Breed-related disease: Border Collie

The classic working farm dog, the Border Collie originated in the border country between Scotland and England. Farmers bred their own individual varieties of sheepdogs for the hilly area. As Borders often tended their flock alone, they had to think independently and be able to run around 50 miles a day in hilly country. Considered highly intelligent, extremely energetic, acrobatic and athletic, they frequently compete with great success in sheepdog trials and dog sports. They are often cited as the most intelligent of all domestic dogs. Border Collies continue to be employed in their traditional work of herding livestock throughout the world and are kept as pets. Border collies are active, working dogs best suited to country living. If confined without activity and company, these dogs can become unhappy and destructive. The breed is highly intelligent, learns quickly and responds well to praise. Border collies are extremely energetic dogs and must have the opportunity to get lots of exercise. They love to run. They also need ample attention from their owners and a job to do, whether that be herding livestock or fetching a ball. They should be socialized well from the time they are young to prevent shyness around strangers, and they should have obedience training, which can help deter nipping behavior and a tendency to run off or chase cars. Below we resume some important diseases more common in your Border Collie. Dental Disease Dental disease is the most common chronic problem in pets affecting 80% of all dogs by age two. Unfortunately, your Border Collie is more likely than other dogs to have problems with her teeth. Dental disease starts with tartar build-up on the teeth and progresses to infection of the gums and roots of the teeth. If we don’t prevent or treat dental disease, your buddy may lose her teeth and be in danger of damaging her kidneys, liver, heart, and joints. In fact, your Border Collie’s life span may even be cut short by one to three years! Cancer Cancer is a leading cause of death in older dogs. Your Collie will likely live longer than many other breeds and therefore is more prone to get cancer in his golden years. Many cancers are curable by surgical removal, and some types are treatable with chemotherapy. Early detection is critical! Multidrug Resistance Multidrug resistance is a genetic defect in a gene called MDR1. If your Border Collie has this mutation, it can affect the way his body processes different drugs, including substances commonly used to treat parasites, diarrhea, and even cancer. For years, veterinarians simply avoided using ivermectin in herding breeds, but now there is a DNA test that can specifically identify dogs who are at risk for side effects from certain medications. Testing your pet early in life can prevent drug-related toxicity. Neurological disorders Although the Border Collie is generally a breed noted for its vitality, they are unfortunately prone to canine epilepsy, a neurological disorder that is the result of an irregular neuroelectric activity. Signs of idiopathic epilepsy include seizures in the form of spasms, twitching, convulsions, and in extreme cases, a loss of consciousness. Idiopathic epilepsy is the most common form of the disease seen in Border Collies. A hereditary condition, IE is usually observed between 6 months and 5 years of age. Heart disorders A congenital heart disease is a common genetic defect that Border Collies are sadly predisposed to, Patent Ductus Arteriosus(POA) is a hereditary abnormality commonly observed in dogs. This heart disease typically leads to an overload of blood on the left side of the heart. In severe cases, it may lead to heart failure and death. Hormonal disorders Another inherited disease that Border Collies are unfortunately subjected to include hypothyroidism, a condition that disrupts the normal production of hormones. You may observe varying signs in a dog affected by this condition, including inactivity or lethargy, weight gain, and hair loss. Once your vet has run a series of tests, if the dog has been diagnosed with this genetic defect, the dog may be placed on medication to regulate their hormonal levels. Sources: http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/border-collie#health https://www.pet-medcenter.com/storage/app/media/PDF/Dog_pdf/border-collie.pdf Photo Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Border_Collie#/media/File:BORDER_COLLIE,_Simaro_Million_Dollar_Baby_(24290879465)_2.jpg

