Table of Contents

1. Introduction: Feline Calicivirus in Veterinary Practice

1.1 Background

Feline Calicivirus (FCV) remains one of the most clinically significant viral pathogens affecting domestic cats, particularly as a leading cause of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Its impact is amplified by the virus’s intrinsic biological properties: FCV exhibits high genetic variability, a remarkable ability to persist in chronically infected carriers, and environmental stability that enables sustained circulation within shelters, colonies, and multi-cat households. These features contribute not only to recurrent outbreaks but also to efficient viral maintenance within feline populations worldwide.

From a virological standpoint, FCV is a small, non-enveloped, icosahedral virus, measuring approximately 30–40 nm in diameter and harboring a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of roughly 7.7 kb. Its use of junctional adhesion molecule-1 (JAM-1) as a cellular receptor facilitates viral entry and dissemination. Infection typically begins following exposure through the nasal, oral, or conjunctival routes, with the oropharynx serving as the primary site of replication. Viral amplification here drives epithelial necrosis, leading to the characteristic oral ulcerations most commonly identified along the margins of the tongue.

Given the combination of widespread prevalence, substantial morbidity, and occasional highly virulent systemic outbreaks, a consolidated review of FCV’s structure, replication biology, epidemiology and clinical behavior remains essential for contemporary veterinary practice.

1.2 Objectives

This article aims to synthesize current evidence from molecular virology, clinical epidemiology and field management to guide veterinary professionals, shelter medicine practitioners and cattery managers.

- Summarize evidence-based findings on FCV structure, replication and pathogenesis.

A molecular understanding of FCV underpins rational approaches to diagnosis, prevention and therapeutic intervention. Particular focus is placed on capsid architecture, genomic organization, antigenic variability and the early host–virus interactions that shape clinical outcomes. - Provide veterinarians and cattery managers with practical prevention and care strategies.

In high-density environments, controlling FCV transmission requires a layered approach that combines:

• vaccination programs,

• minimizing population stress and overcrowding,

• rigorous hygiene and environmental disinfection, and

• timely clinical management of affected cats.

Although vaccination remains central to disease mitigation, it typically does not prevent infection or viral shedding, and breakthrough infections continue to occur. Effective clinical management therefore relies heavily on supportive measures such as intravenous fluid therapy for dehydration, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pyrexia and oral pain, and targeted antibiotics for secondary bacterial complications.

- Highlight key clinical risks, including oral ulceration, FCV-associated lameness and virulent systemic disease (VSD).

- Oral Ulceration:

A hallmark of classical FCV infection, especially in kittens, appearing after an incubation period of 2–10 days. It is frequently accompanied by sneezing and serous nasal discharge. - FCV-Associated Lameness:

Characterized by acute synovitis with joint effusion and synovial membrane thickening. This syndrome may arise days to weeks after respiratory signs or following vaccination.

• Virulent Systemic Disease (VSD):

A rare, highly pathogenic phenotype with reported mortality rates up to 67 percent. VSD is marked by systemic inflammatory response syndrome, disseminated coagulopathy and multi-organ failure. Clinically, affected cats exhibit severe URTI signs followed by cutaneous ulcerations, alopecia of the extremities, broncho-interstitial pneumonia and necrosis of major organs including the liver, spleen and pancreas. Management requires intensive supportive care, often incorporating corticosteroids and interferon.

2. Viral Structure and Molecular Biology

Feline Calicivirus (FCV) belongs to the Caliciviridae family, a group of small, non-enveloped RNA viruses characterized by compact genomes and efficient replication strategies. The structural and molecular features of FCV underpin its clinical behavior, including its ability to persist, diversify, and evade immune surveillance in feline populations.

2.1 Virion Architecture

FCV is a non-enveloped, icosahedral virus measuring 30–40 nm in diameter. Its capsid is considered “naked”, reflecting the absence of a lipid envelope. The virion is composed of a single capsid protein, with a precursor mass of 65–66 kDa, which is later processed into the major structural protein VP1. This protein forms the characteristic icosahedral shell that encases the viral RNA genome.

2.2 Genome Organization

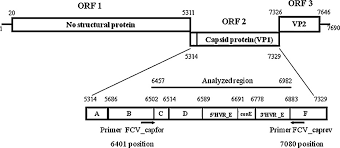

The genome of FCV consists of a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA molecule of approximately 7.7 kb, organized into three Open Reading Frames (ORFs):

ORF1 – Non-structural Polyprotein

- Encodes a 200 kDa polyprotein that undergoes proteolytic cleavage to produce six mature non-structural proteins, essential for RNA replication and virion assembly.

