Table of Contents

1. Why “Antibiotic Rank” Matters in Veterinary Medicine

Defining antibiotic ranking in veterinary antimicrobial stewardship

In veterinary antimicrobial stewardship, antibiotic ranking refers to the structured classification of antimicrobial agents based on their public health importance, therapeutic value in animals, and the potential risk they pose for driving antimicrobial resistance. These ranking systems create a shared scientific framework that identifies which antibiotics should be preserved, which require caution, and which remain suitable as first-line options for veterinary use.

International authorities guide this process. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE) publishes a List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance, while the European Medicines Agency’s Antimicrobial Advice Ad Hoc Expert Group (AMEG) categorizes antibiotics into risk-based groups intended to harmonize stewardship across the European Union. Collectively, these systems promote the rational and judicious use of antimicrobials in animals.

How ranking frameworks help veterinarians choose antibiotics responsibly

Antibiotic ranking systems function as practical decision tools for veterinarians. By stratifying antimicrobials according to their criticality, these frameworks:

- Highlight drugs that require strict restraint

- Direct clinicians toward lower-risk first-line options

- Support evidence-based prescribing

For example, the AMEG classification guides veterinarians by designating high-risk agents in Category B (Restrict), which should only be used when no suitable alternatives exist. This structured hierarchy helps balance animal welfare with the responsibility to limit the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

One Health context: linking animal use to human and environmental resistance risks

Antibiotic ranking is fundamentally shaped by the One Health perspective, which recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and the environment forms an interconnected system. Antimicrobial use in animals can influence resistance patterns in human pathogens through several pathways, including food production, environmental contamination, and direct human–animal interactions.

Because antibiotic use in one sector can amplify resistance risks across the entire ecosystem, global organizations emphasize the need for coordinated stewardship across species. Updated scientific opinions, such as those issued by the EMA’s AMEG or WOAH’s expert panels, explicitly address how antibiotic choices in veterinary medicine affect both animal health and public health. In this context, responsible prescribing in animals becomes an essential contribution to preserving the long-term effectiveness of antimicrobial agents worldwide. (European Medicines Agency & AMEG, 2024; World Organisation for Animal Health, 2021).

2. What “Antibiotic Rank” Means in Veterinary Medicine

In veterinary medicine, antibiotic ranking refers to the structured classification of antimicrobial agents based on their therapeutic importance, public health relevance, and the potential risks associated with their use. These systems create a risk-based categorization framework that guides veterinarians in the rational use of antimicrobials across all animal sectors.

International bodies have established standardized frameworks to support responsible prescribing. The WOAH (formerly OIE) List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance and the AMEG classification are two of the most widely recognized systems. Both frameworks rely on specific scientific criteria to determine how antibiotics should be prioritized for use in animals.

Key Criteria Used in Veterinary Antibiotic Ranking

- Public health importance of the antibiotic class

Ranking systems evaluate how the use of a particular antimicrobial in animals may affect human health. Antibiotic classes that are critically important to human medicine are placed into higher-risk categories, emphasizing that their veterinary use should be limited and carefully justified. - Risk of resistance transfer to humans

Antimicrobial resistance moves across species, ecosystems, and food systems. Ranking frameworks incorporate the likelihood that resistance genes selected in animals could reach human populations through direct contact, the food chain, or environmental pathways. AMEG specifically provides updated scientific advice that incorporates risks to both public health and animal health. - Therapeutic necessity in animals

Some antimicrobial classes are essential for maintaining animal welfare. The WOAH list identifies drugs of clear veterinary importance, recognizing that certain infections in livestock and companion animals cannot be effectively managed without them. Ranking systems balance this therapeutic need with the potential broader risks associated with drug use.

• Availability of suitable alternatives

Antibiotic ranking promotes responsible antimicrobial selection by encouraging the use of lower-risk alternatives whenever they provide adequate therapeutic benefit. By defining clear categories, frameworks help veterinarians reserve higher-risk or human-critical agents for cases where no appropriate alternatives exist, supporting the rational use of antimicrobials in daily practice.

