Pneumonia and gastritis in a cat caused by feline herpesvirus-1

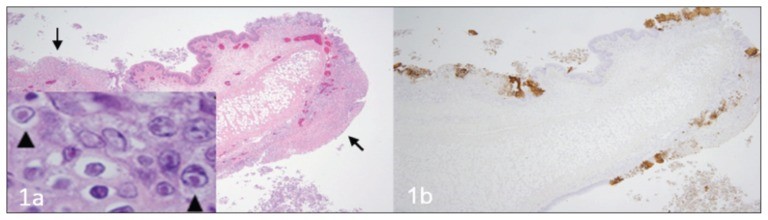

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712990/ A fatal respiratory and gastric herpesvirus infection in a vaccinated, 6-year-old neutered male domestic shorthair cat with no known immunosuppression or debilitation. Histology examination revealed severe necrotizing bronchopneumonia, fibrinonecrotic laryngotracheitis, and multifocal necrotizing gastritis associated with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies in affected tissues of larynx, trachea, lung and stomach. Immunohistochemistry also displayed strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in the corresponding section of larynx, trachea, lung and stomach. Figure 1 Larynx. Cat. a — Note the multifocal areas of ulceration (arrows) and inflammation. Inset: inclusion bodies (arrowheads) within epithelial cells adjacent to areas of ulceration. H&E. b — Immunohistochemistry of the corresponding section of larynx displaying strong multifocal immunoreactivity for FHV-1. Figure 2 Trachea. Cat. a — Note the denuded tracheal mucosa covered by a thick fibrinonecrotic exudate (asterisks), attenuation of the epithelium lining the tracheal glands (arrows) and numerous inflammatory cells infiltrating the tracheal wall. Inset: Inclusion bodies within the epithelial cells lining the tracheal glands (arrowheads). H&E. b — Strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in the epithelium of the trachea and tracheal glands. Figure 3 Lung. Cat. a — Severe neutrophilic necrotizing bronchopneumonia affecting airways (asterisks) and surrounding tissues. H&E. b — Strong immunoreactivity for FHV-1 in bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. Figure 4 Stomach. Cat. a — Area of necrosis within the gastric mucosa (asterisk). H&E. b — Multifocal areas of FHV-1 immunoreactivity corresponding to areas of necrosis within the gastric mucosa.

