Maat cats arrived in Great Britain as a gift to the royal family, where they soon become very popular. The Western breeders renamed the breed to Siamese and started to improve its looks with selective breeding. Thus emerged a cat with finely boned slimmer body, longer head, and more intense sapphire blue eyes. Eventually, the new-styled Siamese was the center of attention and many breeders preferred the new look over the original one. Luckily in the 1950s, some breeders enjoyed the original appearance of these cats and started to breed them to get the original qualities back into the breed. At this point, the two breeds started to diverge. And in 1990, the Thai name was given to cats that had the classic look of Traditional Siamese cats. Finally, in 2009, TICA gave the Thai an Advanced New Breed status. The Thai cat is a shorthaired cat breed that has a flat, short coat that is soft. Their bodies feature medium-sized bones in the legs, head, and tail. And they have a wedge-shaped muzzle, ears that are broad at the base, and a long, flat forehead that distinguishes it from other pointed breeds. These cats also have striking blue eyes that complement their pointed coat beautifully. The Thai is an attention-seeking and demanding breed that craves human companionship. These cats form deep bonds with their owners and will follow them around the house, this breed doesn’t understand the concept of privacy, and the Thai will shadow your every move . While being the center of your cat’s universe has its perks, this amount of devotion can sometimes be too much! Health and Potential Health Problems The Thai is generally a healthy breed that can live very long. Although they aren’t prone to an array of genetic health problems like some other cat breeds, certain issues have been observed in these cats. This doesn’t mean that your cat is going to be affected. However, it is better to learn about any potential problems before bringing a new cat home. Crossed eyes : This condition occurs when small muscles in the eye are stretched out and don’t allow normal movements of the eye. A cat can be born with this condition or develop it later in life. Cats that are born with it don’t experience any problems and have normal lives. However, if the condition appears later in life it is usually because of an underlying issue. Symptoms include uncoordinated eye movement, lack of movement in one eye, seizures, and lethargy. Treatment varies depending on the underlying issue and can include antibiotics or surgery. Kinked Tail : This condition is caused by a recessive gene and it is sometimes seen in Thai Cats. This means that even though both parents have normal tails a kitten can be born with a curled or kinked tail. This condition doesn’t affect the health of a cat. However, affected cats are disqualified from show rings. Gangliosidosis : It’s an inherited disease that causes a cat to lack an enzyme that is required to metabolize certain lipids., excess fats accumulate within the cells disrupting their normal function. Symptoms include in-coordinate walk, enlarged liver, tremors, and visual impairment They are usually observed in kittens between 1 to 5 months of age. Unfortunately, there is no cure for this disease and the affected kittens die when they are 8 months old. However, DNA testing is available and is used to improve breeding programs. Sources: https://www.petguide.com/breeds/cat/thai-cat/ https://thedutifulcat.com/thai-cat/ Photo credit: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Thai_cat