Leptospirosis and immune-mediated hemolytic anemia: A lethal association

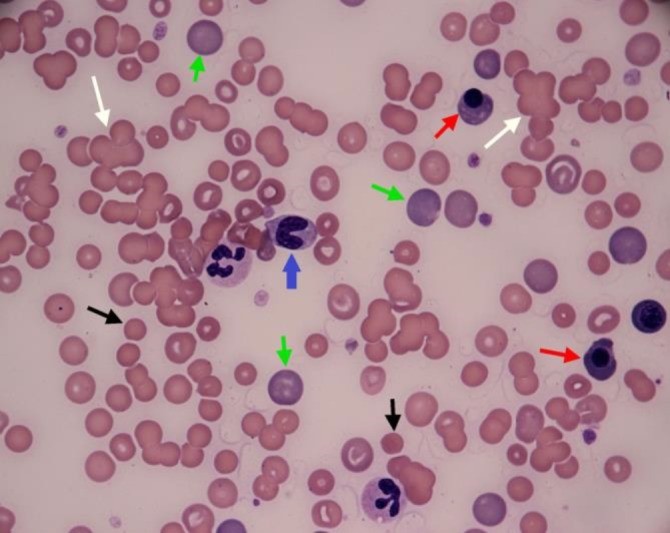

Tommaso Furlanello* and Ida Reale Vet Res Forum. 2019 Summer; 10(3): 261–265. Published online 2019 Sep 15. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2019.99876.2385 An eight-year old crossbreed dog was referred to San Marco Veterinary Clinic with a history of acute illness presenting a severe hemolytic anemia, and intense icterus most likely immune-mediated condition. Circulating antibodies against red blood cells were detected via flow cytometry, while vector-borne diseases were ruled out because of negative results of serological tests for the most common vector-borne diseases in this case. However, leptospirosis was excluded. This resulted in an unsuccessful immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone, two whole blood transfusions and ultimately death of the patient. Leptospirosis was confirmed by both micro-agglutination test for antibodies and PCR test of urine sample. Fig. 1 Blood Smear of the examined dog. White arrows: agglutinates, green arrows: large polycromatophils RBCs, black arrows: spherocytes; red arrow: nucleated RBC, blue arrow: band granulocyte neutrophil. The two-segmented neutrophils visible in the picture display foamy and basophilic cytoplasm, as signs of toxicity, (Diff Quik stain; 100×).

