Table of Contents

Trinh Mai Nguyen Tang

1. Introduction

Feline panleukopenia (FP), commonly referred to as feline distemper, is a globally significant and often fatal infectious disease of cats caused by feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Domestic cats are considered the primary host of the virus. Taxonomically, FPV is a non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus belonging to the family Parvoviridae, genus Protoparvovirus, and species Carnivore protoparvovirus 1. Infection with FPV results in feline leukopenia disease and is characterized by high contagiousness and substantial lethality in susceptible feline populations.

The existence of FPV has been recognized for over a century. The disease was first described in cats in the early twentieth century and formally reported in France in 1928 by Verge and Christoforoni. Since that time, FPV has become endemic worldwide, with disease incidence often following a distinct seasonal pattern. Reported cases typically increase from early summer through autumn, with peak prevalence occurring during July, August, and September.

A major challenge in FPV control lies in the virus’s exceptional environmental durability and resistance to inactivation. As a non-enveloped virus, FPV is highly resistant to many commonly used chemical disinfectants, including alcohols, iodine-based products, and quaternary ammonium compounds, despite frequent label claims of virucidal activity. FPV can persist in contaminated environments for months or even years, contributing to repeated exposure and reinfection risks. Effective environmental decontamination therefore requires the use of strongly oxidizing disinfectants, such as a 1:32 dilution of household bleach (sodium hypochlorite), potassium peroxymonosulfate (for example, Virkon at 1:100 dilution), or accelerated hydrogen peroxide formulations.

From a clinical perspective, FPV remains a major concern due to its high transmissibility and elevated mortality rates, particularly in unvaccinated cats and young kittens. The virus exhibits a marked tropism for rapidly dividing cells, including those in the bone marrow, lymphoid tissues, and intestinal crypt epithelium. This selective cellular targeting leads to profound panleukopenia, severe gastroenteritis characterized by vomiting, dehydration, and, in some cases, hemorrhagic diarrhea, as well as significant immunosuppression. In kittens and inadequately vaccinated cats, mortality rates frequently exceed 90%. The combination of extreme environmental persistence, high infectivity, and severe clinical outcomes makes FPV a persistent and serious threat, particularly in high-density settings such as animal shelters, where outbreaks can result in widespread morbidity, mortality, and substantial operational challenges.

2. Transmission and Clinical Signs of FPV

2.1 Transmission Pathways and Cellular Entry

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) is transmitted primarily via the fecal–oral route. Infection occurs when susceptible cats ingest viral particles through contaminated food, water, fomites, or contact with infected secretions. Because of the virus’s remarkable environmental stability, indirect transmission via contaminated cages, litter boxes, bedding, transport carriers, and human hands or clothing plays a major role in disease spread, particularly in high-density environments.

At the cellular level, FPV initiates infection by binding to the feline transferrin receptor (fTfR) on the host cell surface, which facilitates viral entry and internalization [6–7]. This receptor-mediated process largely determines host specificity and tissue tropism and explains the virus’s predilection for rapidly dividing feline cells.

2.2 Pathogenesis and Tissue Tropism

FPV exhibits a strong tropism for rapidly proliferating cells, a hallmark feature of parvoviral infections. Previous studies have demonstrated that the virus replicates predominantly in small intestinal crypt epithelial cells and lymphoid cells [8–9]. Viral replication within these tissues disrupts normal cell turnover and immune function.

In the gastrointestinal tract, destruction of crypt epithelial cells leads to villous collapse, impaired absorption, and breakdown of the intestinal barrier. Concurrently, infection of lymphoid tissues and bone marrow results in severe leukopenia, compromising innate and adaptive immune responses. Hemorrhage within the small intestine and stomach contributes to the development of hemorrhagic diarrhea, a characteristic and often life-threatening manifestation of FPV infection [10].

2.3 Gross Lesions and Organ Involvement

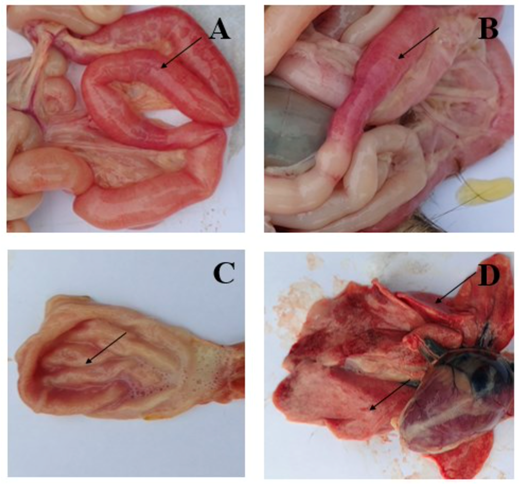

Gross pathological findings in FPV-infected cats reflect the systemic nature of the disease. In a pathological study reported by Yen et al. (2021), examination of eight FPV-infected cats revealed small intestinal congestion in 100% of cases, with intestinal mucosal ulceration observed in 75% of the animals (Figure 1A–B). Gastric congestion was present in 75% of cases (Figure 1C), while mild pneumonia was detected in 25% of cats (Figure 1D).

