Breed-related disease: Cymric cat

Is it really a cat if it doesn’t have a tail? It is if it’s a Cymric (pronounced kim-rick). There are lots of cats with short tails or no tails, but the Cymric (and his sister breed the shorthaired Manx) is the only one specifically bred to be tail-free. Sometimes jokingly said to be the offspring of a cat and a rabbit (however cute the idea, a “cabbit” is biologically impossible), these particular tailless cats are the result of a natural genetic mutation that was then intensified by their remote location on the Isle of Man, off the coast of Britain. The cats are thought to date to 1750 or later, but whether a tailless cat was born there or arrived on a ship and then spread its genes throughout the island cat population is unknown. The island became known for tailless cats, and that is how the breed got its name of Manx. The Manx has long been recognized by the Cat Fanciers Association, The International Cat Association, and other cat registries. A longhaired version was accepted by CFA as a division of the Manx in 1994. In some associations, the longhaired Manx is called a Cymric and is considered a separate breed. The overall appearance should be that of a medium-sized, compact, muscular cat. The Cymric has a round head with a firm muzzle and prominent cheeks, short front legs, height of hindquarters, great depth of flank, and a short back, which forms a smooth continuous arch from the shoulders to the round rump. The Manx and Cymric are essentially the same in all respects, the Cymric having a longer coat. The Cymric has a medium/semi-long coat with a silky texture, which varies with coat color. Britches, tufts of hair between the toes and full furnishings in the ears distinguish the Cymric. The personality of the Cymric has won a strong following. Cymrics are intelligent, fun-loving cats, and they get along well with other pets, including dogs. Cymrics are particularly noted for their loyalty to their humans and enjoy spending quality time with them. As cats go, they can be easily taught tricks. Despite their playful temperament, they are gentle and nonaggressive. Here below, we listed some of the most common diseases to look for in your Cymric: Congenital Vertebral Malformations Sacrocaudal dysgenesis is a form of spinal deformity commonly seen in Cymric kittens. The sacrum is the part of the spine that passes through the pelvis, caudal means “towards the tail”, and dysgenesis means improper formation during fetal development. Sacrocaudal dysgenesis, then, means that the tail end of the spine forms improperly during fetal development—a common problem when a cat’s tail is genetically programmed to be missing. Affected kittens whose spine and spinal nerves aren’t functioning correctly may have fecal or urinary incontinence, or may walk with a hopping, abnormal gait. Constipation and megacolon are also more common in affected cats, and the effects of the condition typically worsen with age. Megacolon Megacolon is a serious and chronic form of constipation caused by a defect in the nerve supply to the intestines. Cats with megacolon have an insufficient number of nerves linked to the muscles of the colon and are unable to pass stool properly. As the cat gets older, the condition worsens, causing an increase in discomfort and blockage. Each time the cat is constipated, the intestines are stretched, bruised, and further damaged. This damage leads to larger and harder stools and, eventually, complete blockage. Megacolon is a life-threatening condition, but early and aggressive treatment can delay or prevent the necessity of major surgery to remove the colon. FLUTD When your cat urinates outside the litter box, you may be annoyed or furious, especially if your best pair of shoes was the location chosen for the act. But don’t get mad too quickly—in the majority of cases, cats who urinate around the house are sending signals for help. Although true urinary incontinence, the inability to control the bladder muscles, is rare in cats and is usually due to improper nerve function from a spinal defect, most of the time, a cat that is urinating in “naughty” locations is having a problem and is trying to get you to notice. What was once considered to be one urinary syndrome has turned out to be several over years of research, but current terminology gathers these different diseases together under the label of Feline Lower Urinary Tract Diseases, or FLUTD. Sources: https://ahcfargo.com/client-resources/breed-info/cymric-longhaired-manx-2/ https://cattime.com/cat-breeds/cymric-cats#/slide/1 Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cymric_cat https://www.petfinder.com/cat-breeds/cymric/