Breed-related disease: Newfoundland

The Newfoundland is a large working dog. They can be either black, brown, grey, or white-and-black. However, in the Dominion of Newfoundland, before it became part of the confederation of Canada, only black and Landseer colored dogs were considered to be proper members of the breed. They were originally bred and used as working dogs for fishermen in Newfoundland. Because of its heavy coat, the Newfie does not fare well in hot weather. It should be kept outdoors only in cold or temperate weather , and in summer, the coat may be trimmed for neatness and comfort, and brushed daily to manage excess shedding and prevent the coat from matting. The dog is at its best when it can move freely between the yard and the house, but still needs plenty of space indoors to stretch properly. Daily exercise is essential, as is typical with all work dogs. Newfoundland is known for his intelligence, loyalty, and sweetness. Even though he is a terrific guard dog, his gentle and docile disposition makes him an excellent choice for as a family dog. He thinks he’s a lap dog, and loves to lean on people and sit on their feet. The Newfie is a natural lifesaver and can be a good assistant for parents who have a swimming pool or enjoy taking the kids to the lake or ocean, although he should never be solely responsible for their safety. Let it be said that the Newfie isn’t perfect, his heroic nature notwithstanding. Any dog, no matter how nice, can develop obnoxious levels of barking, digging, counter-surfing and other undesirable behaviors if he is bored, untrained or unsupervised. And any dog can be a trial to live with during adolescence. In the case of the Newfie, the “teen” years can start at six months and continue until the dog is about two years old. We know you care for your pet that’s why gather some of the various health problems that are common in the breed. Subaortic Stenosis (SAS) This is an inherited disease in Newfoundland’s, although the mode of inheritance appears complicated and is not yet completely understood. A ring of tissue forms below the aortic valve in the heart, restricting the blood flow and increasing the pressure within the heart. The heart tissue overgrows in response to the increased pressure, outgrowing its own blood supply and causing scar tissue to develop that interferes with the electrical impulses in the heart. Puppies can develop a murmur throughout their first year of life, but usually those with significant disease develop murmurs within the first 9 weeks of life. Occasionally, a puppy will have no murmur at a young age, but when checked again at one year, will have developed the disease. Pulmonic Stenosis (PS) In this disease a ring of tissue forms below the pulmonic valve in the heart. It causes murmurs and may affect the dog’s health and life span, depending on the severity and if it appears in conjunction with other defects. Allergies Newfoundland, as well as most other breeds of dogs may allergies to food, fleas, pollen or other environmental allergens. Typically allergies cause skin problems, recurring ear infections or digestive problems. Medications, proper parasite control, and sometimes diet changes can effectively manage many allergies. Panosteitis (Pano) This is a painful inflammatory bone disease of young, rapidly growing dogs. Pano causes lameness in the affected limb and the lameness may “rotate” among all four legs. It is usually a self-limiting condition that most dogs outgrow. The dog may require some limitation of activity, ie no free play, and anti-inflammatory medication if the pup is very painful. Pano commonly occurs between 6 months and 18 months, but is known to occur in older dogs, and tends to run in families. Source: http://www.newfhealthandrescue.org/health.html http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/newfoundland#health Photo credit: https://www.freepik.com/premium-photo/purebred-newfoundland-dog_5575063.htm

Oriental Shorthair White Paper: Breed Characteristics, Health Risks and Care Guidelines

