Breed-related disease: Great Dane

John K Rosembert The Great Dane, also known as the German Mastiff or Apollo of dogs, a giant breed of German origin. The Great Dane descends from hunting dogs thought to have been around for more than 400 years, and is one of the largest breeds in the world. In the middle of the 16th century, the nobility in many countries of Europe imported strong, long-legged dogs from England, which were descended from crossbreeds between English Mastiffs and Irish Wolfhounds. They were also popular with the upper class for sport, as few other dogs could bring down a wild boar. The Great Danes that were more like those we know today were developed in the 1800s. In 1880, the Germans banned the name “Great Dane” and called the breed “Deutsche Dogge,” which means German mastiff; however, the breed continues to be called Great Dane in English speaking countries. The Great Dane’s large and imposing appearance belies its friendly nature. They are known for seeking physical affection with their owners, and the breed is often referred to as a “gentle giant”. They are moderately playful, affectionate and good with children. They will guard their home. Great Danes generally get along with other animals, particularly if raised with them, but some individuals in the breed can be aggressive with dogs they do not know. There’s one unfortunate truth that Great Dane lovers must come to grips with — this giant breed doesn’t have a long lifespan. Danes don’t fully mature until about the age of 3, but while a smaller dog is middle-aged at 10, that’s very old age in the Dane. Here we gather most common disease of the Great Dane; Gastric Torsion _ Better known as bloat, gastric torsion occurs when the stomach twists, causing the abdomen to swell and stopping blood circulation. Bloat is a red-alert emergency, as the dog dies painfully within hours without surgical intervention. It’s the primary killer of Great Danes, and while other deep-chested breeds are at risk, the level of risk is highest for this breed, according to the Great Dane Club of America. Heart Disease _ Cardiomyopathy, a heart muscle disease, often plagues Danes. Likely genetic in origin, dilated cardiomyopathy cause heart enlargement. Unfortunately, the initial symptom may be the dog’s death, but if your dog develops difficulty breathing, take him to the vet. Danes are also subject to tricuspid valve disease, a congenital problem in which a heart valve doesn’t work properly. Mitral valve disease may cause the left side of the heart to fail. Hip Dysplasia _ Hip dysplasia often manifests itself in larger dog breeds and Great Danes fit the bill. Hip dysplasia is a chronic condition in which the head of the femur bone doesn’t fit into the hip socket correctly. If you adopt a Great Dane from a breeder, ask for radiographs of the parents’ hips and speak to them about the parents’ health history. Hypothyroidism _ This lack of thyroid hormone causes weakness, lethargy, hair loss and other subtle symptoms. If you feel your Dane is just not quite right but can’t put your finger on it, hypothyroidism could be the cause. Take him to the vet for testing. There’s good news for this medical problem — treatment consists of thyroid supplementation. Sources: https://pets.thenest.com/wobbler-disease-doberman-pinscher-5075.html https://www.hillspet.com/dog-care/dog-breeds/great-dane#:~:text=The%20Dane%20is%20German%20in,guardians%20of%20estates%20and%20carriages Photo Credit: https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/great-dane/

Fulminant Tritrichomonas foetus ‘feline genotype’ infection in a 3-month old kitten associated with viral co-infection