ORF2 – Capsid Precursor (preVP1)

- Encodes a 73 kDa capsid precursor (preVP1).

• Undergoes rapid cleavage during maturation to yield the 60 kDa VP1 capsid protein.

• Subdivided into regions A–F; among these, the E-region determines antigenicity and contributes to formation of the P2 subdomain, a key external protrusion involved in receptor interaction and immune recognition.

ORF3 – Minor Structural Protein VP2

- Encodes VP2, a 12 kDa protein (106 amino acids) that, although less abundant, is essential for producing infectious virions and supports VP1 stability during assembly.

2.3 Replication Cycle

FCV replication proceeds through the synthesis of:

- A 7.7 kb genomic RNA (positive-sense)

• A 2.4 kb subgenomic RNA, which serves as the template for capsid protein translation

Viral entry is mediated by junctional adhesion molecule-1 (JAM-1), identified as the functional receptor during in vitro studies. Once inside the host cell, FCV induces a characteristic cytopathic effect (CPE)—notably cell rounding and membrane blebbing.

A central mechanism of viral dominance is the shut-off of host protein synthesis, accomplished through cleavage of eIF4G, a critical eukaryotic initiation factor. This redirection enables preferential translation of viral RNA and efficient progeny production.

3. Epidemiology

3.1 Global Distribution

Feline Calicivirus (FCV) was first isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of cats in New Zealand (Fastier, 1957). Since that initial discovery, FCV has been recognized as a globally widespread pathogen, circulating in domestic and free-roaming feline populations across continents. Its prevalence is particularly high in high-density environments, such as multi-cat households, shelters, and breeding colonies. Studies consistently report 25–40 percent infection rates among cats in colonies and shelters (Wardley et al. 1974, Bannasch & Foley 2005).

The combination of environmental persistence, antigenic diversity, and efficient cat-to-cat transmission ensures FCV remains an endemic viral pathogen in most feline communities worldwide.

3.2 Transmission and Persistence

FCV transmission occurs predominantly through oral, nasal, or conjunctival exposure. Direct contact with secretions, as well as indirect exposure through contaminated fomites, facilitates rapid spread—particularly in environments where sanitation and isolation practices are difficult to maintain.

Several biological features of FCV contribute to its sustained circulation:

Key factors promoting persistence:

- High genetic variability, enabling viral immune evasion and emergence of antigenic variants.

- Exceptional environmental stability, allowing survival on surfaces and equipment.

- Existence of long-term carriers, where cats may shed infectious virus for 30 days to several years post-recovery (Wardley, 1976).

- Sequential infections and reinfections, driven by antigenic divergence among circulating strains (Coyne et al. 2007).

These characteristics underscore the challenges faced by shelters and catteries in controlling FCV outbreaks, especially when population turnover is high.

3.3 Zoonotic Potential

Despite its widespread presence in cats, Feline Calicivirus is not considered zoonotic. There is no evidence indicating that humans are susceptible to FCV infection (Radford et al. 2009). Thus, the implications of FCV remain confined to feline health and management rather than public health.

FCV Prevalence Data Across Cat Populations

Setting | Reported Prevalence | Supporting Sources |

Shelters and Colonies | 25–40 percent | Wardley et al. 1974; Bannasch & Foley 2005; Helps et al. 2005 |

General Feline Populations | Ubiquitous worldwide | Radford et al. 2009; Pesavento et al. 2008 |

Long-Term Carrier Prevalence | Shedding for 30 days to years | Wardley 1976; Coyne et al. 2007 |

4. Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Feline Calicivirus (FCV) reflects a sequence of early mucosal infection, systemic dissemination and localized tissue injury, culminating in the characteristic lesions seen in clinical disease. The severity of this process varies markedly between classical FCV infections and the rare but highly pathogenic virulent systemic disease (VSD) phenotype.

4.1 Initial Infection

FCV typically enters the host through the nasal, oral or conjunctival routes, exploiting direct contact with respiratory or oral secretions. Following entry, the oropharynx acts as the primary site of viral replication, supporting robust amplification of the virus within epithelial tissues.