Breed-related disease: Maltese dog

John K. Rosembert The Maltese is an ancient breed, one of several small “bichon” dogs found around the Mediterranean for thousands of years. His exact place of origin is a mystery, with conjecture including Sicily, Egypt, and southern Europe, but most historians pinpoint Malta for the development of the breed. With its teeny-tiny stature, flowing white coat, and high trainability, this toy breed has beauty and brains. For that, it’s been cherished since its earliest days in ancient Italy and has long been seen as a portable and charming companion. The Maltese puppy truly is the quintessential lap dog, with its fluffy white fur, adorable black-button nose, dark eyes, and sprightly demeanor. “They’re like a little stuffed animal,” Derse says. The Maltese has a compact, athletic body, small floppy ears, and a tufted tail that curves over her back. By the time a Maltese reaches her full 7–9 inch height and 4–6 pound weight, those white tresses become silky smooth, requiring daily brushing along with regular baths to maintain their regal appearance. If you’re looking for a friendly dog with elegance and charm, look no further than the Maltese! With their silky, pure white coats and warm temperaments, it’s no surprise that they’ve made popular companions for people for centuries. People fall head over heels for this breed because of its adorable look, but their loyal personality makes them a fantastic option for anyone that’s looking for a canine friend. You will find no lack of adorableness, loyalty, or intelligence in this famous toy dog breed. Like other toy breeds, Maltese are prone to certain health issues. However, some of these conditions can be prevented if you keep up with routine care and checkups, here below we listed some of the most common illnesses run in their genes… Let’s get started: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Other common health conditions Maltese face affect their intestines. The breed can also develop severe food allergies and sensitivities. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or IBD for short, occurs when your dog’s intestines become overactive with lymphocytes and plasmacytes. These are immune cells that attack harmful organisms in your dog’s gut, but they can cause vomiting and diarrhea when they become overactive. Diet and lifestyle changes will help this condition. Epilepsy Seizures and epilepsy can occur in Maltese as well. These conditions tend to be genetic, so if the dog’s parents or other direct relatives have a history of seizure, then your dog will have a higher chance of experiencing them. Because Maltese dogs have low body weight, they are at risk of experiencing hypoglycemic seizures. Hypoglycemic seizures are caused by low blood sugar levels. Seizures start as an excessive surge of electrical activity in the brain. The surge becomes excessive and overwhelms the neurons, resulting in a temporary malfunction of the brain. Depending on which regions of the brain are affected, a seizure manifests as muscle spasms or other symptoms. Knee Problems Sometimes your Maltese’s kneecap (patella) may slip out of place (called patellar luxation). You might notice that he runs along and suddenly picks up a back leg and skips or hops for a few strides. Then he kicks his leg out sideways to pop the kneecap back in place, and he’s fine again. If the problem is mild and involves only one leg, your friend may not require much treatment beyond arthritis medication. When symptoms are severe , surgery may be needed to realign the kneecap to keep it from popping out of place. Heart murmurs, congestive heart failure This is most often seen with senior Maltese dogs age 10 and up. Because heart murmurs rarely have any outward signs, this is usually discovered during a wellness check when the veterinarian is listening to the dog’s heart. Murmurs do not always lead to congestive heart failure, but they can. These are graded on a scale from 1 to 6. Typically no treatment is required for a grade 1 to 3 murmur. However, this is often a progressive disease. If the murmur worsens to a grade 4, 5, or 6, there can be issues such as troubled breathing, coughing, and exercise intolerance. Sources: https://www.dailypaws.com/dogs-puppies/dog-breeds/maltese https://www.petmaltese.com/maltese-health https://www.holistapet.com/maltese-dog-breed-temperament-personality/ Photo credit: https://thehappypuppysite.com/maltese-lifespan/ https://maltaangelmaltese.com/about-us/

Breed-related disease: Birman Cat

The origin of the Birman cat is not well known, with much of his history tied in with cultural legends, While there is no clear record of the origin of Birman cats, one pair was taken to France around 1919, from which the breed became established in the western world. However, Birman cats were almost wiped out as a breed during World War II and were heavily outcrossed with long-hair breeds (mainly Persians) and also Siamese lines to rebuild the breed. By the early 1950s, pure Birman cat litters were once again being produced. The restored breed was recognized in Britain in 1965. The Birman, also known as the “Sacred Cat of Burma” is semi-longhaired with darker coloring to the points, face, legs, ears, and tail, and a pale toning body color. It is a largish cat with a thickset body and short legs.The Birman cat has blue eyes and four pure white feet. The front gloves covering only the feet, but the rear socks are longer. The head is broad and rounded with medium-size ears. They come in lots of different colors. The Birman is a calm, affectionate cat who loves to be around people and can adapt to any type of home. He likes to play chase with other pets, taking turns being the chaser and the one being pursued. Birmans make friends with kids, dogs , and other cats. In fact, unlike most felines, they don’t especially like being the “only pet,” so you may want to get your Birman a companion – he won’t care if it’s another Birman, a different breed of cat, or even a dog. Birmans aren’t demanding of your attention, but they’ll definitely let you know when they need a head scratch or some petting. Then they’ll go about their business until it’s time for you to adore them again. You should also keep your Birman entertained with interactive toys that require him to do some thinking and moving to pop out treats or kibble. Here we gathered for you the most common Genetic Predispositions about Birmans, let’s get started: Luckily, Birman cats are relatively healthy and aren’t predisposed to any major conditions. But, the common health concerns that plague other cats are things to look out for. These include obesity, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and kidney disease. Obesity Because of the hefty weight of these kitties, they may be more prone to feline obesity, which can cause a myriad of other health concerns. Just like humans, it’s important to do everything you can to help your kitty maintain a healthy weight. By limiting their food intake, exercising them regularly, and keeping up with regular vet visits, you can completely prevent this condition. It is up to the owner of Birmans to make sure they stay at a healthy weight. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) Not specific to Birman cats, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common heart condition in cats. It causes the walls of the heart muscle to thicken and can cause the heart to increase in size. This is a genetically inherited condition, and breeders can check their lines for this condition. HCM is something to always be aware of, even if your kitty has a clean bill of health. HCM ranges in severity and can be treated with supplements, herbs, and other natural remedies. Kidney Disease Some lines of modern Birman cats may descend from Persians, who are also prone to kidney disease. Because of this, Birmans may be more susceptible. Sources: https://canna-pet.com/breed/birman-cat/ https://www.purina.co.uk/cats/cat-breeds/library/birman Photo credit: https://prettylitter.com/blogs/prettylitter-blog/birman-cats-101-pretty-litter https://cats.lovetoknow.com/Birman_Cats