Additional lesions reported included enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes and splenic infarction, consistent with widespread lymphoid depletion and vascular compromise [10]. These findings underscore the multisystemic involvement of FPV and help explain the rapid clinical deterioration observed in severe cases.

Figure 1. Symptoms of FPV infection in cats. A, B: Intestinal congestion with scattered or intermittent bleeding. C: Congested stomach containing large volumes of fluid. D: Mild pneumonia.

2.4 Clinical Progression and Systemic Effects

The pathological changes induced by FPV give rise to a characteristic progression of clinical signs. Early manifestations often include anorexia, lethargy, fever, vomiting, and deterioration of coat condition. As the disease advances, affected cats frequently develop profuse diarrhea, severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and hypoglycemia.

In advanced stages, disruption of the intestinal barrier and profound immunosuppression predispose cats to bacterial translocation, sepsis, and endotoxemia. Without timely and intensive supportive treatment, these systemic complications can lead to rapid clinical decline and death [12–15]. The severity and speed of disease progression are particularly pronounced in kittens and immunologically naïve cats.

2.5 Neurological Manifestations in Kittens

In addition to gastrointestinal and hematological effects, FPV infection can result in neurological abnormalities, particularly when infection occurs in utero or during early neonatal development. Reported central nervous system lesions include cerebellar hypoplasia and hydrocephalus, which arise from viral interference with neuronal precursor cell division.

Kittens affected by cerebellar hypoplasia may survive the acute infection but exhibit permanent neurological deficits, such as ataxia, intention tremors, and impaired coordination. These manifestations are non-progressive but irreversible and represent an important long-term consequence of early FPV exposure.

2.6 Incubation Period and Viral Shedding

The incubation period of FPV infection is typically 4 to 6 days, although clinical onset may vary depending on viral dose, host immunity, and age. During active infection, cats can shed large quantities of virus in feces for up to 43 days, contributing significantly to environmental contamination and onward transmission.

Notably, FPV has been reported to persist in tissues such as the lungs and kidneys for more than one year, even after clinical recovery. This prolonged viral persistence further complicates control efforts and reinforces the importance of stringent biosecurity and disinfection protocols following outbreaks.

3. Age Susceptibility and Maternally Derived Antibodies (MDAs)

3.1 High-Risk Age Groups and Mortality

Kittens represent the population at highest risk for severe disease and mortality following infection with feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Although cats of all ages may become infected if unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated, clinical disease is most frequently observed in kittens under one year of age.

The highest incidence of FPV-associated morbidity and mortality occurs in kittens between two and five months of age, with infection most commonly reported in those three to five months old. During this period, maternally derived antibodies (MDAs) have declined to subprotective levels, leaving kittens highly susceptible to infection. In this age group, mortality rates approaching 90% have been reported, particularly in the absence of timely supportive care and appropriate biosecurity measures.

3.2 Role of Colostrum and Passive Immunity

Maternally derived antibodies (MDAs) provide passive immune protection to kittens during the early postnatal period. These antibodies are transferred primarily through colostrum, the first milk produced by the queen after parturition. Passive immunity acquired via colostrum plays a critical role in protecting neonates during the initial weeks of life, before their own immune systems become fully functional.

The degree and duration of passive immunity in kittens depend on several factors, including the concentration of specific antibodies present in the queen’s colostrum, the volume and quality of colostrum ingested, and the timing of nursing relative to birth. Systemic absorption of colostral antibodies occurs during a limited window, generally within the first 24 hours after birth, after which intestinal permeability to immunoglobulins rapidly declines.

Globally, it is estimated that more than 95% of the passive antibodies required by newborn puppies and kittens are acquired through colostrum. Consequently, inadequate colostrum intake can result in insufficient passive immunity and increased vulnerability to infectious diseases such as FPV.

3.3 Immunological Gap and Vaccine Interference

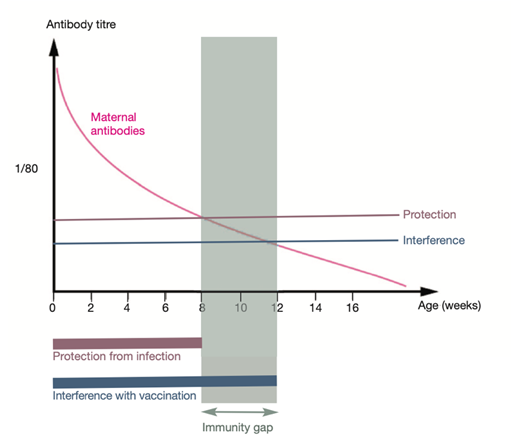

Although MDAs provide early protection, this immunity is temporary. Antibody levels typically persist for 6 to 8 weeks, after which they gradually decline. This decline creates a critical period known as the “immunity gap.”

