Webinar: Feline Herpesvirus-1 and Related Eye Diseases

A free online class brought to you by Bioguard

Get familiar with feline herpesvirus-1 and related eye diseases. Sponsored by Bioguard Corporation and presented by Dr. Jingwen Luo, DVM / MVM/ Veterinary Ophthalmologists, this is the next webinar you don’t want to miss it.

Access to the on-demand recording is FREE

Obtain a CERTIFICATE of attendance

Wednesday

Apr 27

8 PM – 9 PM

Taipei Local Time

ABOUT THE WEBINAR

Feline herpesvirus type-1 (FHV-1) is a major cause of upper respiratory disease in cats. Young and adolescent cats are most susceptible to this common infection. FHV-1 infection, commonly referred as to as feline viral rhinotracheitis (FVR), can cause upper respiratory signs, ulcers on the cornea (keratitis), and fever.

This webinar will discuss the following:

- Epidemiology and pathogenesis of FHV-1

- Ocular manifestations caused by FHV-1

- Diagnosis of FHV-1 infection

- Treatment options

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Dr. Luo received her DVM and master degree in Clinical Veterinary Medicine from Nanjing Agricultural University in China. Currently, she is a specialist at veterinary ophthalmology and owner of Focu pet hospital, providing specialty ophthalmic services for small animals. She is also serving as the tutor for master students at Nanjing Agricultural University.

Certificate of Attendance

eCertificate will be issued to the registered attendants joining the webinar for at least 50 minutes.

How to Join: Three Options

Option 1: Watch via ZOOM

You can join us live directly via Zoom by simply registering. Please note that we will send you the link that is unique to you and should not be shared with anyone.

Option 2: Watch on our FACEBOOK Page

Follow our Facebook page and join us live during the webinar.

Option 3: Watch at your LEISURE

Registering to attend this webinar will also gain you access to the on-demand recording, which will be available 24 hours later

We look forward to seeing you at this event.

Happy Learning!

Border Collie: Breeds and their Health Issues

Photo credit: https://www.britannica.com/animal/border-collie

The classic working farm dog, the Border Collie originated in the border country between Scotland and England. Farmers bred their own individual varieties of sheepdogs for the hilly area. As Borders often tended their flock alone, they had to think independently and be able to run around 50 miles a day in hilly country. Considered highly intelligent, extremely energetic, acrobatic and athletic, they frequently compete with great success in sheepdog trials and dog sports. They are often cited as the most intelligent of all domestic dogs. Border Collies continue to be employed in their traditional work of herding livestock throughout the world and are kept as pets.

Border collies are active, working dogs best suited to country living. If confined without activity and company, these dogs can become unhappy and destructive. The breed is highly intelligent, learns quickly and responds well to praise. Border collies are extremely energetic dogs and must have the opportunity to get lots of exercise. They love to run. They also need ample attention from their owners and a job to do, whether that be herding livestock or fetching a ball.

They should be socialized well from the time they are young to prevent shyness around strangers, and they should have obedience training, which can help deter nipping behavior and a tendency to run off or chase cars.

Below we resume some important diseases more common in your Border Collie.

- Dental Disease

Dental disease is the most common chronic problem in pets affecting 80% of all dogs by age two. Unfortunately, your Border Collie is more likely than other dogs to have problems with her teeth. Dental disease starts with tartar build-up on the teeth and progresses to infection of the gums and roots of the teeth. If we don’t prevent or treat dental disease, your buddy may lose her teeth and be in danger of damaging her kidneys, liver, heart, and joints. In fact, your Border Collie’s life span may even be cut short by one to three years!

- Cancer

Cancer is a leading cause of death in older dogs. Your Collie will likely live longer than many other breeds and therefore is more prone to get cancer in his golden years. Many cancers are curable by surgical removal, and some types are treatable with chemotherapy. Early detection is critical!

- Multidrug Resistance

Multidrug resistance is a genetic defect in a gene called MDR1. If your Border Collie has this mutation, it can affect the way his body processes different drugs, including substances commonly used to treat parasites, diarrhea, and even cancer. For years, veterinarians simply avoided using ivermectin in herding breeds, but now there is a DNA test that can specifically identify dogs who are at risk for side effects from certain medications. Testing your pet early in life can prevent drug-related toxicity.

- Neurological disorders

Although the Border Collie is generally a breed noted for its vitality, they are unfortunately prone to canine epilepsy, a neurological disorder that is the result of an irregular neuroelectric activity. Signs of idiopathic epilepsy include seizures in the form of spasms, twitching, convulsions, and in extreme cases, a loss of consciousness. Idiopathic epilepsy is the most common form of the disease seen in Border Collies. A hereditary condition, IE is usually observed between 6 months and 5 years of age.

