The Importance of AGP in FIP Diagnosis: An Overview

Maigan Espinili Maruquin The Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) The coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses with non-segmented genomes of around 30,000 nucleotides in length (Tasker 2018)( Siddell SG, 1995). The feline coronavirus (FCoV) has two pathotypes distinguished by their biological behavior. The highly prevalent feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) is highly contagious with transmission from faeces of shedding cats (Felten and Hartmann 2019). However, most cases are asymptomatic or displays mild gastrointestinal clinical signs, (Addie, Toth et al. 1995, Pedersen, Sato et al. 2004, Pedersen, Allen et al. 2008, Pedersen 2009, Vogel, Van der Lubben et al. 2010, Tasker 2018, Felten and Hartmann 2019). On the other hand, the feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) is a mutation within a small percentage of infected cats and it results to a fatal disease feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), commonly in young cats (Pedersen, Boyle et al. 1981, Pedersen, Boyle et al. 1981, Addie, Toth et al. 1995, Vennema, Poland et al. 1998, Pedersen 2009, Tasker 2018, Felten and Hartmann 2019). However, the exact gene causing mutation is still unknown (Felten and Hartmann 2019). The FIP may appear in two clinically distinct forms: the wet form and dry form, which is effusive and granulomatous forms, respectively (Wolfe and Griesemer 1966, Montali and Strandberg 1972, Pedersen 2009, Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016). The development of FIP is affected by three factors. First is the viral factor wherein studies relative to mutation of the FCoV S gene where presented (Tasker 2018) and the replication in monocytes, and activation of infected monocytes were also considered important in the development of FIP (Kipar and Meli 2014, Tasker 2018). Second factor considered is the host’s immune response, breed and genetic (de Groot-Mijnes, van Dun et al. 2005, Dewerchin, Cornelissen et al. 2005, Golovko, Lyons et al. 2013, Pedersen, Liu et al. 2016, Tasker 2018). Finally, another factor affecting the FIP development is the environment- level of stress and overcrowding (Tasker 2018). https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cat-with-wet-effusive-form-of-FIP-presenting-moderate-abdominal-distention-due-to_fig7_51758582 Fig. 01. Manifestation of moderate abdominal distention due to peritoneal effusion. A clinical sign of wet (effusive) FIP. Common clinical signs for the FIP infected cats include lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, fluctuating pyrexia, and sometimes presents jaundice (Tasker 2018). On the other hand, wet FIP cases can be associated with abdominal, pleural and/ or pericardial effusions, and progresses within few days to weeks with severe limiting survival (Ritz, Egberink et al. 2007, Tasker 2018). Whereas, dry FIP usually displays neurological signs (Crawford, Stoll et al. 2017) or ocular signs, which progresses in a few weeks to months and are more chronic (Tasker 2018). The alpha- 1 acid glycoprotein (AGP) in FIP diagnosis Prior to acquired immune response, part of the innate response is the acute phase response (Murata, Shimada et al. 2004, Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). Proteins known as the acute phase proteins (APPs) are then increased in production from hepatocytes and peripheral tissues and then released (Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). These blood proteins can be used to evaluate the innate response to infection, inflammation or trauma (Murata, Shimada et al. 2004, Petersen, Nielsen et al. 2004, Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Eckersall and Bell 2010). With changes by >25% in the serum concentration in response to disease stimulation, APPs are considered useful quantitative biomarkers of diseases- in diagnosis, prognosis, response to therapy, and in general health screening (Eckersall and Bell 2010). In response to inflammations, the serum alpha- 1 acid glycoprotein (AGP) concentration increases as a major acute phase protein in cats (Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Paltrinieri 2008, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011). Studies showed increased serum AGP concentration in cats infected with FIP (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Giordano, Spagnolo et al. 2004, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011). The feline AGP in both serum and peritoneal fluid are known biomarker for FIP (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Giordano, Spagnolo et al. 2004, Eckersall and Bell 2010). In a study conducted, AGP in effusion showed to be the best APP to distinguish between cats with and without FIP (Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016). Although AGP elevations are not specific for FIP, the measurement is helpful in the diagnosis of FIP, and levels >1.5 mg/ml are often observed in FIP cases (Tasker 2018). It was then concluded that the higher levels increase the index of suspicion (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Paltrinieri, Giordano et al. 2007, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011, Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016, Tasker 2018). With difficulty in diagnosing FIP through conventional approaches (Addie, Paltrinieri et al. 2004, Paltrinieri 2008), samples from FIP infected cats showed AGP seemed to be associated with viral antigen and are seen present in large amounts (Paltrinieri, Giordano et al. 2004, Paltrinieri 2008). Nevertheless, AGP plays role in drug-binding, as an immunomodulatory agent, and acts as a plasma transport protein (Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Ceciliani, Ceron et al. 2012, Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). References: Siddell SG. The coronaviridae. London: Plenum Press, 1995 Drechsler, Y., Alcaraz, A., Bossong, F., Collisson, E.W., Diniz, P. (2011), “Feline Coronavirus in Multicat Environments”. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 41(6):1133-69. Addie, D. D., S. Paltrinieri, N. C. Pedersen and s. Secong international feline coronavirus/feline infectious peritonitis (2004). “Recommendations from workshops of the second international feline coronavirus/feline infectious peritonitis symposium.” Journal of feline medicine and surgery 6(2): 125-130. Addie, D. D., S. Toth, G. D. Murray and O. Jarrett (1995). “Risk of feline infectious peritonitis in cats naturally infected with feline coronavirus.” Am J Vet Res 56(4): 429-434. Ceciliani, F., J. J. Ceron, P. D. Eckersall and H. Sauerwein (2012). “Acute phase proteins in ruminants.” J Proteomics 75(14): 4207-4231. Ceron, J. J., P. D. Eckersall and S. Martýnez-Subiela (2005). “Acute phase proteins in dogs and cats: current knowledge and future perspectives.” Vet Clin Pathol 34(2): 85-99. Crawford, A. H., A. L. Stoll, D. Sanchez-Masian, A. Shea, J. Michaels, A. R. Fraser and E. Beltran (2017). “Clinicopathologic Features and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in 24 Cats With Histopathologically Confirmed Neurologic Feline Infectious Peritonitis.” J Vet Intern Med 31(5): 1477-1486.

