Canine Lyme Disease

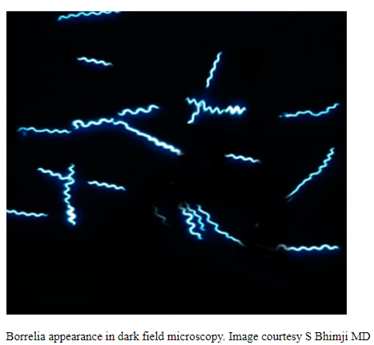

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is a disease caused by the bacterium Borellia burdorgferi; a worm like, spiral-shape bacterium of spirochete class in the genus Borellia. The bacterium B. burgdorferi is transmitted through a bite of infected blacklegged tick or deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) to dogs and humans[1]. Different life-stage of I. scapularis ticks emerge at different times of the year (varies according to geographic location), giving a seasonality to Lyme disease transmission dynamics. It appears primarily in specific areas including the southern New England states; eastern Mid-Atlantic states; the upper Midwest, particularly Wisconsin and Minnesota; and on the West Coast, particularly northern California in the United States. It is also present in Europe and Asia[7]. Most of the areas where to find them are in forest or grassy, wooded, marshy areas near rivers, lakes or ocean, and are common in homes and buildings in secluded or rural areas. In Canada, there 2 types of blacklegged or deer tick that can spread Lyme disease. The blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the blacklegged (Ixodes pacificus) [3] . Dogs tend to be bitten by infected I. scapularis adults, which are most active in the cooler early spring and late fall months [2]. An adult female tick is rarely (if ever) transmitted the B. burgdorferi to her offspring. Ticks most commonly become infected as juveniles after a bloodmeal on an infected wildlife host (most commonly rodents). Because ticks typically feed only one time per life stage, the next opportunity for B. burgdorferi transmission is during the next bloodmeal in the tick’s next life stage[2]. Typically, Lyme disease symptoms will take a couple of months or more to appear (2-5 months) after getting infected [8]. Symptomatically, Lyme disease can be difficult to distinguish from anaplasmosis because the signs of the diseases are very similar, and they occur in essentially the same areas of the country. Lyme disease is diagnosed through a blood test that shows whether an animal has been exposed to the bacterium[11]. Common symptoms that will appear are: Lameness: An inability to use one or more limbs is one of the most common symptoms of Lyme disease in dogs. Swollen lymph nodes: found in the neck, chest, armpits, groin, and behind the knees, are typically the first to show swelling. Lymph node swelling indicates an immune response triggered to fight the disease. Joint swelling: Swollen joints, stiff walking, or avoidance to touch may be other signs of the disease. Fatigue: Dogs with Lyme disease may also exhibit flu-like symptoms of low energy and lethargy. Loss of appetite: Losing interest in eating, especially if it leads to weight loss, is another sign that a dog may have Lyme. Fever: In addition to the above symptoms, a dog may have a fever caused by the Lyme disease infection. In rare cases, if Lyme disease is left untreated it can lead to damage in the kidneys, nervous system, and heart. Lyme disease affecting the kidneys is the second most common syndrome in dogs and is generally fatal. Facial paralysis and seizure disorders have been reported in the disease form affecting the nervous system. The form of the disease that affects the heart is rare. [10]. The most commonly used to diagnose Lyme disease in dogs are the serologic assays. Although some laboratories still use traditional serologic methods (e.g., whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunofluorescence assay), these assays have largely been replaced by serologic assays that detect host antibodies to specific B. burgdorferi proteins. These assays are qualitative, providing a yes/no answer regarding B. burgdorferi serostatus[3]. Treatment is generally recommended for seropositive dogs that display clinical signs of Lyme disease or are asymptomatic but have evidence of protein-losing nephropathy[4]. Most frequently antibiotics used to treat Lyme disease in dogs are doxyclycline and monicycline, at a dosage of 10mg/kg PO q12h to q24h for 30 days [2][5]. Amoxicillin and erythromycin are other antibiotics that can be used for treating the disease. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (carprofen or deracoxib) may also be given to the patient [6]. A possible complications may occur when treating Lyme disease. Some dogs who take antibiotics can develop loss of appetite, vomiting and diarrhea. Once infected, a dog will always have the bacteria that cause Lyme disease in his or her body. Therefore, relapses are possible; lookout for unexplained fever, swollen lymph nodes, and/or lameness. A small percentage of dogs develop kidney failure as a result of Lyme disease. Clinical signs include vomiting, weight loss, poor appetite, lethargy, increased thirst and urination, and abnormal accumulations of fluid within the body. [6] The best way to protect from Lyme disease is to use tick-preventive products year-round. Several safe and effective commercial parasiticides are available for tick control on dogs and cats, including systemics (isoxazolines), topicals (permethrin, fipronil), and collars. Another effective strategy is vaccination. Other prevention strategies include reducing exposure to ticks and avoiding areas with ticks [2]. References [1] Lyme Disease Diagnostic Market – Growth, Trends, COVID-19 Impact, and Forecasts (2022 – 2027), MOdor Intelligence, January 202 [2] Lyme Disease in Dogs: Signs and Prevention, Kathryn E. Reif, MSPH, PhD.,April 2020, https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/parasitology/lyme-disease/ [3] Lyme Disease, IPAC (https://ipac-canada.org/lyme-disease.php) [4] / Littman MP, Gerber B, Goldstein RE, et al. ACVIM consensus update on Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2018;32(3):887-903. [5] Mullegger RR. Dermatological manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004 Sep-Oct;14(5):296-309. PMID: 15358567 [6] How to Treat Lyme Disease in Dogs, Jennifer Coates, DVM, December 2014, PETMD (https://www.petmd.com) [7] Lebech AM. Polymerase chain reaction in diagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi infections and studies on taxonomic classification. APMIS Suppl. 2002;(105):1-40. PMID: 11985118 [8] Could Your Dog Have Lyme Disease? How to Recognize the Symptoms and Get Treatment, Lavanya Sunkara , July 2022, GoodRx Health [9] Everything You Need To Know About Lyme Disease In Dogs, Kimberly Alt, July 2022, Canine Journal [10] Lyme Disease (Lyme Borreliosis) in Dogs, Reinhard K. Straubinger, DrMedVetHabil, PhD, Institute for Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Department of Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, LMU, October 2022 [11] Lyme disease: A pet owner’s guide, American Veterinary Medical Association