Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview of Feline Hyperthyroidism

Feline hyperthyroidism is the most common endocrine disorder affecting middle-aged and geriatric cats, driven overwhelmingly by autonomous thyroid adenomas or adenomatous hyperplasia. More than 97 percent of cases result from benign, functional proliferation of thyroid tissue that produces excessive amounts of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) (Peterson, 2013; Broussard et al., 1995).

The resulting hypermetabolic state manifests across multiple organ systems. Typical clinical signs include:

- Progressive weight loss, despite normal or increased appetite

- Polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria

- Episodic vomiting or diarrhea

- A dull or unkempt hair coat

- Tachycardia and a palpable thyroid nodule in many cases

These signs often begin subtly, then intensify as thyroid hormone excess accelerates metabolic turnover and causes secondary strain on cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal systems.

1.2 Limitations of Traditional Radioiodine (I-131) Dosing

Radioiodine (I-131) therapy is widely regarded as the treatment of choice for feline hyperthyroidism (Peterson, 2013; Mooney, 2001; Feldman & Nelson, 2015). I-131 concentrates selectively in hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, where emitted beta particles induce cytotoxicity and subsequent glandular fibrosis.

Traditional fixed-dose approaches, typically ranging from 3–5 mCi, have historically produced good cure rates Peterson, 2013; Williams et al., 2010; Peterson & Broome, 2015). However, these protocols are increasingly recognized as imprecise, with substantial rates of treatment-related complications:

- Iatrogenic Hypothyroidism (IH).

Fixed-dose regimens often exceed the minimal therapeutic requirement, exposing normal thyroid remnants to unnecessary radiation. Reported IH rates vary widely—from 30 to 80 percent—and represent a major concern in post-treatment management. - IH-associated azotemia carries significant prognostic implications. Cats that become hypothyroid and azotemic after treatment have significantly shorter survival times than cats that remain euthyroid or non-azotemic. This underscores the clinical importance of avoiding overtreatment.

1.3 Evidence Supporting Individualized Radioiodine Dosing

To mitigate these risks, Peterson and Rishniw (2021) developed a sophisticated, feline-specific dosing algorithm designed to deliver the lowest effective I-131 dose required to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing the likelihood of iatrogenic hypothyroidism and azotemia.

Drawing on data from 1,400 hyperthyroid cats, their study established several crucial findings:

- Median total dose: 1.9 mCi (range 1.0–10.6 mCi)

• Considerably lower than historical fixed-dose practices - Cure (euthyroid) rate: 74.8 percent, comparable to traditional outcomes

- Significantly lower complication rates:

• 4.1 percent overt hypothyroidism

• 17.1 percent subclinical hypothyroidism

• Combined rate (~21%) markedly lower than many fixed-dose protocols

These outcomes demonstrate that tailored dosing not only achieves therapeutic efficacy but also reduces the risk burden associated with excessive radiation exposure.

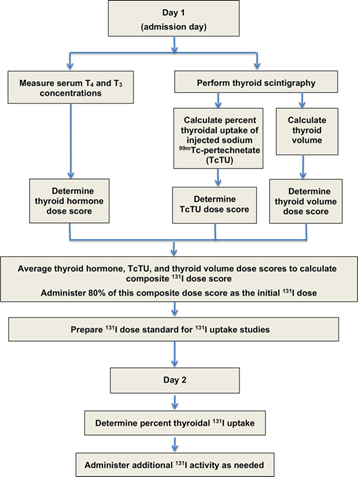

The Two-Day Algorithmic Protocol

The algorithm employs a structured, multiparametric approach based on objective measures of disease severity and biological iodine-handling capacity.

Day 1: Initial Composite Dose (80 percent administered)

A composite dose score is calculated by integrating three major disease indicators:

- Serum T4 and T3 concentrations

- Thyroid tumor volume, measured using thyroid scintigraphy

- Technetium uptake (TcTU), a marker of functional thyroid activity

Only 80 percent of this calculated composite dose is administered initially to avoid overtreatment.

Day 2: Uptake-Based Dose Adjustment

Approximately 24 hours later, the thyroidal I-131 uptake is measured to determine how effectively the gland concentrates radioiodine. A supplemental dose is then administered as needed.

In the study, 1,380 out of 1,400 cats required additional I-131 on Day 2, highlighting the essential role of uptake-based adjustment and the variability in individual glandular kinetics.

This two-step method mirrors the logic of precision dosing used in pharmaceutical sciences:

deliver enough activity to neutralize the hyperfunctioning tissue, but not so much that normal thyroid function is extinguished or renal sequelae are exacerbated.