3. Understanding the EMA AMEG Antibiotic Categorization System

The Antimicrobial Advice Ad Hoc Expert Group (AMEG) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) defines a risk-based antibiotic categorization system that guides the prudent and responsible use of antimicrobials in animals. This system evaluates both the public health consequences of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) arising from veterinary use and the therapeutic necessity of these drugs for maintaining animal health.

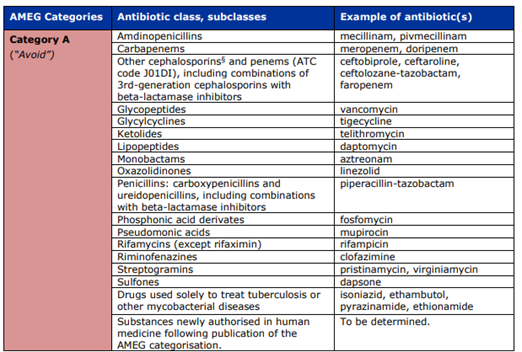

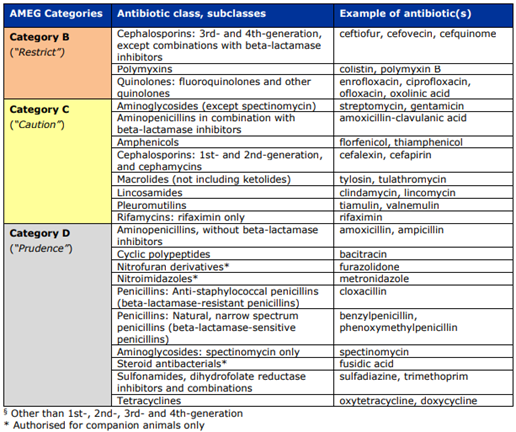

AMEG stratifies antimicrobials into four categories, ranging from A to D, with Category A representing the highest public health risk and Category D representing the lowest.

Category | Risk Level / AMEG Meaning | Veterinary Directive | Examples of Antibiotic Classes | Use Context |

Category A – Avoid | Highest risk, reserved exclusively for human medicine | Not authorized for veterinary use in the EU. May only be used in companion animals in exceptional cases and only under the prescribing cascade. Absolutely prohibited in food-producing animals. | Carbapenems (meropenem, doripenem), glycopeptides (vancomycin), oxazolidinones (linezolid), select advanced cephalosporins/penems reserved for human therapy. | Human-only antibiotics where veterinary use could severely compromise public health. |

Category B – Restrict | Critically important for human medicine | Use only when no effective Category C or D alternatives exist. Veterinary use must be justified. | Diagnostic requirement: Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) recommended before use. | Fluoroquinolones (enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin), 3rd–4th gen cephalosporins (ceftiofur, cefquinome), polymyxins (colistin, polymyxin B). |

Category C – Caution | Medium risk; human alternatives available but limited veterinary alternatives | Use only when Category D drugs would not provide adequate clinical efficacy. | Macrolides (tylosin, tulathromycin), aminoglycosides except spectinomycin (gentamicin, streptomycin), 1st–2nd gen cephalosporins, aminopenicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors (amoxicillin–clavulanic acid). | Provides options for cases where first-line agents may be ineffective. |

Category D – Prudence | Lowest public-health risk | Recommended as first-line options when clinically appropriate. Avoid overuse, long treatment durations, and routine group treatments unless individual treatment is not feasible. | Penicillins (amoxicillin, benzylpenicillin), tetracyclines (oxytetracycline, doxycycline), sulfonamides including potentiated combinations (sulfadiazine + trimethoprim). | Preferred choices for general veterinary practice with prudent use principles. |

Diagnostic Tools and Responsible Prescribing

The AMEG framework emphasizes that diagnostic confirmation is essential, particularly before escalating to Category B or C antibiotics. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) is central to this approach, ensuring that veterinarians prescribe the narrowest effective agent.

Tools such as the miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test analyzer support these principles by rapidly determining susceptibility profiles (S, I, R) from clinical samples. By identifying whether a Category D antibiotic remains effective, the miniAST system helps reduce unnecessary exposure to higher-risk agents and strengthens antimicrobial stewardship at the farm or clinic level.