By 3 to 4 days post-infection, FCV induces a transient viraemia, permitting dissemination to multiple organ systems. During this phase, viral RNA and antigen can be detected in a variety of tissues beyond the upper respiratory tract. This early systemic spread sets the stage for both localized mucosal lesions and, in rare cases, the extensive tissue involvement seen in virulent systemic FCV infections.

4.2 Mechanisms of Tissue Injury

FCV-induced tissue injury results from a combination of direct viral cytopathic effects and the host inflammatory response:

- Epithelial necrosis and ulceration:

Viral replication within epithelial cells causes cellular degeneration and vesicle formation, which subsequently evolve into ulcers, most commonly observed at the margins of the tongue. These oral lesions represent one of the most distinctive clinical manifestations of classic FCV infection. - Neutrophilic inflammation:

In both dermal and mucosal tissues, FCV infection triggers neutrophilic infiltration, contributing to local inflammation and discomfort. This inflammatory response amplifies epithelial damage and supports the progression of mucosal lesions. - Healing and recovery:

Tissue repair generally commences 2 to 3 weeks after infection, corresponding with resolution of viraemia and reduction in viral load.

While these mechanisms underlie the common clinical signs—oral ulceration, sneezing and serous nasal discharge—more severe disease can develop when the virus exhibits heightened virulence. In cases of virulent systemic FCV disease (VSD), viral replication extends into tissues not typically involved in classical FCV infection. This results in widespread ulcerative lesions, systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multi-organ failure, making VSD a high-mortality clinical emergency.

5. Clinical Manifestations

Feline Calicivirus (FCV) produces a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from mild upper respiratory disease to fulminant systemic illness. The diversity of manifestations reflects both viral virulence and host factors such as age, immune status and concurrent infections.

5.1 Oral and Upper Respiratory Tract Disease

Following an incubation period of 2–10 days, classical FCV infection most commonly produces oral and upper respiratory signs, particularly in young kittens, whose immune systems are still developing.

Typical Clinical Signs

- Oral ulceration, especially along the margins of the tongue, resulting from vesicle rupture and epithelial necrosis.

- Sneezing and serous nasal discharge, reflecting inflammation of the nasal mucosa and upper airways.

Severe Presentations

Although many infections remain mild, some cats—especially very young or immunocompromised individuals—may develop:

- Pneumonia

- Dyspnea

- Pyrexia

- Depression and lethargy

These severe presentations correlate with higher viral loads and more extensive epithelial injury.

5.2 FCV-Associated Lameness (Limping Syndrome)

A distinct clinical entity known as limping syndrome can accompany or follow FCV infection. This condition is believed to arise from virus-induced immune-mediated synovitis.

Key Features

- Acute synovitis involving one or multiple joints

- Synovial membrane thickening

- Increased synovial fluid volume

- Intermittent lameness that may shift between limbs

Fever often precedes or accompanies the onset of lameness. This syndrome can also occur post-vaccination, reflecting immune stimulation by vaccine strains in susceptible cats.

5.3 Virulent Systemic Disease (VSD)

Virulent systemic FCV disease (VSD) represents a rare, highly pathogenic phenotype with mortality rates reaching up to 67 percent. VSD is characterized by uncontrolled viral replication, widespread vascular injury and severe systemic inflammatory response.

Systemic Pathological Features

- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Multi-organ failure, frequently fatal

Widespread Lesions

FCV in VSD infiltrates tissues not typically affected in classical infection, leading to:

- Ulceration of the skin

- Alopecia affecting the nose, lips, ears, periocular regions and footpads

- Broncho-interstitial pneumonia

- Necrosis of vital organs, including the liver, spleen and pancreas

Clinically, VSD often begins as a severe upper respiratory tract illness before rapidly progressing to systemic compromise.

5.4 Molecular Pathogenesis

At the cellular level, FCV induces a sequence of molecular events that drive tissue destruction and clinical disease:

- Cytopathic effects (CPE), including cell rounding and membrane blebbing, reflect direct viral injury.

- Shut-down of host protein synthesis occurs via the cleavage of eIF4G, redirecting translational machinery toward viral RNA.

- JAM-1 (junctional adhesion molecule-1) serves as the functional receptor, mediating viral entry and influencing tissue tropism.

These processes operate synergistically to determine lesion distribution, severity and systemic involvement.

6. Diagnosis (Feline Calicivirus)

Diagnosis of Feline Calicivirus (FCV) infection relies on a combination of molecular, virological and serological techniques, each providing complementary information regarding viral presence, replication status and host immunity. Given the substantial genetic variability of FCV, diagnostic tools must be selected and interpreted with care.