The immunological gap refers to the interval during which MDA levels are too low to protect against FPV infection but remain sufficiently high to interfere with vaccine-induced immune responses. This period most commonly occurs between 8 and 12 weeks of age.

3.4 Vaccine Response and Seroconversion

The presence of maternally derived antibodies has a significant impact on vaccination efficacy in kittens.

When MDA titers are ≥1:10, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays, administration of modified live virus (MLV) vaccines is generally not recommended, as circulating antibodies can neutralize the vaccine virus and prevent seroconversion. Importantly, even antibody levels below the detection limits of some serological assays may still interfere with effective vaccine-induced immunity.

Evidence indicates that kittens lacking MDAs develop robust and long-lasting antibody titers following MLV vaccination, whereas kittens with residual MDAs exhibit reduced or absent seroconversion. For this reason, MLV vaccines are often favored in high-risk environments, as they are believed to overcome MDA interference earlier and induce a more rapid onset of protective immunity compared with inactivated vaccines.

Despite adherence to recommended vaccination schedules, vaccine failure remains a recognized concern. In one study, 36.7% of kittens failed to seroconvert despite receiving three vaccine doses, and a substantial proportion still exhibited detectable MDAs at 8 and 12 weeks of age. These findings highlight that protective immunity is not achieved in a significant subset of kittens following standard vaccination protocols and underscore the importance of continued biosecurity, diagnostic vigilance, and population-level disease control strategies.

Figure 2. The immunity gap and maternally derived antibodies (MDAs)

During this time, kittens are particularly vulnerable, as they may become infected while failing to mount an adequate immune response following vaccination.

This phenomenon represents a major challenge in FPV prevention and explains why infection may occur even in kittens that have begun vaccination protocols.

4. Diagnosis of Feline Parvovirus (FPV)

4.1 Diagnostic Challenges and Differential Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) infection presents several clinical challenges, largely due to the non-specific nature of early clinical signs and significant overlap with other feline diseases. FPV may be difficult to distinguish clinically from feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection, feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infection, and pancreatitis, as well as other infectious and non-infectious gastrointestinal disorders. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the severity of infection, host immune status, and disease stage.

FPV typically presents with lethargy, anorexia, pyrexia, and vomiting, which are non-specific signs common to many systemic illnesses. In peracute infections, cats may die suddenly with minimal or no preceding clinical signs, further complicating timely diagnosis. As the disease progresses, vomiting and, in some cases, diarrhea may develop. Importantly, the absence of leukopenia does not exclude FPV, as one study reported leukopenia in only approximately 65% of clinically affected cats.

A comprehensive differential diagnosis is therefore essential and should include:

- Viral infections: FeLV, FIV, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), feline enteric coronavirus, and feline calicivirus

- Bacterial and parasitic infections: Salmonellosis, severe gastrointestinal parasitism, and enteric bacterial infections

- Non-infectious conditions: Pancreatitis, gastrointestinal foreign bodies, inflammatory bowel disease, and congenital central nervous system defects (particularly in kittens presenting with neurological signs)

4.2 FPV Detection Using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is widely regarded as the gold standard for confirming FPV infection due to its high analytical sensitivity and specificity.

PCR assays can detect FPV DNA in feces, whole blood, and tissue samples, making them highly versatile for diagnostic use. Compared with immunochromatographic strips, hemagglutination assays, and ELISA-based tests, PCR offers superior sensitivity, particularly in cases with low viral shedding.

Key considerations for PCR-based FPV diagnosis include:

- Target genes: Most real-time PCR (qPCR) assays target the viral VP2 gene and are capable of detecting both FPV and closely related canine parvovirus (CPV). Some assays can further differentiate between vaccine strains and field isolates.

- Quantitative value: qPCR allows for estimation of viral load. For example, one reference laboratory defines a positive result as a cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤26, corresponding to ≥1.59 × 10⁶ viral DNA copies per gram of sample.

- Limitations: PCR detects viral nucleic acid from both viable and non-viable virus. Consequently, a positive PCR result does not necessarily indicate the presence of infectious virus, particularly after the acute shedding phase or following recent vaccination.

- Practical considerations: PCR testing is relatively expensive, requires specialized laboratory facilities, and may result in a 1–3 day delay before results are available.

4.3 FPV Detection Using Rapid Antigen Test Kits

Rapid point-of-care (POC) antigen tests are widely used in clinical practice and shelter environments for the detection of feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) due to their speed, simplicity, and suitability for in-clinic decision-making. These assays are designed to detect FPV-specific antigens in fecal samples, vomitus, or rectal swabs from cats with compatible clinical signs.

