Breed-related disease: Afghan Hound

Afghan hound, breed of dog developed as a hunter in the hill country of Afghanistan. It was once thought to have originated several thousand years ago in Egypt, but there is no evidence for this theory. It was brought to Europe in the late 19th century by British soldiers returning from the Indian-Afghan border wars. The Afghan hound hunts by sight and, in its native Afghanistan, has been used to pursue leopards and gazelles. The animal is adapted to rough country by the structure of its high, wide hipbones. A long-legged dog, the Afghan stands 25 to 27 inches (63.5 to 68.5 cm) high and weighs from 50 to 60 pounds (23 to 27 kg). It has floppy ears, a long topknot, and a long, silky coat of various but usually solid colours. The coat is especially heavy on the forequarters and hindquarters; the Afghan carries its slim tail in an upright curve. The Afghan’s appearance has been described as “aristocratic, with a farseeing expression.” The Afghan Hound is aloof and dignified, except when he’s being silly. Aloof doesn’t mean shy; he should never be afraid of people and is usually not aggressive toward them. He takes his time getting to know people outside his family. People who are fortunate enough to be allowed into his circle of friends will experience a dog with an exuberant nature and a wicked sense of humor. Afghans do everything to extremes. They are drama queens and food thieves, bossy and mischievous. They have a high prey drive, and although they may get along with the cats they were raised with, outdoor cats should fear for their lives when the Afghan springs into action. The Afghan is an independent thinker. He’s happy to do what you ask—as long as that’s what he wanted to do anyway. He’s highly intelligent and learns quickly, but he won’t always respond to your commands, er, requests. He’s thinking about it. Maybe he’ll do it later. Or not. This can make him frustrating to train and even more frustrating to compete with. Afghans have done well in sports such as agility and lure coursing, but only when their people have extreme patience, a never-ending sense of humor and a good command of positive reinforcement techniques to lure him into compliance. In this article we put some of the most important genetic predispositions for Afghan hounds Let’s get started: Heart Disease Afghan Hounds are prone to multiple types of heart disease, which can occur both early and later in life. We’ll listen for heart murmurs and abnormal heart rhythms when we examine your pet. When indicated, we’ll perform an annual heart health check, which may include X-rays, an ECG, or an echocardiogram, depending on your dog’s risk factors. Early detection of heart disease often allows us to treat with medication that usually prolongs your pet’s life for many years: Bone and Joint Problems A number of different musculoskeletal problems have been reported in Afghan Hounds. While it may seem overwhelming, each condition can be diagnosed and treated to prevent undue pain and suffering. With diligent observation at home and knowledge about the diseases that may affect your friend’s bones, joints, or muscles you will be able to take great care of him throughout his life. Anesthesia when it is time for a dental cleaning, surgery, or minor procedures such as suturing a wound, anesthesia is usually necessary. Afghan Hounds have a number of idiosyncrasies that can increase the risk of anesthesia. The good news is we have many years of experience with sighthounds and know to pay special attention to anesthetic problems such as: Hyperthermia (body temperature dangerously high) in nervous dogs Hypothermia (body temperature dangerously low) in dogs with a lean body conformation Prolonged recovery from some intravenous anesthetics and increased risks of drug interactions. Thyroid Problems Afghans are prone to a common condition called hypothyroidism in which the body doesn’t make enough thyroid hormone. Signs can include dry skin and coat, hair loss, susceptibility to other skin diseases, weight gain, fearfulness, aggression, or other behavioral changes. Chylothorax Afghans are more prone to an uncommon, but serious, condition called chylothorax where the chest cavity fills with a milky substance called chyle. In affected dogs, chyle accumulates in the chest cavity because of a faulty lymphatic duct called the thoracic duct. Chylothorax, while rare, is life threatening and requires immediate medical attention. Often surgery is need to help manage the disease. Watch for difficulty breathing, coughing or lethargy as these may be the first signs of this disease. Sources: https://wovh.com/client-resources/breed-info/afghan-hound/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/afghan-hound#personality Photo credit: https://www.yourpurebredpuppy.com/health/afghanhounds.html http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/afghan-hound#personality