6.1 Molecular Methods

Molecular diagnostics represent the most sensitive and specific approach for detecting FCV infection.

- RT-PCR assays—including conventional, nested and real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR—are widely used to detect viral RNA.

- Suitable clinical samples include conjunctival and oral swabs, blood, skin scrapings and lung tissue (particularly in systemic disease or necropsy cases).

- RT-PCR offers the advantage of detecting low viral loads and enabling strain differentiation, which is valuable for outbreak investigation and epidemiological studies.

Because FCV exhibits marked genetic diversity, molecular assays must be validated against a broad panel of viral strains. Without such validation, sequence variability may produce false-negative results, particularly in hypervariable regions of the genome.

6.2 Virus Isolation

Virus isolation remains an important tool for confirming active FCV replication, although it is more labor-intensive than molecular approaches.

- Infectious virus can be isolated from nasal, conjunctival and oropharyngeal swabs.

- Unlike PCR, isolation is generally less affected by strain variation, as it depends on viral replication rather than sequence matching.

However, successful isolation requires samples with sufficient viable virus. Isolation may fail when:

- Viral titers are low,

- Virus undergoes inactivation during sample transport, or

- Antibodies present in the sample inhibit infectivity.

As a result, virus isolation is often reserved for specialized laboratories or confirmatory testing.

6.3 Serology

Serological assays evaluate the host’s immune response rather than detecting the virus directly.

- ELISA tests can identify the presence of anti-FCV antibodies, but interpretation is challenging because seroprevalence is high in cats due to natural infection and vaccination.

- Virus neutralization assays (VNA) measure functional neutralizing antibody titers and may help determine whether a cat possesses protective immunity.

Serology is most useful for population surveillance or assessing vaccination response, rather than diagnosing acute infection.

7. Vaccination

Vaccination represents a cornerstone of FCV prevention and remains one of the most effective tools for reducing the clinical burden of disease in feline populations. However, immunization outcomes are strongly influenced by the substantial antigenic diversity of circulating FCV strains and the biological limitations inherent to currently available vaccines.

7.1 Available Vaccine Types

Commercial FCV vaccines are based on whole viral antigens propagated in cell culture, formulated to stimulate protective immunity against acute clinical disease. Several types are available:

- Monovalent vaccines targeting a single FCV strain

- Bivalent vaccines incorporating two viral strains to broaden antigenic coverage

- Live-attenuated vaccines, providing robust mucosal immunity but generally contraindicated in certain immunocompromised populations

- Inactivated vaccines, produced in adjuvanted or non-adjuvanted forms, offering improved safety profiles for specific clinical contexts

These formulations are often included as components of multivalent feline core vaccines, paired with agents such as feline herpesvirus and panleukopenia virus.

7.2 Recommended Protocol

Immunization schedules are designed to ensure adequate priming of the immature immune system in kittens, followed by maintenance of immunity into adulthood.

- Primary vaccination: Administered at 8–9 weeks and 12 weeks of age

- Booster doses: Given annually thereafter, although some guidelines allow risk-based extension of intervals in low-exposure adult cats

These schedules help mitigate early-life susceptibility and support sustained population immunity in high-density settings.

7.3 Limitations

Despite their clinical usefulness, FCV vaccines have well-recognized limitations:

Incomplete prevention of infection and shedding

While vaccination significantly reduces the severity of oral and upper respiratory disease, it does not reliably prevent infection nor eliminate viral shedding. Vaccinated cats may still act as carriers, contributing to transmission dynamics.

Antigenic diversity and strain mismatch

The extensive genetic and antigenic heterogeneity of FCV remains a major challenge. No existing vaccine offers comprehensive protection against all circulating strains, and breakthrough infections are occasionally observed, particularly during outbreaks involving divergent or virulent strains.

Uncertain safety in pregnant queens

Safety data for FCV vaccination in pregnant queens are limited. Although vaccinating queens prepartum may enhance maternally derived antibodies (MDA) and improve protection in kittens, routine use during pregnancy is not universally recommended due to insufficient evidence.

Practical Considerations in Multi-Cat Environments

In high-density settings such as boarding facilities, shelters and breeding catteries, vaccination must be integrated into a broader infection-control framework:

- Avoiding overcrowding

- Implementing strict hygiene and disinfection protocols

- Minimizing stress and maintaining optimal husbandry

- Ensuring rapid isolation of symptomatic individuals

These measures are essential complements to vaccination, helping reduce viral load, prevent outbreaks and protect vulnerable populations.