2. Radioiodine Pharmacology

The therapeutic use of radioiodine (131I) in feline hyperthyroidism rests on a sophisticated interplay between thyroid physiology, nuclear physics, and disciplined radiation-safety practices. The following section synthesizes the core pharmacologic principles, uptake kinetics, veterinary dosimetry, and regulatory safety frameworks that underpin this therapy.

2.1 Mechanism of 131I

Radioiodine (131I) exploits the thyroid gland’s unique ability to concentrate iodine for hormone synthesis.

Targeting mechanism.

The follicular cells of the thyroid actively transport iodine from the bloodstream using the sodium–iodide symporter (NIS). Because the NIS cannot distinguish between stable iodine and 131I, hyperfunctional thyroid tissue accumulates radioiodine to levels that far exceed blood concentrations, often by a factor of 500-fold. In hyperthyroid cats, adenomatous tissue is especially efficient at concentrating 131I.

Destructive mechanism.

Once incorporated into the gland, 131I decays as a dual-emitter. Its therapeutic activity derives largely from the emission of high-energy beta (β–) particles, which:

- have a short path length (typically 0.5–2 mm, mean 0.8 mm),

- generate highly localized cell injury,

- induce pyknosis, necrosis, and progressive fibrosis over subsequent weeks.

This short-range cytotoxicity spares adjacent structures—including the parathyroid glands—substantially reducing the risk of hypoparathyroidism.

Selective destruction.

In hyperthyroid cats, normal thyroid tissue is usually suppressed by low endogenous TSH levels and therefore takes up minimal 131I. This endogenous suppression optimizes therapeutic selectivity by focusing the radiation burden on the diseased tissue.

2.2 Thyroid Uptake Kinetics

Biological and effective half-life.

While the physical half-life of ^131I is 8.04 days, the effective half-life in hyperthyroid cats is shorter—approximately 2.3 to 2.54 days—reflecting both physical decay and biological elimination.

Renal clearance.

Elimination of circulating 131I occurs primarily via renal excretion. Cats with renal disease may retain 131I longer, increasing total radiation burden and necessitating more cautious monitoring.

Role of uptake measurement.

In individualized radioiodine dosing protocols, 24-hour thyroidal 131I uptake is measured to refine and optimize the total therapeutic dose. This uptake assessment serves as a physiologic indicator of how efficiently the thyroid tissue concentrates radioiodine, allowing clinicians to adjust the administered activity accordingly. Low uptake values signal reduced radioiodine concentration and therefore pose a risk of undertreatment, potentially leading to persistent hyperthyroidism.

Conversely, high uptake values increase the likelihood of excessive radiation delivery, elevating the risk of iatrogenic hypothyroidism. As such, measuring thyroidal 131I uptake is pivotal for balancing therapeutic efficacy with preservation of normal endocrine function, and it represents a central component of individualized dosing algorithms.

2.3 Veterinary Dosimetry Considerations

Modern veterinary dosimetry emphasizes delivering the lowest effective dose to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing complications such as hypothyroidism and azotemia.

The individualized 2-day dosage algorithm used by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) integrates multiple quantitative metrics.

Day 1: Initial Dose Calculation

The initial composite dose score is calculated using three independent indicators of disease severity:

- Serum T4 and T3 concentrations

- Thyroid tumor volume, quantified via scintigraphy

- Tumor volume contributes roughly 1 mCi per cm³ to the dose score.

- Technetium uptake (TcTU)

- Assesses functional metabolic activity.

Only 80 percent of the calculated composite dose is administered on Day 1 to avoid overtreatment.

Day 2: Dose Adjustment

After 24 hours:

- the percent thyroidal 131I uptake is measured, and

- additional activity is administered to ensure an appropriate total absorbed dose, typically targeting 200 μCi per cm³ of tumor tissue.

This dynamic adjustment accounts for individual variation in tumor perfusion, iodine trapping ability, and physiological clearance.

In the study cohort, the median total dose was 1.9 mCi, and 1380 of 1400 cats required supplemental dosing on Day 2—underscoring the clinical necessity of this two-phase strategy.

2.4 Radiation Handling and Safety Requirements

The use of 131I mandates stringent compliance with radiation-safety policies grounded in the ALARA principle (as low as reasonably achievable).

Facility and Instrumentation Requirements

- Licensing: A valid Radioactive Materials (RAM) license is required, with designated Authorized Users (AUs) and a Radiation Safety Officer (RSO).

- Instrumentation:

- Gamma camera for scintigraphy

- Dose calibrator if manipulating doses

- Survey meter/Geiger counter (e.g., Ludlum 14C or Model 3 with 44-9 probe)

- Shielding: Lead shielding is mandatory; low-density materials are inadequate.

- Drug preparation and administration: In cats, 131I is administered as Na131I by subcutaneous injection, reducing exposure risk compared to IV administration.

Occupational Safety

- Monitoring: AUs and staff wear whole-body and ring dosimeters; annual occupational limits are 5000 mrem (target under 500 mrem ALARA).

