Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome

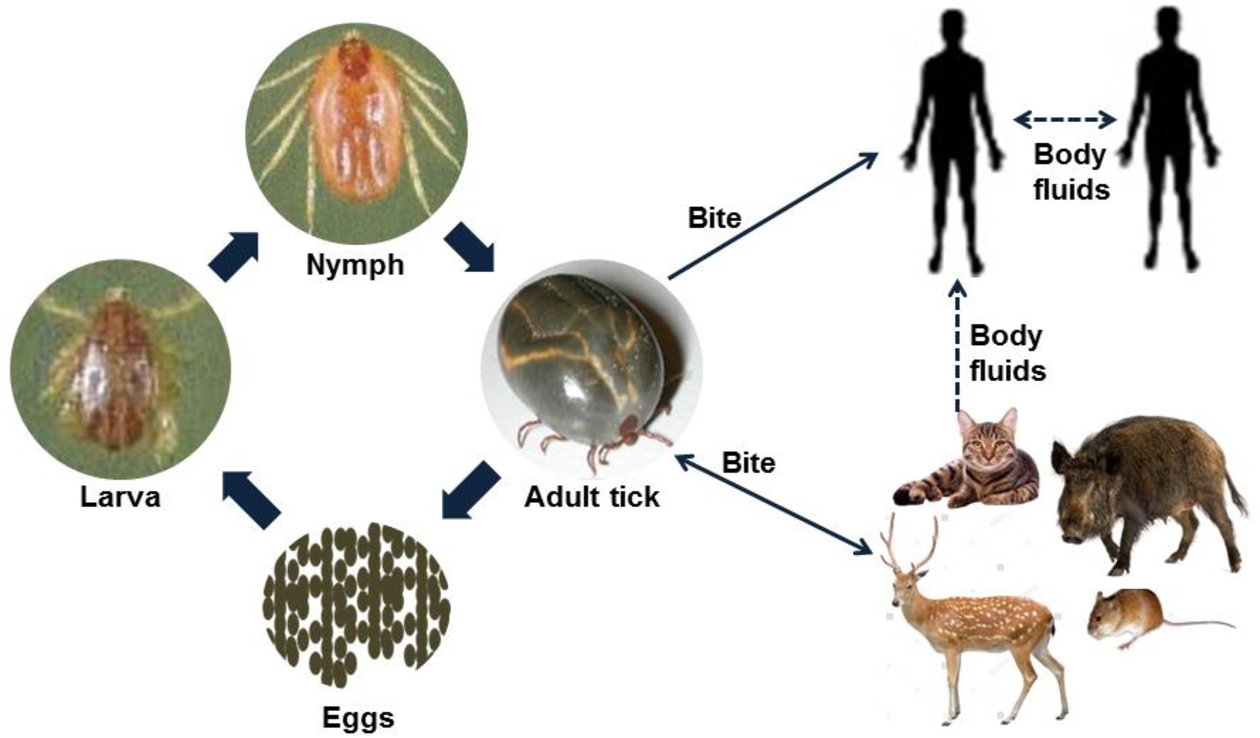

Bioguard Corporation Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious disease that was first reported in China in 2011. It is caused by the Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome virus (SFTSV) and is transmitted to humans and animals through the bite of an infected tick. The main clinical symptoms of SFTS include fever, […]

Lyme Disease in Dogs

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is triggered by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which belongs to the spirochete class, characterized by its worm-like, spiral shape within the genus Borrelia. This bacterium is spread to both dogs and humans through the bite of an infected black legged tick, also known as the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). The […]