- Heart disorders

A congenital heart disease, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), is a common genetic defect that Border Collies are sadly predisposed to. PDA is a hereditary abnormality commonly observed in dogs. This heart disease typically leads to an overload of blood on the left side of the heart. In severe cases, it may lead to heart failure and death.

- Hormonal disorders

Another inherited disease that Border Collies are unfortunately subjected to include hypothyroidism, a condition that disrupts the normal production of hormones. You may observe varying signs in a dog affected by this condition, including inactivity or lethargy, weight gain, and hair loss. Once your vet has run a series of tests, if the dog has been diagnosed with this genetic defect, the dog may be placed on medication to regulate their hormonal levels.

Qmini Real-Time PCR Series:

best option for point-of-care real-time PCR application in companion animals

Real-time PCR is a powerful tool that veterinarians use to understand the cause of a wide range of diseases, including infectious disease. It is a technique used to measure the amount of specific genetic material, such as DNA or RNA, present in a sample. This technique allows veterinarians to diagnose and monitor a variety of diseases in animals and evaluate the effectiveness of treatments.

Bioguard’s Qmini Real-Time PCR Series offer exceptional sensitivity, specificity and performance for point-of-care real-time PCR application in companion animals. It can be used to detect a variety of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi. Early detection plays a key role in treating. Qmini Real-Time PCR can produces results in a few hours, making it an invaluable tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of infectious disease in animals.

Testicular Tumors

Prevalence/Incidence

- Testicular tumors are the most common tumors of the canine male genitalia and account for approximately 90% of all cancers in the male reproductive tract. In the intact male dog, the testis is the second most common anatomic site for tumor development, with an overall prevalence ranging 6-27%.

- Testicular tumors are most often diagnosed in geriatric male dogs with a median age of approximately 10 years.

