Lyme Disease in Dogs

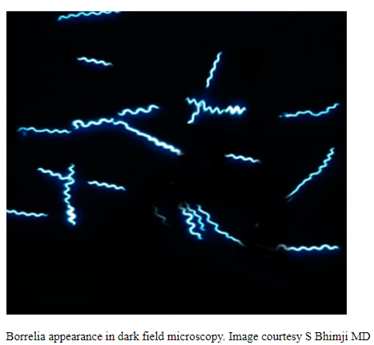

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is triggered by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which belongs to the spirochete class, characterized by its worm-like, spiral shape within the genus Borrelia. This bacterium is spread to both dogs and humans through the bite of an infected black legged tick, also known as the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). The […]

Canine Lyme Disease

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is a disease caused by the bacterium Borellia burdorgferi; a worm like, spiral-shape bacterium of spirochete class in the genus Borellia. The bacterium B. burgdorferi is transmitted through a bite of infected blacklegged tick or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) to dogs and humans[1]. Different life-stage of I. scapularis ticks emerge at different […]