4. WOAH and FAO Frameworks for Veterinary Antibiotic Ranking

The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) play central roles in shaping how antibiotics are ranked and regulated in veterinary medicine. Their work is aligned with the One Health framework, which recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is interconnected. Through international standards and coordinated guidance, these organizations influence national policies, veterinary prescribing practices, and global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mitigation strategies.

Comparison of Veterinary and Human Ranking Frameworks

The table below provides an integrated view of how WOAH, WHO, and the European Medicines Agency’s AMEG framework categorize antibiotics for stewardship across sectors.

Table 1. Comparison of Antibiotic Ranking Frameworks: WOAH vs WHO vs AMEG

Framework | Purpose | Primary Focus | Ranking Categories | How Categories Guide Use | Examples of Antibiotic Classes |

WOAH | Guide responsible veterinary antimicrobial use and reduce AMR transmission to humans | Veterinary health, public health risk from animal antibiotic use | VCIA, VHIA, VIA | VCIAs should not be used for prevention or first line therapy. Use ideally guided by culture and AST. | VCIA: fluoroquinolones, 3rd–4th gen cephalosporins, colistin |

WHO | Protect antibiotics essential in human medicine | Human health, global AMR control | CIA, HIA, IA | CIAs require strict global stewardship. Intended to preserve last line therapies. | CIAs: carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, polymyxins |

AMEG (EMA) | Balance public health risk with veterinary therapeutic need in EU | Veterinary regulation, public health | A Avoid, B Restrict, C Caution, D Prudence | A: no veterinary use except exceptional cases; B: use only if no C or D option works; D: first line choices with prudent use | A: carbapenems; B: fluoroquinolones, 3rd–4th gen cephalosporins, polymyxins; D: penicillins, tetracyclines |

WOAH List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance

WOAH maintains the List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance, which serves as a global reference for responsible antimicrobial selection in animals. The list is updated periodically to reflect emerging scientific evidence, resistance trends, and veterinary therapeutic needs. It emphasizes that the use of antimicrobial classes that are critical in human medicine must be approached cautiously in animals, especially when no alternatives exist.

WOAH also advises careful evaluation of any antimicrobial class used exclusively for human medicine before considering authorization or off label use in animals. This protects the long term efficacy of treatments for human infections.

WOAH Veterinary Importance Categories

WOAH ranks antimicrobial classes using two criteria:

- Criterion 1: Importance of the antimicrobial based on input from WOAH member countries.

- Criterion 2: Essentiality of the antimicrobial for treating serious animal diseases, and whether alternatives exist.

The categories are:

- Veterinary Critically Important Antimicrobials (VCIA): Both criteria met. These agents are vital for animal health and carry significant public health relevance.

- Veterinary Highly Important Antimicrobials (VHIA): One criterion met.

Veterinary Important Antimicrobials (VIA): Neither criterion met.

Veterinary Critically Important Antimicrobials

VCIAs include:

- third and fourth generation cephalosporins

- fluoroquinolones

- colistin

These agents should not be used for prevention and should not be first line options. Their use should ideally be supported by microbiological culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST).

FAO–WOAH–WHO Tripartite AMR Guidance

WOAH collaborates with FAO and WHO under the Tripartite partnership, a global initiative that coordinates AMR policy across human, veterinary, agricultural, and environmental sectors.

Foundations of Antibiotic Ranking

The WHO list of Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine was developed during early Tripartite consultations. WOAH created its veterinary list to complement it, ensuring that antibiotic ranking balances animal health needs with public health protection.

One Health Coordination

The Tripartite partnership works to:

- harmonize global AMR surveillance

- establish prudent use standards

- coordinate stewardship strategies across livestock, aquaculture, companion animals, and human medicine

This acknowledges that antimicrobial use in animals can influence resistance patterns in both humans and the environment.

Implementation and Best Practice

WOAH supports member countries in implementing:

- prudent antimicrobial use guidelines for terrestrial and aquatic animals

- laboratory standards for AST

- farm level AMR mitigation practices

These tools help countries develop national action plans that align with global expectations.

