Table of Contents

Maigan Espinili Maruquin

1. Introduction

Overview of Bartonella henselae as a Significant Feline and Zoonotic Pathogen

Bartonella henselae is a small, fastidious, Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium with a global distribution. It exhibits a marked tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes, enabling the establishment of chronic, relapsing bacteremia that may persist for months or even years in infected hosts.

Domestic cats are the primary mammalian reservoir and represent the principal source of zoonotic transmission to humans. Kittens and feral cats typically harbor higher bacterial loads, although subclinical infection is widespread across the global feline population. Reported bacteremia prevalence in apparently healthy cats ranges from 8% to 56%, depending on geographic region and flea exposure. The primary competent vector for B. henselae is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), within which the organism replicates in the flea gut and is excreted in flea feces (commonly referred to as flea dirt). These contaminated feces can remain infectious in the environment for at least nine days, facilitating indirect transmission.

Importance in Companion Animal Medicine and Public Health

From a companion animal medicine perspective, B. henselae is clinically significant because most infected cats function as asymptomatic carriers, silently sustaining zoonotic risk. Nevertheless, increasing evidence links B. henselae infection to sporadic but severe feline disease manifestations, including endocarditis, myocarditis, and ocular inflammatory conditions such as uveitis. In dogs, which are considered accidental hosts, bartonellosis is often more pathogenic and has been strongly associated with culture-negative endocarditis and granulomatous inflammatory disease.

In public health, B. henselae is best known as the primary etiological agent of Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) in humans. Transmission most commonly occurs when cat claws or oral cavities become contaminated with infected flea feces, which are then inoculated into human skin through a scratch or bite.

- Immunocompetent individuals typically develop a self-limiting illness characterized by regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and a papule at the site of inoculation.

- Immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients, are at risk for severe and potentially fatal complications, such as bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis, encephalitis, and endocarditis, reflecting the organism’s vasoproliferative potential.

Scope of the Review and Relevance to Clinical Practice

A clear understanding of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and persistence mechanisms of B. henselae is essential for effective clinical management and disease prevention. Diagnosis remains particularly challenging, as the organism is highly fastidious and slow-growing, frequently resulting in false-negative blood culture findings and so-called “culture-negative” infections. Although molecular assays such as PCR and serological testing are widely employed, interpretation is complicated by intermittent bacteremia and the high background seroprevalence among healthy cats.

In clinical practice, adoption of a One Health framework is critical. Veterinarians play a central role in mitigating zoonotic risk through owner education, emphasizing strict, year-round flea control, appropriate hygiene, and cautious interaction with cats, especially in households containing immunocompromised individuals. Management is further complicated by the absence of a standardized antimicrobial protocol capable of reliably achieving complete bacteriological clearance in feline hosts.

To conceptualize its biological behavior, B. henselae may be likened to a “stealthy hitchhiker.” By residing within erythrocytes and vascular endothelium, the organism evades immune surveillance, periodically re-emerging only to secure transmission via a passing flea.

2. Characteristics and Epidemiology

2.1 Taxonomy and Microbiological Characteristics

The genus Bartonella comprises small, thin, fastidious, and pleomorphic Gram-negative bacilli. These organisms are facultative intracellular pathogens with a highly specialized biological niche characterized by a pronounced tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes (red blood cells). Following host entry, Bartonella spp. proliferate within membrane-bound vacuoles, often referred to as invasomes, inside vascular endothelial cells. Periodic release into the bloodstream allows subsequent invasion of erythrocytes, within which the bacteria may persist until cellular senescence or destruction occurs (Cunningham and Koehler 2000; LeBoit 1997).

Transmission is predominantly arthropod-borne, involving vectors such as fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), ticks, lice, and sand flies. Although Bartonella species have been isolated from a wide range of mammalian hosts, including rodents, rabbits, canids, and ruminants, domestic and feral cats represent the principal mammalian reservoir for the most epidemiologically and clinically significant zoonotic species, particularly B. henselae (Chomel et al., 1996; Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Guptill, 2012).

2.2 Global Distribution and Seroprevalence

Bartonella species exhibit a global distribution, although prevalence varies markedly according to environmental and ecological conditions. In European feline populations, reported antibody prevalence ranges from 8% to 53% (Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Zangwill, 2013), while global serological evidence of exposure in cats spans approximately 5% to 80% (Guptill, 2012).

The epidemiology of Bartonella infection is strongly influenced by geography, climate, and flea density. The highest prevalence rates are consistently observed in warm, humid temperate and tropical regions, where environmental conditions favor the survival and propagation of C. felis. In contrast, in colder climates, such as Norway, Bartonella infection in cats is reported to be rare or virtually absent, reflecting the limited persistence of flea vectors under such conditions.