Breed-related disease: Somali cat

John K Rosembert The Somali cat is often described as a long-haired African cat; a product of a recessive gene in Abyssinian cats, though how the gene was introduced into the Abyssinian gene pool is unknown. It is believed that they originated from Somalia, long lost cousin of the Abyssinian cat; which has origins in Ethiopia. If one judged by appearance, the Somali appears feral, but one look into its eyes and it is clear that this cat has a lot more going on in its head than the average cat. The Somali is so well known for its alertness that the standards for the breed include “alert” in the physical description. The eyes are almond-shaped, and may be green or copper-gold. In size, the Somali is medium to large, muscular and well proportioned, and like its forbearer the Abyssinian, the Somali is elegant yet solidly built. It is a slow developing breed, reaching its full size, maturity, and potential around 18 months. The hair is agouti, or ticked, with anywhere from 4-20 bands of color on each strand. The standard colors for the Somali are red, blue, ruddy, or fawn, but this breed is born in a lot of other colors as well. Silver is one of the colors gaining popularity, for example. The Somali is an active cat who loves to jump and play. In spite of that, she is an easy cat to have in your home. Somalis love people and other animals. Somalis are social cats and like to have some company. This company can be provided by another cat or when people are not at home. The Somali is loving and affectionate and loves to spend time with her parent. While the Somali is a long haired cat, the coat is easy to care for since it is not woolly. A daily brushing as part of play time will keep the Somali’s coat soft and silky. She will reward her groomer with a loving purr. Somalis are active cats and generally will keep their weight under control with compensating exercise. They should have some high perches and cat trees available so they can jump and climb. Some Somalis, like some Abyssinians, can develop a hereditary health issue called pyruvate kinase deficiency that can be a concern, especially if you aren’t cautious about who you buy from. Pyruvate kinase is a key regulatory enzyme in the metabolism of sugar. Cats deficient in PK typically have intermittent anemia. The deficiency can appear in Somalis as young as 6 months and as old as 12 years. The hereditary condition is caused by a recessive gene. A DNA test is available to determine whether a cat is normal, a carrier or affected by PK deficiency. Testing for PK deficiency and breeding away from it will eventually help to eliminate the disease from the breed. Not every PK-deficient cat develops clinical signs, which vary but include lethargy, depression, lack of appetite, and pale gums. The best treatment for PK deficiency is unknown, but it’s still a good idea to have a Somali tested for it. Other problems that may be seen in the breed include a disorder called renal amyloidosis, a neuromuscular condition called myasthenia gravis, and an eye disease called progressive retinal atrophy, which eventually leads to blindness. Source: https://www.hillspet.com/cat-care/cat-breeds/somali http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/somali#health Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somali_cat#/media/File:Blue_Somali_kitten_age_3_months.jpg