Relevance to Global Regulation, Trade, and AMR Control

WOAH and WHO antibiotic rankings shape both national regulations and international trade standards.

Regional Policy Influence

The European Medicines Agency (EMA), for example, used WHO and WOAH lists to develop the AMEG A–D categorization. This framework explicitly integrates both human and veterinary priorities.

Risk Management

High risk antibiotics that contribute substantially to human resistance, such as fluoroquinolones, third and fourth generation cephalosporins, and polymyxins, carry strict stewardship requirements worldwide.

Trade Implications

Although WOAH does not advocate complete bans on antibiotic use in animals, citing risks to animal welfare and food security, many importing countries enforce standards aligned with WOAH and WHO guidance. Examples include:

- EU prohibition of antibiotics for growth promotion

- WOAH aligned frameworks adopted by major food exporting countries

These standards influence production practices, residue monitoring, and veterinary drug approvals.

5. How Antibiotic Ranking Guides Veterinary Prescribing Decisions

The antibiotic ranking framework established by EMA AMEG is a central tool for supporting veterinarians in choosing antimicrobials responsibly. The framework provides a structured hierarchy that balances the need to treat animal disease with the obligation to minimize antimicrobial resistance (AMR) risks to humans, animals, and the environment, consistent with the One Health approach. Veterinarians are encouraged to consult these categories before prescribing.

5.1 Treatment Selection

AMEG categorization is designed to guide the sequence in which antibiotics should be considered, distinguishing first line options from last resort agents.

A structured hierarchy for antimicrobial selection

- Category D (“Prudence”) contains the lowest risk agents and is designated as the first line choice whenever possible. These antimicrobials are associated with a lower risk of selecting for resistance that threatens human medicine.

- Category C (“Caution”) should be used only when Category D substances would not be clinically effective, reflecting a stepwise escalation in risk.

- Category B (“Restrict”) includes Highest Priority Critically Important Antimicrobials (HP CIAs) for human medicine. These should be considered only when no effective options remain in Categories C or D, and use should be guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) whenever possible.

This hierarchical approach is reinforced by regional surveillance data. For example, Europe saw a 44 percent reduction in antibiotic consumption in food producing animals between 2014 and 2021, demonstrating that structured stewardship policies can reduce unnecessary exposure to higher risk classes.

5.2 Preventing Zoonotic Resistance Spread

One of the primary aims of AMEG categorization is to protect public health by reducing the selective pressure that drives zoonotic AMR transmission.

Minimizing exposure to human critical classes

- Category B contains HP CIAs such as fluoroquinolones, third and fourth generation cephalosporins, and polymyxins (colistin). These are essential last line agents in human medicine. Their veterinary use is tightly restricted to reduce selection pressure that could drive resistance transmission through food chains, direct contact, or environmental routes.

- Category A (“Avoid”) covers antibiotic classes reserved exclusively for human medicine, such as carbapenems, glycopeptides, and oxazolidinones. These substances are not authorized for veterinary use in the EU, and are completely prohibited in food producing animals. Limited use in companion animals is allowed only under strict cascade conditions.

Safeguarding last line antibiotics

To protect drugs critical for severe human infections:

- HP CIAs in Category B must not be used prophylactically or as first line treatment.

- In poultry production, the use of WHO HP CIAs is strongly discouraged and should be avoided to safeguard their efficacy in human medicine.

- WOAH guidance for Veterinary Critically Important Antimicrobials (VCIAs), such as fluoroquinolones and colistin, states that their use should ideally be supported by culture and AST.

Together, these measures limit the emergence and spread of zoonotic resistant pathogens.

5.3 Herd Health and Companion Animals

Antibiotic ranking systems also guide prudent antimicrobial use in herd management and companion animal practice, where the goal is to treat disease effectively while minimizing selection pressure.

