WHAT DOES “ANTIBIOTIC RANK” MEANS?

The use of antibiotics is critical to maintaining both human and animal health, ensuring food safety, and preventing the spread of zoonotic diseases. However, concerns about antibiotic resistance have prompted the need to rank veterinary antibiotics based on their importance, usage, and associated risks. This ranking or categorization serves as a tool to support veterinarians […]

Understanding Antibiotic Classifications: A Comprehensive Guide

Antibiotics are essential tools in modern medicine, used to combat bacterial infections that could otherwise lead to severe health issues or even death. To use these powerful drugs effectively, it’s crucial to understand the different classifications of antibiotics, which are based on their chemical structure, mechanism of action, and spectrum of activity. This article explores […]

Fowl Pox

Bioguard Corporation Fowl pox is a slow-spreading viral disease affecting chickens, turkeys, and various other birds. It is characterized by proliferative skin lesions that develop into thick scabs (cutaneous form) and lesions in the upper respiratory and digestive tracts (diphtheritic form). A presumptive diagnosis can be made in the field based on distinctive skin lesions, […]

Factor VII Deficiency in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Canine Factor VII (FVII) deficiency is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that leads to a mild to moderate blood clotting problem in affected dogs. Puppies with the condition may exhibit symptoms such as nosebleeds (epistaxis) and gum bleeding, while adult dogs are more prone to bruising and skin issues like dermatitis. Though bleeding […]

Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKD) is a hereditary genetic disorder that impairs the ability of red blood cells to metabolize properly. This defect leads to the destruction of red blood cells, resulting in severe hemolytic anemia. Affected animals can die from complications such as severe anemia and liver failure. The condition typically manifests between […]

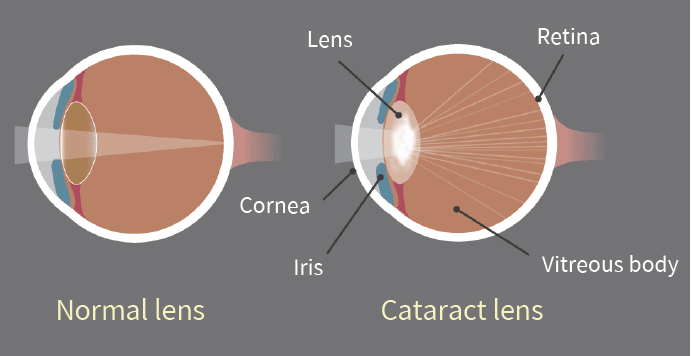

Juvenile Hereditary Cataracts in Dogs

Bioguard Corporation Canine juvenile cataract (JHC) is a hereditary form of cataract characterized by cloudiness and degeneration of the lens in the eye. This condition prevents light and images from passing through the lens to the retina, impairing the dog’s vision and eventually leading to blindness. Affected dogs may exhibit symptoms such as bumping into […]

Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Cats

Bioguard Corporation Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) an autosomally recessive inherited neurodegenerative disorder seen in Maine Coon cats. The disease is characterized by weakness and atrophy in muscles due to loss of motor neurons that control muscle movement. Affected cats first show signs of disease around 3–4 months of age. Clinical signs include tremors, abnormal posture, […]

Polycystic Kidney Disease in Cats

Bioguard Corporation Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a chromosomally dominant genetic disorder; it can occur in humans, cats, dogs, and other animals. In the renal cortex and medulla, there are cysts of various sizes and fluid-filled, so it is commonly known as the bubble kidney. Cysts increase in size and number over time, replacing kidney […]

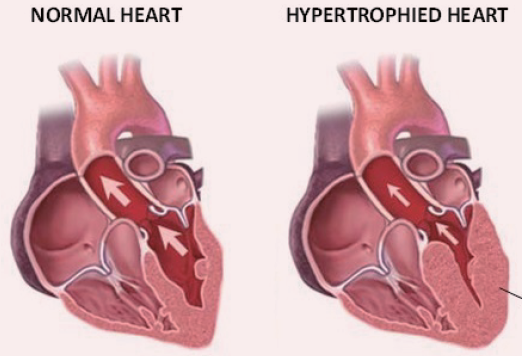

Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Bioguard Corporation Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary, familial, and hereditary heart condition, and it is the most common heart disease in cats. Its key characteristic is primary concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (thickening of the heart wall), which occurs without pressure overload (such as from aortic stenosis), hormone stimulation (like in hyperthyroidism or acromegaly), myocardial […]

Dog Frostbite: Canine Degenerative Spinal Neuropathy

Bioguard Corporation Degenerative Myelopathy, DM is a progressive chronic degenerative disease of the central nervous system, which is a recessive genetic disease that mainly occurs in the spinal nerve, similar to human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It is known as lou gehrig’s disease. The age of onset of dogs is between 9 and 11 years old, […]