Breed-related disease: French bulldog

The “bouldogge Francais,” as he is known in his adopted home country of France, actually originated in England, in the city of Nottingham. Small bulldogs were popular pets with the local lace workers, keeping them company and ridding their workrooms of rats. After the industrial revolution, lacemaking became mechanized and many of the lace workers lost their jobs. Some of them moved to France, where their skills were in demand, and of course they took their beloved dogs with them. The dogs were equally popular with French shopkeepers and eventually took on the name of their new country. The little dogs became popular in the French countryside where lace makers settled. Over a span of decades, the toy Bulldogs were crossed with other breeds, perhaps terriers and Pugs, and, along the way, developed their now-famous bat ears. They were given the name Bouledogue Français. French bulldogs (Frenchies) are known for their quiet attentiveness. They follow their people around from room to room without making a nuisance of themselves. When they want your attention, they’ll tap you with a paw. This is a highly alert breed that barks judiciously. If a Frenchie barks, you should check it out. What’s not to like? Frenchies can be stubborn about any kind of training. Motivate them with gentle, positive techniques. When you find the right reward, they can learn quickly, although you will find that they like to put their own spin on tricks or commands, especially when they have an audience. All dogs have the potential to develop genetic health problems, just as all people have the potential to inherit a particular disease, The French Bulldog is prone to certain health problems. Here’s a brief rundown on what you should know. Ear Infections French Bulldogs have very narrow ear canals, and for this reason, are very vulnerable to ear infections. They are also susceptible to allergies which can give them these infections. Ear glands swell up to resist infections and produce more wax than normal. This leads to an overproduction of ear tissue, making the canal ever narrower, and inflamed. In severe cases the eardrum can rupture, causing your pooch a lot of pain! Look out for excessive ear scratching and redness inside the ear as warnings of this problem Diarrhea Stomach upsets are very common in Frenchies, so monitoring their diet is a must. Consistent bouts of diarrhea can be caused by parasites, viruses, or E. coli, all of which Frenchies are very sensitive to. Take note of their stools if they are wet, runny, or tarry, smell foul, or if you see blood in the stools. These are all signs of a serious digestion problem. Other tell-tale signs are your dog losing weight, losing their appetite, vomiting or having a fever. Conjunctivitis Again, due to the genetic makeup of French Bulldogs, they are at a high risk of suffering from conjunctivitis. This is because they are a short-nosed (brachycephalic) breed. It’s usually caused by bacterial and viral infections or allergic reactions to substances. Watch out for your Frenchie having pink or red eyes, if they start blinking more than usual, or have mucus, pus or discharge leaking from their eyes. Skin Problems – Skin Fold Dermatitis Due to French Bulldogs folded facial skin around their muzzle and nose, this can lead to dermatitis. It can also occur in other areas of their bodies that are folded, like armpits, necks, and crotches. Signs of this problem include itching, biting and scratching of the area, and redness and sores on the affected skin. Keeping skin folds dry and clean can prevent dermatitis from occurring. Skin Problems – Pyoderma (bacterial skin infection) Another common skin problem is bacterial skin infections. This occurs when your dog has a cut or scratch that becomes infected. Again, look out for itching, red skin, pus, and loss of hair around the cut. It’s another health problem that comes from having skin folds. Breathing Problems – URT Infection As a short-nosed breed, French Bulldogs are very at-risk of upper respiratory tract infections. These will usually happen to every bulldog at least once in their lives and are infectious, so will occur if your dog spends more time with other canines. Symptoms are a lot like human colds: nasal congestion, coughing, and lethargy. Breathing Problems – Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) Sadly, many French Bulldogs are also at a high risk of BOAS due to their squashed faces and short snouts. This can lead to shortness of breath, trouble breathing, sleeping difficulties, and heat intolerance. You’ll notice this problem occurring during exercise and in warmer temperatures. Mobility Issues in French Bulldogs There is a range of conditions that can affect the Frenchie’s mobility. Ranging from congenital conditions, injuries, and degenerative disease. Conditions such as hip dysplasia and luxating patellas can be caused by genetic or caused by old injuries. Other conditions affecting Frenchies include IVDD, spinal disc issues, and degenerative myelopathy (DM). Sources: https://www.handicappedpets.com/blog/common-health-problems-in-frenchies/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/french-bulldog#health Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Bulldog American kennel Club