2.3 Species Diversity and Genotypes

Although 22 to 38 Bartonella species have been described to date, Bartonella henselae remains the most frequently detected species in both domestic cats and humans. Feline populations may also harbor Bartonella clarridgeiae, identified in approximately 10% of infected cats, while B. koehlerae is detected far less commonly (Guptill, 2012). Considerable regional variation exists among B. henselae genotypes, which are broadly classified into Houston-1 (Type I) and Marseille (Type II) strains.

- Type II (Marseille) predominates among feline populations in the western United States, western continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

- Type I (Houston-1) is the dominant genotype in Asia, including Japan and the Philippines, and is most frequently isolated from human clinical cases worldwide, even in regions where Type II strains are more prevalent among cats.

Beyond domestic cats, Bartonella infections have been documented in non-domestic felids, including African lions, cheetahs, and various neotropical wild cat species, underscoring the broad ecological adaptability of the genus (Guptill, 2012).

To conceptualize its ecological behavior, Bartonella may be viewed as a “weather-dependent squatter.” It establishes itself most successfully in warm, densely populated environments rich in flea vectors, while struggling to persist in cold, sparsely populated regions where its preferred mode of transport cannot survive.

3. Transmission and Life Cycle

3.1 Vector-Mediated Transmission

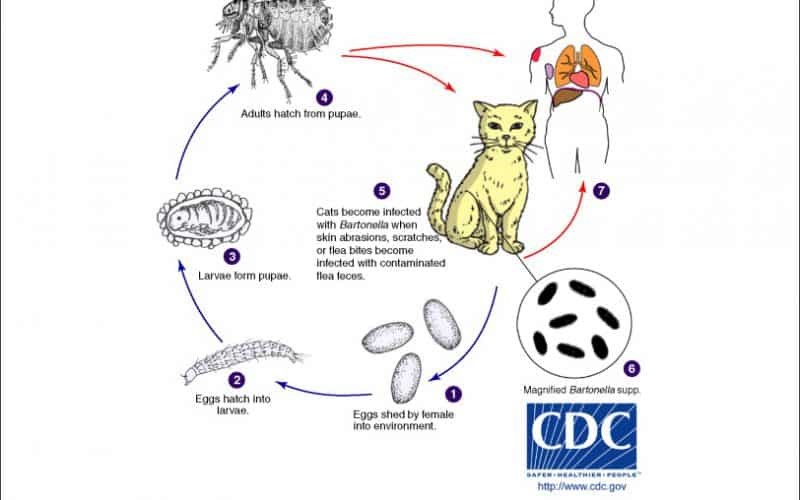

The cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis felis) is the primary competent vector for the transmission of Bartonella henselae. Flea infestation is essential for the maintenance of infection within feline populations, as direct cat-to-cat transmission does not occur in flea-free environments (Chomel et al., 1996). Transmission is initiated when a flea ingests bacteremic erythrocytes during a blood meal from an infected cat. Within the flea, B. henselae is not eliminated but instead replicates within the digestive tract, with marked amplification occurring in the hindgut (Finkelstein, Brown et al., 2002). The organism may also form biofilm-like aggregates within the flea gut, enhancing bacterial persistence.

3.2 Environmental Persistence and Indirect Transmission

Viable Bartonella organisms are subsequently excreted in flea feces, commonly referred to as flea dirt (Chomel et al., 1996; Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013). These organisms demonstrate notable environmental resilience, remaining viable and infectious within dried fecal material for approximately nine to twelve days (Finkelstein, Brown et al., 2002).

Transmission to mammalian hosts occurs predominantly via indirect inoculation. During normal grooming and scratching behaviors, cat claws become contaminated with infected flea feces, while grooming further distributes contaminated material to the oral cavity and teeth. The pathogen is then introduced into the skin of humans or other animals when a contaminated claw or tooth produces a scratch, bite, or superficial abrasion, providing direct access to the dermis and underlying tissues.

3.3 Alternative Transmission Routes

Although the flea-mediated cycle represents the dominant transmission pathway, alternative vectors and routes have been implicated. Several studies suggest that ticks (e.g., Ixodes ricinus) may act as competent vectors capable of maintaining B. henselae through transtadial transmission, with human cases reported following tick bites (Lucey, Dolan et al., 1992; Klotz, Ianas et al., 2011; Biancardi and Curi, 2014). Additional potential transmission routes include blood transfusion and accidental needle-stick injuries.

Human bartonellosis cases have been reported following tick bites, even in the absence of documented cat exposure. Additional potential transmission routes include blood transfusion from infected donors and accidental needle-stick injuries, particularly among veterinary and laboratory professionals, underscoring the occupational relevance of bartonellosis.

Figure 1. Life Cycle of Bartonella spp.

Fig. 1. The Life Cycle of Bartonella spp.