Feline Tritrichomonas Foetus Infection: A Review

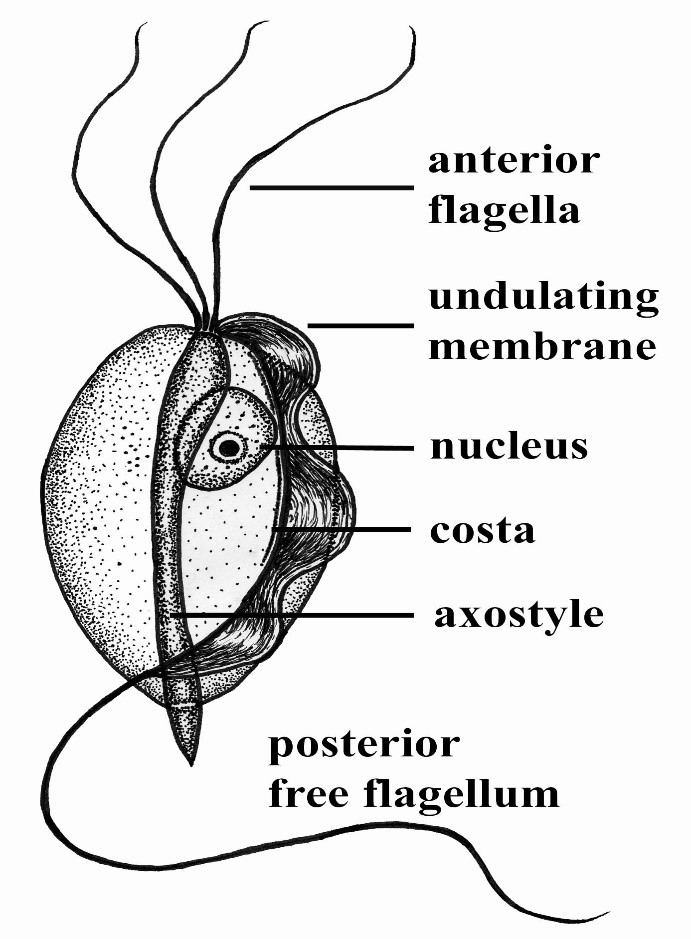

Maigan Espinili Maruquin Structure and Epidemiology The protozoan parasite Tritrichomonas foetus has sudden emergence of its syndrome in the 1990s causing feline intestinal tritrichomoniasis and has then attracted feline medicine studies (Levy, Gookin et al. 2003, Bell, Gowan et al. 2010) (Levy, Gookin et al. 2001 ). At a range of 10- 31%, infected cats in UK and USA comes from young, pedigree cats in multi-cat environment (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Gookin, Stebbins et al . 2004, Gunn-Moore, McCann et al. 2007, Frey, Schild et al. 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009)( Gunn-Moore D, Tennant B, 2007)(Bell, Gowan et al. 2010). An estimate 30% of purebred cats in USA are suggested infected by T. foetus (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Gookin, Stauffer et al. 2010). The T. foetus , like other trichomonads, has only trophozoite stage, however, it has a pseudocyst stage (Lipman NS, et. al., 1999) (Pereira-Neves, Ribeiro et al. 2003, Benchimol 2004, Mariante, Lopes et al. 2004, Yao and Köster 2015). Therefore, cats are presumed to be infected via direct contact due to the absence of the cyst stage (Zajac AM, Conboy GA, 2006). The parasite is pear- or spindle-shaped, having three anterior flagella and one posterior flagellum. With its size of approximately 10-25 μm in length and 3-15 μm in width, the undulating membrane extends along the whole length of the body which emerges as the posterior flagellum. This trophozoite reproduces asexually by longitudinal binary fission (Yao and Köster 2015). (https://www.k-state.edu/parasitology/625tutorials/Protozoa10.html) Fig. 01. Morphologic structure of the Tritrichomonas foetus Infected cats were reported to experience chronic large bowel diarrhea as the parasite was found in the feline intestine (Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Payne and Artzer 2009). Reports also showed the presence of the organism in the feline uterus (Dahlgren, Gjerde et al. 2007). Further, the isolates of T. foetus from cattle are known to be infectious for the cats, while the isolates of the same species from cats are infectious to cattle (Stockdale, Dillon et al. 2008, Walden, Rodning et al. 2008, Payne and Artzer 2009). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis Despite suggestions of strong association of feline T. foetus and chronic diarrhea (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Mardell and Sparkes 2006, Gunn-Moore, McCann et al. 2007, Burgener, Frey et al. 2009, Holliday, Deni et al. 2009, Pham 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009, Kuehner, Marks et al. 2011), whether the parasite alone is sufficient to cause clinical signs or the foetus-associated diarrhea, being a primarily multifactorial disease involves concurrent infection with other enteropathogens, host and environmental factors (Gookin, JL, et. al., 1999) (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Bissett, Gowan et al. 2008, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009, Kuehner, Marks et al. 2011). It is possible that the trophozoites are transmitted by a fecal- oral route from an infected to uninfected cat (Yao and Köster 2015). Symptoms may appear early as 2 to 7 days after orogastric inoculation (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015). Whereas, infected cats showed anorexia, depression, vomiting and weight loss while experimental infections also reported vomiting and fever (Mardell and Sparkes 2006, Xenoulis, Lopinski et al. 2013, Yao and Köster 2015)( Stockdale, H., et al., 2007). Chronic large bowel diarrhea, associated with blood, mucus, flatulence, tenesmus, and anal irritation were also reported (Foster, Gookin et al. 2004, Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Payne and Artzer 2009, Stockdale, Givens et al. 2009). With the characteristic of the trichomonads as commensal organisms, some hosts show no clinical signs and are asymptomatic (Payne and Artzer 2009). In some studies, the parasite, with its surface located antigen, was detected on epithelial surface and within the superficial detritus of the cecal and colonic mucosa (Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015), while naturally infected cats showed parasite in close proximity to the mucosal surface and less frequently in the lumen of colonic crypts (Yaeger and Gookin 2005, Yao and Köster 2015). Conclusively, T. foetus trophozoites can be detected in epithelial surface and crypts of cecum and colon (Yao and Köster 2015). Mechanisms were then described to include possibilities of alterations in the normal intestinal flora, adherence to the epithelium, and elaboration of cytokines and enzymes (Payne and Artzer 2009). Diagnosis For cats <6months old with recent clinical signs of chronic large bowel diarrhea, infection with T. foetus infection is suspected (Yao and Köster 2015). Diagnosis of the T. foetus infection may be conducted via direct observation of the flagellates in fresh or cultured feces (Payne and Artzer 2009) or on a saline diluted direct fecal smear (Yao and Köster 2015). The trophozoites of T. foetus are difficult to distinguish from Giardia spp and other nonpathogenic intestinal trichomonads. However, although the size of T. foetus and Giardia spp are almost the same, they move differently. The movement of Giardia spp. resembles the fall of a leaf while trichomonads move erratically (Yao and Köster 2015)( Gookin JL, Levy MG, 2008). Feline feces can be cultivated and be tested in commercially available InPouch™ TF medium (Payne and Artzer 2009, Yao and Köster 2015) or DNA extraction and amplification of T. foetus rDNA by the use of PCR from feces samples can be conducted (Gookin, Stebbins et al. 2004, Manning 2010, Yao and Köster 2015). Moreover, other causes of diarrhea, like bacterial, viral, other parasites, and nutritional problems should be ruled out before a diagnosis of tritrichomoniasis can be made (Payne and Artzer 2009). Treatment and Disease Managements The T. foetus infection in cats has no approved treatment. While treating infected animals is difficult, success is also limited (Payne and Artzer 2009). Literatures have used therapeutics including paromomycin, fenbendazole, furazolidone, nitazoxanide, metronidazole, tinidazole and ronidazole (Gookin, Breitschwerdt et al. 1999, Gookin, Levy et al. 2001, Yao and Köster 2015). The ronidazole is not registered for human or veterinary use (Yao and Köster 2015) however, it showed effectiveness in experimentally infected cats (Gookin, Copple et al. 2006) (Gookin JL, Dybas D, 2008). Due to possible neurologic side effects, caution is observed