Bartonella henselae: An Infectious Pathogen among Cats

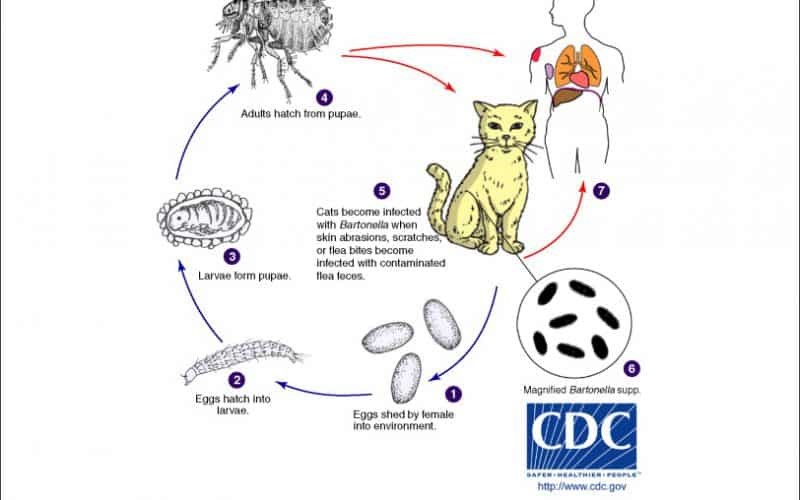

Table of Contents Maigan Espinili Maruquin 1. Introduction Overview of Bartonella henselae as a Significant Feline and Zoonotic Pathogen Bartonella henselae is a small, fastidious, Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium with a global distribution. It exhibits a marked tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes, enabling the establishment of chronic, relapsing bacteremia that may persist for months or even years in infected hosts. Domestic cats are the primary mammalian reservoir and represent the principal source of zoonotic transmission to humans. Kittens and feral cats typically harbor higher bacterial loads, although subclinical infection is widespread across the global feline population. Reported bacteremia prevalence in apparently healthy cats ranges from 8% to 56%, depending on geographic region and flea exposure. The primary competent vector for B. henselae is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), within which the organism replicates in the flea gut and is excreted in flea feces (commonly referred to as flea dirt). These contaminated feces can remain infectious in the environment for at least nine days, facilitating indirect transmission. Importance in Companion Animal Medicine and Public Health From a companion animal medicine perspective, B. henselae is clinically significant because most infected cats function as asymptomatic carriers, silently sustaining zoonotic risk. Nevertheless, increasing evidence links B. henselae infection to sporadic but severe feline disease manifestations, including endocarditis, myocarditis, and ocular inflammatory conditions such as uveitis. In dogs, which are considered accidental hosts, bartonellosis is often more pathogenic and has been strongly associated with culture-negative endocarditis and granulomatous inflammatory disease. In public health, B. henselae is best known as the primary etiological agent of Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) in humans. Transmission most commonly occurs when cat claws or oral cavities become contaminated with infected flea feces, which are then inoculated into human skin through a scratch or bite. Immunocompetent individuals typically develop a self-limiting illness characterized by regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and a papule at the site of inoculation. Immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients, are at risk for severe and potentially fatal complications, such as bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis, encephalitis, and endocarditis, reflecting the organism’s vasoproliferative potential. Scope of the Review and Relevance to Clinical Practice A clear understanding of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and persistence mechanisms of B. henselae is essential for effective clinical management and disease prevention. Diagnosis remains particularly challenging, as the organism is highly fastidious and slow-growing, frequently resulting in false-negative blood culture findings and so-called “culture-negative” infections. Although molecular assays such as PCR and serological testing are widely employed, interpretation is complicated by intermittent bacteremia and the high background seroprevalence among healthy cats. In clinical practice, adoption of a One Health framework is critical. Veterinarians play a central role in mitigating zoonotic risk through owner education, emphasizing strict, year-round flea control, appropriate hygiene, and cautious interaction with cats, especially in households containing immunocompromised individuals. Management is further complicated by the absence of a standardized antimicrobial protocol capable of reliably achieving complete bacteriological clearance in feline hosts. To conceptualize its biological behavior, B. henselae may be likened to a “stealthy hitchhiker.” By residing within erythrocytes and vascular endothelium, the organism evades immune surveillance, periodically re-emerging only to secure transmission via a passing flea. 2. Characteristics and Epidemiology 2.1 Taxonomy and Microbiological Characteristics The genus Bartonella comprises small, thin, fastidious, and pleomorphic Gram-negative bacilli. These organisms are facultative intracellular pathogens with a highly specialized biological niche characterized by a pronounced tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes (red blood cells). Following host entry, Bartonella spp. proliferate within membrane-bound vacuoles, often referred to as invasomes, inside vascular endothelial cells. Periodic release into the bloodstream allows subsequent invasion of erythrocytes, within which the bacteria may persist until cellular senescence or destruction occurs (Cunningham and Koehler 2000; LeBoit 1997). Transmission is predominantly arthropod-borne, involving vectors such as fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), ticks, lice, and sand flies. Although Bartonella species have been isolated from a wide range of mammalian hosts, including rodents, rabbits, canids, and ruminants, domestic and feral cats represent the principal mammalian reservoir for the most epidemiologically and clinically significant zoonotic species, particularly B. henselae (Chomel et al., 1996; Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Guptill, 2012). 2.2 Global Distribution and Seroprevalence Bartonella species exhibit a global distribution, although prevalence varies markedly according to environmental and ecological conditions. In European feline populations, reported antibody prevalence ranges from 8% to 53% (Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Zangwill, 2013), while global serological evidence of exposure in cats spans approximately 5% to 80% (Guptill, 2012). The epidemiology of Bartonella infection is strongly influenced by geography, climate, and flea density. The highest prevalence rates are consistently observed in warm, humid temperate and tropical regions, where environmental conditions favor the survival and propagation of C. felis. In contrast, in colder climates, such as Norway, Bartonella infection in cats is reported to be rare or virtually absent, reflecting the limited persistence of flea vectors under such conditions. 2.3 Species Diversity and Genotypes Although 22 to 38 Bartonella species have been described to date, Bartonella henselae remains the most frequently detected species in both domestic cats and humans. Feline populations may also harbor Bartonella clarridgeiae, identified in approximately 10% of infected cats, while B. koehlerae is detected far less commonly (Guptill, 2012). Considerable regional variation exists among B. henselae genotypes, which are broadly classified into Houston-1 (Type I) and Marseille (Type II) strains. Type II (Marseille) predominates among feline populations in the western United States, western continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Type I (Houston-1) is the dominant genotype in Asia, including Japan and the Philippines, and is most frequently isolated from human clinical cases worldwide, even in regions where Type II strains are more prevalent among cats. Beyond domestic cats, Bartonella infections have been documented in non-domestic felids, including African lions, cheetahs, and various neotropical wild cat species, underscoring the broad ecological adaptability of the genus (Guptill, 2012). To conceptualize its ecological behavior, Bartonella may be viewed as a “weather-dependent squatter.” It establishes itself most successfully in warm, densely populated environments rich in flea vectors,

Feline Pancreatic Lipase (fPL)