Bioguard’s FPV Antigen Rapid Test is an immunochromatographic assay developed for the qualitative detection of FPV antigen in feline samples. The test is designed for ease of use in clinical settings and provides results within a short time frame. Under evaluated conditions, the assay has demonstrated a reported sensitivity and specificity of 92.54%, supporting its utility as a rapid screening tool for suspected FPV infection.

Despite their clinical value, several limitations must be considered when interpreting results from FPV rapid antigen tests:

- Sensitivity limitations: The diagnostic sensitivity of rapid antigen tests may vary depending on viral load, stage of infection, and viral shedding dynamics. Reduced sensitivity has been reported in cases with low fecal viral concentrations.

- False-negative results: A negative rapid test result does not definitively exclude FPV infection, particularly in kittens or cats with strong clinical suspicion. In such cases, confirmatory testing using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or repeat testing is strongly recommended.

- High specificity: Rapid FPV antigen tests generally exhibit high specificity, meaning positive results, including weak positive reactions, are considered reliable indicators of infection in clinically affected cats.

- Sample type considerations: Test performance may be influenced by sample selection. Fecal samples or vomitus collected during peak viral shedding are generally preferred to optimize diagnostic yield.

- Post-vaccination interference: Rare false-positive results may occur following administration of modified live virus (MLV) FPV vaccines, as vaccine-derived antigen may be detectable for up to approximately 14 days post-vaccination.

4.4 Hematological Findings

Hematological abnormalities are a hallmark of FPV infection and provide valuable diagnostic and prognostic information. One of the most characteristic findings is marked leukopenia, reflecting the virus’s tropism for rapidly dividing hematopoietic and lymphoid cells.

White blood cell (WBC) counts in FPV-infected cats are commonly below 3,000 cells/mm³ and may decline to less than 200 cells/mm³ in severe cases. This profound leukopenia underlies the term panleukopenia and contributes significantly to immunosuppression and susceptibility to secondary infections.

Key hematological features include:

- Panleukopenia: Reduction across multiple leukocyte lineages, supporting diagnosis when combined with compatible clinical signs

- Neutropenia and lymphopenia: Neutropenia typically develops earlier, and total WBC counts ≤2,000 cells/µL (or <1,000/µL) are associated with a poor prognosis

- Additional abnormalities: Thrombocytopenia is common and may progress toward disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC); mild anemia is frequently observed

- Recovery indicators: Surviving cats often demonstrate clinical improvement accompanied by rebound leukocytosis or neutrophilia and restoration of appetite

5. Prevention and Treatment of Feline Panleukopenia Virus (FPV)

5.1 Environmental Control and Biosecurity

Effective control of feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) relies heavily on rigorous environmental management and biosecurity, due to the virus’s exceptional resistance to physical and chemical inactivation. FPV is a non-enveloped virus capable of surviving in contaminated environments for months to years, making environmental persistence a major driver of ongoing transmission.

Routine cleaning of animal housing, shelters, feeding equipment, and fomites is essential following confirmed or suspected FPV infection. Infected cats must be strictly isolated to prevent transmission and outbreak escalation, particularly in high-density environments such as shelters, catteries, and breeding facilities.

FPV is resistant to many commonly used disinfectants, including alcohols, iodine-based compounds, and quaternary ammonium disinfectants, which have repeatedly been shown to be ineffective against parvoviruses despite label claims. As a result, strict disinfection protocols using strongly oxidizing agents are required.

Recommended disinfectants include:

- Sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) diluted 1:32, applied to pre-cleaned surfaces with a minimum contact time of approximately 10 minutes

- Accelerated hydrogen peroxide (AHP), which retains activity in the presence of limited organic matter and is suitable for porous surfaces such as wood and carpet

- Potassium peroxymonosulfate (e.g., Virkon), used according to manufacturer guidelines

Because FPV is shed in feces for at least 14 days after clinical recovery, prolonged isolation is required to reduce environmental contamination. Indirect transmission via fomites and personnel represents a significant risk; therefore, barrier nursing practices are essential. These include the use of dedicated personnel, gloves, gowns, footwear, and equipment for infected areas, along with strict separation between infected, exposed, and unexposed populations.

5.2 Treatment Principles

Feline panleukopenia is a life-threatening disease with no specific antiviral cure. Treatment is therefore entirely supportive and symptomatic, aimed at maintaining physiological stability while the cat’s immune system clears the infection. Early recognition and aggressive supportive care are critical determinants of survival.

Key components of FPV treatment include:

- Fluid Therapy: Aggressive intravenous administration of balanced isotonic crystalloids, such as Lactated Ringer’s Solution (LRS), often supplemented with potassium, is essential to correct dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and hypovolemic shock.