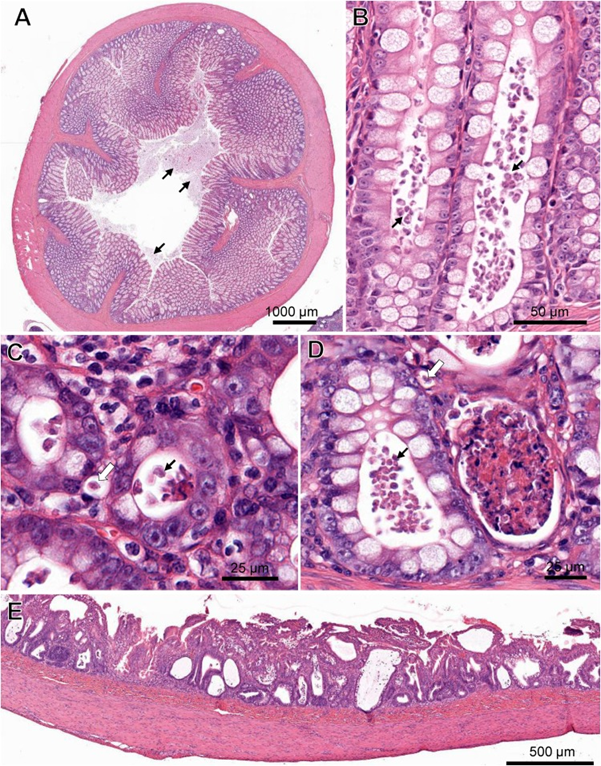

Laura Setyo, Shannon L. Donahoe, and Jan Šlapeta Original article: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.12.007 Tritrichomonas foetus is a microscopic single-celled flagellated protozoan parasite which mainly causes colitis (large bowel diarrhea) in young cats and kittens. A 3-month-old Bengal kitten showed severe T. foetus infection of the colon, cecum and ileum with concurrent feline enteric coronavirus (FCoV) and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). The kitten had an 8-day history of vomiting, diarrhoea, failure to thrive and coughing prior to being presented to the University of Sydney Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Protozoa filling the lumen and crypts and occasional invading into lamina propria were identified within the affected colon and confirmed by PCR as T. foetus‘feline genotype’. FCoV and FPV co-infection were also identified from fecal samples of the kitten via PCR. Immunosuppression caused by FPV may play a role in the unprecedented T. foetus infection intensity observed histologically. Gastrointestinal pathology in a cat co-infected with Tritrichomonas foetus, feline enteric coronavirus (FCoV) and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). (A) Cross-section of the colon with marked protozoal (T. foetus) luminal infiltrate (arrows). ( B) Numerous teardrop-shaped T. foetus overlying the mucosal luminal surface of a crypt of Lieberkühn in the colon. (C) T. foetus (arrow) in the cross-section of the crypts of the colon. (D) Crypt abscesses containing cellular and karyorrhectic debris and T. foetus (arrows) in the colon. Note the invading T. foetus in the lamina propria (arrow outlines). (E) Severe attenuation of the superficial epithelium of the small intestinal of the cat PCR positive for FCoV and FPV. H&E. (Virtual Slide for Virtual Microscopy: VM05606).

Serum Canine Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity Assay (cPLI) in Diagnosing Canine Pancreatitis

Maigan Espinili Maruquin The lipases are present from a variety of cells, including pancreatic, hepatic, and gastric cells, with similar function, ie , hydrolysis of triglycerides (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012)( Steiner JM, 2000)(Dröes and Tappin 2017). From the pancreatic origin, the canine pancreatic lipase increases in the event of pancreatic inflammation (Steiner and Williams 2003, Haworth, Hosgood et al. 2014). The canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) assay was first a radioimmunoassay, and subsequently an enzyme immunoassay, eventually developed into a commercially available specific canine pancreatic lipase assay (Steiner, Teague et al. 2003, Steiner and Williams 2003, Haworth, Hosgood et al . 2014). The serum cPLI is now used as an important specific, and sensitive marker for the exocrine pancreas (Steiner, Newman et al. 2008, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012, Mawby, Whittemore et al. 2014, Dröes and Tappin 2017). Canine Pancreatitis Disorders originating from the liver and pancreas are considered important causes of morbidity and mortality in both dogs and cats, which presents different sets of challenges in diagnosis (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Dogs have several exocrine pancreas diseases including exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), pancreatic carcinoma, and pancreatitis (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Among them, pancreatitis is the most common disorder and are mostly considered idiopathic (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). Pancreatitis is the inflammation of the exocrine pancreas, wherein there is an infiltration with inflammatory cells. The term is usually expanded to include other diseases of the exocrine pancreas by necrosis or necrotising pancreatitis, or irreversible structural changes such as fibrosis (chronic pancreatitis) (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). The pancreatitis is in acute stage when there is neutrophilic inflammation while chronic is characterized by the acinar atrophy and fibrosis (Newman, Steiner et al. 2006, Watson, Roulois et al. 2007, Mansfield, Anderson et al. 2012 , Watson 2015, Dröes and Tappin 2017). https://i2.wp.com/thewholedog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/pancreatiitis.jpg?ssl=1 Fig. 01. An illustration of the difference of healthy pancreas vs. inflamed pancreas in dogs Despite being a common disorder in canines, the antemortem diagnosis of pancreatitis is clinically challenging (Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). Clinical signs are non-specific and varies greatly. Subclinical diseases are evident in most cases while others may display mild and non -specific clinical signs (Xenoulis 2015) which may include anorexia, vomiting, lethargy, diarrhea, melena, weight loss, hematemesis, and hematochezia (Hess, Saunders et al. 1998, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). Dogs with acute pancreatitis are at risk of developing obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocortcisim, hypothyroidism, prior gastrointestinal disease, and epilepsy (Cook, Breitschwerdt et al. 1993, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011). On the other hand, cardiovascular shock,disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or multi-organ failure and death within hours of the development of clinical signs are presented in severe cases (Xenoulis 2015, Dröes and Tappin 2017). As diagnosis of pancreatitis remains a challenge, histopathology is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of pancreatitis. However, with procedural risks and difficulty to determine the right area for biopsy, obtaining the samples is hard (Newman, Steiner et al. 2004, Dröes and Tappin 2017). Therefore, considering the improving sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests, using a combination of different methods can be best used (Dröes and Tappin 2017). On the other hand, there are treatments for acute pancreatitis infected dogs. Treatments consider Intravenous Fluid Therapy, knowing that pancreatitis disturbs pancreatic microcirculation (Bassi, Kollias et al. 1994, Mansfield 2012). The administration of plasma is claimed to correct hypoalbuminemia, replacement of circulating α-macroglobulins, replacement of coagulation factors, and amelioration of systemic inflammation, however, no controlled studies on plasma transfusion in dogs with naturally occurring acute pancreatitis has proven its benefit (Mansfield 2012). Due to vomiting of infected dogs, anti-emetics are used to manage acute pancreatitis (Mansfield 2012). On the other hand, corticosteroids enhance apoptosis, and increase the production of pancreatitis-associated protein, giving protective effect against pancreatic inflammation (Zhang, Kandil et al. 2004, Mansfield 2012). Moreover, diet should also be managed including the treatment of the complications of the disease (Mansfield 2012) Canine Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity Assay Due to the limitations of the traditional golden standard, histopathology, diagnosis has relied on clinical criteria as an alternative gold standard (Graca, Messick et al. 2005, McCord, Morley et al. 2012, Cridge, MacLeod et al. 2018, Gori, Lippi et al. 2019, Nielsen, Holm et al. 2019, Okanishi, Nagata et al. 2019, Cridge, Mackin et al. 2020) and this includes measurement of cPLI (Cridge, Mackin et al. 2020). It has been proven over the decade that the PLI assay development, analytical validation, and evaluation is very useful for the diagnosis of pancreatitis in both dogs and cats (Xenoulis and Steiner 2012)( Xenoulis PG, Steiner JM, 2013). Pancreatic lipase is expressed exclusively by pancreatic acinar cells and thus plays an important role in assessing the exocrine pancreas (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Steiner, Rutz et al. 2006, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). The serum cPLI has been reported to detect specifically localized lipase in pancreatic acinar cells (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Dröes and Tappin 2017). This makes increase in serum PLI concentrations unlikely coming from the lipase of other tissues (Lidbury and Suchodolski 2016). Considering the localization of the pancreatic lipase and the capacity of immunoassays to detect the unique protein structure of pancreatic lipase are known to be the advantages of measuring the serum cPLI during the diagnosis of exocrine pancreas diseases, resulting to high analytic specificity (Steiner,Rutz et al. 2006, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012) (Steiner JM, 2000; Hoffmann WE, 2008) (Steiner, Berridge et al. 2002, Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011). Nowadays, diagnosis of canine pancreatitis has mostly considered serum cPLI assays as the most specific serum biomarkers (Neilson-Carley, Robertson et al. 2011, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Mawby, Whittemore et al. 2014). However, the serum cPLI concentration doesn’t define the severity of pancreatitis (Steiner, Newman et al. 2008, Trivedi, Marks et al. 2011, Xenoulis and Steiner 2012). References: Hoffmann WE. Diagnostic enzymology of domestic animals. In: Kaneko JJ, Harvey JW, Bruss ML, eds. Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Academic