To conceptualize this transmission cycle, the cat flea may be regarded as a “biological factory.” It acquires raw materials in the form of infected blood, amplifies the pathogen along its internal assembly line within the hindgut, and releases the final product packaged in durable containers, flea feces, which persist in the environment until mechanically delivered by a cat’s claws or teeth.

4. Pathogenesis and Clinical Signs

4.1 Mechanisms of Infection

The primary route of Bartonella henselae infection is intradermal inoculation of contaminated flea feces, which gain access to the host through scratches, bites, or pre-existing skin abrasions. Following entry, the organism demonstrates a marked tropism for vascular endothelial cells and erythrocytes (red blood cells), a biological strategy that underpins its ability to establish persistent infection.

Immune evasion is achieved through a predominantly intracellular lifestyle (Cunningham and Koehler, 2000; LeBoit, 1997). By residing within erythrocytes, which lack MHC I molecules, B. henselae effectively avoids recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clinical expression of disease is therefore strongly influenced by host immune competence and bacterial species or strain.

In immunocompetent hosts, infection typically elicits a granulomatous inflammatory response, characterized histologically by areas of necrosis surrounded by histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. In contrast, immunocompromised individuals may develop severe vasoproliferative lesions, such as bacillary angiomatosis, driven by bacterial interference with host apoptotic pathways and sustained stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation.

4.2 Experimental Infections in Cats

Under experimental conditions, B. henselae infection in cats is predominantly subclinical, with most animals remaining clinically normal throughout the course of infection. However, disease severity is strain-dependent, reflecting variability in virulence factors among different isolates.

Reported clinical findings in experimentally infected cats include:

- Localized abscesses or papular lesions at inoculation sites

- Peripheral lymphadenomegaly

- Transient pyrexia, typically lasting 48–72 hours

- Mild neurological abnormalities, including altered behavior, staring episodes, or focal motor seizures

- Reproductive disturbances, including placental pathology and reproductive failure

- Transient anemia, lethargy, and reduced activity

(Kordick, Brown et al., 1999; Guptill, Slater et al., 1997; Stützer and Hartmeservoirsand

Histopathological examination frequently reveals follicular hyperplasia of lymph nodes and splenic tissue, accompanied by lymphocytic inflammation affecting organs such as the heart, liver, and kidneys, supporting the systemic nature of infection even in the absence of overt clinical signs (Guptill, 2012).

4.3 Natural Infections and Chronic Disease

In natural settings, the overwhelming majority of infected cats remain asymptomatic, functioning as persistent reservoirs of infection. These cases are characterized by chronic, relapsing bacteremia, during which B. henselae intermittently re-enters the circulation over periods ranging from weeks to several years (Chomel, Kasten et al., 1996; Finkelstein, Brown et al., 2002).

Despite the typically silent clinical course, B. henselae infection has been associated with several disease syndromes in cats:

- Chronic gingivostomatitis: Although an association has been proposed, controlled studies have yielded inconsistent findings, and a definitive causal relationship remains unproven.

- Endocarditis and myocarditis: Sporadic but well-documented cases involving valvular vegetations and myocardial inflammation have been confirmed using PCR, histopathology, and silver staining techniques.

- Immune complex-mediated disease and hyperglobulinemia: A significant correlation exists between Bartonella seropositivity and hyperglobulinemia, likely reflecting chronic antigenic stimulation and deposition of immune complexes within vascular or renal tissues.

5. Zoonotic Implications

Bartonella henselae as the Causative Agent of Cat Scratch Disease

Bartonella henselae (formerly Rochalimaea henselae) is the principal etiological agent of Cat Scratch Disease (CSD), a globally distributed zoonotic infection. Although CSD was clinically recognized as early as 1950, Bartonella species were not definitively identified as the causative organisms until 1983. In the United States alone, an estimated 12,000 to 20,000 cases are reported annually, with the highest incidence observed in children under 15 years of age. Disease prevalence is notably higher in warm and humid regions, conditions that favor the proliferation of flea vectors.

Transmission to Humans via Flea-Contaminated Scratches

Domestic cats, particularly kittens younger than one year, represent the primary mammalian reservoir for B. henselae. Zoonotic transmission occurs predominantly through the following routes:

- Flea-contaminated scratches: The most common mode of transmission involves scratches inflicted by cats whose claws are contaminated with infected flea feces from Ctenocephalides felis.

- Bites and oral contact: Transmission may also occur via bites or licking, as B. henselae can be present in the oral cavity following grooming behaviors.

- Potential arthropod vectors: While the cat–flea–cat cycle is central to maintenance of infection, accumulating evidence suggests that ticks (Ixodes ricinus), and possibly biting flies or spiders, may serve as alternative transmission vectors to humans.

(Chomel, Kasten et al., 1996; Lucey, Dolan et al., 1992).

Increased Disease Severity in Immunocompromised Hosts

The clinical outcome of B. henselae infection is strongly influenced by host immune competence:

- Immunocompetent individuals: Most cases present as a self-limiting illness, beginning with a papule or pustule at the site of inoculation, followed by regional lymphadenopathy, low-grade fever, and malaise.