- Antiemetic Therapy: Agents such as maropitant or ondansetron are used to control vomiting, reduce fluid loss, improve patient comfort, and facilitate early nutritional support.

- Antimicrobial Therapy: Broad-spectrum parenteral antimicrobials are mandatory to prevent or treat secondary bacterial infections and sepsis, which arise from gastrointestinal barrier disruption and profound leukopenia. Coverage should target gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes, which represent the most significant pathogens in this context.

- Nutritional Support: Early enteral nutrition is strongly recommended when vomiting is controlled, as maintaining gastrointestinal integrity reduces bacterial translocation and improves outcomes. Parenteral nutrition may be considered if enteral feeding is not tolerated.

- Blood and Plasma Transfusions: Administration of fresh-frozen plasma can help maintain oncotic pressure, supply clotting factors, and provide passive anti-FPV antibodies. Whole blood transfusions are indicated in cases of severe anemia.

- Immunomodulatory Therapy: Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF), such as filgrastim, has been evaluated as an adjunctive therapy to stimulate neutrophil recovery. While some studies report improved leukocyte counts and potential survival benefits, others demonstrate no significant impact on mortality, and its routine use remains controversial.

Reported survival rates for hospitalized cats range from 20% to 51%. Poor prognostic indicators include severe leukopenia (WBC <1,000/µL), hypokalemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypothermia, and low body weight. Cats that survive beyond five days after the onset of clinical signs generally have a favorable chance of recovery.

5.3 Vaccination as Primary Prevention

Vaccination is the most effective and reliable method for preventing FPV infection and is classified as a core vaccination for all cats worldwide.

Modified live virus (MLV) vaccines are widely used due to their ability to induce rapid and robust immunity. However, MLV vaccines must not be administered to:

- Kittens younger than 4 weeks of age

- Immunocompromised cats

- Pregnant queens, due to the risk of fetal infection and neurological defects such as cerebellar hypoplasia

Vaccine type and immune response

- MLV vaccines provide a rapid onset of immunity and are more effective at overcoming maternally derived antibody (MDA) interference than inactivated vaccines. In cats without MDAs, protective immunity can develop within 72 hours of exposure.

- Killed (inactivated) vaccines require multiple doses and provide slower immune protection. They are preferred for pregnant queens in low-risk environments.

Kitten vaccination protocols

- Maternal antibodies acquired via colostrum can neutralize vaccine virus, creating an “immunity gap.”

- WSAVA guidelines recommend initiating core vaccination (FPV, FHV-1, FCV) at 6–8 weeks of age, with boosters every 2–4 weeks until at least 16 weeks of age.

- The final vaccine dose at ≥16 weeks is the most critical for ensuring effective seroconversion.

- A booster at 6 months or 1 year of age is recommended to capture kittens that failed to respond during the primary series.

- In high-risk environments, vaccination may begin as early as 4–6 weeks of age, with boosters every 2 weeks until 20 weeks of age or until the cat leaves the facility.

Adult revaccination

- Following successful immunization, cats develop long-lasting immunity, often persisting for 7 years or longer.

- For low-risk adult cats, revaccination no more frequently than every 3 years is recommended by WSAVA.

6. Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV)

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is one of the most common and clinically significant infectious diseases affecting cats worldwide. From a veterinary perspective, FIV is particularly important because infection results in a persistent, lifelong viral state that progressively impairs immune function. Over time, this immunodeficiency predisposes infected cats to an increased risk of secondary infections, chronic inflammatory conditions, and certain neoplastic diseases, particularly those of hematopoietic origin.

Unlike acute viral infections such as feline panleukopenia, FIV establishes chronic infection following viral integration into the host genome. Many cats may remain asymptomatic for extended periods; however, immunological dysfunction progresses insidiously and can eventually manifest as recurrent illness, poor wound healing, and increased susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens.

6.1 Transmission and Clinical Impact

FIV is transmitted primarily through horizontal transmission via bite wounds, in which infected saliva and leukocytes are inoculated into tissues. This mode of transmission explains the higher prevalence of FIV in free-roaming, intact male cats, which are more likely to engage in aggressive interactions.

Although vertical transmission from an infected queen to her kittens has been demonstrated under experimental conditions, it is considered uncommon in naturally infected populations. As a result, FIV transmission is largely behavior-driven rather than environmentally mediated, in contrast to FPV.

The clinical consequences of FIV infection stem from progressive immune dysfunction. Similar to feline leukemia virus (FeLV), FIV infection compromises both innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby increasing the likelihood of secondary bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections, as well as the development of certain lymphoid and myeloid malignancies.

6.2 Testing and Diagnosis

Because there is currently no curative therapy for FIV, identification of infected cats is a cornerstone of disease control and clinical management. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) recommends FIV testing in the following situations:

- As soon as possible after a cat is acquired

- After potential exposure to an FIV-positive cat or a cat of unknown status

- Prior to vaccination against FIV or FeLV

- Whenever a cat presents with compatible clinical illness

Importantly, FIV infection status cannot always be reliably determined based on a single test at a single time point, and repeat testing using different diagnostic modalities may be required.