Leptospirosis

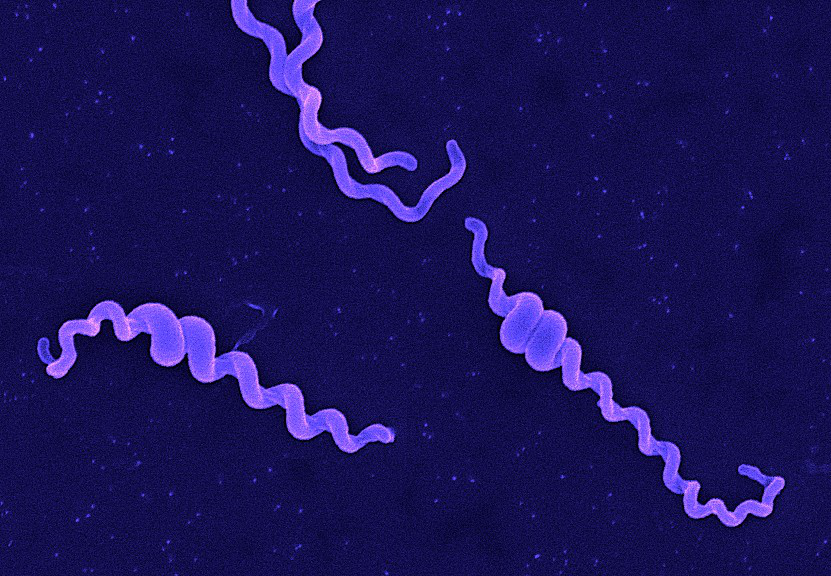

Andy Hua Introduction Classification Taxonomy Classically, the genus Leptospira was divided into 2 species based on genetic analysis: L. interrogans sensu latu (pathogenic strains) and L. biflexa sensu latu (saprophytic strains). L. interrogans is divided into more than 250 serovars based on antigenic composition and further classified into antigenically related serogroups. There is a serovar spectrum and frequency that differs according to countries and regions (depending on distribution of rodent hosts, import of dogs from abroad, use of vaccination). The main infecting serovars in dogs were Icterohaemorrhagiae and Canicola in Europe and America prior to 1960. Since the use of the bivalent vaccine against Canicola and icterohaemorrhagiae , OTHER serovars A to the Shift occurred .Besides. L. icterohaemorrhagiae and L. canicola , serovars Importance of Dogs in the include: grippotyphosa , Bratislava , Saxkoebing , Sejroe , Copenhagi , Australis , Bataviae , and Pomona , autumnalis , and hardjo . Icterohaemorrhagiae and Canicola infections in unvaccinated dogs still occur, indicating that these serovars are not fully eradicated. Leptospires are motile, obligate aerobe, gram-negative bacteria, which are not visible in routinely fixed smears. Dark field microscopy (Fig. 1) or phase contrast microscopy is necessary for visibility of unstained leptospires. Clinical Effects Epidemiology Habitat Leptospires have been isolated from birds, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates. Rodents and wild carnivores are the most frequent carriers. Reservoir hosts show few or no signs of disease. Leptospira spp. are commonly sequestered in the renal tubules of mammalian kidneys. Different serovars typically have different reservoir hosts. Lifecycle Generation time in culture media or host is long. Transmission Direct or indirect transmissions are possible. Indirect transmission through contaminated water or soil is more common. Pathological effects Infection occurs through ingestion of infected rodents or penetration of mucosae or traumatized skin. Leptospiremia occurs within 1 week. Leptospires spread to other organ systems (kidneys, liver, spleen, endothelial cells, lungs, uvea/retina, skeletal and heart muscles, pancreas, and genital tract) and cause tissue damage, visceral and vascular inflammation. Leptospiral pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome (LPHS) Lung: pulmonary hemorrhage can occur as severe manifestation of acute leptospirosis. Leptospires can persist in immune privileged site (eg, renal tubes, eye). In the presence of adequate antibody titers, leptospires are eliminated from most organs. In the presence of low antibody titers mild leptospiremia can continue with a subclinical course of disease. Other Host Effects Individual host may show little or no clinical signs but may be source of infection in the same animal species. An animal that has recovered may become a long-term shedder of the organism. Mainly dogs show disease, rodents often the reservoir. Cat disease is uncommon, but serology shows that asymptomatic infection occurs. Individual host can show little or no clinical signs but can be source of infection to other animals or humans. An animal that has recovered can become a long-term shedder of the organism. Rodents are often the reservoir. Dogs commonly succumb to disease if infected. In cats, disease is uncommon but asymptomatic infection and shedding in urine occurs. Control Control via animal Antimicrobial therapy Dogs with gastrointestinal signs should initially be treated with intravenous penicillin derivates (eg, ampicillin or amoxicillin 20-30 mg/kg q6-8h). These should be continued until gastrointestinal signs are under control and liver enzymes are normalized. A directly following antimicrobial therapy with 3 weeks of oral doxycycline (5 mg/kg q12h) is necessary for prevention of carrier states. Dogs without gastrointestinal signs should immediately be treated with doxycycline. Antibody testing of dogs living in the same household as infected dogs is recommended. Oral doxycycline (5 mg/kg q12h for 3 weeks) should be administered, if these dogs have antibodies. Symptomatic treatment Treatment of dogs with gastrointestinal sings includes antiemetics, gastroprotectants, and nutritional support. Use of opioids in dogs with pain can be necessary. Treatment of dogs with acute kidney injury (AKI) includes correction of loss of fluid, electrolytes, acid-base imbalances and hypertension, and if necessary hemodialysis for patients with persistent oligoanuria, life-threatening hyperkalemia, or severe volume overload. Oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation can be necessary in dogs with LPHS. Plasma transfusions can be necessary for patients with DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation). Whole blood transfusion can be helpful, if bleeding occurs. Hemodialysis Hemodialysis is necessary in dogs with acute renal failure (life-threatening hyperkalemia or severe volume overload) and in dogs with advanced uremia refractory to medical management. Early referral to facilities where hemodialysis is available is recommended. Renal recovery usually occurs after 2-7 days of dialytic support. Hemodialysis leads to favourable prognosis for renal recovery (in more than 80% of dogs). Mechanical ventilation Anesthesia ventilators: overview can be necessary in dogs with severe pulmonary hemorrhage due to LPHS. Vaccination Vaccination protects against clinical disease and carrier status with shedding. Protection is serogroup-specific and temporary. Annual boosters are required. Diagnosis Leptospirosis at its onset is often misdiagnosed as aseptic meningitis, influenza, hepatic disease or fever (pyrexia) of unknown origin. Despite being common, the diagnosis of leptospirosis is often not made unless a patient presents with textbook manifestations of the so called Weil’s disease, such as fever plus jaundice, renal failure and pulmonary haemorrhage. Leptospiral infection often has minimal or no clinical manifestations; of the cases in which fever develops, as many as 90% are undifferentiated febrile illnesses. Moreover, clinicians may fail to recognize that transmission of leptospirosis can occur in the urban setting because it is incorrectly perceived to be a rural disease. Therefore, diagnosis is based on laboratory tests rather than on clinical symptoms alone. In developing countries,Laboratory facilities may be inadequate for diagnosis a high prevalence of the disease. Of substantial clinical importance despite the syndrome of leptospiral pulmonary haemorrhage has emerged in recent years, in diverse places around the world. Two important issues continue to confront clinicians regarding leptospirosis. The first is how to reliably establish the diagnosis. The most common way to diagnose leptospirosis is through serological tests either the Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT) which detects serovar-specific antibodies, or a solid- phase assay for the detection of Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. Leptospira are present in the blood until they are