Reducing unnecessary prophylaxis and metaphylaxis

Under Regulation (EU) 2019/6 and the principles established by AMEG, the use of antimicrobials for prophylaxis and metaphylaxis is tightly controlled to reduce unnecessary exposure and slow the development of resistance. Prophylactic treatment is limited to exceptional, high-risk situations and must be given only to individual animals, while metaphylaxis is permitted solely when there is a clear risk of disease spread and no suitable alternatives exist. Even for Category D antibiotics, which pose the lowest public-health risk, group treatments are allowed only when individual therapy is impractical, reinforcing the priority of targeted, rather than blanket, antimicrobial use. In addition, veterinarians are expected to support evidence-based dosing by optimizing dose, duration, and administration practices—avoiding unnecessary treatments, prolonged courses, and insufficient dosing that can foster resistance. AMEG guidance further emphasizes selecting administration routes that limit exposure of the gut microbiota, a major reservoir for antimicrobial resistance, favoring local or parenteral individual therapy over mass oral medication delivered through feed or water.

6. How Veterinary Antibiotic Use Shapes the Resistance Ecosystem

The necessity of antibiotic ranking systems and responsible prescribing arises directly from the One Health understanding that the health of humans, animals, and the environment forms a connected resistance ecosystem. Antibiotic use in animals alters microbial populations, selects for resistant strains, and allows resistance genes to move along food production chains, environmental pathways, and direct contact routes. These interconnected flows can ultimately compromise human health.

6.1 Food Chain Transmission: Meat, Milk, and Eggs

Antibiotic use in livestock increases the abundance of resistant bacteria in the animal gut, which can then enter the human population through food consumption.

Food as a major route of human exposure

- Foodborne transmission is considered a major AMR exposure route in industrialized countries.

- Resistant pathogens such as Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, and Yersinia enterocolitica can contaminate meat, milk, eggs, and poultry products.

- Campylobacter species are efficiently transmitted to humans via food of animal origin and are a particularly relevant example of zoonotic transfer.

- Ingestion of resistant bacteria enables colonization of the human gut microbiome, which can lead to infections that are more difficult to treat.

Contaminated animal products

Dairy products, minced beef, and poultry are among the most frequently contaminated commodities. WOAH’s list of veterinary antimicrobials includes risk management guidance intended to prevent contamination of animal products such as meat, milk, eggs, and honey with antimicrobial residues or resistant organisms.

6.2 Environmental Pathways: Manure and Water Runoff

The environment serves as a reservoir and conduit for resistant bacteria and resistance genes generated through agricultural antibiotic use.

Excretion and environmental loading

A substantial proportion of veterinary antimicrobials—often between 40 and 90 percent of the administered dose—is excreted in urine or feces in unmetabolized or biologically active forms. As a result, animal manure functions much like human sewage, carrying both antimicrobial residues and resistant bacteria into the environment and creating a persistent ecological reservoir that drives further resistance selection.

Spread through agricultural practices

When animal manure is stored or applied as fertilizer, resistant bacteria and antimicrobial residues can transfer into crops and enter surface waters through agricultural runoff. Studies have confirmed that antibiotic residues can be detected in plants grown in fertilized soils as well as in runoff from manure-treated land, demonstrating how these compounds persist beyond the farm environment. This environmental dissemination alters soil and water microbiomes, creating secondary ecological reservoirs that can reintroduce resistant bacteria into both animal and human populations, reinforcing the interconnected risks emphasized by the One Health framework.

Regulatory considerations

To address these environmental impacts, national AMR frameworks must incorporate environmental legislation, such as the Water Framework Directive, to control contamination pathways.

6.3 Human–Animal Transmission: Handlers, Livestock, and Pets

Direct contact allows resistant organisms to move between humans, livestock, and companion animals.

Occupational exposure risks

- Resistant bacteria, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), are readily transmitted between animals and humans through physical contact.

- Livestock handlers, farm laborers, and veterinarians face significantly elevated risks.

- Livestock-associated MRSA (LA MRSA) infection is estimated to be 9.64 times more likely in exposed livestock workers and veterinarians compared with individuals without animal contact.

Bidirectional flow of resistance

Transmission is not solely animal to human. Human to animal transfer has been documented, including the introduction of LA MRSA into sow farms through colonized personnel.