6.3 Diagnostic Approaches

FIV infection is most commonly diagnosed through the detection of FIV-specific antibodies, rather than direct detection of viral nucleic acid.

Point-of-care (POC) antibody tests, such as the VETSCAN® FeLV/FIV Rapid Test and WITNESS® FeLV/FIV Rapid Test, are widely used in clinical practice. These assays detect FIV antibodies in whole blood, serum, or plasma and have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for identifying infected cats.

When a cat tests FIV antibody–positive on a Level 1 diagnostic test (POC test), confirmatory testing (Level 2 diagnostics) is recommended to rule out false-positive results. Confirmatory options include:

- FIV PCR (polymerase chain reaction)

- Western blot assay

- A POC antibody test from a different manufacturer

Conversely, if a cat tests negative for FIV antibodies but has a high risk of recent exposure, repeat testing is recommended after approximately 60 days, to allow time for seroconversion.

6.4 Vaccination Considerations and Disease Prevention

Vaccination against FIV is available in some countries; however, its use presents significant diagnostic and clinical challenges. The FIV vaccine induces antibody production that may be indistinguishable from antibodies generated by natural infection when using certain in-practice antibody detection tests. This complicates interpretation of routine screening results.

Despite this limitation, some commercially available in-practice antibody tests and validated PCR assays are capable of discriminating between vaccinated, uninfected cats and naturally infected cats, although these tests may not be universally accessible.

Due to these complexities, the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) classifies the FIV vaccine as a non-core vaccine, meaning its use should be determined based on individual risk assessment rather than routine administration. Factors influencing vaccine consideration include lifestyle, outdoor access, aggression history, and regional prevalence.

The primary and most effective method of FIV prevention remains behavioral and environmental management. Restricting unsupervised outdoor access, reducing opportunities for fighting, and implementing testing and segregation protocols are key strategies for minimizing transmission risk.

7. Comparative Summary: FPV vs FIV

Feature | Feline Panleukopenia Virus (FPV) | Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) |

Viral classification | Non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus in the family Parvoviridae, genus Protoparvovirus, species Carnivore protoparvovirus 1. Closely related to canine parvovirus (CPV-2). | Retrovirus (family Retroviridae), lentivirus subgroup. |

Nature of infection and outcome | Acute, highly contagious disease, often severe and rapidly progressive. Mortality may exceed 90% in kittens without intensive care. | Chronic, lifelong infection characterized by progressive immune dysfunction. |

Primary target cells and organs | Cells with high mitotic activity, including intestinal crypt epithelium, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues. In utero or neonatal infection may damage cerebellar or retinal cells. | Primarily targets the immune system, leading to functional immunosuppression over time. |

Primary transmission route | Fecal–oral transmission. Indirect transmission via contaminated environments and fomites (e.g., food bowls, bedding, footwear, clothing, feces, vomitus) is critical. | Predominantly via bite wounds, through saliva and infected leukocytes. Vertical transmission is uncommon in naturally infected cats. |

Environmental persistence | Extremely durable. Can survive in contaminated environments for months to years and is resistant to many routine disinfectants. | Poor environmental survival. As an enveloped virus, FIV is readily inactivated outside the host and does not persist in the environment. |

Key clinical features | Profound leukopenia (panleukopenia), fever, lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, severe dehydration, and sometimes hemorrhagic diarrhea. Complications include sepsis, shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). | Increased susceptibility to secondary infections, chronic inflammatory disease, and certain neoplasms, particularly hematologic malignancies. |

Diagnosis | Point-of-care fecal antigen ELISA tests are commonly used but have limited sensitivity. PCR testing of feces or blood is the diagnostic gold standard. | Primarily diagnosed via antibody detection using point-of-care tests. Positive results should be confirmed with PCR, Western blot, or an alternative antibody assay. |

Treatment | Supportive care only. Includes aggressive fluid therapy, antiemetics, broad-spectrum antimicrobials for secondary sepsis, nutritional support, and in some cases granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim). | No curative treatment available. Management focuses on monitoring, prevention, and treatment of secondary infections and complications. |

Prevention and vaccination | Core vaccination for all cats. Modified live virus (MLV) vaccines are commonly used but must not be administered to pregnant queens or immunocompromised cats. | Non-core vaccination (available in some countries). Vaccination decisions are based on individual risk assessment, and testing is recommended prior to vaccination. |

8. Conclusion

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) remains one of the most serious infectious threats to feline health worldwide. Despite the availability of highly effective vaccines, FPV continues to cause severe, often fatal disease, particularly in unvaccinated cats and young kittens. Reported mortality rates may exceed 90% in susceptible kittens, and even with hospitalization and intensive supportive care, survival rates typically range from 20% to 51%. The virus’s predilection for rapidly dividing cells in the bone marrow, lymphoid tissues, and intestinal crypt epithelium underlies the hallmark features of the disease, including profound leukopenia, severe gastroenteritis, systemic immunosuppression, and a high risk of septic shock and death.