The Importance of AGP in FIP Diagnosis: An Overview

Maigan Espinili Maruquin The Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) The coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses with non-segmented genomes of around 30,000 nucleotides in length (Tasker 2018)( Siddell SG, 1995). The feline coronavirus (FCoV) has two pathotypes distinguished by their biological behavior. The highly prevalent feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) is highly contagious with transmission from faeces of shedding cats (Felten and Hartmann 2019). However, most cases are asymptomatic or displays mild gastrointestinal clinical signs, (Addie, Toth et al. 1995, Pedersen, Sato et al. 2004, Pedersen, Allen et al. 2008, Pedersen 2009, Vogel, Van der Lubben et al. 2010, Tasker 2018, Felten and Hartmann 2019). On the other hand, the feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) is a mutation within a small percentage of infected cats and it results to a fatal disease feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), commonly in young cats (Pedersen, Boyle et al. 1981, Pedersen, Boyle et al. 1981, Addie, Toth et al. 1995, Vennema, Poland et al. 1998, Pedersen 2009, Tasker 2018, Felten and Hartmann 2019). However, the exact gene causing mutation is still unknown (Felten and Hartmann 2019). The FIP may appear in two clinically distinct forms: the wet form and dry form, which is effusive and granulomatous forms, respectively (Wolfe and Griesemer 1966, Montali and Strandberg 1972, Pedersen 2009, Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016). The development of FIP is affected by three factors. First is the viral factor wherein studies relative to mutation of the FCoV S gene where presented (Tasker 2018) and the replication in monocytes, and activation of infected monocytes were also considered important in the development of FIP (Kipar and Meli 2014, Tasker 2018). Second factor considered is the host’s immune response, breed and genetic (de Groot-Mijnes, van Dun et al. 2005, Dewerchin, Cornelissen et al. 2005, Golovko, Lyons et al. 2013, Pedersen, Liu et al. 2016, Tasker 2018). Finally, another factor affecting the FIP development is the environment- level of stress and overcrowding (Tasker 2018). https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cat-with-wet-effusive-form-of-FIP-presenting-moderate-abdominal-distention-due-to_fig7_51758582 Fig. 01. Manifestation of moderate abdominal distention due to peritoneal effusion. A clinical sign of wet (effusive) FIP. Common clinical signs for the FIP infected cats include lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, fluctuating pyrexia, and sometimes presents jaundice (Tasker 2018). On the other hand, wet FIP cases can be associated with abdominal, pleural and/ or pericardial effusions, and progresses within few days to weeks with severe limiting survival (Ritz, Egberink et al. 2007, Tasker 2018). Whereas, dry FIP usually displays neurological signs (Crawford, Stoll et al. 2017) or ocular signs, which progresses in a few weeks to months and are more chronic (Tasker 2018). The alpha- 1 acid glycoprotein (AGP) in FIP diagnosis Prior to acquired immune response, part of the innate response is the acute phase response (Murata, Shimada et al. 2004, Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). Proteins known as the acute phase proteins (APPs) are then increased in production from hepatocytes and peripheral tissues and then released (Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). These blood proteins can be used to evaluate the innate response to infection, inflammation or trauma (Murata, Shimada et al. 2004, Petersen, Nielsen et al. 2004, Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Eckersall and Bell 2010). With changes by >25% in the serum concentration in response to disease stimulation, APPs are considered useful quantitative biomarkers of diseases- in diagnosis, prognosis, response to therapy, and in general health screening (Eckersall and Bell 2010). In response to inflammations, the serum alpha- 1 acid glycoprotein (AGP) concentration increases as a major acute phase protein in cats (Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Paltrinieri 2008, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011). Studies showed increased serum AGP concentration in cats infected with FIP (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Giordano, Spagnolo et al. 2004, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011). The feline AGP in both serum and peritoneal fluid are known biomarker for FIP (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Giordano, Spagnolo et al. 2004, Eckersall and Bell 2010). In a study conducted, AGP in effusion showed to be the best APP to distinguish between cats with and without FIP (Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016). Although AGP elevations are not specific for FIP, the measurement is helpful in the diagnosis of FIP, and levels >1.5 mg/ml are often observed in FIP cases (Tasker 2018). It was then concluded that the higher levels increase the index of suspicion (Duthie, Eckersall et al. 1997, Paltrinieri, Giordano et al. 2007, Giori, Giordano et al. 2011, Hazuchova, Held et al. 2016, Tasker 2018). With difficulty in diagnosing FIP through conventional approaches (Addie, Paltrinieri et al. 2004, Paltrinieri 2008), samples from FIP infected cats showed AGP seemed to be associated with viral antigen and are seen present in large amounts (Paltrinieri, Giordano et al. 2004, Paltrinieri 2008). Nevertheless, AGP plays role in drug-binding, as an immunomodulatory agent, and acts as a plasma transport protein (Ceron, Eckersall et al. 2005, Ceciliani, Ceron et al. 2012, Schmidt and Eckersall 2015). References: Siddell SG. The coronaviridae. London: Plenum Press, 1995 Drechsler, Y., Alcaraz, A., Bossong, F., Collisson, E.W., Diniz, P. (2011), “Feline Coronavirus in Multicat Environments”. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 41(6):1133-69. Addie, D. D., S. Paltrinieri, N. C. Pedersen and s. Secong international feline coronavirus/feline infectious peritonitis (2004). “Recommendations from workshops of the second international feline coronavirus/feline infectious peritonitis symposium.” Journal of feline medicine and surgery 6(2): 125-130. Addie, D. D., S. Toth, G. D. Murray and O. Jarrett (1995). “Risk of feline infectious peritonitis in cats naturally infected with feline coronavirus.” Am J Vet Res 56(4): 429-434. Ceciliani, F., J. J. Ceron, P. D. Eckersall and H. Sauerwein (2012). “Acute phase proteins in ruminants.” J Proteomics 75(14): 4207-4231. Ceron, J. J., P. D. Eckersall and S. Martýnez-Subiela (2005). “Acute phase proteins in dogs and cats: current knowledge and future perspectives.” Vet Clin Pathol 34(2): 85-99. Crawford, A. H., A. L. Stoll, D. Sanchez-Masian, A. Shea, J. Michaels, A. R. Fraser and E. Beltran (2017). “Clinicopathologic Features and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in 24 Cats With Histopathologically Confirmed Neurologic Feline Infectious Peritonitis.” J Vet Intern Med 31(5): 1477-1486.