Breed-related disease: Russian Blue Cat

Although the Russian blue’s exact origins are not known for certain, but the Russian Blue cat was originally known as the Archangel Cat because it was said to have arrived in Europe aboard ships from the Russian port of that name (Arkhangel’sk). It has also been known as the Spanish Cat and the Maltese cat, particularly in the US where the latter name persisted until the beginning of the century. The cat was favored by royals and preferred by the Russian czars. The Russian Blue cat is medium to large in size with an elegant, graceful body and long, slim legs. The cat walks as if on tip-toes. The head is wedged shaped with prominent whisker pads and large ears. The vivid green eyes are set wide apart and are almond shaped. The coat is double with a very dense undercoat and feels fine, short and soft. In texture the coat of the Russian Blue cat is very different from any other breed and is the truest measure of the breed. Although named the Russian Blue, black and white Russian cats do sometimes appear. In the most popular blue variety, the coat colour is a clear even blue with a silvery sheen. The Russian blue is a sweet-tempered, loyal cat who will follow her owner everywhere, so don’t be surprised if she greets you at the front door! While she has a tendency to attach to one pet parent in particular, she demonstrates affection with her whole family and demands it in return. It’s said that Russian blues train their owners rather than the owners training them, a legend that’s been proven true time and again. They are very social creatures but also enjoy alone time and will actively seek a quiet, private nook in which to sleep. They don’t mind too much if you’re away at work all day, but they do require a lot of playtime when you are home. Russian blues tend to shy away from visitors and may hide during large gatherings. As we know you care for your pet, below, we listed the few of the most common diseases in the animal Weight related problems. The Russian Blue cat really enjoys its food and it may continue to eat as much as it chooses. So, it’s best to limit the amount of food that the cat enjoys to ensure a healthy diet and to combat any weight related illnesses . Progressive retinal atrophy refers to a family of eye conditions which cause the retina’s gradual deterioration. Night vision is lost in the early stages of the disease, and day vision is lost as the disease progresses. Many cats adapt to the loss of vision well, as long as their environment stays the same. Polycystic kidney disease. PKD is a condition that is inherited and symptoms can start to show at a young age. Polycystic Kidney Disease causes cysts of fluid to form in the kidneys, obstructing them from functioning properly. It can cause chronic renal failure if not detected . Look for symptoms like poor appetite, vomiting, drinking excessively, frequent urination, lethargy and depression. Ultrasounds are the best way to diagnose the disease, and some cats can be treated with diet, medication and hormone therapy. Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is a disease that can affect the bladder and urethra of cats. Cats with FLUTD present with pain and have difficulty urinating. They also urinate more often and blood may be visible in the urine. Cats may lick their genital area excessively and sometimes randomly urinate around the house. These symptoms may re-occur through a cat’s life so it’s best to discuss things with a vet. Source: https://www.purina.co.uk/cats/cat-breeds/library/russian-blue https://bowwowinsurance.com.au/cats/cat-breeds/russian-blue/ Picture credit 1 Picture credit 2

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog

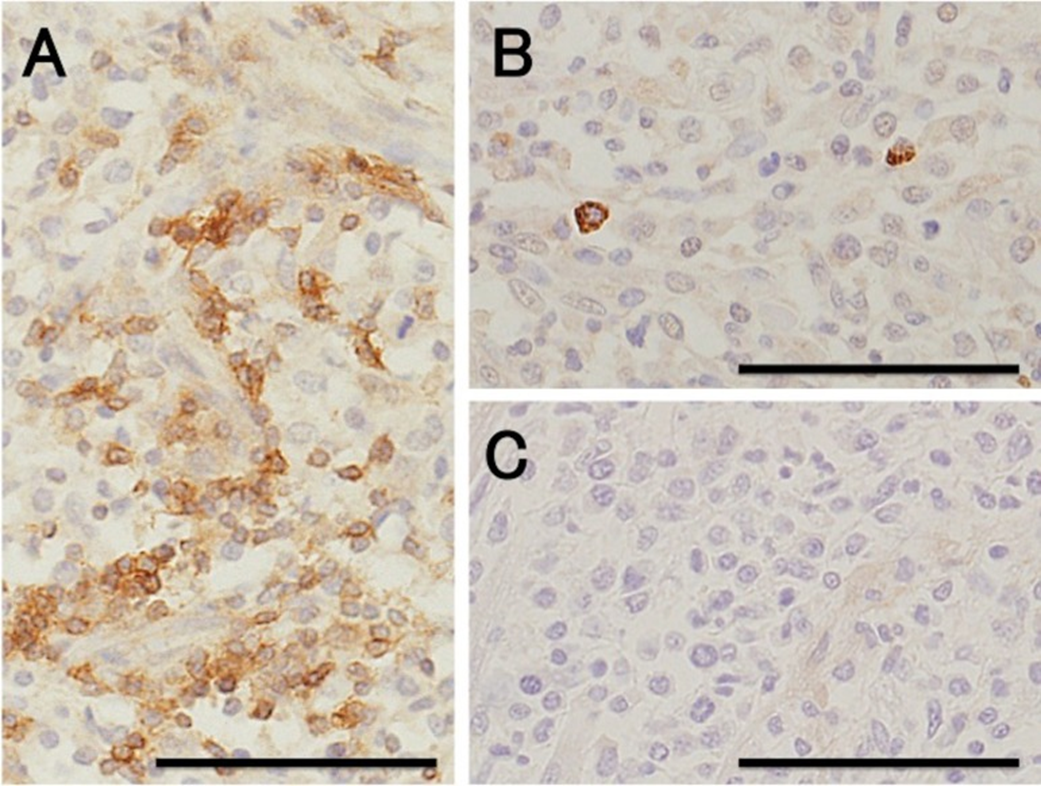

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog Robert Lo, Ph.D, D.V.M Original: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6261812/ Canine lymphoma usually appears in multicentric, alimentary, mediastinal, and cutaneous forms, but rarely affects only heart. This case reports a uncommon primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) of a 10-week-old miniature dachshund. The dog clinically showed acute onset of weakness. Electrocardiography indicated sustained ventricular tachycardia, and thoracic and abdominal radiography revealed pleural and peritoneal effusion. Echocardiography revealed severely hypokinetic left and right ventricles. After failure of treatment, the dog died about 1 hr after admission and underwent autopsy. Gross examination of a longitudinal section through the entire heart revealed poorly demarcated focal or patchy areas of grayish-white tissue infiltrating extensively into the myocardium. Histologically, these lesions were consistent with infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the diagnosis of PCL of T-cell origin. There have been no previous reports of such young dogs with PCL. Fig. 1. Six lead electrocardiographic tracings from the 10-week-old dog, showing monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, rate 360 beats per minute, almost regular (bipolar standard limb leads; 50 mm/sec). Fig. 2. Formalin-fixed heart transected along the long axis, showing extensive infiltration of grayish-white neoplastic tissue into the myocardium of the entire heart. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. Scale: 1 mm. Fig. 3. (A) Microscopic section taken from the ventricular septum, showing marked infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells in the myocardium. Sheets of neoplastic round cells separate individual muscle fibers. HE. Bar: 50 µm. (B) The outlined square area in A is shown at higher magnification. HE. Bar: 20 µm. Fig. 4. Immunohistochemical labeling of the neoplastic lymphoid cells. Hematoxylin counterstain. Bar: 50 µm. (A) A large number of neoplastic cells stain positively for CD3. (B) Fewer neoplastic cells stain positively for CD79α. (C) All the neoplastic cells are negative for CD20.