8. Disease Management and Treatment

Effective treatment of Feline Calicivirus (FCV) hinges on timely supportive care, targeted management of secondary complications and rigorous environmental control—particularly in multi-cat populations where viral transmission is amplified. In the case of virulent systemic FCV disease (VSD), intervention must escalate rapidly, as the syndrome progresses with high morbidity and mortality.

8.1 Supportive Care

Supportive therapy remains the foundation of FCV management, especially during acute oral and respiratory disease.

Hydration and Electrolyte Stabilization

- Intravenous fluid therapy is essential in cats with dehydration, electrolyte imbalance or acid–base disturbances.

- Restoring fluid status is particularly important for cats experiencing anorexia, fever or oral ulcerations that impair normal drinking behavior.

Pain and Fever Control

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be administered to reduce pyrexia and oral pain, thereby improving comfort and supporting voluntary food intake.

Nutritional Support

- Inappetence is common due to oral ulceration. Blended or softened diets may be required.

- If voluntary intake does not resume within three days, enteral feeding via a feeding tube is indicated to prevent hepatic lipidosis and support immune function.

These interventions collectively address the metabolic stress associated with FCV infection and accelerate recovery.

8.2 Antimicrobial Therapy

Although FCV is a viral pathogen, secondary bacterial infections may arise due to mucosal damage.

- Antibiotic therapy is recommended in cases of severe respiratory involvement, pyrexia or suspicion of bacterial superinfection.

- Agents should be selected based on their penetration into respiratory tissues and oral mucosa.

Antibiotics do not treat FCV itself but help mitigate complications that may otherwise prolong clinical illness.

8.3 Environmental and Population Management

In multi-cat environments—including shelters, boarding facilities and breeding catteries—successful FCV control requires coordinated population-level strategies.

Key Control Measures

- Vaccination: While effective in reducing disease severity, FCV vaccines do not prevent infection or viral shedding, and must be paired with other interventions.

- Avoiding overcrowding: Reduces stress and transmission.

- Strict hygiene and husbandry: Regular cleaning of feeding stations, bedding, litter boxes and commonly touched surfaces.

- Disinfection: Necessary because FCV is shed in respiratory secretions, saliva, skin lesions, urine and feces. Its environmental stability means that contaminated fomites can contribute significantly to transmission.

Comprehensive environmental management reduces viral load, limits outbreaks and protects vulnerable populations such as kittens and immunocompromised cats.

8.4 Management of Virulent Systemic Disease (VSD)

Virulent systemic disease represents the most severe form of FCV infection and requires immediate, aggressive intervention.

Intensive Supportive Therapy

- Fluid therapy to stabilize perfusion and counteract systemic inflammatory response.

- Broad-spectrum antimicrobials to manage secondary infections.

- Corticosteroids may be used in select critical cases to modulate inflammation.

- Interferon therapy has been employed as an immunomodulatory support.

Antiviral Considerations

- Ribavirin has demonstrated in vitro inhibition of FCV replication, but clinical application is constrained by toxicity and adverse effects.

- No safe, effective antiviral therapy for FCV is currently available for routine clinical use.

VSD demands rigorous monitoring, as rapid clinical deterioration is common despite treatment.

9. Care Guidelines for Cat Owners and Shelters

Effective control of Feline Calicivirus (FCV) depends on a comprehensive, multifactorial strategy that integrates vaccination, environmental hygiene and the careful management of cat populations. These measures are especially important in high-density environments such as shelters, boarding facilities and breeding catteries, where FCV transmission is amplified by close contact and shared fomites.

9.1 Key Preventive Measures

Vaccination Compliance

Routine vaccination remains the cornerstone of FCV prevention.

- Kittens should receive a primary course at 8–9 weeks and again at 12 weeks, followed by annual boosters.

- Although vaccination offers good protection against acute oral and upper respiratory disease, it does not prevent infection or viral shedding. Vaccinated cats may therefore still contribute to environmental contamination and transmission.

Minimizing Stress and Overcrowding

Environmental stressors—particularly overcrowding—significantly increase susceptibility to FCV infection and enhance viral spread.

- Shelters and catteries should limit population density, maintain stable social groupings and implement stress-reduction strategies to reduce viral load and transmission risk.