- Contamination control: Gloves, lab coats, and closed shoes required.

- Thyroid bioassays: Performed 48–72 hours post-handling to detect accidental internal contamination.

- Pregnancy precautions: Pregnant workers are universally excluded from 131I operations due to fetal sensitivity.

Patient Confinement and Release

- Hospitalization: Cats must remain in restricted-access isolation areas. In the U.S., typical confinement is ≥96 hours, longer if radiation levels remain elevated.

- Release criteria: Most jurisdictions require < 0.25 mR/h at 1 ft (30 cm) to ensure public exposure remains <100 mrem/year.

Public Safety After Discharge

- Restricted contact: No contact with pregnant women or children for two weeks.

- General handling: Limited petting, no co-sleeping, no prolonged lap time for the same period.

- Waste disposal:

- Use of flushable litter is preferred.

- If flushing is not possible, litter must be stored for 80 days (~10 half-lives) before disposal.

Contaminated items: Bedding or toys used in isolation are treated as radioactive waste and not returned.

3. Components of the Dosing Algorithm

The individualized radioiodine dosing strategy designed by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) was developed to achieve a single therapeutic goal: resolve hyperthyroidism while minimizing the risk of iatrogenic hypothyroidism and the renal complications that follow.

The algorithm incorporates four major diagnostic elements, each contributing essential information about disease severity, functional thyroid burden, and clinical risk profile.

3.1 Serum Thyroid Hormone Indices

Serum concentrations of total thyroxine (TT₄) and total triiodothyronine (TT₃) provide critical insight into the biochemical severity of feline hyperthyroidism and play a central role in individualized radioiodine dosing. Within the algorithm, TT₄ and TT₃ values generate one of the three dose scores that contribute to the initial composite 131I dose; when the two hormones fall into different severity tiers, their respective scores are averaged to better represent overall disease activity. Higher TT₄ and TT₃ concentrations correlate with greater functional tumor burden, and TT₃ may, in some cases, offer a more accurate reflection of disease severity than TT₄ alone. To capture this continuum of metabolic hyperactivity, the algorithm uses a graded scale in which progressively elevated hormone concentrations correspond to increasingly higher dose scores, ranging approximately from 1.3 to 8.5 mCi. These hormone-based indices ensure that the dosing framework incorporates biochemical hyperfunction, rather than relying solely on structural thyroid size.

3.2 Thyroid Tumor Volume

Anatomical disease burden is incorporated into the dosing algorithm through direct measurement of thyroid tumor volume. This volume is quantified using thyroid scintigraphy, which enables accurate assessment of the functional thyroid mass contributing to hormone excess. Tumor volume generates the second dosing score, following the principle of administering approximately 1 mCi (37 MBq) of 131I per cm³ of hyperfunctional tissue. Larger tumor volumes correlate with more advanced disease and therefore predict a need for higher therapeutic activity. By integrating this structural parameter, the algorithm ensures that radioiodine dosing reflects not only biochemical hyperactivity but also the physical extent of hyperfunctional thyroid tissue.

3.3 Technetium Uptake (TcTU)

Technetium thyroid uptake (TcTU) provides a dynamic assessment of metabolic activity and the iodine-trapping capacity of hyperfunctional thyroid tissue. This parameter is measured during thyroid scintigraphy as the percentage uptake of sodium 99mTc-pertechnetate, offering a functional counterpart to anatomical volume measurements. TcTU correlates strongly with circulating TT₄ and TT₃ concentrations as well as estimated thyroid tumor volume, making it one of the most sensitive indicators of overall goiter activity and functional disease severity. Within the individualized dosing framework, TcTU contributes the second major dose score used in the Day-1 composite calculation. Notably, cats that remained hyperthyroid after radioiodine treatment tended to exhibit higher TcTU values and more severe scintigraphic profiles, whereas cats that developed iatrogenic hypothyroidism often had milder pre-treatment severity scores. In this way, TcTU provides a metabolic counterbalance to structural tumor volume, ensuring that the dosing algorithm accounts for both functional and anatomical drivers of hormone excess.

3.4 Day-2 Thyroidal 131I Uptake Measurement (Dose Adjustment)

On Day 2 of the individualized dosing protocol, a direct measurement of 24-hour thyroidal 131I uptake is obtained—representing the algorithm’s defining and most discriminating refinement step. This uptake value quantifies how efficiently the hyperfunctional thyroid tissue concentrates radioiodine and therefore determines whether supplemental ^131I activity is required. Cats with low uptake receive inadequate radiation from the initial Day-1 dose and thus require additional activity to avoid under-treatment, whereas cats with high uptake may risk excessive radiation exposure, prompting a downward adjustment in supplemental dosing to prevent iatrogenic hypothyroidism. In clinical application, this step proved essential: in the study cohort, 1380 of 1400 cats required dose modification based on the uptake measurement. The algorithm aims to deliver approximately 200 μCi per cm³ of tumor tissue, ensuring that the absorbed dose aligns with the tumor’s true concentrating ability. This individualized refinement is a capability fundamentally absent from fixed-dose protocols and underscores the superiority of physiology-based dosimetry.