- Immunocompromised individuals: Patients with advanced HIV infection (CD4 counts <100 cells/mm³), solid organ transplant recipients, or those undergoing chemotherapy are at significant risk for severe, disseminated disease. Documented manifestations include:

- Bacillary angiomatosis, characterized by proliferative vascular lesions of the skin or viscera.

- Bacillary peliosis, involving blood-filled cystic lesions of the liver or spleen.

- Culture-negative endocarditis, a life-threatening condition frequently missed by conventional diagnostic methods.

Public Health and Occupational Relevance

Bartonella henselae poses a substantial public health concern due to its high prevalence in domestic cat populations and its expanding spectrum of associated human diseases. Veterinary professionals and animal handlers represent a high-risk occupational group, consistently demonstrating higher seroprevalence rates than the general population as a result of repeated exposure to cats and arthropod vectors.

Beyond classical CSD, B. henselae has been increasingly implicated in atypical and systemic disease presentations, including:

- Ocular manifestations, such as neuroretinitis and Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome.

- Immune-mediated and autoimmune conditions, including glomerulonephritis, thyroiditis, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

Current public health recommendations emphasize strict, year-round flea control in domestic cats and advise that high-risk individuals adopt adult cats rather than kittens, as older cats are statistically less likely to exhibit persistent bacteremia.

From a zoonotic perspective, the cat flea may be viewed as a “biological ink cartridge.” It deposits contaminated flea feces onto the cat’s claws, transforming routine scratches into inadvertent inoculation events. Once introduced into human skin, the clinical consequences depend entirely on the effectiveness of the host’s immune surveillance and containment mechanisms.

6. Diagnosis

6.1 Indications for Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic evaluation for Bartonella infection should be considered in clearly defined clinical and epidemiological contexts. Testing is indicated in cats with a documented history of flea or tick exposure, particularly when accompanied by compatible clinical syndromes such as endocarditis, myocarditis, unexplained fever, or neurological abnormalities. Routine screening is strongly recommended for feline blood donors, given the risk of iatrogenic transmission through transfusion.

Testing is also warranted in clinically ill cats in which bartonellosis is included among the primary differential diagnoses, as well as in households where human Bartonella-associated disease has been confirmed. Special consideration should be given to cats owned by immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV infection, transplant recipients, or patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, as zoonotic transmission in these settings may result in severe or life-threatening disease.

6.2 Bacterial Culture

Bacterial culture remains the reference or “gold standard” for confirming active Bartonella infection. However, its clinical utility is limited by low sensitivity. Bartonella species are fastidious, slow-growing organisms and are characterized by relapsing, intermittent bacteremia, which reduces the likelihood of detection from a single blood sample.

Colonies may require 10 to 56 days to become visible on specialized media, such as chocolate agar. Consequently, culture is best reserved for clinically affected cats with strong suspicion of bartonellosis and may necessitate serial blood sampling over multiple days to improve diagnostic yield. The use of enrichment systems, particularly Bartonella Alpha Proteobacteria Growth Medium (BAPGM), has been shown to enhance isolation rates and is often combined with downstream PCR testing.

6.3 Molecular Diagnostic Techniques

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays provide a more rapid and sensitive means of detecting active Bartonella infection by identifying bacterial DNA. PCR testing can be performed on a variety of clinical specimens, including:

- Whole blood, the most commonly submitted sample

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

- Aqueous humor

- Tissue samples, such as lymph nodes, cardiac valves, liver, or spleen

Real-time PCR (qPCR) is increasingly favored due to its higher analytical sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional PCR. Importantly, amplified DNA products may be subjected to sequencing, allowing definitive species-level identification, which is particularly valuable in cases of endocarditis or systemic disease.

Despite these advantages, PCR results must be interpreted cautiously. False-negative results can occur when samples are collected during non-bacteremic phases, underscoring the benefit of repeat testing or combined diagnostic approaches.

6.4 Serological Testing

Serological assays available for Bartonella detection include indirect immunofluorescent antibody testing (IFAT), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), and Western blot. These tests are best utilized as adjunctive tools, primarily for excluding infection rather than confirming active disease.

- High negative predictive value: A negative serological result is highly reliable, with reported probabilities of 87% to 97% that the cat is not infected.

- Low positive predictive value: Positive results indicate previous exposure, not necessarily ongoing bacteremia, as antibodies may persist long after bacterial clearance.

- Seronegative bacteremia: Approximately 3% to 15% of bacteremic cats remain seronegative, likely due to immune evasion or delayed seroconversion.

For these reasons, serological testing is most effective when interpreted alongside PCR or culture results, rather than used in isolation.