What are Feline Injection-Site Sarcomas (FISS)?

What are Feline Injection-Site Sarcomas (FISS)? Maigan Espinili Maruquin I. Characteristics / Epidemiology The feline injection-site sarcomas (FISS) were first reported on 1991 (Hendrick and Goldschmidt 1991). With the implementation of stricter vaccination and development of vaccines for rabies and FeLV, the increased incidence of vaccine reactions was recognized (Hendrick and Dunagan 1991, Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015, Saba 2017). With this, recommendations were to use the term ‘vaccine-associated sarcomas’, however, studies show that aside from vaccines are other non-vaccinal injectables in the subcutis or muscle can also cause chronic inflammatory response which led to reclassification as ‘feline injection-site sarcomas’ (FiSSs) (Martano, Morello et al. 2011, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). The FISS develops in 1–10 of every 10,000 vaccinated cats wherein malignant skin tumors of mesenchymal origin develops (Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). It has been described as secondary to inflammation in different organs like eye (PEIFFER, MONTICELLO et al. 1988), uterus (Jelínek 2003) and muscle or skin after placement of non-absorbable suture or microchips (Buracco, Martano et al. 2002) (Bowlt 2015). Between three months to 10 years after vaccination, the development of FISS can occur (Hendrick, Shofer et al. 1994, McEntee and Page 2001) (Esplin, D. G., et al., 1993). Whereas, a study reported that the younger cats developed tumor at the vaccination site as compared to the older ones with similar tumors in other body areas with bimodal distribution of age with a peak at 6–7 years and a second at 10–11 years (Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Martano, Morello et al. 2011). Fig. 01. Saba, C. F. 2017 shows the occurrence of FISS. (https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S116556) II. Pathogenesis / Clinical Signs After investigations, the hypothesis suggests that secondary to chronic and inflammatory response to vaccine or injection, having ultimate malignant transformation of surrounding fibroblasts and myofibroblasts triggers the tumors (Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015, Saba 2017)( Hendrick MJ., 1999). Fig. 02. (Cecco, B.S., et al., 2019) The sites where FISS occurs (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2019.08.009) Reports show significant correlation between the rabies and/ or FeLV vaccinations in the development of FISS (Hendrick, Goldschmidt et al. 1992, Kass, Barnes et al. 1993, Hendrick, Shofer et al. 1994). Despite many causes are associated with what triggers the tumor, higher risks are seemed to be coming from vaccines, specifically adjuvanted (Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). Discovered were traces of adjuvants in the inflammatory reaction and later in histological sections (Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). Particles of grey- brown material in the necrotic centre and within the cytoplasm of macrophages were reported consistent with an inflammatory reaction (Hendrick and Dunagan 1991, Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Martano, Morello et al. 2011). The infiltrates reported includes macrophages often having cytoplasmic material, giant cells, lymphocytes and mixed neutrophils and eosinophils. Further, identified in the tumors were cytokines, growth factors and mutations in tumor suppressor genes (Ladlow 2013, Carneiro, de Queiroz et al. 2018). While fibrosarcoma is commonly diagnosed, some histological types were also reported to include: malignant fibrous histiocytoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, myxosarcoma, liposarcoma, nerve sheath tumor, poorly differentiated sarcomas, and extraskeletal osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma (Esplin, McGill et al. 1993, Hendrick and Brooks 1994, Hershey, Sorenmo et al. 2000, Dillon, Mauldin et al. 2005, Saba 2017). According to Saba. C, 2017, any sarcoma that develops within the vicinity of vaccination or injection site should be considered an FISS and thus, should be treated aggressively. While tumors are invasive and variable in size, Martano M.E., et al, 2011 reported that large sized may be due to rapid growth. On the other hand, there could also be delayed in appearance due to its interscapular or deep location (Bowlt 2015). The mass can also be mobile or intensely adherent to the underlying tissue which is usually not painful, but solid and may be cystic (Bowlt 2015). These tumors that develop commonly in sites of injection can reach several centimetres in diameter within a few weeks (Martano, Morello et al. 2011). Since not all cats develop this tumor after vaccination, suggestions are due to genetic predisposition, with higher case of FISS occurrence in siblings of affected cats. Further, some cats may develop more than one FiSS (Hartmann, Day et al. 2015). III. Staging / Diagnosis To properly react with the tumor, proper staging shall be performed. Once a histological diagnosis has been confirmed (Bowlt 2015), it requires complete blood count, a serum biochemical panel, urinalysis, 3-view thoracic radiography, lymph node examination by palpation, and ultrasonography of the abdominal cavity and cytology when applicable (Séguin 2002, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Abdominal ultrasound may be required, depending on the location of the tumor. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lesion and the thorax is required to see the actual size and evaluate the extent of the tumor (Cronin, Page et al. 1998, McEntee and Page 2001, Martano, Morello et al. 2011, Rousset, Holmes et al. 2013, Travetti, di Giancamillo et al. 2013, Saba 2017, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Thoracic radiography is then performed to exclude metastatic deseases, which has 10- 24% chances (Saba 2017, Zabielska-Koczywąs, Wojtalewicz et al. 2017). Whereas, there is as high as 45% for the recurrence rate even after performing surgical excision (Cronin, Page et al. 1998) IV. Treatment Considering the possibility of misdiagnosing the tumor as a granuloma from small tissue samples, and the fact that these can be heterogeneous, incisional biopsy can be done at sites that can be easily excised (Martano, Morello et al. 2011). The indications for a biopsy are based in 3-2-1 rule (Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force, 2005; Vaccine-Associated Feline Sarcoma Task Force guidelines, 1999; (Morrison and Starr 2001). This incisional biopsy is strongly recommended for masses that has persisted for >3 months, is >2 cm, and/or is growing over the course of 1 month post injection in the site (Saba 2017). Radical surgery or wide excision may be recommended. Surgery will be