Breed-related disease: Cymric cat

Is it really a cat if it doesn’t have a tail? It is if it’s a Cymric (pronounced kim-rick). There are lots of cats with short tails or no tails, but the Cymric (and his sister breed the shorthaired Manx) is the only one specifically bred to be tail-free. Sometimes jokingly said to be the offspring of a cat and a rabbit (however cute the idea, a “cabbit” is biologically impossible), these particular tailless cats are the result of a natural genetic mutation that was then intensified by their remote location on the Isle of Man, off the coast of Britain. The cats are thought to date to 1750 or later, but whether a tailless cat was born there or arrived on a ship and then spread its genes throughout the island cat population is unknown. The island became known for tailless cats, and that is how the breed got its name of Manx. The Manx has long been recognized by the Cat Fanciers Association, The International Cat Association, and other cat registries. A longhaired version was accepted by CFA as a division of the Manx in 1994. In some associations, the longhaired Manx is called a Cymric and is considered a separate breed. The overall appearance should be that of a medium-sized, compact, muscular cat. The Cymric has a round head with a firm muzzle and prominent cheeks, short front legs, height of hindquarters, great depth of flank, and a short back, which forms a smooth continuous arch from the shoulders to the round rump. The Manx and Cymric are essentially the same in all respects, the Cymric having a longer coat. The Cymric has a medium/semi-long coat with a silky texture, which varies with coat color. Britches, tufts of hair between the toes and full furnishings in the ears distinguish the Cymric. The personality of the Cymric has won a strong following. Cymrics are intelligent, fun-loving cats, and they get along well with other pets, including dogs. Cymrics are particularly noted for their loyalty to their humans and enjoy spending quality time with them. As cats go, they can be easily taught tricks. Despite their playful temperament, they are gentle and nonaggressive. Here below, we listed some of the most common diseases to look for in your Cymric: Congenital Vertebral Malformations Sacrocaudal dysgenesis is a form of spinal deformity commonly seen in Cymric kittens. The sacrum is the part of the spine that passes through the pelvis, caudal means “towards the tail”, and dysgenesis means improper formation during fetal development. Sacrocaudal dysgenesis, then, means that the tail end of the spine forms improperly during fetal development—a common problem when a cat’s tail is genetically programmed to be missing. Affected kittens whose spine and spinal nerves aren’t functioning correctly may have fecal or urinary incontinence, or may walk with a hopping, abnormal gait. Constipation and megacolon are also more common in affected cats, and the effects of the condition typically worsen with age. Megacolon Megacolon is a serious and chronic form of constipation caused by a defect in the nerve supply to the intestines. Cats with megacolon have an insufficient number of nerves linked to the muscles of the colon and are unable to pass stool properly. As the cat gets older, the condition worsens, causing an increase in discomfort and blockage. Each time the cat is constipated, the intestines are stretched, bruised, and further damaged. This damage leads to larger and harder stools and, eventually, complete blockage. Megacolon is a life-threatening condition, but early and aggressive treatment can delay or prevent the necessity of major surgery to remove the colon. FLUTD When your cat urinates outside the litter box, you may be annoyed or furious, especially if your best pair of shoes was the location chosen for the act. But don’t get mad too quickly—in the majority of cases, cats who urinate around the house are sending signals for help. Although true urinary incontinence, the inability to control the bladder muscles, is rare in cats and is usually due to improper nerve function from a spinal defect, most of the time, a cat that is urinating in “naughty” locations is having a problem and is trying to get you to notice. What was once considered to be one urinary syndrome has turned out to be several over years of research, but current terminology gathers these different diseases together under the label of Feline Lower Urinary Tract Diseases, or FLUTD. Sources: https://ahcfargo.com/client-resources/breed-info/cymric-longhaired-manx-2/ https://cattime.com/cat-breeds/cymric-cats#/slide/1 Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cymric_cat https://www.petfinder.com/cat-breeds/cymric/