7. Treatment and Management

7.1 Antimicrobial Therapy

A range of antimicrobial agents has been investigated for the treatment of feline Bartonella henselae infection, including doxycycline, amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, enrofloxacin, erythromycin, rifampicin, azithromycin, marbofloxacin, and more recently pradofloxacin. Despite this breadth of options, no antimicrobial regimen has consistently achieved complete eradication of bacteremia in naturally infected cats.

The principal obstacle to therapeutic success lies in the pathogen’s intracellular localization within erythrocytes and vascular endothelial cells, which effectively shields B. henselae from many antimicrobials that demonstrate in vitro activity but limited intracellular penetration. Additionally, the relapsing nature of bacteremia complicates assessment of treatment efficacy, as transient reductions in bacterial load may be misinterpreted as clearance.

Among available agents, doxycycline remains the preferred first-line therapy, supported by evidence suggesting that higher doses administered over extended durations (typically four to six weeks) are more effective in suppressing bacteremia. Combination therapy, particularly doxycycline with rifampicin, has shown benefit in canine bartonellosis involving the central nervous system. However, rifampicin use in cats is generally discouraged due to safety concerns and the risk of rapid resistance development.

Macrolides and fluoroquinolones, although frequently prescribed, are associated with rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance, especially during prolonged treatment courses. Fluoroquinolones (particularly enrofloxacin at high doses) further carry a recognized risk of retinal degeneration and irreversible blindness in cats, limiting their routine use. Collectively, current evidence supports a bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal outcome for most treatment protocols.

7.2 Indications for Treatment

Given the high prevalence of subclinical infection and the limitations of antimicrobial therapy, routine treatment of asymptomatic cats is not recommended. This approach aligns with contemporary principles of antimicrobial stewardship and reflects the lack of definitive evidence that treatment reliably eliminates zoonotic risk.

Treatment should be considered under the following circumstances:

- Clinically Affected Cats: Cats with confirmed or strongly suspected bartonellosis presenting with endocarditis, myocarditis, persistent fever, uveitis, or neurological signs warrant antimicrobial intervention.

- High-Risk Households: Treatment is recommended for cats living with immunocompromised individuals, including patients with HIV/AIDS, transplant recipients, or those undergoing chemotherapy, even in the absence of overt feline disease.

- Individualized Risk Assessment: Clinical decision-making should balance zoonotic risk against potential adverse effects, including esophageal strictures associated with doxycycline and fluoroquinolone-induced retinal toxicity. Importantly, owners should be counseled that successful treatment does not guarantee elimination of future transmission risk.

7.3 Prevention and Control

From both veterinary and public health perspectives, prevention remains the most effective strategy for managing B. henselae infection. Strict, year-round flea and tick control is essential and should be implemented using veterinarian-approved topical, oral, or collar-based ectoparasiticides. Permethrin-containing products are contraindicated in cats and must never be used.

Additional preventive measures include maintaining cats indoors, which significantly reduces exposure to ectoparasites and contact with potentially bacteremic animals. To minimize zoonotic transmission, particularly Cat Scratch Disease, owners should be advised to:

- Avoid rough play, especially with kittens

- Supervise interactions between cats and young children

- Perform immediate wound cleansing with soap and water following scratches or bites

- Maintain regular nail trimming

- Preferentially adopt healthy adult cats (>1 year of age) for immunocompromised households, as kittens demonstrate higher rates of bacteremia

8. One Health Perspective

Intersection of Feline Health, Vector Ecology, and Human Disease

Bartonella henselae represents a paradigmatic One Health pathogen, whose persistence and transmission depend on the dynamic interaction between animal reservoirs, arthropod vectors, environmental conditions, and human hosts. Domestic and feral cats function as the primary mammalian reservoir, sustaining prolonged, often asymptomatic bacteremia that facilitates silent maintenance of the organism within feline populations.

At the ecological level, the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) constitutes the principal biological amplifier of infection. Flea population density is strongly influenced by climatic variables, particularly temperature and humidity, explaining the markedly higher prevalence of feline infection and human Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) in tropical and warm-temperate regions. Within the flea, B. henselae replicates in the hindgut and is shed into the environment via infected flea feces, which serve as the dominant infectious substrate.

Human infection arises at the behavioral interface between cats and people. Through grooming and scratching, flea feces contaminate claws, oral cavities, and teeth, enabling inoculation into human skin via scratches, bites, or pre-existing abrasions. The expanding recognition of alternative vectors, notably ticks (Ixodes ricinus), further complicates the epidemiological landscape, as these arthropods may transmit Bartonella directly through salivary secretions, bypassing the traditional cat-flea-scratch pathway.

Collectively, these interactions illustrate how environmental suitability, vector competence, reservoir biology, and human behavior converge to sustain zoonotic transmission.

Importance of Integrated Veterinary and Medical Collaboration

The effective management of bartonellosis necessitates a coordinated One Medicine framework, bridging veterinary practice, human healthcare, and public health systems.