Importance of Vaccination Timing and Diagnostics

Vaccination remains the cornerstone of FPV prevention, but its effectiveness is highly dependent on correct timing and population-specific risk assessment.

- Vaccination timing and maternally derived antibodies (MDAs): In kittens, the presence of maternally derived antibodies can neutralize modified live virus (MLV) vaccines, preventing active immune responses and creating a critical “immunity gap.” During this period, kittens are susceptible to infection but may fail to respond to vaccination. Because MDA levels vary widely among individuals, WSAVA and other international guidelines recommend administering multiple doses of core FPV vaccines starting at 6–8 weeks of age, repeated every 2–4 weeks, with the final dose given at 16 weeks of age or older. In high-risk settings, vaccination should continue until 20 weeks of age to ensure adequate protection.

- Diagnostic considerations: Rapid diagnosis is essential for improving outcomes, yet commonly used point-of-care (POC) antigen ELISA tests suffer from limited sensitivity, with reported values ranging from 22.9% to 55%, resulting in frequent false-negative results in clinically affected cats. However, positive POC test results, including weak positives, are highly reliable due to high specificity (often 94–100%) in symptomatic animals. Because of the risk of false negatives, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) testing of feces remains the diagnostic gold standard and should be pursued whenever clinical suspicion persists despite negative POC results.

Ongoing Relevance in Shelter and Multi-Cat Environments

FPV poses a particularly significant threat in shelter and multi-cat environments, where constant intake of susceptible animals, crowding, and environmental contamination converge.

- Environmental persistence and transmission: As a non-enveloped virus, FPV is exceptionally durable, capable of surviving on contaminated surfaces and fomites, including shoes, clothing, food bowls, and litter boxes, for months or even years. This makes indirect transmission a dominant route of infection and places even strictly indoor cats at risk.

- Shelter outbreaks and biosecurity: FPV is a leading cause of catastrophic outbreaks in shelters, often resulting in widespread morbidity, high mortality, or mass euthanasia. Effective outbreak control requires immediate and uncompromising measures, including:

- Immediate vaccination with MLV core vaccines upon intake to induce rapid protection

- Strict isolation and quarantine, with a minimum of 14 days for exposed animals and longer periods during severe outbreaks

- Thorough environmental decontamination using strongly oxidizing disinfectants, such as a 1:32 dilution of household bleach, potassium peroxymonosulfate (Virkon), or accelerated hydrogen peroxide, as many routinely used disinfectants, including quaternary ammonium compounds, are ineffective against FPV

- Impact of co-infections: FPV-associated immunosuppression markedly increases disease severity, particularly when complicated by bacterial or viral co-infections, which are common in crowded settings. Comprehensive diagnostic testing to identify concurrent pathogens is therefore essential to guide appropriate antimicrobial use and supportive care.

In summary, feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) remains a preventable yet persistently devastating disease, particularly in unvaccinated and high-density feline populations. Effective control depends on a multifaceted approach that includes timely and appropriately scheduled vaccination, accurate and early diagnosis, rigorous environmental biosecurity, and informed population-level management, especially in shelters and multi-cat environments.

Rapid point-of-care diagnostic tools, such as Bioguard’s FPV Antigen Rapid Test, play an important role in frontline clinical decision-making by enabling prompt identification of suspected cases, early isolation, and initiation of supportive care. When used in conjunction with clinical assessment, hematological findings, and confirmatory molecular diagnostics, such assays contribute meaningfully to improved outbreak control and patient management.

Continued adherence to evidence-based guidelines, combined with the strategic use of reliable diagnostic technologies and preventive vaccination programs, remains essential for reducing morbidity, mortality, and the global burden of feline panleukopenia.

References

- Parrish, C. R. (1990). Emergence, natural history, and variation of canine, mink, and feline parvoviruses. Advances in virus research, 38, 403-450.

- Verge, J., & Christoforoni, N. (1928). La gastroenterite infectieuse des chats; est-elle due à un virus filtrable. CR Seances Soc Biol Fil, 99, 312.

- REIF, J. S. (1976). Seasonally, natality and herd immunity in feline panleukopenia. American Journal of Epidemiology, 103(1), 81-87.

- Rehme, T., Hartmann, K., Truyen, U., Zablotski, Y., & Bergmann, M. (2022). Feline Panleukopenia Outbreaks and Risk Factors in Cats in Animal Shelters. Viruses, 14(6), 1248.