Breed-related disease: Maltese dog

John K. Rosembert The Maltese is an ancient breed, one of several small “bichon” dogs found around the Mediterranean for thousands of years. His exact place of origin is a mystery, with conjecture including Sicily, Egypt, and southern Europe, but most historians pinpoint Malta for the development of the breed. With its teeny-tiny stature, flowing white coat, and high trainability, this toy breed has beauty and brains. For that, it’s been cherished since its earliest days in ancient Italy and has long been seen as a portable and charming companion. The Maltese puppy truly is the quintessential lap dog, with its fluffy white fur, adorable black-button nose, dark eyes, and sprightly demeanor. “They’re like a little stuffed animal,” Derse says. The Maltese has a compact, athletic body, small floppy ears, and a tufted tail that curves over her back. By the time a Maltese reaches her full 7–9 inch height and 4–6 pound weight, those white tresses become silky smooth, requiring daily brushing along with regular baths to maintain their regal appearance. If you’re looking for a friendly dog with elegance and charm, look no further than the Maltese! With their silky, pure white coats and warm temperaments, it’s no surprise that they’ve made popular companions for people for centuries. People fall head over heels for this breed because of its adorable look, but their loyal personality makes them a fantastic option for anyone that’s looking for a canine friend. You will find no lack of adorableness, loyalty, or intelligence in this famous toy dog breed. Like other toy breeds, Maltese are prone to certain health issues. However, some of these conditions can be prevented if you keep up with routine care and checkups, here below we listed some of the most common illnesses run in their genes… Let’s get started: Inflammatory Bowel Disease Other common health conditions Maltese face affect their intestines. The breed can also develop severe food allergies and sensitivities. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or IBD for short, occurs when your dog’s intestines become overactive with lymphocytes and plasmacytes. These are immune cells that attack harmful organisms in your dog’s gut, but they can cause vomiting and diarrhea when they become overactive. Diet and lifestyle changes will help this condition. Epilepsy Seizures and epilepsy can occur in Maltese as well. These conditions tend to be genetic, so if the dog’s parents or other direct relatives have a history of seizure, then your dog will have a higher chance of experiencing them. Because Maltese dogs have low body weight, they are at risk of experiencing hypoglycemic seizures. Hypoglycemic seizures are caused by low blood sugar levels. Seizures start as an excessive surge of electrical activity in the brain. The surge becomes excessive and overwhelms the neurons, resulting in a temporary malfunction of the brain. Depending on which regions of the brain are affected, a seizure manifests as muscle spasms or other symptoms. Knee Problems Sometimes your Maltese’s kneecap (patella) may slip out of place (called patellar luxation). You might notice that he runs along and suddenly picks up a back leg and skips or hops for a few strides. Then he kicks his leg out sideways to pop the kneecap back in place, and he’s fine again. If the problem is mild and involves only one leg, your friend may not require much treatment beyond arthritis medication. When symptoms are severe , surgery may be needed to realign the kneecap to keep it from popping out of place. Heart murmurs, congestive heart failure This is most often seen with senior Maltese dogs age 10 and up. Because heart murmurs rarely have any outward signs, this is usually discovered during a wellness check when the veterinarian is listening to the dog’s heart. Murmurs do not always lead to congestive heart failure, but they can. These are graded on a scale from 1 to 6. Typically no treatment is required for a grade 1 to 3 murmur. However, this is often a progressive disease. If the murmur worsens to a grade 4, 5, or 6, there can be issues such as troubled breathing, coughing, and exercise intolerance. Sources: https://www.dailypaws.com/dogs-puppies/dog-breeds/maltese https://www.petmaltese.com/maltese-health https://www.holistapet.com/maltese-dog-breed-temperament-personality/ Photo credit: https://thehappypuppysite.com/maltese-lifespan/ https://maltaangelmaltese.com/about-us/