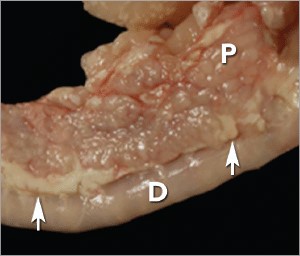

Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Pancreatitis appears to be a common disease in cats,1 yet it remains frustratingly difficult to establish a clinical diagnosis with certainty. Clinicians must rely on a combination of compatible clinical findings, serum feline pancreatic lipase (fPL) measurement, and ultrasonographic changes in the pancreas to make an antemortem diagnosis, yet each of these 3 components has limitations. Acute Versus Chronic Pancreatitis Acute pancreatitis is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation, with variable amounts of pancreatic acinar cell and peripancreatic fat necrosis (Figure 1).1 Evidence is mounting that chronic pancreatitis is more common than the acute form, but sonographic and other clinical findings overlap considerably between the 2 forms of disease.1-3 Diagnostic Challenges Use of histopathology as the gold standard for diagnosis has recently been questioned because of the potential for histologic ambiguity.3,4 A seminal paper exploring the prevalence and distribution of feline pancreatic pathologic abnormalities reported that 45% of cats that were apparently healthy at time of death had histologic evidence of pancreatitis.1 The 41 cats in this group included cats with no history of disease that died of trauma, and cats from clinical studies that did not undergo any treatment (control animals). Conversely, multifocal distribution of inflammatory lesions was common in this study, raising the concern that lesions could be missed on biopsy or even necropsy. Prevalence Such considerations help explain the wide range in the reported prevalence of feline pancreatitis, from 0.6% to 67%.3 The prevalence of clinically relevant pancreatitis undoubtedly lies somewhere in between, with acute and chronic pancreatitis suggested to represent opposite points on a disease continuum.2 FIGURE 1. Duodenum (D) and duodenal limb of the pancreas (P) in a cat with acute pancreatitis and necrosis; well-demarcated areas of necrosis are present at the periphery of the pancreas in the peripancreatic adipose tissue(arrows). Courtesy Dr. Arno Wuenschmann, Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory Risk factors No age, sex, or breed predisposition has been recognized in cats with acute pancreatitis, and no relationship has been established with body condition score.3-5 Cats over a wide age range, from kittens to geriatric cats, are affected; cats older than 7 years predominate. In most cases, an underlying cause or instigating event cannot be determined, leading to classification as idiopathic.3 Abdominal trauma, sometimes from high-rise syndrome, is an uncommon cause that is readily identified from the history.6 The pancreas is sensitive to hypotension and ischemia; every effort must be taken to avoid hypotensive episodes under anesthesia. Comorbidities In cats with acute pancreatitis, the frequency of concurrent diseases is as high as 83% (Table 1).2 Pancreatitis complicates the management of some diabetic cats and may induce, for example, diabetic ketoacidosis.7 Anorexia attributable to pancreatitis can be the precipitating cause of hepatic lipidosis.8 The role of intercurrent inflammation in the biliary tract or intestine (also called triaditis) in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis is still uncertain. Roles of Bacteria In one study, culture-independent methods to identify bacteria in sections of the pancreas from cats with pancreatitis detected bacteria in 35% of cases.9 This report renewed speculation about the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis, and the potential role that the common insertion of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct into the duodenal papilla may play in facilitating reflux of enteric bacteria into the “common channel” in cats. Awareness of triaditis may affect the diagnostic evaluation of individual patients. Table 1. Clinical Data from 95 Cats with Acute Pancreatitis (1976—1998; 59% Mortality Rate) & 89 Cats Diagnosed with Acute Pancreatitis (2004—2011; 16% Mortality Rate) PARAMETER HISTORICAL DATA* CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† SURVIVING CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† Number of Cats 95 89 75 ALP elevation 50% 23% 18% ALT elevation 68% 41% 36% Apparent abdominal pain 25% 30% 32% Cholangitis NA 12% 11% Concurrent disease diagnosed NA 69% 68% Dehydration 92% 37% 42% Diabetic ketoacidosis NA 8% 5% Diabetes mellitus NA 11% 12% Fever 7%‡ 26% 11% GGT elevation NA 21% 18% Hepatic lipidosis NA 20% 19% Hyperbilirubinemia 64% 45% 53% Icterus 64% 6% 6% Vomiting 35%—52% 35% 36% ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; GGT = gamma glutamyl transferase; NA = not available * Summarized from 4 published case series; a total of 56 cats had acute pancreatitis diagnosed at necropsy and 3 by pancreatic biopsy5,8,10,11 † Data obtained from reference12 ‡ 68% of cats were hypothermic DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION Many cats with pancreatitis have vague, nonspecific clinical signs, which make diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical signs related to common comorbidities, such as anorexia, lethargy, and vomiting, may overlap with, or initially mask, the signs associated with pancreatic disease. Early publications on the clinical characteristics of acute pancreatitis required necropsy as an inclusion criterion, presumably skewing the spectrum of severity of the reported cases.5,8,10,11 Cats with chronic pancreatitis were excluded from these reports. Clinical Findings Table 1 lists common clinical findings in cats from necropsy-based reports and a recent series of 89 cats with acute pancreatitis studied by the authors.12 Note the lower prevalence of most clinical findings in the cats diagnosed clinically rather than from necropsy records. In our evaluation of affected cats, 17% exhibited no signs aside from lethargy and 62% were anorexic. Vomiting occurs inconsistently (35%—52% of cats). Abdominal pain is detected in a minority of cases even when the index of suspicion of pancreatitis is high. About ¼ of cats with pancreatitis have a palpable abdominal mass that may be misdiagnosed as a lesion of another intra-abdominal structure. Laboratory Analyses Hematologic abnormalities in cats with acute pancreatitis are nonspecific; findings may include nonregenerative anemia, hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, or leukopenia. Serum biochemical profile results vary (Table 1). In our acute pancreatitis case series, 33% of cats had no abnormalities in their chemistry results at presentation.12 Serum cholesterol concentrations may be high in up to 72% of cases. Some cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with severe clinical syndromes, such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure, that influence some serum parameters, such as albumin, liver enzymes, and coagulation tests. Plasma ionized calcium concentration may be low, and has