Companion animals

Restrictions applied to livestock antimicrobials are increasingly extended to pets, due to the capacity of dogs and cats to share resistant organisms with their owners. Surveillance systems must therefore incorporate companion animals into AMR monitoring programs.

6.4 Why Unified Stewardship Policies Are Essential

The interconnected nature of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) means that meaningful mitigation requires coordinated interventions across all sectors, an approach central to the One Health framework. The WHO, FAO, and WOAH Tripartite collaboration emphasizes multisectoral cooperation to harmonize risk-management strategies spanning human medicine, veterinary practice, agriculture, and environmental stewardship. Within this structure, policy tools such as the AMEG antibiotic categorization system guide veterinarians toward prudent prescribing choices and work in parallel with Regulation (EU) 2019/6, which imposes strict limitations on prophylactic and metaphylactic antimicrobial use. Unified antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) policies are essential to preserve the long-term efficacy of available drugs. The global stakes are substantial, with unchecked antimicrobial consumption projected to cause up to USD 100 trillion in economic losses by 2050, underscoring the urgency of coordinated action. Cross-country cooperation, evidence sharing, and harmonized surveillance systems further advance international objectives such as the European Green Deal’s Farm to Fork strategy, which aims to reduce veterinary antimicrobial sales by 50 percent by 2030.

7. Role of AST in Supporting Antibiotic Ranking

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) is a central component of responsible antibiotic use in veterinary medicine. Ranking systems such as the EMA’s AMEG categories and the WOAH list depend on AST to ensure that antibiotics are prescribed based on evidence of clinical effectiveness and risk. AST therefore provides the operational link between antimicrobial stewardship frameworks and day to day veterinary decision making.

7.1 How AST Supports Ranking Decisions

The AMEG categorization system integrates susceptibility data directly into its recommendations, especially for antibiotics that pose greater risks to public health.

Restricted categories depend on AST for justification

- Category B (Restrict) and Category C (Caution)

- Category B antimicrobials should be reserved for situations in which no suitable options from Categories C or D can provide adequate clinical efficacy.

- Their use should be guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing whenever feasible to ensure that treatment is justified and appropriately targeted.

- Category C antibiotics should only be used when there is no effective Category D option, and AST provides the evidence needed to confirm this.

- WOAH recommendations for Veterinary Critically Important Antimicrobials (VCIAs)

WOAH advises that VCIAs should not be used for prevention and should not be first line agents. Their use should ideally be guided by culture and susceptibility testing, reinforcing the same principles reflected in AMEG.

Supporting clinical judgment and on farm monitoring

Regular bacteriological testing enables veterinarians to identify the causative organism, determine whether a first-line antimicrobial will be effective, monitor resistance patterns at the farm level, and refine antimicrobial use policies over time.

The AMEG classification is not a treatment guideline, but it provides a structured risk framework that veterinarians apply together with AST results to ensure prudent prescribing under the veterinary “cascade”.

7.2 How Phenotypic and Molecular Diagnostic Tools Strengthen Antibiotic Selection

Rapid diagnostic testing plays a central role in antimicrobial stewardship by enabling evidence-based treatment decisions, reducing unnecessary exposure to higher-risk antibiotics (particularly Category B), and ensuring that prescriptions align with AMEG’s hierarchy of preferred veterinary antimicrobial choices. Bioguard’s miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer supports this stewardship framework through objective, phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), allowing veterinarians to avoid unwarranted escalation to critically important antimicrobials and to treat infections with greater precision and confidence.

The miniAST uses a broth microdilution phenotypic method, detecting bacterial growth through colorimetric change. This approach directly measures an organism’s functional susceptibility to each antibiotic, reflecting all mechanisms of resistance—including those not captured genetically—and adhering to CLSI and EUCAST principles for MIC-based interpretation. Phenotypic AST remains essential in clinical decision-making because it determines whether a pathogen is truly treatable with a selected drug.