Canine Anaplasmosis

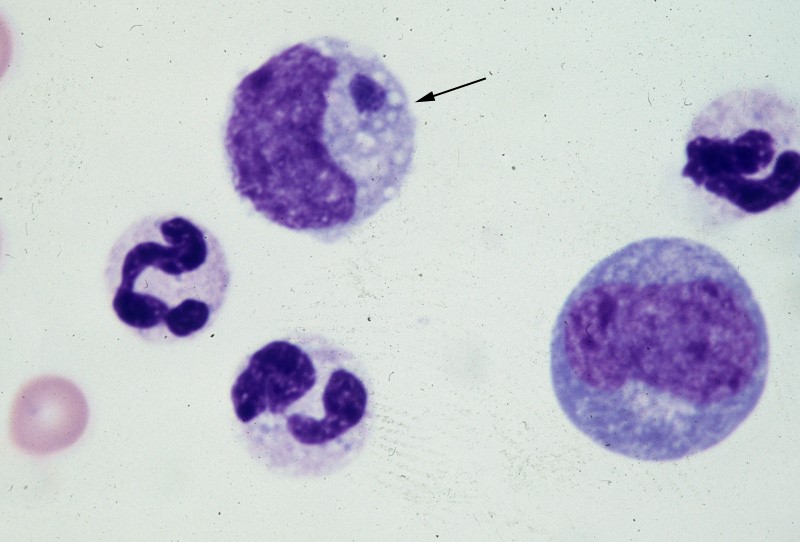

Canine Anaplasmosis Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Anaplasma platys (formerly Ehrlichia platys) is a Gram negative, non-mobile, pleomorphic bacterium, belonging to the Anaplasmataceae family, which has been speculated, but not conclusively demonstrated, to be transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, known as the “brown dog tick” (Simpson et al. 1991). Anaplasma platys is an obligate intracellular microorganism, which appears to parasitise dog platelets exclusively, causing a Canine Vector-Borne Disease (CVBD) named Infectious Canine Cyclic Thrombocytopenia (ICCT) (Cardoso et al. 2010) due to the thrombocytopenia that relapses every 7-14 days (Harrus et al. 1997). Since its first identification in Florida (Harvey et al. 1978), A. platys infection has been reported in several countries around the world, including the United States, China, Thailand, India, Japan, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Israel and Australia (Abarca et al., 2007, Abd Rani et al. 2011, Brown et al. 2001, Cardozo et al. 2009, French et al. 1983, Hua et al. 2000, Inokuma et al. 2001, Suksawat et al. 2001). With regard to Europe, the presence of A. platys has been reported in France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal, and Croatia and in 2 dogs imported in Germany (Beaufils et al. 2002, De La Fuente et al. 2006, Dyachenko et al. 2012, Ferreira et al. 2007, Kontos et al. 1991). Despite the increasing interest in Vector Borne Pathogens (VBPs) affecting dogs in Italy (Dantas‑Torres et al. 2012), the infection by A. platys is poorly documented and considered to be sporadic throughout the country. Nonetheless, A. platys has been serologically and molecularly detected in dogs from Southern regions (Sicily, Apulia and Abruzzo), mostly in co-infection with other VBPs (16, 17, 35, 37,39). Moreover, the DNA of this pathogen has also been found in R. sanguineus ticks by PCR (Sparagano et al. 2003). Diagnosis Blood tests and a urinalysis are the main diagnostic tools for anaplasmosis. The blood tests usually include a complete blood count, blood smear evaluation, biochemistry panel, serology to look for antibodies, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. If the dog is lame, radiographs and analysis of joint fluid are usually included. Among the current available diagnostic methods for detection of A. platys infection, the most used include morulae identification in the blood smears, antibody detection and DNA amplification by PCR (Otranto et al. 2010). Demonstration of the intra-platelet inclusion bodies of A. platys on blood or buffy-coat smears commonly represents the first diagnostic approach in A. platys infection, especially during the acute phase of disease. On the basis of the study described in this article, an accurate, light microscopy analysis of the stained blood smears appears to be a reliable method to point the diagnosis in the direction of A. platys infection, as it allowed platelet cytoplasmic inclusions resembling A. platys morulae to be detected and acute infection to be suspected in all 3 clinical cases. However, a definitive detection of the organisms in blood films may be difficult and cannot be considered a reliable diagnostic method in the chronic phase of the infection due to the cyclic course of bacteraemia, the rarely found parasitaemia and the fairly frequent presence of a very low number of infected platelets (Harrus et al. 1997, Otranto et al. 2010). Furthermore, it should be considered that inclusion bodies within platelets may be present and related to platelet activation during inflammation and E. canis infection and, thus, misdiagnosed as A. platys morulae (Ferreira et al. 2007). Serological methods, such as IFAT, were not taken into account in the diagnostic approach of A. platys infection because they are uncommonly applied, due to the difficulty in obtaining A. platys-infected platelets to use as antigen (A. platys has not yet been cultured) (Lai et al. 2011, Martin et al. 2005) and the possible false-positive results linked to the serologic cross-reactivity between organisms belonging to the same sero-group (e.g. A. phagocytophilum). Recently, a simple qualitative in-clinic Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), the Snap®4Dx Plus (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, USA) was developed in order to identify antibodies against A. platys, as well as to detect Dirofilaria immitis antigen and antibodies for further VBPs e.g. A. phagocytophilum, E. canis, E. erwiingi, B. burgdorferi. Similarly, some rapid tests developed by bioguard or biogen also detect the antibodies against A. platys and other VBP. Thess rapid tests gained favour among small-animal practitioners due both to its ease of use and its accuracy; however, is not able to distinguish between A. phagocytophilum and A. platys. Moreover, the presence of anti-A. platys antibodies does not mean clinical infection, but rather exposure to the infectious agent (Martin et al. 2005). Recently, more specific and sensitive strategies focusing on molecular methods based on PCR approaches were employed (Eddlestone et al. 2007, Ferreira et al. 2007, Inokuma et al. 2002, Lai et al. 2011, Martin et al. 2005) to enable the diagnosis of active cases of A. platys infection, which would otherwise have gone undetected due to low‑sensitivity of microscopy and the low-specificity of the serological diagnosis. It has been demonstrated that PCR is positive even in the case of low-level parasitaemia (Otranto et al. 2010). Several PCR assays were optimized to allow for accurate identification of A. platys infection in dogs using different targets (16S rRNA, p44, groESL, gltA). Therefore, the PCR test, confirmed by a sequence analysis of amplicons, is the most reliable diagnostic test for this pathogen to date (Aguirre et al. 2006, De La Fuente et al. 2006, Gaunt et al. 2010). Treatment Treatment includes antibiotics, pain relievers, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Doxycycline is the most used antibiotic. Most dogs respond within one to two days after they first take doxycycline. Other antibiotic options are tetracycline or minocycline. Analgesia and anti-inflammatory drugs may be needed for joint pain. Let your veterinarian choose the anti-inflammatory, rather than choosing and dosing it yourself, because dogs metabolize these medicines differently than humans do. Your veterinarian will have the most appropriate medication. Disease Prevention Appropriate tick control is critical to preventing this disease. Preventing ticks from