Feline NT- proBNP as a cardiac biomarker

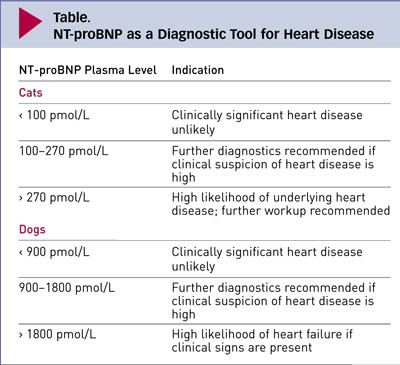

Maigan Espinili Maruquin Feline NT- proBNP The atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) are hormones released into the circulation in response to stimuli. These Natriuretic peptides (NP) are synthesized by cardiomyocytes which regulates body fluid homeostasis and blood pressure (Wilkins, Redondo et al. 1997, Connolly 2010)( Martinez RA, et al., 2009). From preprohormones, NP are processed to prohormones (Blake 2018). The proANP and proBNP, once released, quickly cleaves into separate inactive N-terminal (NT-proANP, NT-proBNP) and active C-terminal (C-ANP, C-BNP) fragments (Oyama 2013, Blake 2018). In humans, ANP has shorter half- life than the BNP (Suga, Nakao et al. 1992, Blake 2018). On the other hand, while C-terminal provides counterbalance to those of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, it has shorter half-life than that of the N-terminal, making NT-proBNP more stable for assay detection (Potter 2011, Oyama 2013, Blake 2018). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) The HCM has a prevalence of around 15% among cats wherein this disease of the myocardium causes abnormal thickening of the walls of the left ventricle (LV) (Paige, Abbott et al. 2009, Abbott 2010, Wagner, Fuentes et al. 2010, Payne, Brodbelt et al. 2015, Luis Fuentes and Wilkie 2017). Some cats experiencing HCM develop congestive heart failure (CHF), arterial thromboembolism (ATE), or sudden cardiac death (SCD) (Payne, Borgeat et al. 2013, Payne, Borgeat et al. 2015, Luis Fuentes and Wilkie 2017). Usually, HCM in felines is detected incidentally on routine veterinary examinations through auscultatory findings including arrhythmias, gallop sounds, or murmurs, while sometimes, detection is from heart failure clinical signs or embolism (Atkins, Gallo et al. 1992, Rush, Freeman et al. 2002, Abbott 2010). Moreover, HCM is considered the most prevalent myocardial disorder in cats (Fox, Liu et al. 1995, Fox, Basso et al. 2007, Paige, Abbott et al. 2009, Fox, Rush et al. 2011). Due to limited sensitivity and specificity of physical examination, electrocardiography (ECG) and thoracic radiography, diagnosing cardiomyopathy has been a challenge (Côté, Manning et al. 2004, Wood and Picard 2004, Schober, Maerz et al. 2007, Harris, Estrada et al. 2017), whereas, the current clinical gold standard used in cats is echocardiography (Harris, Estrada et al. 2017). Although echocardiography has high specificity in diagnosing myocardial disease (Wood and Picard 2004, Fox, Rush et al. 2011), its sensitivity is sometimes limited in detecting HCM (Fox, Rush et al. 2011). The efficacy of treatments for the HCM has limited knowledge. Some agents were suspected to slow the progression of HCM in other breeds of cats, considering the probable existence of genetic heterogeneity in feline HCM. Interventions to speed myocardial relaxation or slow heart rate were also observed in attempt to improve diastolic function. (Abbott 2010). Feline NT- proBNP Assay Table 1. Plasma Levels of Feline NT-proBNP and their indications (https://www.cliniciansbrief.com/article/cardiac-n-terminal-pro-b-type-natriuretic-peptide-assay) There is an increase of interest in the usefulness of cardiac biomarker measurement in veterinary practice (Oyama 2013). In cats, there are available, inexpensive, not requiring advance training cardiac biomarkers for initial screening cardiomyopathy (Luis Fuentes and Wilkie 2017)( Charron P., et al., 2003). The echocardiography has a huge role in feline diagnosis of structural heart disease, however, due to its availability and appropriateness in in emergent circumstances, the use of NT-proBNP assays have been stimulated in differentiating CHF and non- cardiac causes of respiratory distress (Oyama, Boswood et al. 2013). A biomarker is considered clinically useful if it provides information on diagnosis, prognosis, or response to treatment (Oyama 2013). The NT-proBNP in cats can be measured by conducting feline-specific NT-proBNP assay (Singletary, Rush et al. 2012). It has been reported that low NT-proBNP concentration is mostly non- cardiac cause (Oyama 2013) while cats with increased NT-proBNP were reported to have clinically relevant structural heart and elevated concentration suggests CHF (Connolly, Magalhaes et al. 2008, Fox, Oyama et al. 2009, Fox, Rush et al. 2011, Singletary, Rush et al. 2012, Oyama 2013). The NT-proBNP test appears to be not useful for breeding examination (Hsu, Kittleson et al. 2009, Singh, Cocchiaro et al. 2010, Hassdenteufel, Henrich et al. 2013). References: Martinez-Rumayor A, Richards AM, Burnett JC, et al. Biology of the natriuretic peptides. Am J Cardiol 2009; 101:3–8. Charron P, Forissier JF, Amara ME, et al. Accuracy of European diagnostic criteria for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a genotyped population. Int J Cardiol 2003; 90:33–38 Abbott, J. A. (2010). “Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: An Update.” Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice 40(4): 685-700. Atkins, C. E., A. M. Gallo, I. D. Kurzman and P. Cowen (1992). “Risk factors, clinical signs, and survival in cats with a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: 74 cases (1985-1989).” J Am Vet Med Assoc 201(4): 613-618. Blake, R. (2018). “The use of cardiac biomarkers in dogs and cats.” Companion Animal 23(10): 569-577. Connolly, D. J. (2010). “Natriuretic Peptides: The Feline Experience.” Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice 40(4): 559-570. Connolly, D. J., R. J. Magalhaes, H. M. Syme, A. Boswood, V. L. Fuentes, L. Chu and M. Metcalf (2008). “Circulating natriuretic peptides in cats with heart disease.” J Vet Intern Med 22(1): 96-105. Côté, E., A. M. Manning, D. Emerson, N. J. Laste, R. L. Malakoff and N. K. Harpster (2004). “Assessment of the prevalence of heart murmurs in overtly healthy cats.” J Am Vet Med Assoc 225(3): 384-388. Fox, P. R., C. Basso, G. Thiene and B. J. Maron (2007). Spontaneous Animal Models. Arrhythmogenic RV Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia: Recent Advances. F. I. Markus, A. Nava and G. Thiene. Milano, Springer Milan: 69-78. Fox, P. R., S. K. Liu and B. J. Maron (1995). “Echocardiographic assessment of spontaneously occurring feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. An animal model of human disease.” Circulation 92(9): 2645-2651. Fox, P. R., M. A. Oyama, C. Reynolds, J. E. Rush, T. C. DeFrancesco, B. W. Keene, C. E. Atkins, K. A. Macdonald, K. E. Schober, J. D. Bonagura, R. L. Stepien, H. B. Kellihan, T. P. Nguyenba, L. B. Lehmkuhl, B. K. Lefbom, N. S. Moise and D. F. Hogan (2009). “Utility of plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) to distinguish between congestive heart failure and non-cardiac