Regular Sanitation Protocols

Rigorous hygiene and husbandry practices are essential.

- FCV is shed via respiratory secretions, oral secretions, and skin lesions, and has also been isolated from faeces and urine, underscoring the need for thorough disinfection.

- High-contact surfaces, feeding stations, bedding, litter boxes and transport carriers must be cleaned frequently using disinfectants known to inactivate non-enveloped viruses.

Isolation of Symptomatic or Newly Arrived Cats

Because FCV spreads readily through direct contact and fomites:

- Symptomatic cats should be promptly isolated.

- Newly admitted cats should undergo a quarantine period before introduction to resident populations.

- Staff should follow minimum-handling protocols to limit cross-contamination.

9.2 Long-Term Considerations

Counseling Owners About Chronic Shedders

Owners should be educated about FCV’s capacity for persistent infection.

- Some cats become long-term shedders, releasing virus for 30 days to years after recovery, regardless of vaccination status.

- Understanding this chronic shedding potential is crucial for managing multi-cat households and planning introductions between cats.

Monitoring High-Risk Populations

Certain groups require more intensive observation and preventive strategies:

- Kittens, due to their naïve immune systems and the short incubation period of 2–10 days.

- Densely housed cats, where FCV prevalence can reach 25–40 percent, particularly in colonies and shelter environments.

Enhanced surveillance, early detection of clinical signs and consistent adherence to hygiene protocols are essential for managing these vulnerable populations.

10. Conclusion

Feline Calicivirus (FCV) remains a globally important feline pathogen, owing to its widespread prevalence and its frequent role in upper respiratory disorders. Its high genetic variability complicates immunity, and no currently available vaccine protects against all circulating field strains. Moreover, FCV can persist for months to years in recovered cats, sustaining virus circulation via chronic shedding. These features underline the need for a robust, evidence-based approach to FCV control.

Effective FCV management should include:

- Vaccination (primary course at 8–9 and 12 weeks, followed by annual boosters), which reduces disease severity though does not eliminate infection or shedding;

- Stringent hygiene, diligent cleaning and population management, especially in multi-cat environments, to minimize viral load and transmission;

- Rapid diagnostic capabilities to detect infection early, enable isolation, and guide outbreak management — a critical need in shelters, catteries, and veterinary clinics.

In this context, access to reliable in-house molecular tools is increasingly important for practitioners who need to detect and control Feline Calicivirus in real time.

Bioguard’s Qmini real-time PCR system offers a powerful and practical tool for FCV surveillance and control:

- The Qmini Real-Time PCR Analyzer delivers high sensitivity and specificity through optimized assays and TaqMan-based detection, making it capable of identifying FCV even when viral loads are low or samples are collected late.

- Its compact, space-saving design and streamlined workflow (with compatible nucleic acid extraction kits) make it feasible for veterinary clinics, shelters or catteries to run in-house molecular diagnostics without requiring large laboratory infrastructure.

- Because FCV is genetically diverse, a PCR system like Qmini—when paired with primers and probes validated across multiple strains—enables broad-spectrum detection and accurate discrimination among FCV variants, supporting molecular surveillance and early detection of emerging or virulent strains.

- The capacity for rapid turn-around allows veterinary teams to make timely decisions on isolation, treatment and outbreak containment — minimizing spread and improving animal welfare.

Source:

Hurley, K. F. (2006). Virulent calicivirus infection in cats. Proceedings of the 24th Annual American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum, May 31–June 3, 585.

Iglauer, F., Gartner, K., & Morstedt, R. (1989). Maternal protection against feline respiratory disease by means of booster vaccinations during pregnancy: A retrospective clinical study. Kleintierpraxis, 34, 235.

Gaskell, R., & Dawson, S. (1998). Feline respiratory disease. In C. E. Greene (Ed.), Infectious diseases of the dog and cat (pp. 97–106). WB Saunders Company.

Knowles, J. O. (1988). Studies on feline calicivirus with particular reference to chronic stomatitis in the cat (Doctoral dissertation). University of Liverpool.

Pedersen, N. C., Laliberte, L., & Ekman, S. (1983). A transient febrile “limping” syndrome of kittens caused by two different strains of feline calicivirus. Feline Practice, 13, 26–35.

Gaskell, R. M., Dawson, S., & Radford, A. D. (2006). Feline respiratory disease. In C. E. Greene (Ed.), Infectious diseases of the dog and cat (pp. 145–154). Saunders Elsevier.