Breed-related disease: Bull Terrier

John K. Rosembert Descended from the extinct old English bulldog and Manchester terrier, the bull terrier was originally bred to help control vermin and to fight in the blood sports of bull and bear baiting. Today’s iteration looks as different as he behaves. With the most recognizable feature is its head, described as ‘egg-shaped head’, when viewed from the front; the top of the skull is almost flat. The profile curves gently downwards from the top of the skull to the tip of the nose, which is black and bent downwards at the tip, with well-developed nostrils. The lower jaw is deep and strong. The unique triangular eyes are small, dark, and deep-set, it is a very recognizable breed. The Bull Terrier is a people dog, plain and simple. He’s happiest when he’s with his family so he’s a terrible choice for an outdoor dog. However, that isn’t to say he wants to lie adoringly at your feet. He’d much rather you got up and came outside with him, and went on a short stroll of, say, 10 miles. Those excursions might be a lot more fun if he weren’t an infamous leash-tugger with a tendency to go chasing after every dog, cat and squirrel he sees. Be prepared to train him to listen to you – something he’ll have a hard time seeing the value of much of the time. Training isn’t optional with this breed, unless the idea of a dog weighing between 45 and 80 pounds dragging you all over the neighborhood and ignoring every word you say in your own house appeals to you. Train your Bull Terrier from puppyhood on, with an emphasis on consistency, and you’ll have a well-behaved, well-socialized canine family member. Bull terriers can be protective, especially if they think their family is in danger, so be sure to socialize them around strangers and don’t encourage aggressive or guarding behavior. They can also be protective of their own space, toys, and food. This behavior must be caught early and corrected consistently, as it can lead to serious behavior problems. Common Bull Terrier Diseases & Conditions Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment Patella luxation. Affects Bull Terriers quite often and is simply a disorder that causes the dislocation of the kneecap. Heart Defects and Heart Disease. Heart defects in Bull Terriers are also quite common and can include cardiac valves that leak or valves that are too narrow to transport blood in the required amount. These defects can result in heart murmurs or irregular heartbeats. Symptoms to look out for include: coughing, lethargic behavior, excessive weight loss or weight gain and distressed breathing. See a vet for assistance if you are observing any of these signs. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD). PKD affects both the Bull Terrier and the Miniature Bull Terrier. It’s a condition that is inherited and symptoms can start to show at a young age. Polycystic Kidney Disease causes cysts of fluid to form in the kidneys, obstructing them from functioning properly. Look for symptoms like: poor appetite, vomiting, drinking excessively, dry or pale gums and lethargic behavior. Deafness, like any breed, occurs in Bull Terriers and can be detected from as early as four weeks of age. If you believe your Bull Terrier is suffering from a loss of hearing, your vet can perform some tests to determine the situation. https://bowwowinsurance.com.au/dogs/dog-breeds/bull-terrier/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/bull-terrier#grooming Photo credit https://animalscontent.blogspot.com/2019/11/bull-terrier.html