1. Introduction Brief History and Origin of Oriental Shorthairs The Oriental Shorthair is a feline breed classified as a Siamese hybrid, forming part of the larger Oriental Breed Group, which includes the Siamese and Balinese. It is considered a man-made breed, intentionally developed in post–World War II England during the 1950s, when breeders sought to rebuild Siamese lineage programs. To achieve greater phenotypic diversity, the Siamese was crossed with breeds such as the Russian Blue, British Shorthair, Abyssinian, and domestic shorthairs. These early outcrosses produced non-pointed kittens that were subsequently bred back to Siamese lines. The objective was clear, to create a cat identical to the Siamese in type and temperament, but available in a wider range of colors and patterns. While initial color variants were treated as separate breeds, the expanding number of phenotypes prompted consolidation. All non-pointed Siamese-type cats were eventually grouped under one breed name, the Oriental Shorthair. The breed entered the United States during the 1970s and rapidly gained recognition. Popularity, Temperament, and Suitability as Companion Animals The Oriental Shorthair remains popular due to its elegant lines, remarkable behavioral traits, and its extraordinary spectrum of colors, which has earned it the informal name “the rainbow cat.” More than 280 to nearly 300 color and pattern combinations have been documented, with common variations including ebony, white, chestnut, and blue. Its defining traits include: Social and Affectionate: Orientals form intense bonds with their caregivers. They thrive on interaction and are known to experience withdrawal or depressive behaviors when left alone for prolonged periods. Vocal and Expressive: The breed communicates with a distinctive voice, often described as a “little goose honk.” They engage in vocal exchanges and will follow their humans from room to room. Highly Intelligent and Active: These cats display lifelong playfulness and investigative curiosity. When unsupervised, they often engage in high-energy behaviors such as climbing refrigerators, opening cabinets, or observing television with notable attentiveness. Emotionally Sensitive: Their strong attachment makes them vulnerable to environmental instability. Loss of a preferred human or significant routine changes can trigger noticeable emotional distress. As companion animals, Oriental Shorthairs are best suited for households that can provide consistent interaction, environmental enrichment, and emotional stability. 2. Breed Profile and Characteristics 2.1 Physical Characteristics Body Structure, Coat Type, and Color Variations The Oriental Shorthair conforms to the svelte, elongated body plan typical of Siamese-derived breeds. The body is long, refined, and flexible, with no tendency toward roundness. The coat is short, sleek, and fine, lying close to the skin and highlighting the breed’s angular physique. The breed is renowned for its extensive color genetics, with 281–300 documented coat and pattern combinations. (Cat Fanciers’ Association, n.d.; The International Cat Association, n.d.; Brearley, 2016). Commonly encountered colors include ebony, pure white, chestnut, and blue. Recognized pattern groups include solid, bi-color, tabby, smoke, and shaded variants. Distinctive Features Compared with Siamese-Related Breeds Although identical in body type to the Siamese, Balinese, and Oriental Longhair, the Oriental Shorthair differs primarily in: Coloration: The defining feature. Unlike the Siamese, Orientals do not exhibit pointed coloration and instead appear in a vast array of solid or patterned coats. Genotype: Orientals share the same structural genetics as the Siamese. Kittens of both breeds may occur within the same litter, separated only by coat phenotype. Eye Color: The preferred eye color in most Oriental Shorthairs is green, whereas Siamese-pointed colors have blue eyes. These distinctions maintain the breed’s identity while preserving Siamese type characteristics. 2.2 Behavioral Profile The Oriental Shorthair is an affectionate, alert, and highly communicative breed whose intelligence fuels constant exploration and problem-solving behaviors. Owners frequently describe them as emotionally expressive and endlessly curious. Their activity levels remain high throughout life, requiring ample vertical space, interactive toys, and consistent physical engagement. Socially, they form deep bonds with humans and typically integrate well with other pets, but prolonged isolation may trigger anxiety or depressive behaviors. Because of their intense mental and physical needs, environmental enrichment is essential: tall cat trees, puzzle feeders, training sessions, and supervised exploration all help maintain behavioral balance. Their natural attraction to warmth often draws them to sunlit windows, warm laps, or even beneath blankets. 3. Genetic Background and Hereditary Considerations 3.1 Breed Lineage The Oriental Shorthair descends directly from Siamese breeding programs and belongs to the Oriental Breed Group, along with the Siamese and Balinese. This shared lineage results in common genetic predispositions and similar breed-specific vulnerabilities. 3.2 Known Genetic Markers The Oriental Shorthair shares many hereditary conditions with its Siamese lineage, reflecting their close genetic relationship. Key inherited disorders documented in the breed include amyloidosis, a complex systemic disease involving amyloid deposition in organs such as the liver and thyroid, with both Mendelian and polygenic influences suggested. Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is another major concern, leading to gradual vision loss and now readily identifiable through genetic testing. Neurological and sensory conditions are also notable, including Hyperesthesia Syndrome, characterized by episodic agitation and overgrooming, as well as nystagmus, an involuntary ocular movement. Cardiovascular issues such as aortic stenosis and isolated reports of juvenile dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) have been described, alongside respiratory and anatomical tendencies such as asthma-like bronchial disease, dental irregularities linked to head structure, and occasional strabismus. Gastrointestinal vulnerabilities include megaesophagus, pica, and associated risks of obstruction. Additionally, the breed demonstrates increased susceptibility to oncological diseases, particularly lymphoma and mast cell neoplasia, reinforcing the importance of vigilant screening and responsible breeding practices. 3.3 Implications for Breeding and Selection Responsible Breeding Guidelines Breeders are encouraged to adopt structured genetic screening and maintain transparent communication regarding the health status of breeding lines. Given the presence of complex diseases such as amyloidosis, maintaining a broad genetic base is critical to prevent inbreeding depression. Reducing Disease Prevalence Through Genetic Testing PRA Screening: Routine testing helps identify carriers and avoid high-risk pairings. Monitoring High-Frequency Variants: The CEP290 variant affecting late-onset blindness has been identified in approximately 33 percent of surveyed Orientals, necessitating active management. (Wiseman et al., 2007; Hendricks et al., 2021; Embark Veterinary, 2023). Carrier Management: Recessive