- Enhanced Clinical Recognition: In human medicine, bartonellosis frequently manifests as culture-negative disease, particularly endocarditis. Accurate diagnosis often hinges on the inclusion of animal exposure history. Documented cases demonstrate that identification of B. henselae infection has only been achieved after recognition of recent contact with cats, prompting targeted serological or molecular testing.

- Occupational Risk Management: Veterinary professionals experience disproportionately high seroprevalence, in some studies exceeding 70%, reflecting sustained exposure to infected animals and arthropod vectors. This underscores the need for occupational education, personal protective practices, and routine ectoparasite control in clinical settings.

- Public Health Education: Veterinarians occupy a critical frontline role in zoonotic disease prevention. Owner education regarding continuous flea and tick control remains the most effective and evidence-based strategy for reducing both feline infection rates and human disease incidence.

- Comparative Pathobiology: Across species, Bartonella infection produces convergent pathological outcomes, including endocarditis, myocarditis, vasculoproliferative lesions, and granulomatous inflammation. Comparative research across feline, canine, and human hosts has expanded understanding of Bartonella as a potential trigger of immune-mediated and autoimmune conditions, such as glomerulonephritis.

- Blood Donation Safety: The intraerythrocytic nature of Bartonella raises shared concerns in both veterinary and human transfusion medicine. Collaborative development of donor screening strategies is essential to mitigate the risk of iatrogenic transmission, particularly in immunocompromised recipients.

From a One Health standpoint, Bartonella henselae functions less as an isolated pathogen and more as a networked biological system, sustained by environmental permissiveness, vector efficiency, reservoir tolerance, and human proximity. Containment therefore cannot rely on medical treatment alone.

Interrupting transmission at the vector–reservoir interface, through integrated veterinary and public health action, remains the most effective means of protecting animal and human health alike.

9. Summary

Bartonella henselae is a globally distributed, fastidious zoonotic pathogen, with prevalence in healthy feline populations ranging from 5% to 80% worldwide. Approximately 8% to 56% of clinically healthy cats are actively bacteremic, yet most remain asymptomatic, serving as silent reservoirs for human and animal transmission. Environmental factors, particularly warm and humid climates conducive to high flea densities, strongly influence prevalence, whereas the pathogen is virtually absent in colder regions such as Norway.

Clinical detection of bartonellosis remains challenging due to intermittent or relapsing bacteremia. Single negative blood cultures or PCR tests cannot definitively rule out infection, and culture methods are hampered by the bacteria’s slow growth and fastidious requirements, often taking 6–8 weeks for detectable colonies. Serological testing, while valuable for ruling out infection due to its high negative predictive value (87–97%), cannot reliably confirm active infection. Consequently, diagnosis often relies on clinical suspicion, exclusion of other causes, and response to therapy, especially in symptomatic cats presenting with endocarditis, uveitis, or systemic inflammatory signs.

Emphasis on Vector Control and Risk-Based Management

Given the absence of a fully effective antimicrobial regimen to eliminate bacteremia, prevention remains the cornerstone of control. Strict, year-round flea and tick management is the most effective intervention to interrupt transmission cycles and protect both cats and humans. Clinical treatment is guided by risk, focusing on:

- Clinically ill cats, particularly those with endocarditis, myocarditis, or ocular inflammation.

- Cats living with immunocompromised individuals or young children, who are most vulnerable to severe zoonotic disease.

Owners are encouraged to adopt adult cats (>1 year old), maintain an indoor-only lifestyle, and follow proper wound care and hygiene practices to minimize zoonotic risk.

Integration of Veterinary Diagnostics: Bioguard Solutions

Accurate and timely diagnosis is crucial for effective management of B. henselae infections. Bioguard’s rapid diagnostic platforms, including the miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer and Qmini Nucleic Acid Extractor & Real-Time PCR Analyzer, allow veterinarians to detect Bartonella infections efficiently, even when bacterial loads are low or intermittent. By combining high sensitivity molecular testing with reliable susceptibility profiling, these tools support evidence-based clinical decision-making, helping to protect feline patients and reduce zoonotic risk for humans.

Continued Relevance in Veterinary and Zoonotic Medicine

Bartonella spp. exemplify the One Health paradigm, bridging feline medicine, vector ecology, and human public health. In veterinary practice, infection is increasingly associated with sporadic but serious inflammatory and immune-mediated disorders, including endocarditis, myocarditis, and uveitis. In humans, B. henselae is the causative agent of Cat Scratch Disease and can trigger life-threatening vasoproliferative disorders in immunocompromised individuals. Veterinary personnel face recognized occupational risks, necessitating heightened awareness, rigorous hygiene, and preventive protocols in clinical settings.