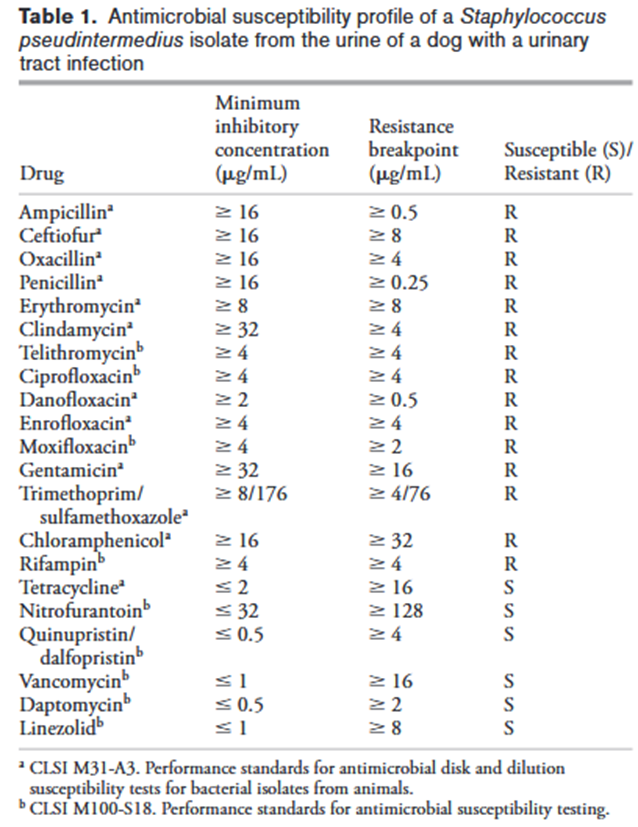

Urinary tract infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in a dog

Joseph E. Rubin and Matthew C. Gaunt Source: Can Vet J. 2011 Feb; 52(2): 162–164. A 16-month-old neutered male pug dog was presented on emergency due to hematuria and pollakiuria of 2-days duration. A urinary tract infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) was diagnosed, following culture and susceptibility testing. The isolated MRSP was susceptible to only tetracycline among commonly used antimicrobials. Treatment with doxycycline led to bacteriological cure and resolution of clinical signs. No presumptive risk factors for acquisition of MRSP were identified in this case indicating that the infection was community acquired.