Breed-related disease: Bombay cat

The Bombay is one of several breeds created to look like a miniature version of a wild cat. In Bombay’s case, it is the Mini-Me of the Black Panther and does quite a good impersonation indeed. To achieve the breed, breeders took two different paths. In Britain, they crossed Burmese with black domestic cats. In the United States, where the Bombay’s development in the 1950s is generally credited to Nikki Horner of Louisville, Kentucky, the breed was created by crossing sable Burmese with black American Shorthairs. The Bombay is recognized by the Cat Fanciers Association, The International Cat Association, and other cat registries. The Bombay is a medium-sized cat, she feels considerably heavier than she appears. This breed is stocky and somewhat compact but is very muscular with heavy boning. The Bombay is round all over. The head is round, the tips of the ears are round, the eyes, chin, and even the feet are round. The coat of the Bombay is short and glossy. When the coat is in proper condition, its deep black luster looks like patent leather. It has a characteristic walk. their body appears almost to sway when she walks. Again, this walk is reminiscent of the Indian black leopard. The Bombay is extremely friendly. This cat breed needs one-on-one time with his cat parents. It is a cat breed that does not do well alone all day. The Bombay enjoys snuggling up on your lap and can do so for hours. It is not a very independent cat breed. That said, it may develop a Velcro-like attachment to his pet parent. Younger Bombay kittens are active and playful. Senior Bombay cats tend to enjoy watching and are much less active. This cat breed is perfect for either apartment or farm living. They are quiet cats that enjoy interactive play. The Bombay enjoys playing with anything that is lying around and is playful when there is someone to play with. This wonderful cat breed is super soft to cuddle with and is easy to live with. The Bombay needs plenty of love, fun cat toys, and mental stimulation. This cat breed is not very vocal. The Bombay is generally healthy, but some of the problems that affect the breed are as below: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) : is the most common form of heart disease in cats. It causes thickening (hypertrophy) of the heart muscle. An echocardiogram can confirm whether a cat has HCM. Avoid breeders who claim to have HCM-free lines. No one can guarantee that their cats will never develop HCM. Excessive tearing of the eyes : Bombay cats can also suffer from the excessive tearing of the eyes, which can be treated with drops. As with all cats, it’s important to keep an eye on your pet as they get older, which is when they might start to show signs of developing health conditions. Sources: https://www.thesprucepets.com/bombay-breed-profile-551859#characteristics-of-the-bombay-cat http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/bombay#health

Breed-related disease: Doberman

Doberman Pinschers originated in Germany during the late 19th century, mostly bred as guard dogs. Their exact ancestry is unknown, but they’re believed to be a mixture of many dog breeds, including the Rottweiler, Black and Tan Terrier, and German Pinscher. Dobermans are compactly-built dogs—muscular, fast, and powerful—standing between 24 to 28 inches at the shoulder. The body is sleek but substantial and is covered with a glistening coat of black, blue, red, or fawn, with rust markings. These elegant qualities, combined with a noble, wedge-shaped head and an easy, athletic way of moving have earned Dobermans a reputation as royalty in the canine kingdom. A well-conditioned Doberman on patrol will deter all but the most foolish intruder. Doberman’s qualities of intelligence, trainability, and courage have made him capable of performing many different roles, from police or military dog to family protector and friend. The ideal Doberman is energetic, watchful, determined, alert, and obedient, never shy or vicious. That temperament and relationship with people only occur when the Doberman lives closely with his family so that he can build that bond of loyalty for which he is famous. A Doberman who is left out in the backyard alone will never become a loving protector but instead a fearful dog who is aggressive toward everyone, including his own family. The perfect Doberman doesn’t come ready-made from the breeder. Any dog, no matter how nice, can develop obnoxious levels of barking, digging, counter-surfing, and other undesirable behaviors if he is bored, untrained, or unsupervised. And any dog can be a trial to live with during adolescence. Start training your puppy the day you bring him home. Even at eight weeks old, he is capable of soaking up everything you can teach him. Don’t wait until he is 6 months old to begin training or you will have a more headstrong dog to deal with. Doberman are generally healthy, however, like other breeds, they have some problems that occur more frequently than in general dog population, below are some of the most common diseases in Doberman CARDIOMYOPATHY: is a disease of the heart muscle that results in weakened contractions and poor pumping ability. As the disease progresses the heart chambers become enlarged, one or more valves may leak, and signs of congestive heart failure develop. This disease is suspected to be an inherited disease in Dobermans. Research is in progress in several institutions. An echocardiogram of the heart will confirm the disease but WILL not guarantee that the disease will not develop in the future. HIP DYSPLASIA: is inherited. It may vary from slightly poor conformation to malformation of the hip joint allowing complete luxation of the femoral head. Cervical vertebral instability (CVI): commonly called Wobbler’s syndrome. It’s caused by a malformation of the vertebrae within the neck that results in pressure on the spinal cord and leads to weakness and lack of coordination in the hindquarters and sometimes to complete paralysis. Symptoms can be managed to a certain extent in dogs that are not severely affected, and some dogs experience some relief from surgery, but the outcome is far from certain. While CVI is thought to be genetic, there is no screening test for the condition. Dobermans are also prone to the bleeding disorder known as von Willebrand disease, as well as hypoadrenocorticism, or Addison’s disease. Sources: http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/doberman-pinscher#overview https://dpca.org/breed/health/ Photo credit: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/149674387587185244/ https://dogtime.com/dog-breeds/doberman-pinscher#/slide/1