Molecular diagnostics provide complementary insight by detecting specific resistance genes, such as mcr (polymyxin resistance), cfr and optrA (oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance), and plasmid-mediated ESBL genes. While gene detection helps predict resistance potential and informs surveillance and biosecurity measures, molecular findings do not always correlate with phenotypic susceptibility. Thus, molecular detection enhances but does not replace the need for phenotypic AST in guiding clinical therapy.

The miniAST delivers rapid, clinically actionable results—sometimes in as little as six hours, and typically within 8 to 24 hours, depending on the organism. This accelerated turnaround reduces reliance on empirical prescribing and enables earlier initiation of targeted therapy. Results are presented clearly as S (Susceptible), I (Intermediate, high dose recommended), and R (Resistant), guiding veterinarians toward appropriate drug selection and dosing strategies. AST is particularly recommended when multidrug-resistant organisms are suspected, when empirical therapy has failed, or when the infection is severe or life-threatening.

Through its rapid analysis and clinically relevant phenotypic data, miniAST directly supports AMEG’s emphasis on responsible prescribing, ensuring that Category B and C antimicrobials are used only when justified and that the lowest-risk effective option is chosen whenever possible.

8. Global Policy and Surveillance Systems

Global policy and surveillance systems form the backbone of the One Health response to antimicrobial resistance (AMR). These systems ensure coordinated action across human, veterinary, and environmental sectors, linking how antibiotics are classified, monitored, and regulated worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) are central to this global architecture, each contributing complementary roles in classification, guidance, and data collection.

8.1 WHO AWaRe Classification and its Overlap with Veterinary

Ranking

The EMA’s AMEG categorization system is intentionally aligned with WHO’s frameworks for human medicine, ensuring that veterinary prescribing remains consistent with global public health priorities.

WHO Classification Systems

WHO maintains two major antibiotic classification tools that have strong relevance for veterinary stewardship:

- Critically Important Antimicrobials (CIA List)

Categorized as Critically Important, Highly Important, or Important for human medicine. Within CIAs, the Highest Priority Critically Important Antimicrobials (HPCIAs) include quinolones, higher generation cephalosporins, macrolides and ketolides, polymyxins, and glycopeptides. - AWaRe Classification (ACCESS, WATCH, RESERVE)

- ACCESS: First and second choice agents for common infections.

- WATCH: Higher resistance potential, limited use.

- RESERVE: Last resort antibiotics, including colistin and 4th/5th generation cephalosporins.

Alignment with Veterinary AMEG Categories

AMEG integrates both the WHO CIA and AWaRe lists to balance animal health needs with public health risks.

- Category B (Restrict) includes most WHO HPCIAs, such as fluoroquinolones, 3rd–4th generation cephalosporins, and polymyxins.

- Category A (Avoid) corresponds to WHO RESERVE drugs that are for human medicine only.

- Categories C and D reflect lower human public health risk and are preferred for routine veterinary use.

This alignment ensures that antibiotics essential for human medicine are preserved through controlled veterinary use.

8.2 WOAH Global Antimicrobial Use Systems

WOAH (formerly OIE) plays a foundational role in veterinary surveillance and guidance.

Veterinary Importance List

WOAH maintains the List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance, which classifies drugs as:

- Veterinary Critically Important (VCIA)

- Veterinary Highly Important (VHIA)

- Veterinary Important (VIA)

These classifications are based on therapeutic necessity in animals and the availability of alternatives, and they directly inform stewardship frameworks worldwide.

Surveillance and Standards

While the name “ANIMUSE” is not used in the source material, WOAH contributes through:

- Global standards for prudent antimicrobial use in terrestrial and aquatic animals

- Risk analysis and regulatory guidance within the Terrestrial Animal Health Code

- Encouraging member states to collect and report AMU data

- Recommending that VCIAs be used only with microbiological culture and susceptibility testing

These activities create the foundation for harmonized global monitoring.

8.3 FAO Surveillance Across the Food Chain

The FAO contributes through food chain monitoring and agricultural AMR guidance, recognizing that resistant bacteria often reach humans through contaminated food products.