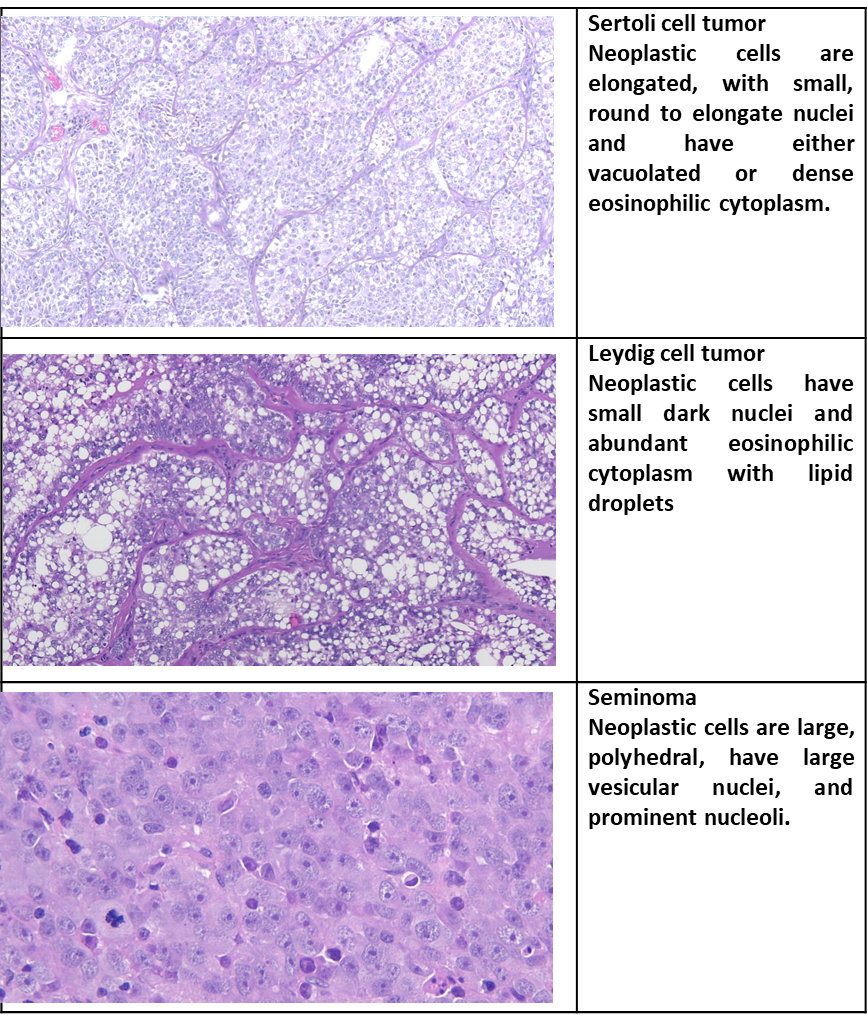

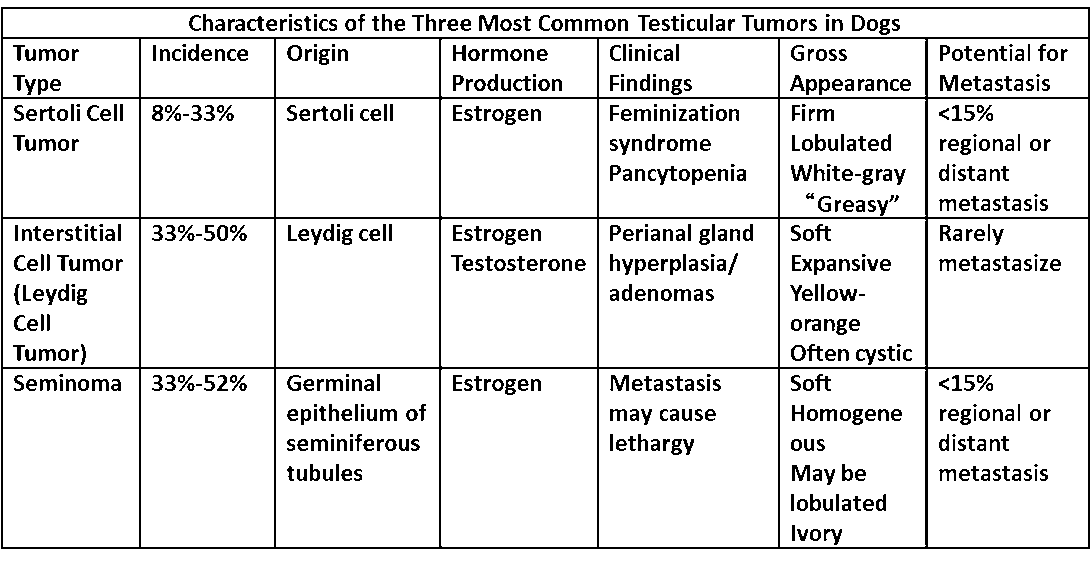

- The three most common testicular tumors arise from distinct testicular subsets: sustentacular cells of Sertoli, the spermatic germinal epithelium, and the interstitial cells of Leydig, giving rise to Sertoli cell tumors, seminomas, and interstitial cell tumors (Leydig cell tumors), respectively.

Risk Factors

Several factors may influence the development of testicular tumors in the dog, including cryptorchidism, age, breed, and carcinogen exposure. There is a significant association between cryptorchidism and the development of Sertoli cell tumors and seminomas, but not Leydig cell tumors.

Pathology

- Sertoli cell tumors arise from the sustentacular cells of seminiferous tubules and seminomas arise from the germinal epithelium of seminiferous tubules. Interstitial cell tumors arise from Leydig cells located between seminiferous tubules. All three tumors have relatively distinct appearances grossly, but require histopathology for definitive diagnosis.

- Sertoli cell tumors are firm, lobulated, white-to-gray in appearance, and often characterized as “greasy” on palpation. Seminomas tend to be homogeneous, soft, and occasionally lobulated with an ivory appearance when sectioned. Interstitial cell tumors are soft, expansive, and yellow-to-orange in color when sectioned and often contain cysts with serous or serosanguineous fluid.

Natural behavior

- Most primary testicular tumors in the dog are characterized by local invasion and rarely metastasize. Regional or distant metastasis occurs in fewer than 15% of dogs diagnosed with Sertoli cell tumors or seminomas. Interstitial cell tumors very rarely metastasize. Sites of metastasis may include regional lymph nodes (LNs), eyes, brain, lungs, kidney, spleen, liver, adrenal glands, pancreas, skin, and peritoneum.

- Primary testicular tumors can also cause imbalances in sex hormone levels. Sertoli cell tumors can cause signs of feminization and more than 50% of affected dogs display signs of estrogen overproduction. Seminomas and interstitial cell tumors are rarely associated with feminization. Excess estrogen can cause signs such as bilateral symmetric alopecia, cutaneous hyperpigmentation, epidermal thinning, squamous metaplasia of the prostatic epithelium, gynecomastia, galactorrhea, attraction of other males, preputial atrophy, atrophy of the nonneoplastic testicle, and bone marrow suppression.

History and Clinical Signs

- Most dogs with testicular tumors are asymptomatic and a testicular mass is discovered as an incidental finding. Diagnosis is usually made via palpation of an enlarged testicle or a testicular mass during routine physical examination, abdominal ultrasound, or necropsy. Atrophy of the remaining normal testicle is common. Excess estrogen may cause signs of feminization and is the most common paraneoplastic syndrome associated with canine testicular tumors.