Chlamydophila felis: A Unique Bacteria Causing Diseases to Felines

Chlamydophila felis: A Unique Bacteria Causing Diseases to Felines Maigan Espinili Maruquin Structure and Replication The chlamydiae is unique obligate intracellular bacteria. The Chlamydophila felis is a Gram- negative and rod- shaped coccoid bacterium however the cell wall lacks peptidoglycan (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). It has two morphologically distinct structures. The (1) EB or elementary body is metabolically inert infectious, round and small (~0.3 μm), and is responsible for its survival in extracellular environment with its ‘spore-like’ form with a rigid cell wall. It holds the central and dense nucleoid. Whereas, the other form (2) RB or the replicative but noninfectious reticulate body which is larger (~1 μm) than the EB. It has cross-linked membrane proteins which makes it structurally flexible and osmotically fragile. It contains RNA and diffuse and fibrillary DNA, allowing intracellular replication, nutrient uptake and transportation, protein synthesis and other metabolic activities (Bedson and Bland 1932, Moulder 1991, Nunes and Gomes 2014). The chlamydiae is unique for its biphasic developmental cycle of 30–72 hours (Nunes and Gomes 2014). This bacteria, during its intracellular life, stays in a parasitophorous vacuole, or inclusion to acquire the nutrition it needs. (Hybiske and Stephens 2007). First, the EB attaches and enters the host cell which leads to formation of vacuole. Inside the inclusions, the EB differentiates from the RB. The RB then replicates via binary fission (Borges, V. et. al., 2013) (Nunes and Gomes 2014). The inclusions then expand while RB undergoes transition or conversion back to EB. Finally, the bacteria is released through host cell lysis or via extrusion (Hybiske and Stephens 2007, Nunes and Gomes 2014). Fig. 01. The unique biphasic developmental cycle of Chlamydiae (Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Chlamydia-undergo-a-unique-biphasic developmental-cycle-The-infectious-form-of_fig3_268229035 ) Chlamydophila felis Epidemiology The Chlamydiaceae is reported to have cause animal infection often indirectly and associated with other pathogens (Schautteet and Vanrompay 2011, Nunes and Gomes 2014). The Chlamydophila felis grows in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells and produces inclusion bodies (Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). The C. felis requires close contact between cats to transmit while ocular secretions are considered the most important body fluid for the infection. The disease caused by the C. felis is common in multi- cat environments (Wills JM et al., 1987)(Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) while it is also frequently associated with conjunctivitis (WILLS, HOWARD et al. 1988, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Despite the low zoonotic potential, possible exposure to the C. felis is through handling of infected cats, by contact with their aerosol and also via fomites (Baker 1942, Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). Reports in culture and PCR (Sykes, Anderson et al. 1999, Sykes 2005) showed that C. felis most likely to infect cats less than a year of age and less likely for cats age 5 years above. There is no strong breed or sex preference and prevalence of asymptomatic cases are low (Sykes 2005). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis The C. felis is known to cause conjunctivitis associated with severe swelling of the lid, mild rhinitis, ocular and nasal discharges, fever, and lameness (Masubuchi, K, et al. 2002)(TerWee, Sabara et al. 1998, Rodolakis and Yousef Mohamad 2010). In kittens, chlamydiosis most commonly cause pneumonia and conjunctivitis (TerWee, Sabara et al. 1998, Yan, Fukushi et al. 2000)( Sykes, J. E., 2001)(Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011) and can cause disease to adults, too (Sykes 2005, Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). While C. felis affects conjunctival epithelial cells, natural transmission occurs by close contact with other infected felines, aerosols, and fomites with approximately 3 to 5 days of incubation period (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Generally, conjunctival shedding ceases at around 60 days after infection, however some cats may carry persistent infection (O’Dair HA , et al, 1994; Wills JM., 1986;) (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Due to the reported chlamydial conjunctivitis in the rectal and vaginal excretion from cats, intestinal and reproductive tracts were considered sites for the persistent infections (Wills JM., 1986)(Sykes 2005). On the other hand, findings of the C. felis were also in lung, spleen, liver, kidney and peritoneum of cats (Dickie CW, Sniff ES, 1980; Hoover EA, 1980) (Baker 1944, Masubuchi, Nosaka et al. 2002, Sykes 2005). Other microorganisms may coinfect C. felis. Felines infected by C. felis show clinical signs including: sneezing, transient fever, inappetence, weight lost, nasal discharge, vaginal discharge, lameness and lethargy (Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). Unilateral ocular disease may appear during the first day or two which progresses to bilateral. Discharge in the ocular is watery which becomes mucoid or mucopurulent while chemosis can be observed in the conjunctiva. However, although the cats show symptoms after infection, they mostly still continue to eat (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Fig. 2. A young cat from a multi- cat household showed chlamydial conjunctivitis (Heinrich, C., 2017). (Source: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Bacterial-conjunctivitis-Chlamydophila-felis-Heinrich/12a1d5eee2fbc8121665d94441ff698531c32868 ) Diagnosis Although the use of indirect immunofluorescence can be used to detect the serum antibody titer, this method should be used after a diagnosis of considerable rise in antibody titer (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). On the other hand, cell culture is considered to be the golden standard in diagnosing chlamydial infections (Pointon AM, et al., 1991) (Wills JM, et. al., 1988) (Sykes 2005). The cell culture technique uses fluorescent antibodies in detecting inclusions. However, cell culture isolation is a demanding, time-consuming and expensive technique while sensitivity of the culture may vary depending on the equipment being used and the technical expertise (Sykes 2005). Further, Giemsa staining can be used for inclusions but this causes confusion with other basophilic inclusions (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) Also, conjunctival smears can be Giemsa stained to look for inclusions, but chlamydial bodies are easily confused with other basophilic inclusions (Streeten BW, Streeten EA, 1985) (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) and inclusions are often seen only on early infection, and at times, they are not visible (Wills JM, 1986)(Sykes 2005). For a quicker, less expensive and more sensitive diagnosis than cell culture and