Gaskell, R. M. (1985). Viral-induced upper respiratory tract diseases. In E. A. Chandler, C. J. Gaskell, & A. D. R. Hilbery (Eds.), Feline medicine and therapeutics (pp. 257–270). Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Carter, M. J., & Madeley, C. R. (1987). Caliciviridae. In M. V. Nennut & A. C. Steven (Eds.), Animal virus structure (pp. 99, 121–128). Elsevier.

Abd-Eldaim, M., Potgieter, L., & Kennedy, M. (2005). Genetic analysis of feline caliciviruses associated with a hemorrhagic-like disease. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 17(5), 420–429.

Bannasch, M. J., & Foley, J. E. (2005). Epidemiologic evaluation of multiple respiratory pathogens in cats in animal shelters. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 7(2), 109–119.

Carter, M. J. (1989). Feline calicivirus protein synthesis investigated by Western blotting. Archives of Virology, 108(1–2), 69–79.

Carter, M. J., Milton, I. D., Meanger, J., Bennett, M., Gaskell, R. M., & Turner, P. C. (1992). The complete nucleotide sequence of a feline calicivirus. Virology, 190(1), 443–448.

Carter, M. J., Milton, I. D., Turner, P. C., Meanger, J., Bennett, M., & Gaskell, R. M. (1992). Identification and sequence determination of the capsid protein gene of feline calicivirus. Archives of Virology, 122(3–4), 223–235.

Chen, R., Neill, J. D., Estes, M. K., & Prasad, B. V. V. (2006). X-ray structure of a native calicivirus: Structural insights into antigenic diversity and host specificity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(21), 8048–8053.

Coyne, K. P., Gaskell, R. M., Dawson, S., Porter, C. J., & Radford, A. D. (2007). Evolutionary mechanisms of persistence and diversification of a calicivirus within endemically infected natural host populations. Journal of Virology, 81(4), 1961–1971.

Dawson, S., Bennett, D., Carter, S. D., Bennett, M., Meanger, J., Turner, P. C., Milton, I., & Gaskell, R. M. (1994). Acute arthritis of cats associated with feline calicivirus infection. Research in Veterinary Science, 56(2), 133–143.

Di Martino, B., Marsilio, F., & Roy, P. (2007). Assembly of feline calicivirus-like particles and their immunogenicity. Veterinary Microbiology, 120(1), 173–178.

Fastier, L. B. (1957). A new feline virus isolated in tissue culture. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 18(67), 382–389.

Foley, J., Hurley, K., Pesavento, P. A., Poland, A., & Pedersen, N. C. (2006). Virulent systemic feline calicivirus infection: Local cytokine modulation and contribution of viral mutants. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 8(1), 55–61.

Guiver, M., Littler, E., Caul, E. O., & Fox, A. J. (1992). The cloning, sequencing and expression of a major antigenic region from the feline calicivirus capsid protein. Journal of General Virology, 73(9), 2429–2433.

Helps, C. R., Lait, P., Damhuis, A., Björnehammar, U., Bolta, D., Brovida, C., Chabanne, L., Egberink, H., Ferrand, G., Fontbonne, A., Pennisi, M. G., Gruffydd-Jones, T., Gunn-Moore, D., Hartmann, K., Lutz, H., Malandain, E., Möstl, K., Stengel, C., Harbour, D. A., & Graat, E. A. (2005). Factors associated with upper respiratory tract disease caused by feline herpesvirus, feline calicivirus, Chlamydophila felis and Bordetella bronchiseptica in cats: Experience from 218 European catteries. Veterinary Record, 156(21), 669–673.

Herbert, T. P., Brierley, I., & Brown, T. D. (1996). Detection of the ORF3 polypeptide of feline calicivirus in infected cells and evidence for its expression from a bicistronic subgenomic mRNA. Journal of General Virology, 77(1), 123–127.

Hurley, K. E., Pesavento, P. A., Pedersen, N. C., Poland, A. M., Wilson, E., & Foley, J. E. (2004). An outbreak of virulent systemic feline calicivirus disease. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 224(2), 241–249.

Makino, A., Shimojima, M., Miyazawa, T., Kato, K., Tohya, Y., & Akashi, H. (2006). Junctional adhesion molecule 1 is a functional receptor for feline calicivirus. Journal of Virology, 80(9), 4482–4490.