Concurrent with T-zone lymphoma and high-grade gastrointestinal cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma in a dog

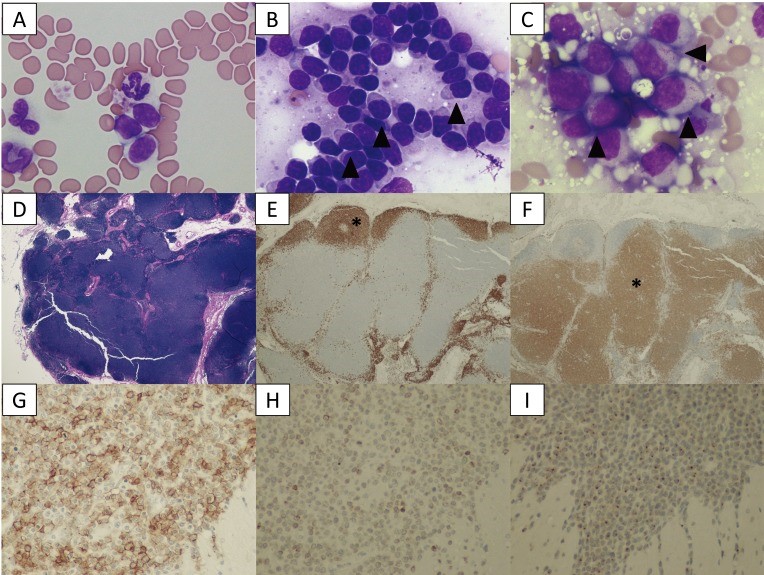

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5402196/ A 9-year-old, spayed female Golden Retriever dog showed lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy, secondary to suspected chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Small-to-intermediate lymphocytes were observed from the cytological examination of the right popliteal lymph node via a fine-needle aspirate. The dog was suspected to have a low-grade lymphoma based on the finding of cytology. Also, ultrasonography reveled thickened lesions in the stomach and small intestine. Histopathology of the popliteal lymph node and small intestine revealed a simultaneous presence of T-zone lymphoma (TZL) and high-grade gastrointestinal (GI) cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements assay suggested that both lymphomas, though both originated in the T-cells, derived from different genes. The dog died 15 days after diagnosis, despite chemotherapy. Fig. 1. A–C: Cytological images on day 1. (A) Peripheral blood smear. Increased numbers of small lymphocytes. (B) Cytology of the popliteal lymph node biopsy. Most lymphocytes are small-to-intermediate, mature lymphocytes. Some lymphocytes show a “hand mirror” type of cytoplasmic extension (arrowhead) (Wright-Giemsa stain, × 400). (C) Slide preparation of tissue from the small intestine. The lymphocytes are intermediate-to-large, immature cells, and some display azurophilic granules in the cytoplasm (LGLs, arrowhead). D–F: Histological images of popliteal lymph node tissue. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. (E) The lymphocytes with fading follicular structures are CD20 positive (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD20, a hematoxylin counterstain. (F) The nodal capsule (CD3 positive) is thinned without the involvement of the perinodal tissue (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD3, hematoxylin counterstain. G–I: Histological images of the intestinal tissue. All lymphocytes are positive for CD20 (G), CD3 (H) and granzyme B (I). Fig. 2. (A) Transverse ultrasound image on day 1 showing a thickened intestinal wall (approximately 9.0 mm, arrowhead). (B) Post-contrast transverse CT image on day 2 also showing a thickened intestinal wall (arrowheads). The intrathoracic and abdominal lymph nodes are enlarged. Fig. 3. PARR analysis. (A) The peripheral blood sample shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. (B) The intestinal tissue sample also shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. The two tumors demonstrate clonal expansions from different primers.