Breed-related disease: Toyger cat

John K. Rosembert Lots of cats are named Tiger, but it wasn’t until Judy Sugden was struck by the two spots of tabby markings on the temple of her cat Millwood Sharp Shooter that it occurred to her that they could be the secret to developing a domestic cat that truly resembled the lord of the jungle. Starting with a striped domestic shorthair named Scrapmetal and a Bengal cat named Millwood Rumpled Spotskin, and later importing a street cat from Kashmir, India, who had spots instead of tabby lines between his ears, she went to work to create a tiger for the living room. Other breeders who shared her vision and contributed to the breeding program were Anthony Hutcherson and Alice McKee. They came up with a domestic cat that had a large, long body, tabby patterns and rosettes that stretched and branched out, and circular head markings. The International Cat Association began registering the Toyger in 1993, advanced it to new breed status in 2000, and granted the breed full championship recognition in 2007. Currently, TICA is the only association that recognizes the Toyger. oygers are instantly recognisable by their beautiful coat patterns. Their coats are dense and luxuriously soft, with a modified mackerel tabby pattern with branching and interweaving stripes. Brown mackerel tabby is currently the only recognised colour, giving these cats a black and gold striped look, much like a miniature tiger. The Toyger has a sleek, muscular body with a long, thick tail, which is carried low as well as small, rounded ears, and small to medium eyes, which are normally yellow or green. The friendly and playful Toyger likes people and other pets. He delights in playing fetch, batting around a feather or fishing-pole toy, and just spending time with family members. He’s active enough to learn tricks, but not so energetic that he’ll run you ragged. He has an easygoing personality that makes him suited to most households or families. The Toyger is generally a healthy cat and is no more predisposed to infectious diseases than any other breed. Some breeders claim that some cats show an adverse reaction to the feline leukaemia vaccine, but this has not been substantiated. Responsible breeders screen their cats against diseases to which Bengals can be prone, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), pyruvate kinase deficiency (PKDef), and progressive retinal atrophy (PRA). However, anecdotal reports indicate that the incidence of all these conditions is significantly lower than in the Bengal, due to the Toyger’s outcross to domestic shorthairs. As they have dense, short hair, Toygers’ coats are very low maintenance, and only need to be brushed once a week. Sources: https://www.yourcat.co.uk/types-of-cats/toyger-cat-breed-information/ http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/toyger#health Photo credit : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyger