Factor VII Deficiency in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Canine Factor VII (FVII) deficiency is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that leads to a mild to moderate blood clotting problem in affected dogs. Puppies with the condition may exhibit symptoms such as nosebleeds (epistaxis) and gum bleeding, while adult dogs are more prone to bruising and skin issues like dermatitis. Though bleeding […]

Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD) is a hereditary genetic disorder that impairs the ability of red blood cells to metabolize properly. This defect leads to the destruction of red blood cells, resulting in severe hemolytic anemia. Affected animals can die from complications such as severe anemia and liver failure. The condition typically manifests between […]

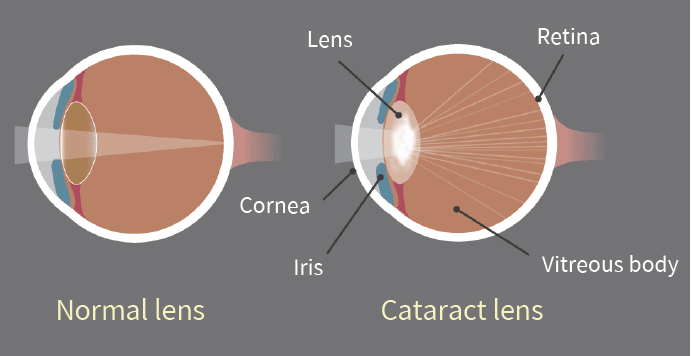

Juvenile Hereditary Cataracts in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Canine juvenile cataract (JHC) is a hereditary form of cataract characterized by cloudiness and degeneration of the lens in the eye. This condition prevents light and images from passing through the lens to the retina, impairing the dog’s vision and eventually leading to blindness. Affected dogs may exhibit symptoms such as bumping into […]

Cryptosporidiosis

Bioguard Corporation Cryptosporidiosis is an illness you get from the parasite Cryptosporidium. It causes watery diarrhea and other gastrointestinal (gut) symptoms. In addition to stomach infection, this parasite can infect the respiratory system causing a cough and/or problems breathing. The family Cryptosporididae belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa characterized by an anterior (or apical) polar complex […]

Lyme Disease in Dogs

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is triggered by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which belongs to the spirochete class, characterized by its worm-like, spiral shape within the genus Borrelia. This bacterium is spread to both dogs and humans through the bite of an infected black legged tick, also known as the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). The […]