To visualize clinical management, consider B. henselae as a “leaky pipe in a complex plumbing system.” Complete replacement of the system (bacterial eradication) is often impractical, but maintaining effective sealants (vector control) and protecting the most valuable areas (high-risk individuals) remains the most efficient and sustainable approach to minimizing damage and preserving overall health. Bioguard’s diagnostic tools act as precision instruments for identifying leaks and guiding targeted interventions, ensuring optimal patient care while supporting One Health objectives.

The miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer, a tool designed to help combat antimicrobial resistance with game-changing features:

Feature | Benefit |

Fast Results | Get results in just 6 hours, enabling swift and confident treatment. |

Automated Interpretations | Instantly deliver precise susceptibility profiles, supporting faster, more informed clinical decisions and optimizing patient care. |

Dual-Sample Testing | Double the efficiency with simultaneous analysis of two samples at once. |

High Accuracy | Achieve an impressive 92% accuracy rate compared to traditional disc diffusion tests. |

📌 Note for Veterinarians:

The miniAST Veterinary Antibiotic Susceptibility Test Analyzer is available exclusively to licensed veterinarians and veterinary hospitals.

📩 How to Order MiniAST

To purchase MiniAST or request a quotation, please contact our sales team or email our customer service:

📧 service@bioguardlabs.com

☎️ Please include your hospital name and contact number so our sales representative can follow up with you directly.

LeBoit PE. Bacillary angiomatosis. In Connor DH, Chandler FW, Manz HJ, et al. (eds.), Pathology of infectious diseases. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1997: 239–252.

Chomel BB, Gurfield AN, Boulouis HJ, Kasten RW and Piemont Y. Réservoir félin de l’agent de la maladie des griffes du chat, Bartonella henselae, en région parisienne: resultants préliminaires. Rec Med Vet 1995; 171: 841–845.

KAPLAN, A. J., BENSON, C., HOLMES, K. K., BROOKS, J. T., PAU, A. & MASUR, H. (2009) Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 58, 1-198.

Belgard, S., U. Truyen, J. C. Thibault, C. Sauter-Louis and K. Hartmann (2010). “Relevance of feline calicivirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, feline herpesvirus and Bartonella henselae in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis.” Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 123(9-10): 369-376.

Bennett, A. D., D. A. Gunn-Moore, M. Brewer and M. R. Lappin (2011). “Prevalence of Bartonella species, haemoplasmas and Toxoplasma gondii in cats in Scotland.” J Feline Med Surg 13(8): 553-557.

Biancardi, A. L. and A. L. L. Curi (2014). “Cat-Scratch Disease.” Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 22(2): 148-154.

Chomel, B. B., R. W. Kasten, K. Floyd-Hawkins, B. Chi, K. Yamamoto, J. Roberts-Wilson, A. N. Gurfield, R. C. Abbott, N. C. Pedersen and J. E. Koehler (1996). “Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea.” J Clin Microbiol 34(8): 1952-1956.

Chomel, B. B., R. W. Kasten, C. Williams, A. C. Wey, J. B. Henn, R. Maggi, S. Carrasco, J. Mazet, H. J. Boulouis, R. Maillard and E. B. Breitschwerdt (2009). “Bartonella endocarditis: a pathology shared by animal reservoirs and patients.” Ann N Y Acad Sci 1166: 120-126.

Chomel, B. B., A. C. Wey, R. W. Kasten, B. A. Stacy and P. Labelle (2003). “Fatal case of endocarditis associated with Bartonella henselae type I infection in a domestic cat.” J Clin Microbiol 41(11): 5337-5339.

Cunningham, E. T. and J. E. Koehler (2000). “Ocular bartonellosis.” Am J Ophthalmol 130(3): 340-349.

Dowers, K. L., J. R. Hawley, M. M. Brewer, A. K. Morris, S. V. Radecki and M. R. Lappin (2010). “Association of Bartonella species, feline calicivirus, and feline herpesvirus 1 infection with gingivostomatitis in cats.” J Feline Med Surg 12(4): 314-321.

Fabbi, M., L. De Giuli, M. Tranquillo, R. Bragoni, M. Casiraghi and C. Genchi (2004). “Prevalence of Bartonella henselae in Italian stray cats: evaluation of serology to assess the risk of transmission of Bartonella to humans.” J Clin Microbiol 42(1): 264-268.

Finkelstein, J. L., T. P. Brown, K. L. O’Reilly, J. Wedincamp, Jr. and L. D. Foil (2002). “Studies on the growth of Bartonella henselae in the cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae).” J Med Entomol 39(6): 915-919.

Glaus, T., R. Hofmann-Lehmann, C. Greene, B. Glaus, C. Wolfensberger and H. Lutz (1997). “Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae infection and correlation with disease status in cats in Switzerland.” Journal of clinical microbiology 35(11): 2883-2885.