Breed-related disease: Thai Cat

The Thai Cat is an old, but recently recognized breed that is related to the Siamese cat originated in Thailand, where it is actually referred to as the Wichien-Maat, which translates to “moon diamond.” This breed is also commonly referred to as the Traditional, or Old-Style, Siamese. In the 1800s, the first Wichien-Maat cats arrived in Great Britain as a gift to the royal family, where they soon become very popular. The Western breeders renamed the breed to Siamese and started to improve its looks with selective breeding. Thus emerged a cat with finely boned slimmer body, longer head, and more intense sapphire blue eyes. Eventually, the new-styled Siamese was the center of attention and many breeders preferred the new look over the original one. Luckily in the 1950s, some breeders enjoyed the original appearance of these cats and started to breed them to get the original qualities back into the breed. At this point, the two breeds started to diverge. And in 1990, the Thai name was given to cats that had the classic look of Traditional Siamese cats. Finally, in 2009, TICA gave the Thai an Advanced New Breed status. The Thai cat is a shorthaired cat breed that has a flat, short coat that is soft. Their bodies feature medium-sized bones in the legs, head, and tail. And they have a wedge-shaped muzzle, ears that are broad at the base, and a long, flat forehead that distinguishes it from other pointed breeds. These cats also have striking blue eyes that complement their pointed coat beautifully. The Thai is an attention-seeking and demanding breed that craves human companionship. These cats form deep bonds with their owners and will follow them around the house, this breed doesn’t understand the concept of privacy, and the Thai will shadow your every move . While being the center of your cat’s universe has its perks, this amount of devotion can sometimes be too much! Health and Potential Health Problems The Thai is generally a healthy breed that can live very long. Although they aren’t prone to an array of genetic health problems like some other cat breeds, certain issues have been observed in these cats. This doesn’t mean that your cat is going to be affected. However, it is better to learn about any potential problems before bringing a new cat home. Crossed eyes : This condition occurs when small muscles in the eye are stretched out and don’t allow normal movements of the eye. A cat can be born with this condition or develop it later in life. Cats that are born with it don’t experience any problems and have normal lives. However, if the condition appears later in life it is usually because of an underlying issue. Symptoms include uncoordinated eye movement, lack of movement in one eye, seizures, and lethargy. Treatment varies depending on the underlying issue and can include antibiotics or surgery. Kinked Tail : This condition is caused by a recessive gene and it is sometimes seen in Thai Cats. This means that even though both parents have normal tails a kitten can be born with a curled or kinked tail. This condition doesn’t affect the health of a cat. However, affected cats are disqualified from show rings. Gangliosidosis : It’s an inherited disease that causes a cat to lack an enzyme that is required to metabolize certain lipids., excess fats accumulate within the cells disrupting their normal function. Symptoms include in-coordinate walk, enlarged liver, tremors, and visual impairment They are usually observed in kittens between 1 to 5 months of age. Unfortunately, there is no cure for this disease and the affected kittens die when they are 8 months old. However, DNA testing is available and is used to improve breeding programs. Sources: https://www.petguide.com/breeds/cat/thai-cat/ https://thedutifulcat.com/thai-cat/ Photo credit: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Thai_cat

Breed-related disease: Newfoundland

The Newfoundland is a large working dog. They can be either black, brown, grey, or white-and-black. However, in the Dominion of Newfoundland, before it became part of the confederation of Canada, only black and Landseer colored dogs were considered to be proper members of the breed. They were originally bred and used as working dogs for fishermen in Newfoundland. Because of its heavy coat, the Newfie does not fare well in hot weather. It should be kept outdoors only in cold or temperate weather , and in summer, the coat may be trimmed for neatness and comfort, and brushed daily to manage excess shedding and prevent the coat from matting. The dog is at its best when it can move freely between the yard and the house, but still needs plenty of space indoors to stretch properly. Daily exercise is essential, as is typical with all work dogs. Newfoundland is known for his intelligence, loyalty, and sweetness. Even though he is a terrific guard dog, his gentle and docile disposition makes him an excellent choice for as a family dog. He thinks he’s a lap dog, and loves to lean on people and sit on their feet. The Newfie is a natural lifesaver and can be a good assistant for parents who have a swimming pool or enjoy taking the kids to the lake or ocean, although he should never be solely responsible for their safety. Let it be said that the Newfie isn’t perfect, his heroic nature notwithstanding. Any dog, no matter how nice, can develop obnoxious levels of barking, digging, counter-surfing and other undesirable behaviors if he is bored, untrained or unsupervised. And any dog can be a trial to live with during adolescence. In the case of the Newfie, the “teen” years can start at six months and continue until the dog is about two years old. We know you care for your pet that’s why gather some of the various health problems that are common in the breed. Subaortic Stenosis (SAS) This is an inherited disease in Newfoundland’s, although the mode of inheritance appears complicated and is not yet completely understood. A ring of tissue forms below the aortic valve in the heart, restricting the blood flow and increasing the pressure within the heart. The heart tissue overgrows in response to the increased pressure, outgrowing its own blood supply and causing scar tissue to develop that interferes with the electrical impulses in the heart. Puppies can develop a murmur throughout their first year of life, but usually those with significant disease develop murmurs within the first 9 weeks of life. Occasionally, a puppy will have no murmur at a young age, but when checked again at one year, will have developed the disease. Pulmonic Stenosis (PS) In this disease a ring of tissue forms below the pulmonic valve in the heart. It causes murmurs and may affect the dog’s health and life span, depending on the severity and if it appears in conjunction with other defects. Allergies Newfoundland, as well as most other breeds of dogs may allergies to food, fleas, pollen or other environmental allergens. Typically allergies cause skin problems, recurring ear infections or digestive problems. Medications, proper parasite control, and sometimes diet changes can effectively manage many allergies. Panosteitis (Pano) This is a painful inflammatory bone disease of young, rapidly growing dogs. Pano causes lameness in the affected limb and the lameness may “rotate” among all four legs. It is usually a self-limiting condition that most dogs outgrow. The dog may require some limitation of activity, ie no free play, and anti-inflammatory medication if the pup is very painful. Pano commonly occurs between 6 months and 18 months, but is known to occur in older dogs, and tends to run in families. Source: http://www.newfhealthandrescue.org/health.html http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/newfoundland#health Photo credit: https://www.freepik.com/premium-photo/purebred-newfoundland-dog_5575063.htm

Oriental Shorthair White Paper: Breed Characteristics, Health Risks and Care Guidelines