Breed-related disease: Irish Setter

The Irish Setter is a setter, a breed of gundog, and a family dog. The term Irish Setter is commonly used to encompass the show-bred dog recognized by the American Kennel Club as well as the field-bred Red Setter recognized by the Field Dog Stud Book. It’s not surprising that this handsome redhead comes from Ireland, which is famous for fine and beautiful dogs. The Irish Setter appears to have been developed there in the 18th century, probably the result of combining English Setters, spaniels, pointers, and Gordon Setters. Those first Irish Setters were sometimes called red spaniels — a clue to their heritage, perhaps — or modder rhu, Gaelic for “red dog.” Often, they were white and red instead of the solid dark red we see today. Some, described as “shower of hail” dogs, had red coats sprinkled with small white spots. The Irish Earl of Enniskillen may have started the fad for solid red dogs. By 1812, he would have no other kind in his kennels. Here are some of the most common diseases for Irish Setter Bloat Gastric Dilatation and Volvulus, also known as GDV or Bloat, usually occurs in dogs with deep, narrow chests. This means your Setter is more at risk than other breeds. When a dog bloats, the stomach twists on itself and fills with gas. The twisting cuts off blood supply to the stomach, and sometimes the spleen. Left untreated, the disease is quickly fatal, sometimes in as little as 30 minutes. Your dog may retch or heave (but little or nothing comes out), act restless, have an enlarged abdomen, or lie in a prayer position (front feet down, rear end up). Allergies In humans, an allergy to pollen, mold, or dust makes people sneeze and their eyes itch. In dogs, rather than sneeze, allergies make their skin itchy. We call this skin allergy “atopy”, and Setters often have it. Commonly, the feet, belly, folds of the skin, and ears are most affected. Symptoms typically start between the ages of one and three and can get worse every year. Licking the paws, rubbing the face, and frequent ear infections are the most common signs. Neurologic Problems Several neurologic diseases can afflict Irish Setters. Symptoms of neurological problems can include seizures, imbalance, tremors, weakness, or excess sleeping. A genetically linked neurological condition that could occur in your Irish setter causes a wobbly, drunken gait. This condition, known as wobbler disease or wobbler syndrome, happens because there is a narrowing of the vertebrae in the neck, which pinches the spinal cord and associated nerves. There are three types of seizures in dogs: reactive, secondary, and primary. Reactive seizures are caused by the brain’s reaction to a metabolic problem like low blood sugar, organ failure, or a toxin. Secondary seizures are the result of a brain tumor, stroke, or trauma. If no other cause can be found, the disease is called primary, or idiopathic epilepsy. This problem is often an inherited condition, with Irish Setters commonly afflicted. If your friend is prone to seizures, they will usually begin between six months and three years of age. Bleeding Disorders There are several types of inherited bleeding disorders which occur in dogs. They range in severity from very mild to very severe. Many times a pet seems normal until a serious injury occurs or surgery is performed, and then severe bleeding can result. Irish Setters are particularly prone to some relatively rare diseases of the blood. Source: https://douglasanimalhospital.com/client-resources/breed-info/irish-setter/ Photo credit : https://www.dogbreedinfo.com/irishsetter.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Setter

Breed-related disease: Cornish Rex

A Cornish Rex is a breed of domestic cat. The Cornish Rex has no hair except for down. Most breeds of cat have three different types of hair in their coats: the outer fur or “guard hairs”, a middle layer called the “awn hair”; and the down hair or undercoat, which is very fine and about 1 cm long. Cornish Rexes only have the undercoat. They are prone to hair loss and many will develop a very thin coat or even go bald over large parts of their body. The curl in their fur is caused by a different mutation and gene than that of the Devon Rex. The breed originated in Cornwall, Great Britain. The Cornish Rex is an athletic cat and will maintain her ideal weight if provided with enough space for exercise. Thanks to the close-lying nature of the coat, you can easily tell if a Cornish is getting too heavy. The Cornish Rex is agile and loves to jump, run, and play. When she is playing, she can appear to be inexhaustible. She should have interactive exercises as well. The Cornish Rex becomes involved with her parent. She loves to be right next to her parent and must have some time together every day. Many Cornish Rex will do anything to be with their parents and will even learn to walk on a lead in order to spend more time together. In general, they love being handled by their parents. Here are some health issues your Cornish Rex is prone at: Arterial Thromboembolism Cats with heart disease may develop blood clots in their arteries known as FATE (feline aortic thromboembolisms). Blood clots most commonly become lodged just past the aorta, the large blood vessel that supplies blood from the heart to the body, blocking normal blood flow to the hind legs. When this happens, one or both hind legs may become paralyzed, cold, or painful. Blood Type Although we hate to think of the worst happening to our pets, when disaster strikes, it’s best to be prepared. One of the most effective life-saving treatments available in emergency medicine today is the use of blood transfusions. If your cat is ever critically ill or injured and in need of a blood transfusion, the quicker the procedure is started, the better the pet’s chance of survival. Patellar Luxation The stifle, or knee joint, is a remarkable structure that allows a cat to perform amazing feats of agility like crouching, jumping, and pouncing. One of the main components of the stifle is the patella or kneecap, and the medical term luxation means “being out of place”. Thus, a luxating patella is a kneecap that slips off to the side of the leg because of an improperly developed stifle. A cat with a luxating patella may not show signs of pain or abnormality until the condition is well advanced; signs of this condition appear gradually and can progress to lameness as the cat grows older. Hypotrichosis Hypotrichosis is caused by a recessive genetic defect found in several cat breeds, including Cornish Rexes. This disease causes thinning of the hair or balding, which tends to develop in patterns or patches on the torso and head. A kitten can be born with symmetrical hair loss, or thinning of hair may ensue shortly after birth. In time, affected areas may develop additional pigmentation or thickened skin. Sources: https://valleyanimalhospitalllc.com/client-resources/breed-info/cornish-rex/ Photo credit : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornish_Rex