Vector-borne disease: Ehrlichia spp. infection

Vector-borne disease: Ehrlichia spp. infection Canine Ehrlichiosis Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Ehrlichiosis is a disease of dogs, humans, livestock, and wildlife that is widely distributed around the world and is transmitted by tick vectors. The pathogen of the disease, Ehrlichia, was renamed and classified in 2001 according to the bacterial 16S RNA and groESL gene nucleic acid sequences, and is classified as Rickettsiales, Anaplasmataceae, Ehrlichia genus of bacteria (Allison and Little, 2013).) With global warming, the expansion of tick habitats and the prevalence of cross-border tourism, the chances of the disease spreading to non-endemic areas have increased. How is a dog infected with Ehrlichia? Ehrlichiosis is a disease that develops in dogs after being bitten by an infected tick. In the United States, E. canis is considered endemic in the southeastern and southwestern states, though the brown dog tick is found throughout the United States and Canada. (Photo credit: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/ehrlichiosis-in-dogs) Pathogens and transmission. Ehrlichia spp. are gram-negative, small, obligatory intracellular bacteria. There are currently three types of Ehrlichia spp.: not limited to dogs: Elyse infection, dogs as hosts: E. canis, E. chaffeensis, and E. ewingii. E. canis can infect dogs causing monocytic ehrlichsis (canine monocytic ehrlichsis, CME). Cells most commonly infected by E. canis are monocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 1). CME occurs mainly in tropical and subtropical regions, but there are also cases of infection in other regions. E. chaffeensis infects single-core balls of dogs and humans, mainly in North America, South America, Asia and Africa. E. ewingii is a zoonotic infectious disease that infects particulate white blood cells and is found mainly in North America, South America and Cameroon, Africa. E. ewingii causes human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Bulleretal., 1999). E. chaffeensis infects humans known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis. E. canis also causes human infections (Maeda et al., 1987). Ehrlichia spp. life history is that of vector ticks and mammalian hosts. After sucking the blood of infected animals, the larvae transmit the disease to the new host via saliva when they bite and suck the blood of other animals. E. canis, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii have been shown to mediate life cycle transmission in an intermediary hosts that are usually arthropods. This have shown to stabilize its life cycle transmission, which is also known as Transstadial transmission in arthropods, and blood transfusions or bone marrow may also cause the spread of the disease. The main vector arthropods in E. canis are Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Dermacenter variabilis even though the main host are canines including domestic dogs. Other canine family it can infect are wolves, coyotes, and foxes. The other species, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii consist of hosts from the arthropod family such as Amblyomma americanum, a main vector and other arthropods such as Haemaphysalis, Dermacentor, and Ixodes. E. chaffeensis usually infects white-tailed deer, and E. ewingii to hosts that are likely deer and dogs. Figure 1. Ehrlichia canis in the monocyte (arrow) (Wright’s stain, 1000x) (Source: http://www.eclinpath.com/ngg_tag/infectious-agent/nggallery/page/9) Clinical symptoms. The clinical symptoms and severity of Ehrlichiosis depend on the type of Elysian infection and the host’s immune response. The course of E. canis infection in dogs can be divided into acute, subclinical and chronic, but in naturally infected dogs it is not easy to distinguish between these three stages. If there is a co-infection with other pathogens, it will also aggravate the severity of the disease. The acute period lasts about three to five weeks and can cause fever, poor spirits, loss of appetite, swollen lymph nodes and swollen spleen. Increased eye secretions, pale mucosa, bleeding disorders (bleeding spots, or runny nosebleeds), or neurological symptoms caused by meningitis. Vomiting, diarrhea, lameness, reluctance to walk, stiff pace, and leg or scrotum edema. The most easily observed hematological abnormalities are white blood cell reduction, platelet reduction, and anemia. When clinical symptoms disappear, they are often accompanied by subclinical periods that last for several years (Waner et al., 1997). Although some cases can be fatal, others heal on their own. When a dog is unable to clear the pathogen of infection, the course of the disease develops into a subclinical persistent infection to become a primary dog. Some infected dogs enter a chronic period. During the chronic period, symptoms and hematological abnormalities, including platelet reduction, anemia and total blood cell reduction, all relapse and become more severe than it was during acute periods. When the severity maximizes in a few cases, the dogs will not respond to antibiotic treatment and ceased to heal, and eventually they die from heavy bleeding, severe weakness, or secondary pathogenic infections. Many times, when an infected dog that has contracted E. chaffeensis, the diagnoses points out to other pathogens since there are little information as to E.chaffeensis and dog infections also, the clinical symptoms are similar to that of infection with E. canis. Symptoms include easy bleeding (bleeding spots, blood urine or nosebleeds), vomiting, and swollen lymph nodes. The most common symptom of infection with E. ewingii is fever. Other symptoms include lameness, multiple arthritis, terminal edema, swollen lymph nodes, reduced platelets and anemia, some of which can cause neurological symptoms in dogs. Diagnosis. Ehrlichiosis can be diagnosed by microscopy, serology, or PCR. Diagnosis is complicated when other arthropod-mediated pathogens are used. Blood smears have been observed to infect blood cells to help diagnose the disease. However, this method is time-consuming and can only be observed in a small number of cases during acute infection, so it is not a reliable diagnostic method. Serological examinations are often used to assess Ehrlichiosis. Detection of IgG antibody deposits indicated that dogs had been exposed to pathogens, and two serological examinations two weeks apart during the acute period showed an increase in antibody force prices. Caution should be exercised when a single test result is judged, as healthy dogs may also be antibody positive. Antibodies cannot be detected in the early stages of infection. Additionally, antibodies produced during and after an infection with E.canis, E. chaffeensis, or