Breed-related disease: Afghan Hound

Afghan hound, breed of dog developed as a hunter in the hill country of Afghanistan. It was once thought to have originated several thousand years ago in Egypt, but there is no evidence for this theory. It was brought to Europe in the late 19th century by British soldiers returning from the Indian-Afghan border wars. The Afghan hound hunts by sight and, in its native Afghanistan, has been used to pursue leopards and gazelles. The animal is adapted to rough country by the structure of its high, wide hipbones. A long-legged dog, the Afghan stands 25 to 27 inches (63.5 to 68.5 cm) high and weighs from 50 to 60 pounds (23 to 27 kg). It has floppy ears, a long topknot, and a long, silky coat of various but usually solid colours. The coat is especially heavy on the forequarters and hindquarters; the Afghan carries its slim tail in an upright curve. The Afghan’s appearance has been described as “aristocratic, with a farseeing expression.” The Afghan Hound is aloof and dignified, except when he’s being silly. Aloof doesn’t mean shy; he should never be afraid of people and is usually not aggressive toward them. He takes his time getting to know people outside his family. People who are fortunate enough to be allowed into his circle of friends will experience a dog with an exuberant nature and a wicked sense of humor. Afghans do everything to extremes. They are drama queens and food thieves, bossy and mischievous. They have a high prey drive, and although they may get along with the cats they were raised with, outdoor cats should fear for their lives when the Afghan springs into action. The Afghan is an independent thinker. He’s happy to do what you ask—as long as that’s what he wanted to do anyway. He’s highly intelligent and learns quickly, but he won’t always respond to your commands, er, requests. He’s thinking about it. Maybe he’ll do it later. Or not. This can make him frustrating to train and even more frustrating to compete with. Afghans have done well in sports such as agility and lure coursing, but only when their people have extreme patience, a never-ending sense of humor and a good command of positive reinforcement techniques to lure him into compliance. In this article we put some of the most important genetic predispositions for Afghan hounds Let’s get started: Heart Disease Afghan Hounds are prone to multiple types of heart disease, which can occur both early and later in life. We’ll listen for heart murmurs and abnormal heart rhythms when we examine your pet. When indicated, we’ll perform an annual heart health check, which may include X-rays, an ECG, or an echocardiogram, depending on your dog’s risk factors. Early detection of heart disease often allows us to treat with medication that usually prolongs your pet’s life for many years: Bone and Joint Problems A number of different musculoskeletal problems have been reported in Afghan Hounds. While it may seem overwhelming, each condition can be diagnosed and treated to prevent undue pain and suffering. With diligent observation at home and knowledge about the diseases that may affect your friend’s bones, joints, or muscles you will be able to take great care of him throughout his life. Anesthesia when it is time for a dental cleaning, surgery, or minor procedures such as suturing a wound, anesthesia is usually necessary. Afghan Hounds have a number of idiosyncrasies that can increase the risk of anesthesia. The good news is we have many years of experience with sighthounds and know to pay special attention to anesthetic problems such as: Hyperthermia (body temperature dangerously high) in nervous dogs Hypothermia (body temperature dangerously low) in dogs with a lean body conformation Prolonged recovery from some intravenous anesthetics and increased risks of drug interactions. Thyroid Problems Afghans are prone to a common condition called hypothyroidism in which the body doesn’t make enough thyroid hormone. Signs can include dry skin and coat, hair loss, susceptibility to other skin diseases, weight gain, fearfulness, aggression, or other behavioral changes. Chylothorax Afghans are more prone to an uncommon, but serious, condition called chylothorax where the chest cavity fills with a milky substance called chyle. In affected dogs, chyle accumulates in the chest cavity because of a faulty lymphatic duct called the thoracic duct. Chylothorax, while rare, is life threatening and requires immediate medical attention. Often surgery is need to help manage the disease. Watch for difficulty breathing, coughing or lethargy as these may be the first signs of this disease. Sources: https://wovh.com/client-resources/breed-info/afghan-hound/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/afghan-hound#personality Photo credit: https://www.yourpurebredpuppy.com/health/afghanhounds.html http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/afghan-hound#personality