1. Introduction Brief History and Origin of Oriental Shorthairs The Oriental Shorthair is a feline breed classified as a Siamese hybrid, forming part of the larger Oriental Breed Group, which includes the Siamese and Balinese. It is considered a man-made breed, intentionally developed in post–World War II England during the 1950s, when breeders sought to rebuild Siamese lineage programs. To achieve greater phenotypic diversity, the Siamese was crossed with breeds such as the Russian Blue, British Shorthair, Abyssinian, and domestic shorthairs. These early outcrosses produced non-pointed kittens that were subsequently bred back to Siamese lines. The objective was clear, to create a cat identical to the Siamese in type and temperament, but available in a wider range of colors and patterns. While initial color variants were treated as separate breeds, the expanding number of phenotypes prompted consolidation. All non-pointed Siamese-type cats were eventually grouped under one breed name, the Oriental Shorthair. The breed entered the United States during the 1970s and rapidly gained recognition. Popularity, Temperament, and Suitability as Companion Animals The Oriental Shorthair remains popular due to its elegant lines, remarkable behavioral traits, and its extraordinary spectrum of colors, which has earned it the informal name “the rainbow cat.” More than 280 to nearly 300 color and pattern combinations have been documented, with common variations including ebony, white, chestnut, and blue. Its defining traits include: Social and Affectionate: Orientals form intense bonds with their caregivers. They thrive on interaction and are known to experience withdrawal or depressive behaviors when left alone for prolonged periods. Vocal and Expressive: The breed communicates with a distinctive voice, often described as a “little goose honk.” They engage in vocal exchanges and will follow their humans from room to room. Highly Intelligent and Active: These cats display lifelong playfulness and investigative curiosity. When unsupervised, they often engage in high-energy behaviors such as climbing refrigerators, opening cabinets, or observing television with notable attentiveness. Emotionally Sensitive: Their strong attachment makes them vulnerable to environmental instability. Loss of a preferred human or significant routine changes can trigger noticeable emotional distress. As companion animals, Oriental Shorthairs are best suited for households that can provide consistent interaction, environmental enrichment, and emotional stability. 2. Breed Profile and Characteristics 2.1 Physical Characteristics Body Structure, Coat Type, and Color Variations The Oriental Shorthair conforms to the svelte, elongated body plan typical of Siamese-derived breeds. The body is long, refined, and flexible, with no tendency toward roundness. The coat is short, sleek, and fine, lying close to the skin and highlighting the breed’s angular physique. The breed is renowned for its extensive color genetics, with 281–300 documented coat and pattern combinations. (Cat Fanciers’ Association, n.d.; The International Cat Association, n.d.; Brearley, 2016). Commonly encountered colors include ebony, pure white, chestnut, and blue. Recognized pattern groups include solid, bi-color, tabby, smoke, and shaded variants. Distinctive Features Compared with Siamese-Related Breeds Although identical in body type to the Siamese, Balinese, and Oriental Longhair, the Oriental Shorthair differs primarily in: Coloration: The defining feature. Unlike the Siamese, Orientals do not exhibit pointed coloration and instead appear in a vast array of solid or patterned coats. Genotype: Orientals share the same structural genetics as the Siamese. Kittens of both breeds may occur within the same litter, separated only by coat phenotype. Eye Color: The preferred eye color in most Oriental Shorthairs is green, whereas Siamese-pointed colors have blue eyes. These distinctions maintain the breed’s identity while preserving Siamese type characteristics. 2.2 Behavioral Profile The Oriental Shorthair is an affectionate, alert, and highly communicative breed whose intelligence fuels constant exploration and problem-solving behaviors. Owners frequently describe them as emotionally expressive and endlessly curious. Their activity levels remain high throughout life, requiring ample vertical space, interactive toys, and consistent physical engagement. Socially, they form deep bonds with humans and typically integrate well with other pets, but prolonged isolation may trigger anxiety or depressive behaviors. Because of their intense mental and physical needs, environmental enrichment is essential: tall cat trees, puzzle feeders, training sessions, and supervised exploration all help maintain behavioral balance. Their natural attraction to warmth often draws them to sunlit windows, warm laps, or even beneath blankets. 3. Genetic Background and Hereditary Considerations 3.1 Breed Lineage The Oriental Shorthair descends directly from Siamese breeding programs and belongs to the Oriental Breed Group, along with the Siamese and Balinese. This shared lineage results in common genetic predispositions and similar breed-specific vulnerabilities. 3.2 Known Genetic Markers The Oriental Shorthair shares many hereditary conditions with its Siamese lineage, reflecting their close genetic relationship. Key inherited disorders documented in the breed include amyloidosis, a complex systemic disease involving amyloid deposition in organs such as the liver and thyroid, with both Mendelian and polygenic influences suggested. Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is another major concern, leading to gradual vision loss and now readily identifiable through genetic testing. Neurological and sensory conditions are also notable, including Hyperesthesia Syndrome, characterized by episodic agitation and overgrooming, as well as nystagmus, an involuntary ocular movement. Cardiovascular issues such as aortic stenosis and isolated reports of juvenile dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) have been described, alongside respiratory and anatomical tendencies such as asthma-like bronchial disease, dental irregularities linked to head structure, and occasional strabismus. Gastrointestinal vulnerabilities include megaesophagus, pica, and associated risks of obstruction. Additionally, the breed demonstrates increased susceptibility to oncological diseases, particularly lymphoma and mast cell neoplasia, reinforcing the importance of vigilant screening and responsible breeding practices. 3.3 Implications for Breeding and Selection Responsible Breeding Guidelines Breeders are encouraged to adopt structured genetic screening and maintain transparent communication regarding the health status of breeding lines. Given the presence of complex diseases such as amyloidosis, maintaining a broad genetic base is critical to prevent inbreeding depression. Reducing Disease Prevalence Through Genetic Testing PRA Screening: Routine testing helps identify carriers and avoid high-risk pairings. Monitoring High-Frequency Variants: The CEP290 variant affecting late-onset blindness has been identified in approximately 33 percent of surveyed Orientals, necessitating active management. (Wiseman et al., 2007; Hendricks et al., 2021; Embark Veterinary, 2023). Carrier Management: Recessive