Greene, C. E., M. McDermott, P. H. Jameson, C. L. Atkins and A. M. Marks (1996). “Bartonella henselae infection in cats: evaluation during primary infection, treatment, and rechallenge infection.” Journal of clinical microbiology 34(7): 1682-1685.

Guptill, L. (2012). “Bartonella infections in cats: what is the significance?” In Practice 34(8): 434.

Guptill, L., L. Slater, C. C. Wu, T. L. Lin, L. T. Glickman, D. F. Welch and H. HogenEsch (1997). “Experimental infection of young specific pathogen-free cats with Bartonella henselae.” J Infect Dis 176(1): 206-216.

Gurfield, A. N., H. J. Boulouis, B. B. Chomel, R. W. Kasten, R. Heller, C. Bouillin, C. Gandoin, D. Thibault, C. C. Chang, F. Barrat and Y. Piemont (2001). “Epidemiology of Bartonella infection in domestic cats in France.” Vet Microbiol 80(2): 185-198.

Kamrani, A., V. R. Parreira, J. Greenwood and J. F. Prescott (2008). “The prevalence of Bartonella, hemoplasma, and Rickettsia felis infections in domestic cats and in cat fleas in Ontario.” Canadian journal of veterinary research = Revue canadienne de recherche veterinaire 72(5): 411-419.

Klotz, S. A., V. Ianas and S. P. Elliott (2011). “Cat-scratch Disease.” Am Fam Physician 83(2): 152-155.

Kordick, D. L. and E. B. Breitschwerdt (1997). “Relapsing bacteremia after blood transmission of Bartonella henselae to cats.” Am J Vet Res 58(5): 492-497.

Kordick, D. L., T. T. Brown, K. Shin and E. B. Breitschwerdt (1999). “Clinical and pathologic evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats.” Journal of clinical microbiology 37(5): 1536-1547.

Lucey, D., M. J. Dolan, C. W. Moss, M. Garcia, D. G. Hollis, S. Wegner, G. Morgan, R. Almeida, D. Leong, K. S. Greisen and et al. (1992). “Relapsing illness due to Rochalimaea henselae in immunocompetent hosts: implication for therapy and new epidemiological associations.” Clin Infect Dis 14(3): 683-688.

Namekata, D. Y., R. W. Kasten, D. A. Boman, M. H. Straub, L. Siperstein-Cook, K. Couvelaire and B. B. Chomel (2010). “Oral shedding of Bartonella in cats: correlation with bacteremia and seropositivity.” Veterinary microbiology 146(3-4): 371-375.

Pennisi, M. G., E. La Camera, L. Giacobbe, B. M. Orlandella, V. Lentini, S. Zummo and M. T. Fera (2009). “Molecular detection of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae in clinical samples of pet cats from Southern Italy.” Research in veterinary science 88: 379-384.

Pennisi, M. G., F. Marsilio, K. Hartmann, A. Lloret, D. Addie, S. Belák, C. Boucraut-Baralon, H. Egberink, T. Frymus, T. Gruffydd-Jones, M. J. Hosie, H. Lutz, K. Möstl, A. D. Radford, E. Thiry, U. Truyen and M. C. Horzinek (2013). “Bartonella Species Infection in Cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management.” Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 15(7): 563-569.

Quimby, J. M., T. Elston, J. Hawley, M. Brewer, A. Miller and M. R. Lappin (2008). “Evaluation of the association of Bartonella species, feline herpesvirus 1, feline calicivirus, feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus with chronic feline gingivostomatitis.” J Feline Med Surg 10(1): 66-72.

Regnery, R. L., J. A. Rooney, A. M. Johnson, S. L. Nesby, P. Manzewitsch, K. Beaver and J. G. Olson (1996). “Experimentally induced Bartonella henselae infections followed by challenge exposure and antimicrobial therapy in cats.” Am J Vet Res 57(12): 1714-1719.

Stützer, B. and K. Hartmann (2012). “Chronic Bartonellosis in Cats: What are the potential implications?” Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 14(9): 612-621.

Ueno, H., T. Hohdatsu, Y. Muramatsu, H. Koyama and C. Morita (1996). “Does coinfection of Bartonella henselae and FIV induce clinical disorders in cats?” Microbiol Immunol 40(9): 617-620.

Valasek, M. A. and J. J. Repa (2005). “The power of real-time PCR.” Adv Physiol Educ 29(3): 151-159.

Whittemore, J. C., J. R. Hawley, S. V. Radecki, J. D. Steinberg and M. R. Lappin (2012). “Bartonella species antibodies and hyperglobulinemia in privately owned cats.” Journal of veterinary internal medicine 26(3): 639-644.

Zangwill, K. M. (2013). Cat Scratch Disease and Other Bartonella Infections. Hot Topics in Infection and Immunity in Children IX. N. Curtis, A. Finn and A. J. Pollard. New York, NY, Springer New York: 159-166.