Breed-related disease: Russian Blue Cat

Although the Russian blue’s exact origins are not known for certain, but the Russian Blue cat was originally known as the Archangel Cat because it was said to have arrived in Europe aboard ships from the Russian port of that name (Arkhangel’sk). It has also been known as the Spanish Cat and the Maltese cat, particularly in the US where the latter name persisted until the beginning of the century. The cat was favored by royals and preferred by the Russian czars. The Russian Blue cat is medium to large in size with an elegant, graceful body and long, slim legs. The cat walks as if on tip-toes. The head is wedged shaped with prominent whisker pads and large ears. The vivid green eyes are set wide apart and are almond shaped. The coat is double with a very dense undercoat and feels fine, short and soft. In texture the coat of the Russian Blue cat is very different from any other breed and is the truest measure of the breed. Although named the Russian Blue, black and white Russian cats do sometimes appear. In the most popular blue variety, the coat colour is a clear even blue with a silvery sheen. The Russian blue is a sweet-tempered, loyal cat who will follow her owner everywhere, so don’t be surprised if she greets you at the front door! While she has a tendency to attach to one pet parent in particular, she demonstrates affection with her whole family and demands it in return. It’s said that Russian blues train their owners rather than the owners training them, a legend that’s been proven true time and again. They are very social creatures but also enjoy alone time and will actively seek a quiet, private nook in which to sleep. They don’t mind too much if you’re away at work all day, but they do require a lot of playtime when you are home. Russian blues tend to shy away from visitors and may hide during large gatherings. As we know you care for your pet, below, we listed the few of the most common diseases in the animal Weight related problems. The Russian Blue cat really enjoys its food and it may continue to eat as much as it chooses. So, it’s best to limit the amount of food that the cat enjoys to ensure a healthy diet and to combat any weight related illnesses . Progressive retinal atrophy refers to a family of eye conditions which cause the retina’s gradual deterioration. Night vision is lost in the early stages of the disease, and day vision is lost as the disease progresses. Many cats adapt to the loss of vision well, as long as their environment stays the same. Polycystic kidney disease. PKD is a condition that is inherited and symptoms can start to show at a young age. Polycystic Kidney Disease causes cysts of fluid to form in the kidneys, obstructing them from functioning properly. It can cause chronic renal failure if not detected . Look for symptoms like poor appetite, vomiting, drinking excessively, frequent urination, lethargy and depression. Ultrasounds are the best way to diagnose the disease, and some cats can be treated with diet, medication and hormone therapy. Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is a disease that can affect the bladder and urethra of cats. Cats with FLUTD present with pain and have difficulty urinating. They also urinate more often and blood may be visible in the urine. Cats may lick their genital area excessively and sometimes randomly urinate around the house. These symptoms may re-occur through a cat’s life so it’s best to discuss things with a vet. Source: https://www.purina.co.uk/cats/cat-breeds/library/russian-blue https://bowwowinsurance.com.au/cats/cat-breeds/russian-blue/ Picture credit 1 Picture credit 2