KNOWING THE THREAT OF CANINE BABESIOSIS

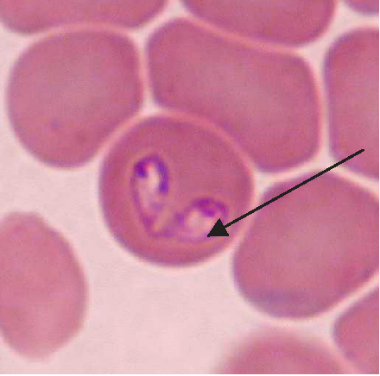

Maigan Espinili Maruquin Our pets are members of our family. And like the other members, they need care, love, and attention. We spend most of our time in the work, school, and other daily activities we have, which lessens the time we spend with our pets. However, we should also listen to our companions who stays at home. Attend to their needs, specially their health. As important as the humans, dogs also need regular medical checks to make sure that they are living a happy and healthy life. One of the diseases you should be cautious of when you have a dog companion are those caused by parasites. For both domestic and wild canines, canine babesiosis is an important widespread disease. The disease is caused by single-celled microorganisms (protozoa) belonging to the Babesia family. Babesia parasites are primarily spread by the bite of an infected tick. The distribution of the canine Babesia species are greatly affected by the presence of tick vector species in the area. Babesia infecting dogs are morphologically classified into forms of large, including B. canis, B. volgeli, B. rossi, and small, including B. gibsoni, both exhibiting a worldwide distribution. Among Babeisa species infecting dogs, B. gibsoni has been recognized as an important pathogen that affects dogs in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Europe, and many areas of the United States. The babesiosis is associated mainly in haemolytic anaemia or the destruction and breaking down of the red blood cells. B. gibsoni can cause hyperacute, acute, and chronic infections. Clinical signs present are ambiguous, which includes depression, lethargy, fever, weakness, vomiting, pale gums and anorexia. However, other specific signs include dark coloration of the urine, neurological dysfunction, respiratory failure, jaundice, and sometimes presence of bleeding diatheses. Severe cases may lead to organ failure and death. However, some cases during the initial stages appear to be unnoticed to the pet owners. On the other hand, chronic stages often make the dog a carrier of the organism and becomes asymptomatic, and for how long will a dog be a carrier is unknown. How do dogs get infected with babesiosis? The Babesia species resides in its first host, the tick vector. Dogs become infected when ticks feed for 2 to 3 days and release sporozoites, from the salivary gland, into the circulation of dogs. Inside the host, sporozoites start to invade red blood cells, and replicate via binary fission, which produces merozoites to further invade other red blood cells. Ticks become infected with merozoites during feeding, and sexual reproduction of Babesia’s life cycle completes within the ticks. In addition, transmission can also occur through transfusion of infected blood, transplacental transmission (to unborn puppies in the uterus of their mothers), or direct blood-blood contact during fighting. How is babesiosis diagnosed? Canine babesiosis is historically identified based on the observation of the parasite within red blood cells using light microscope. Infection of large or small form of Babesia can be morphagically identified, if enough parasites present in the blood, in the blood smear. Other diagnostic tests detecting antigen include FA (fluorescent antibody) staining of the organism and PCR (polymerase chain reaction) detecting nucleic acid of the Babesia. The PCR test has the advantage in that it can identify all four species of Babesia, but requires trained persons to run it. Serologic or antibody testing may also be performed to see the presence of the parasite. Antibody reaction to the Babesia infection can be measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) in the lab. In addition, a lateral flow immunochromatographic test (or rapid test) has been developed to provide a fast and in-site assay to detect the antibody of dogs infected with B. gibsoni. This rapid test has been commonly assisting the veterinarians for fast diagnosis. Disease Management and Prevention The treatment of an infected dog consists of three components: antiprotozoal treatment of babesiosis, blood transfusions to treat severe anaemia, and supportive therapies for the complications and metabolic derangements. Meanwhile, as a pet owner, regular control of the tick vectors by routinely dipping or spraying pets or using tick collars or spot-on preparations is the only effective way of preventing this disease in most parts of the world. Ticks,if founed on your pets, shouldn’t be squeezed, crushed or twisted to avoid the parasite from being expelled. Removing it properly shall be done or ask the assistance of your veterinarians. To take the ticks off your dog, tick’s mouth should be grasped as close to the skin as possible using forceps. Tick’s mouth shall be removed as much as possible. Afterwhich, make sure to clean the tick bitten area with soap and water or using mild antibacterial wound cleanser. In addition, preventing dogfighting as well as direct blood contact by using sterilized instruments during tail docking and ear cropping procedures and when administering injections are critical. Moreover, a vaccine against B. canis has become commercially available in some countries. You may check with your pet’s veterinarians prior to visiting endemic areas with your dogs. Fig. 1. Two pear-shaped Babesia canis organisms in an erythrocyte. (Duh et al., 2004) Fig. 2. Babesia gibsoni in erythrocytes in a blood smear stained with modified Wright technique. (Trotta et al., 2009) Chauvin A., Moreau E., Bonnet S., Plantard O. & Malandrin L. Babesia and its hosts: adaptation to long-lasting interactions as a way to achieve efficient transmission. 2009. Vet. Res., 40 (2), 37.64. Duh D, Tozon N, Petrovec M, Strasek K, Avsic-Zupanc T. Canine babesiosis in Slovenia: molecular evidence of Babesia canis canis and Babesia canis vogeli. 2004. Vet Res. 35(3):363-8. Refer Conrad P., Thomford J., Yamane I., Whiting J., Bosma L., Uno T., Holshuh H.J. & Shelly S. Hemolytic anemia caused by Babesiagibsoni infection in dogs. 1991. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 199 (5): 601–605. Trotta M, Carli E, Novari G, Furlanello T, Solano-Gallego L. Clinicopathological findings, molecular detection and characterization of Babesia gibsoni infection in a sick dog from Italy. 2009. Vet Parasitol. 165(3-4):318-22.