- Parker, J. S., Murphy, W. J., Wang, D., O’Brien, S. J., & Parrish, C. R. (2001). Canine and feline parvoviruses can use human or feline transferrin receptors to bind, enter, and infect cells.Journal of Virology, 75(8), 3896-3902.

- Parker, J. S., Murphy, W. J., Wang, D., O’Brien, S. J., & Parrish, C. R. (2001). Canine and feline parvoviruses can use human or feline transferrin receptors to bind, enter, and infect cells.Journal of Virology, 75(8), 3896-3902.

- Hueffer, K., Govindasamy, L., Agbandje-McKenna, M., & Parrish, C. R. (2003). Combinations of two capsid regions controlling canine host range determine canine transferrin receptor binding by canine and feline parvoviruses. Journal of Virology, 77(18), 10099-10105.

- Anderson, G. J., Powell, L. W., & Halliday, J. W. (1990). Transferrin receptor distribution and regulation in the rat small intestine: effect of iron stores and erythropoiesis.Gastroenterology, 98(3), 576-585.

- Chan, L. N., & Gerhardt, E. M. (1992). Transferrin receptor gene is hyperexpressed and transcriptionally regulated in differentiating erythroid cells.Journal of Biological Chemistry, 267(12), 8254-8259.

- Yến, N. T., Sơn, N. V., Ngọc, N. T., Lê Văn Hùng, N. T. G., & Hưng, P. Q. NGHIÊN CỨU MỘT SỐ BIẾN ĐỔI BỆNH LÝ VÀ ĐẶC TÍNH SINH HỌC CỦA FELINE PANLEUKOPENIA VIRUS PHÂN LẬP TRÊN MÈO Ở HÀ NỘ

- Ichijo, S. (1976). Clinical and hematological findings and myelograms on feline panleukopenia.

- Greene CE, Addie D. Feline parvovirus infection. In: Greene CE, ed.Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2006:78–86.

- Rehme, T., Hartmann, K., Truyen, U., Zablotski, Y., & Bergmann, M. (2022). Feline Panleukopenia Outbreaks and Risk Factors in Cats in Animal Shelters. Viruses, 14(6), 1248.

- Sykes, J. E. (2014). Feline panleukopenia virus infection and other viral enteritides. Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases, 187.

- Sykes, J. E. (2014). Feline panleukopenia virus infection and other viral enteritides.Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases, 187.

- Url, A., Truyen, U., Rebel-Bauder, B., Weissenböck, H., & Schmidt, P. (2003). Evidence of parvovirus replication in cerebral neurons of cats. Journal of clinical microbiology, 41(8), 3801-3805.

- Bentinck-Smith, J. (1949). Feline panleukopenia (feline infectious enteritis)-a review of 574 cases. North Am Vet, 30, 379-384.

- Jakel, V., Cussler, K., Hanschmann, K. M., Truyen, U., König, M., Kamphuis, E., & Duchow, K. (2012). Vaccination against feline panleukopenia: implications from a field study in kittens. BMC Veterinary Research, 8(1), 1-8.

- Scott, F. W., Csiza, C. K., & Gillespie, J. H. (1970). Maternally derived immunity to feline panteukopenia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 156, 439-453.

- Chappuis, G. (1998). Neonatal immunity and immunisation in early age: lessons from veterinary medicine. Vaccine, 16(14-15), 1468-1472.

- Cao, Q., Chen, Y. C., Chen, C. L., & Chiu, C. H. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: Transmission dynamics and clinical characteristics. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 119(3), 670.

- Gueguen, S., Martin, V., Bonnet, L., Saunier, D., Mähl, P., & Aubert, A. (2000). Safety and efficacy of a recombinant FeLV vaccine combined with a live feline rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleucopenia vaccine. Veterinary Record, 146(13), 380-381.

- Gore, T. C., Lakshmanan, N., Williams, J. R., Jirjis, F. F., Chester, S. T., Duncan, K. L., … & Sterner, F. J. (2006). Three-year duration of immunity in cats following vaccination against feline rhinotracheitis virus, feline calicivirus, and feline panleukopenia virus. Veterinary Therapeutics, 7(3), 213.

- Gaskell, R. M. (1989). Vaccination of the young kitten. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 30(11), 618-624.

- Truyen, U., Addie, D., Belák, S., Boucraut-Baralon, C., Egberink, H., Frymus, T. & Horzinek, M. C. (2009). Feline panleukopenia. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management.Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery,11(7), 538-546.

- Schunck, B., Kraft, W., & Truyen, U. (1995). A simple touch-down polymerase chain reaction for the detection of canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus in feces.Journal of virological methods,55(3), 427-433.

Lappin, M. R., Andrews, J., Simpson, D., & Jensen, W. A. (2002). Use of serologic tests to predict resistance to feline herpesvirus 1, feline calicivirus, and feline parvovirus infection in cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 220(1), 38-42.