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog

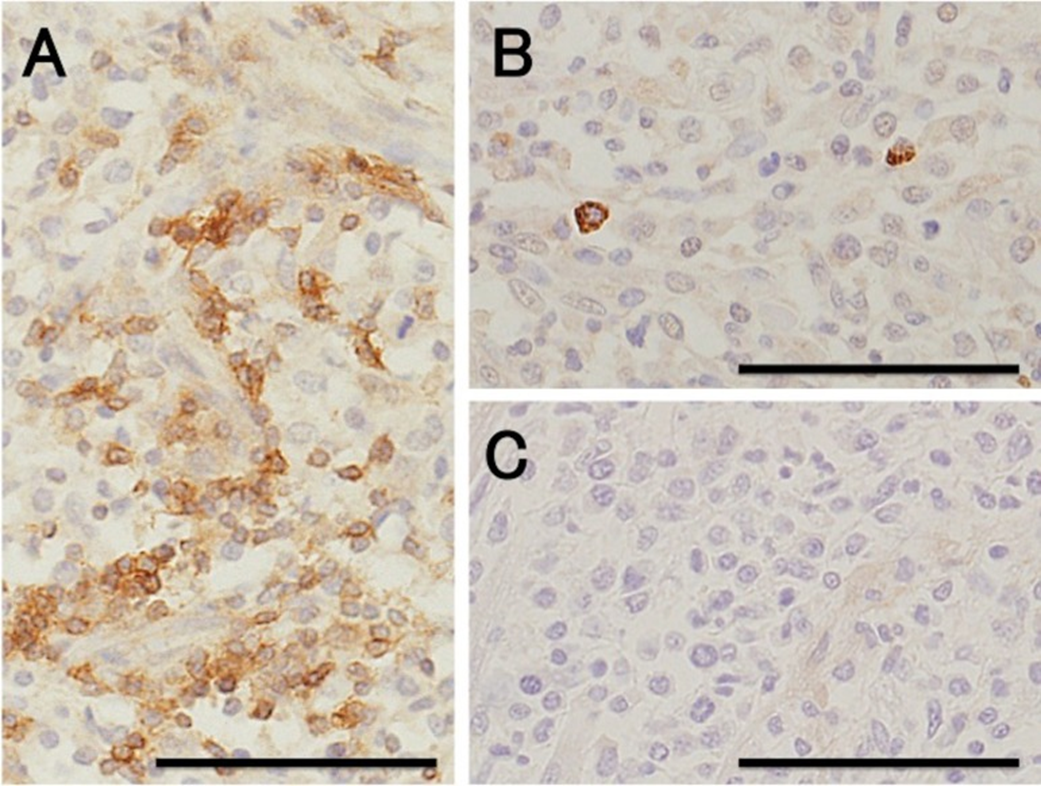

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog Robert Lo, Ph.D, D.V.M Original: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6261812/ Canine lymphoma usually appears in multicentric, alimentary, mediastinal, and cutaneous forms, but rarely affects only heart. This case reports a uncommon primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) of a 10-week-old miniature dachshund. The dog clinically showed acute onset of weakness. Electrocardiography indicated sustained ventricular tachycardia, and thoracic and abdominal radiography revealed pleural and peritoneal effusion. Echocardiography revealed severely hypokinetic left and right ventricles. After failure of treatment, the dog died about 1 hr after admission and underwent autopsy. Gross examination of a longitudinal section through the entire heart revealed poorly demarcated focal or patchy areas of grayish-white tissue infiltrating extensively into the myocardium. Histologically, these lesions were consistent with infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the diagnosis of PCL of T-cell origin. There have been no previous reports of such young dogs with PCL. Fig. 1. Six lead electrocardiographic tracings from the 10-week-old dog, showing monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, rate 360 beats per minute, almost regular (bipolar standard limb leads; 50 mm/sec). Fig. 2. Formalin-fixed heart transected along the long axis, showing extensive infiltration of grayish-white neoplastic tissue into the myocardium of the entire heart. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. Scale: 1 mm. Fig. 3. (A) Microscopic section taken from the ventricular septum, showing marked infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells in the myocardium. Sheets of neoplastic round cells separate individual muscle fibers. HE. Bar: 50 µm. (B) The outlined square area in A is shown at higher magnification. HE. Bar: 20 µm. Fig. 4. Immunohistochemical labeling of the neoplastic lymphoid cells. Hematoxylin counterstain. Bar: 50 µm. (A) A large number of neoplastic cells stain positively for CD3. (B) Fewer neoplastic cells stain positively for CD79α. (C) All the neoplastic cells are negative for CD20.

What are Feline Injection-Site Sarcomas (FISS)?