Tripartite Coordination

Through collaboration with WOAH and WHO, FAO supports:

- surveillance of AMR in foodborne pathogens

- development of agricultural best practices

- regulation of antimicrobial use in food animal production

- risk communication across sectors

Food Safety Focus

FAO guidance reinforces monitoring of resistant zoonotic bacteria such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, and E. coli. These systems align with EFSA and ECDC monitoring efforts within the EU, creating a unified surveillance pipeline from farm to consumer.

8.4 Importance of Harmonized Reporting for AMR Containment

Standardized reporting is crucial for understanding global AMR trends and informing evidence based interventions.

EU Harmonization (ESUAvet)

Regulation (EU) 2019/6 introduced mandatory, harmonized reporting of veterinary antimicrobial use across all Member States. This replaced the voluntary ESVAC system and evolved into the ESUAvet annual surveillance report, supported by the ASU Platform for centralized data collection.

Integrated Surveillance

Data from ESUAvet and the mandatory EFSA–ECDC AMR monitoring programme feed directly into policy evaluation. Evidence shows that reductions in veterinary antibiotic use correlate with decreases in resistance among zoonotic and indicator bacteria in both animals and humans.

Global Reduction Targets

Harmonized reporting also supports international commitments such as the EU Farm to Fork target of halving veterinary antimicrobial sales by 2030. Without comparable and complete data across sectors, such goals would be impossible to implement or track.

To support responsible antibiotic use, Bioguard offers the miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer, a tool designed to help combat antimicrobial resistance with game-changing features:

Feature | Benefit |

Fast Results | Get results in just 6 hours, enabling swift and confident treatment. |

Automated Interpretations | Instantly deliver precise susceptibility profiles, supporting faster, more informed clinical decisions and optimizing patient care. |

Dual-Sample Testing | Double the efficiency with simultaneous analysis of two samples at once. |

High Accuracy | Achieve an impressive 92% accuracy rate compared to traditional disc diffusion tests. |

📌 Note for Veterinarians:

The miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer is available exclusively to licensed veterinarians and veterinary hospitals.

📩 How to Order MiniAST

To purchase MiniAST or request a quotation, please contact our sales team or email our customer service:

📧 service@bioguardlabs.com

☎️ Please include your hospital name and contact number so our sales representative can follow up with you directly.

References:

- Bioguardlabs. (2025). miniAST – Antibiotic Susceptibility Test analyzer.

- Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. (2018). Policy on Highest Priority Critically Important Antimicrobials. (iNAP).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. (2025, September 23). New European Partnership on One Health AMR: €253 million for research and innovation against antimicrobial resistance.

- European Medicines Agency. (2025). Categorisation of antibiotics in the European Union: Answer to the request from the European Commission for updating the scientific advice on the impact on public health and animal health of the use of antibiotics in animals (EMA/CVMP/CHMP/682198/2017-Rev1).

- European Medicines Agency. (2025). Infographic – Categorisation of antibiotics for use in animals for prudent and responsible use.

- European Medicines Agency. (2025, March 31). First report on EU-wide sales and use of antimicrobials in animals.

- International Poultry Council, & World Organisation for Animal Health. (2019). Best Practice Guidance to reduce the need for antibiotics in poultry production.

- McGrath, M. (2022). Prudent Prescribing of Antibiotics: Focusing on Intramammary Antibiotics. Veterinary Ireland Journal.

- Muska, A., Pilvere, I., Upite, I., Muska, K., & Nipers, A. (2025). Assessing European Union member states’ progress toward antimicrobial sales reduction targets under the European Green Deal: A comparative policy and performance analysis. Veterinary World, 18(9), 2746–2760.

- News Desk. (2024, February 22). EU report shows the impact of reduced antibiotic use. Food Safety News.

- Veterinary Antimicrobial Guidance and Categorization Sources. (2025).

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/categorisation-antibiotics-european-union-answer-request-european-commission-updating-scientific-advice-impact-public-health-animal-health-use-antibiotics-animals_en.pdf

- WOAH List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance (2019); WHO Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine, 6th rev. (2019); WHO AWaRe Classification (2023); EMA/EFSA AMEG Categorization (2019; 2020).