Milton, I. D., Turner, J., Teelan, A., Gaskell, R., Turner, P. C., & Carter, M. J. (1992). Location of monoclonal antibody binding sites in the capsid protein of feline calicivirus. Journal of General Virology, 73(9), 2435–2439.

Neill, J. D., Reardon, I. M., & Heinrikson, R. L. (1991). Nucleotide sequence and expression of the capsid protein gene of feline calicivirus. Journal of Virology, 65(10), 5440–5447.

Ossiboff, R. J., Zhou, Y., Lightfoot, P. J., Prasad, B. V. V., & Parker, J. S. (2010). Conformational changes in the capsid of a calicivirus upon interaction with its functional receptor. Journal of Virology, 84(11), 5550–5564.

Pedersen, N. C., Elliott, J. B., Glasgow, A., Poland, A., & Keel, K. (2000). An isolated epizootic of hemorrhagic-like fever in cats caused by a novel and highly virulent strain of feline calicivirus. Veterinary Microbiology, 73(4), 281–300.

Pesavento, P. A., Chang, K.-O., & Parker, J. S. L. (2008). Molecular virology of feline calicivirus. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 38(4), 775–786.

Pesavento, P. A., Maclachlan, N. J., Dillard-Telm, L., Grant, C. K., & Hurley, K. F. (2004). Pathologic, immunohistochemical and electron microscopic findings in naturally occurring virulent systemic feline calicivirus infection in cats. Veterinary Pathology, 41(3), 257–263.

Povey, R. C. (1978). Effect of orally administered ribavirin on experimental feline calicivirus infection in cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 39(8), 1337–1341.

Prikhodko, V. G., Sandoval-Jaime, C., Abente, E. J., Bok, K., Parra, G. I., Rogozin, I. B., Ostlund, E. N., Green, K. Y., & Sosnovtsev, S. V. (2014). Genetic characterization of feline calicivirus strains associated with varying disease manifestations during an outbreak season in Missouri (1995–1996). Virus Genes, 48(1), 96–110.

Radford, A. D., Addie, D., Belák, S., Boucraut-Baralon, C., Egberink, H., Frymus, T., Gruffydd-Jones, T., Hartmann, K., Hosie, M. J., Lloret, A., Lutz, H., Marsilio, F., Pennisi, M. G., Thiry, E., Truyen, U., & Horzinek, M. C. (2009). Feline calicivirus infection: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 11(7), 556–564.

Radford, A. D., Coyne, K. P., Dawson, S., Porter, C. J., & Gaskell, R. M. (2007). Feline calicivirus. Veterinary Research, 38(2), 319–335.

Seal, B. S., Ridpath, J. F., & Mengeling, W. L. (1993). Analysis of feline calicivirus capsid protein genes: Identification of variable antigenic determinant regions of the protein. Journal of General Virology, 74(11), 2519–2524.

Sosnovtsev, S. V., Belliot, G., Chang, K. O., Onwudiwe, O., & Green, K. Y. (2005). Feline calicivirus VP2 is essential for the production of infectious virions. Journal of Virology, 79(7), 4012–4024.

Sosnovtsev, S. V., & Green, K. Y. (2003). Feline calicivirus as a model for the study of calicivirus replication. Perspectives in Medical Virology, 9, 467–488.

Sosnovtsev, S. V., Sosnovtseva, S. A., & Green, K. Y. (1998). Cleavage of the feline calicivirus capsid precursor is mediated by a virus-encoded proteinase. Journal of Virology, 72(4), 3051–3059.

Southerden, P., & Gorrel, C. (2007). Treatment of a case of refractory feline chronic gingivostomatitis with feline recombinant interferon omega. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 48(2), 104–106.

Tohya, Y., Yokoyama, N., Maeda, K., Kawaguchi, Y., & Mikami, T. (1997). Mapping of antigenic sites involved in neutralization on the capsid protein of feline calicivirus. Journal of General Virology, 78(2), 303–305.

Wardley, R. C. (1976). Feline calicivirus carrier state: A study of the host/virus relationship. Archives of Virology, 52(3), 243–249.

Wardley, R. C., Gaskell, R. M., & Povey, R. C. (1974). Feline respiratory viruses: Their prevalence in clinically healthy cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 15(9), 579–586.

Willcocks, M. M., Carter, M. J., & Roberts, L. O. (2004). Cleavage of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4G and inhibition of host-cell protein synthesis during feline calicivirus infection. Journal of General Virology, 85(5), 1125–1130.