What are Feline Injection-Site Sarcomas (FISS)? Maigan Espinili Maruquin I. Characteristics / Epidemiology The feline injection-site sarcomas (FISS) were first reported on 1991 (Hendrick and Goldschmidt 1991). With the implementation of stricter vaccination and development of vaccines for rabies and FeLV, the increased incidence of vaccine reactions was recognized (Hendrick and Dunagan 1991, Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015, Saba 2017). With this, recommendations were to use the term ‘vaccine-associated sarcomas’, however, studies show that aside from vaccines are other non-vaccinal injectables in the subcutis or muscle can also cause chronic inflammatory response which led to reclassification as ‘feline injection-site sarcomas’ (FiSSs) (Martano, Morello et al. 2011, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). The FISS develops in 1–10 of every 10,000 vaccinated cats wherein malignant skin tumors of mesenchymal origin develops (Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). It has been described as secondary to inflammation in different organs like eye (PEIFFER, MONTICELLO et al. 1988), uterus (Jelínek 2003) and muscle or skin after placement of non-absorbable suture or microchips (Buracco, Martano et al. 2002) (Bowlt 2015). Between three months to 10 years after vaccination, the development of FISS can occur (Hendrick, Shofer et al. 1994, McEntee and Page 2001) (Esplin, D. G., et al., 1993). Whereas, a study reported that the younger cats developed tumor at the vaccination site as compared to the older ones with similar tumors in other body areas with bimodal distribution of age with a peak at 6–7 years and a second at 10–11 years (Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Martano, Morello et al. 2011). Fig. 01. Saba, C. F. 2017 shows the occurrence of FISS. (https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S116556) II. Pathogenesis / Clinical Signs After investigations, the hypothesis suggests that secondary to chronic and inflammatory response to vaccine or injection, having ultimate malignant transformation of surrounding fibroblasts and myofibroblasts triggers the tumors (Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015, Saba 2017)( Hendrick MJ., 1999). Fig. 02. (Cecco, B.S., et al., 2019) The sites where FISS occurs (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2019.08.009) Reports show significant correlation between the rabies and/ or FeLV vaccinations in the development of FISS (Hendrick, Goldschmidt et al. 1992, Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Hendrick, Shofer et al. 1994). Despite many causes are associated with what triggers the tumor, higher risks are seemed to be coming from vaccines, specifically adjuvanted (Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). Discovered were traces of adjuvants in the inflammatory reaction and later in histological sections (Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). Particles of grey- brown material in the necrotic centre and within the cytoplasm of macrophages were reported consistent with an inflammatory reaction (Hendrick and Dunagan 1991, Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Martano, Morello et al. 2011). The infiltrates reported includes macrophages often having cytoplasmic material, giant cells, lymphocytes and mixed neutrophils and eosinophils. Further, identified in the tumors were cytokines, growth factors and mutations in tumor suppressor genes (Ladlow 2013, Carneiro, de Queiroz et al. 2018). While fibrosarcoma is commonly diagnosed, some histological types were also reported to include: malignant fibrous histiocytoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, myxosarcoma, liposarcoma, nerve sheath tumor, poorly differentiated sarcomas, and extraskeletal osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma (Esplin, McGill et al. 1993, Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hershey, Sorenmo et al. 2000, Dillon, Mauldin et al. 2005, Saba 2017). According to Saba. C, 2017, any sarcoma that develops within the vicinity of vaccination or injection site should be considered an FISS and thus, should be treated aggressively. While tumors are invasive and variable in size, Martano M.E., et al, 2011 reported that large sized may be due to rapid growth. On the other hand, there could also be delayed in appearance due to its interscapular or deep location (Bowlt 2015). The mass can also be mobile or intensely adherent to the underlying tissue which is usually not painful, but solid and may be cystic (Bowlt 2015). These tumors that develop commonly in sites of injection can reach several centimetres in diameter within a few weeks (Martano, Morello et al. 2011). Since not all cats develop this tumor after vaccination, suggestions are due to genetic predisposition, with higher case of FISS occurrence in siblings of affected cats. Further, some cats may develop more than one FiSS (Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). III. Staging / Diagnosis To properly react with the tumor, proper staging shall be performed. Once a histological diagnosis has been confirmed (Bowlt 2015), it requires complete blood count, a serum biochemical panel, urinalysis, 3-view thoracic radiography, lymph node examination by palpation, and ultrasonography of the abdominal cavity and cytology when applicable (Séguin 2002, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Abdominal ultrasound may be required, depending on the location of the tumor. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lesion and the thorax is required to see the actual size and evaluate the extent of the tumor (Cronin, Page et al. 1998, McEntee and Page 2001, Martano, Morello et al. 2011, Rousset, Holmes et al. 2013, Travetti, di Giancamillo et al. 2013, Saba 2017, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Thoracic radiography is then performed to exclude metastatic deseases, which has 10- 24% chances (Saba 2017, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Whereas, there is as high as 45% for the recurrence rate even after performing surgical excision (Cronin, Page et al. 1998) IV. Treatment Considering the possibility of misdiagnosing the tumor as a granuloma from small tissue samples, and the fact that these can be heterogeneous, incisional biopsy can be done at sites that can be easily excised (Martano, Morello et al. 2011). The indications for a biopsy are based in 3-2-1 rule (Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force, 2005; Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force guidelines, 1999; (Morrison and Starr 2001). This incisional biopsy is strongly recommended for masses that has persisted for >3 months, is >2 cm, and/or is growing over the course of 1 month post injection in the site (Saba 2017). Radical surgery or wide excision may be recommended. Surgery will be