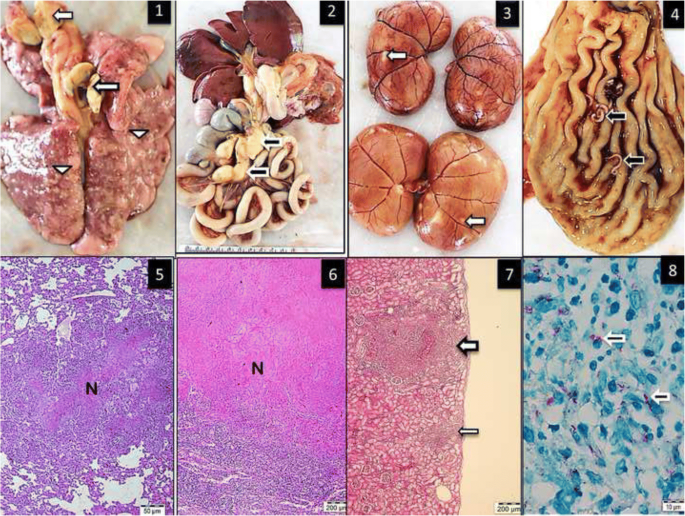

Case report: systemic tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis in a cat- Abstract

Source: https://bmcvetres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12917-018-1759-7 Mycobacterium bovis was isolated from the lungs, bronchial and gastrointestinal lymph nodes, kidney and liver of a 5-year-old stray male cat. The isolate was confirmed as M. bovis using the Genotype MTBC assay (Hain Lifescience, Germany), which allows differentiation of species within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. The Systemic tuberculosis was diagnosed via postmortem examination of the cat. Pathological changes included multifocal to coalescing granulomatous inflammation in the lungs, liver, lymph nodes and kidneys. Infection by immunosuppressive viral pathogens including feline herpes virus-1, feline immunodeficiency virus and feline parvovirus virus were ruled out by polymerase chain reaction assay (PCR). The isolated M. bovis was susceptible to isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampicin or streptomycin. Unlike previous cases of feline tuberculosis in Turkey, this case report details the first case of feline tuberculosis in Turkey for which the causative agent (M. bovis) was confirmed with bacteria isolation, morphological evaluation, molecular characterization and antibiotic sensitivity. Figure Multifocal granulomatous pneumonia (arrowhead) and diffuse lymphadenitis (arrow) of tracheobronchial lymph nodes. 2. Diffuse, severe lymphadenitis in mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow). 3. Multifocal granulomatous nephritis. 4. Gastric worms on the mucosal surface (arrows). 5.6.7. Granulomatous pneumonia (5) with necrosis (N), lymphadenitis (6) and necrosis and nephritis (7) with granulomas (arrows), HE. 8. Acid-fast microorganisms in the cytoplasm of epithelioid macrophages (arrows), ZN