- Common clinical signs include bilateral symmetric alopecia and hyperpigmentation, pendulous prepuce, gynecomastia, galactorrhea, atrophy of the penis, and squamous metaplasia of the prostate. The most deleterious effect of hyperestrogenism is bone marrow suppression.

Diagnosis and Staging

- Physical examination of intact male dogs, and particularly older dogs, should always include palpation of the testicles for masses and/or asymmetry. A thorough rectal examination should be performed to evaluate the prostate gland, regional LNs, and perianal region. In dogs with clinical signs of hormone imbalance (excess estrogen or testosterone), serum testosterone and estradiol-17β can be measured along with testosterone/estradiol ratio.

- Definitive diagnosis is achieved by histopathologic evaluation. Complete staging before surgery is generally recommended. Complete blood count (CBC), chemistry profile, urinalysis, abdominal ultrasound, and three-view thoracic radiographs are also recommended.

- Abdominal ultrasound can aid in identification of undescended testicles in the abdominal cavity or inguinal canal, assessment of regional LNs, assessment of prostatic changes, and evaluation of common sites of metastasis, such as the spleen and liver.

- Castration may be performed before full staging for some cases, with the decision to do full workup after histopathologic evaluation, because it is appropriate therapy for most testicular tumors. Histopathologic diagnosis is generally straightforward.

Treatment and Prognosis

- As most primary canine testicular tumors are characterized by local infiltration with low potential for metastasis, orchiectomy is the treatment of choice and is often curative. Exploratory laparotomy is indicated in cryptorchid dogs. In dogs with signs of hyperestrogenism secondary to the primary tumor, clinical signs typically resolve within 1 to 3 months after castration, unless metastatic lesions provide persistent estrogen release. Recurrence of feminization after castration may be associated with the development of metastasis.

- Dogs with bone marrow hypoplasia secondary to estrogen toxicity require close monitoring for complications requiring medical intervention with blood products and/or antibiotics. These dogs carry a guarded prognosis owing to the high morbidity and mortality associated with neutropenia and hemorrhage. Dogs with aplastic anemia likely warrant a poor prognosis.

- Primary testicular tumors occasionally metastasize to regional LNs and distant sites, and therapy other than surgery may be warranted in these dogs. Cisplatin, actinomycin-D, chlorambucil, mithramycin, and bleomycin have been used; however, too few dogs have been treated and evaluated to formulate any conclusions regarding efficacy. Cisplatin was evaluated in three dogs with aggressive testicular tumors with survival times ranging from 5 months to greater than 31 months.

Cryptorchidism

- Cryptorchidism, a common congenital genital defect in male dogs, is diagnosed if either or both testes are not present in the scrotum at puberty. Testes typically descend into the scrotum by 6 to 16 weeks of age in puppies and before birth in kittens. Late testicular descent and undescended testes are heritable defects. Testicular hormone insulin-like factor 3 is produced by prenatal and postnatal Leydig cells and mediates transabdominal testicular descent from the caudal pole of the kidney to the inguinal canal. This hormone induces growth and differentiation of the gubernaculum from the caudal suspensory ligament. Transabdominal migration of fetal testes is independent of androgen presence, but inguinoscrotal descent is mediated by testosterone. During the inguinoscrotal phase of migration, shortening of gubernaculum and eversion of cremaster muscle occur.

- Cryptorchidism is a predisposing factor for the development of Sertoli tumors and seminomas but does not appear to be a factor in the formation of interstitial cell tumors. The incidence of testicular neoplasia in the cryptorchid dogs was 12.7 per 1000 dog-years at risk, whereas for cryptorchid dogs older than 6 years the incidence increased to 68.1 per 1000 dog-years at risk. Inguinal cryptorchidism may further increase the risk of testicular tumor development compared with abdominal cryptorchidism. In one study, dogs older than 10 years were more likely to develop tumors than dogs younger than 6 years.

- Advancements in treatment include the use of laparoscopic‐assisted cryptorchidectomy. However, future studies that compare laparoscopic‐assisted cryptorchidectomy with the traditional approaches are required for a more conclusive determination of the best method for cryptorchidectomy in dogs.

- Testicular cancer is the second most common tumor in older dogs. Cryptorchid males are up to 13 times more likely to develop testicular cancer than normal dogs. Neutering is the best treatment if tumor develops, sometimes followed by chemotherapy. The only way to prevent this type of cancer from occurring is to neuter the animal as a young dog.

Distinguishing features of the principal testicular tumors