Breed-related disease: Saint Bernard

The St. Bernard or St Bernard is a breed of very large working dog originated in Switzerland along with several other breeds, including the Bernese Mountain Dog, Entlebuch Cattle Dog, Appenzell Cattle Dog, and Greater Swiss Mountain Dog. They probably were created when dogs native to the Alps were crossed with Mastiff-type dogs that came with the Roman army during the time of the emperor Augustus. By the first millennium CE, dogs in Switzerland and the Alps were grouped together and known simply as Talhund” (Valley Dog) or “Bauernhund” (Farm Dog). The Saint Bernard is one of the most popular giant breeds. Its powerful and muscular build contrasts the wise, calm expression. The breed has either long or short hair, ranging in color from a deep to a more yellowed brown, with white markings always present. Even though the Saint Bernard is not very playful, it is patient, gentle, and easy-going with children. It is willing to please and shows true devotion to its family. Sometimes the dog displays its stubborn streak. The Saint Bernard breed, which has a lifespan of 8 to 10 years, may suffer from major health problems such as: Hip Dysplasia: This is a heritable condition in which the thighbone doesn’t fit snugly into the hip joint. Some dogs show pain and lameness on one or both rear legs, but you may not notice any signs of discomfort in a dog with hip dysplasia. Entropion: This defect, which is usually obvious by six months of age, causes the eyelid to roll inward, irritating or injuring the eyeball. One or both eyes can be affected. If your Saint has entropion, you may notice him rubbing at his eyes. The condition can be corrected surgically. Epilepsy: This disorder causes mild or severe seizures. Epilepsy can be hereditary; it can be triggered by such events as metabolic disorders, infectious diseases that affect the brain, tumors, exposure to poisons, or severe head injuries; or it can be of unknown cause (referred to as idiopathic epilepsy). Osteochondrosis; is another inherited orthopedic condition that can affect Saints and many other breeds. It’s a defect in the formation of growing cartilage that causes it to fragment. It usually appears in dogs younger than 1 year. Sources: https://dogtime.com/dog-breeds/saint-bernard#/slide/1 Photo credit : http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/saint-bernard#health

Breed-related disease: Savannah Cat

The Savannah cat is the largest of the cat breeds. A Savannah cat is a cross between a domestic cat and a serval, a medium-sized, large-eared wild African cat. The unusual cross became popular among breeders at the end of the 1990s, and in 2001 The International Cat Association (TICA) accepted it as a new registered breed. In May 2012, TICA accepted it as a championship breed. Some states restrict the ownership of the Savannah to the later filial ratings. A great deal of a Savannah’s personality may depend on how close they are to their F1 cross. A Savannah can be black, brown spotted tabby, black silver spotted tabby or black smoke. Black Savannahs are solid black but may have faint “ghost spots” that can be seen beneath the black color. Some are very social and friendly with new people, while others may run and hide or revert to hissing and growling when seeing a stranger. Savannahs have strong hunting instincts and love to climb and jump. Early socialization is crucial to their development. Well socialized Savannah’s can be affectionate and playful members of the family. This guide contains general health information important to all felines as well as information on genetic predispositions for Savannahs. Here we gathered some of the most common diseases in Savannah Heart Disease Cardiomyopathy is the medical term for heart muscle disease, either a primary inherited condition or secondary to other diseases that damage the heart. The most common form called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, is a thickening of the heart muscle often caused by an overactive thyroid gland. Arterial Thromboembolism Cats with heart disease may develop blood clots in their arteries known as FATE (feline aortic thromboembolisms). Blood clots most commonly become lodged just past the aorta, the large blood vessel that supplies blood from the heart to the body, blocking normal blood flow to the hind legs. When this happens, one or both hind legs may become paralyzed, cold, or painful. FLUTD When your cat urinates outside the litter box, you may be annoyed or furious, especially if your best pair of shoes was the location chosen for the act. But don’t get mad too quickly—in the majority of cases, cats who urinate around the house are sending signals for help. Although true urinary incontinence, the inability to control the bladder muscles, is rare in cats and is usually due to improper nerve function from a spinal defect, most of the time, a cat that is urinating in “naughty” locations is having a problem and is trying to get you to notice. What was once considered to be one urinary syndrome has turned out to be several over years of research, but current terminology gathers these different diseases together under the label of Feline Lower Urinary Tract Diseases, or FLUTD. Allergies/Atopy In humans, an allergy to pollen, mold, or dust makes people sneeze and their eyes itch. In cats it makes the skin itchy. We call this form of allergy “atopy.” Commonly, the legs, belly, face, and ears are very likely to have this problem. Symptoms typically start between the ages of one and three and can get worse every year. Source: https://aubreyamc.com/feline/savannah/ Photo Credit : https://animalhealthcenternh.com/client-resources/breed-info/savannah/ http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/savannah