3.5 Clinical Severity Considerations (Prognostic Markers)

While TT₄/TT₃, tumor volume, and TcTU determine the mathematical dose calculation, clinical factors provide essential prognostic context.

Renal Markers (Creatinine, SDMA, USG)

Hyperthyroidism artificially elevates GFR; restoring euthyroidism may unmask chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- Cats developing iatrogenic hypothyroidism are more likely to become azotemic.

- Cats destined for hypothyroidism were significantly older and had higher pretreatment creatinine, urea, and SDMA.

- A USG < 1.035 predicted masked post-treatment azotemia with 86.1% sensitivity.

- Long-term monitoring of creatinine, TT₄, and TSH (6–12 months) is essential for assessing outcome.

Clinical Risk Profiles

Characteristic patterns emerged:

- Cats at risk for iatrogenic hypothyroidism were often older, female, had bilateral nodules, detectable TSH, and lower severity scores.

- Cats at risk for treatment failure (persistent hyperthyroidism) tended to be younger, had higher severity scores, and showed low Day-2 uptake.

These markers help clinicians interpret algorithmic results in light of individual physiologic risks.

4. Two-Step Individualized Dose Calculation

The individualized radioiodine (131I) dosing protocol developed by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) uses a two-step, physiologically informed dosing method designed to determine the lowest effective dose needed to cure hyperthyroidism while minimizing the risk of iatrogenic hypothyroidism and subsequent azotemia. Despite a markedly reduced median total dose of 1.9 mCi (range, 1.0–10.6 mCi), the algorithm achieved cure rates comparable to traditional fixed-dose approaches.

Day 1 focuses on estimating disease severity using quantitative, objective metrics. Day 2 provides a biologically individualized adjustment based on the cat’s actual 131I uptake.

4.1 Day 1: Composite Dose Calculation

On Day 1, the initial radioiodine activity is determined by calculating a composite 131I dose score derived from three indices of hyperthyroid disease severity:

- Serum Thyroid Hormone Concentrations (T₄ and T₃)

Total thyroxine (TT₄) and total triiodothyronine (TT₃) concentrations reflect biochemical severity.

- TT₄ and TT₃ each generate a dose score using a graded severity table.

- If TT₄ and TT₃ fall into different categories, their respective scores are averaged to form the thyroid hormone score.

- Higher values correspond to more severe disease and therefore higher initial dose requirements.

- Technetium Uptake (TcTU)

TcTU represents the functional metabolic activity of the thyroid tissue.

- Measured as percentage uptake of ⁹⁹ᵐTc-pertechnetate via quantitative thyroid scintigraphy.

- Provides one of the most sensitive assessments of hyperfunctional gland behavior.

- TcTU receives its own dose score via a graded table and strongly correlates with functional thyroid burden.

- Thyroid Tumor Volume

Anatomical burden is measured via scintigraphic estimation of thyroid tumor volume.

- Dose score calculated using the rule: 1 mCi per cm³ of tumor tissue.

- Larger volumes contribute more heavily to the final score.

Initial Dose Administration on Day 1

The three individual dose scores (T₄/T₃, TcTU, tumor volume) are averaged to produce the Day-1 composite dose score.

To reduce the risk of overtreatment in cats with unexpectedly high iodine uptake, only 80 percent of this composite score is administered on Day 1.

This precautionary reduction ensures safety while allowing for physiologically based refinement on Day 2.

4.2 Day 2: Supplemental Adjustment

Approximately twenty-four hours after the initial administration, the cat undergoes a critical reassessment step.

- Measure 24-Hour Thyroidal 131I Uptake

This measurement quantifies the tumor’s actual ability to concentrate 131I.

- Directly reflects the functional activity and iodine-trapping efficiency of the adenomatous tissue.

- Is essential for determining whether the Day-1 dose was sufficient or requires adjustment.

- Administer Additional 131I Activity (if needed)

Based on the measured uptake, clinicians calculate the supplemental activity required to deliver the appropriate absorbed radiation dose.

- Target dose is approximately 200 μCi per cm³ of tumor tissue.

Low uptake necessitates additional activity to avoid undertreatment; high uptake may require little or no supplemental activity.

Flowchart showing protocol for calculating initial (day 1), composite 131I dose based on 3 measures of disease severity (serum T4 and T3 concentrations, TcTU, and thyroid tumor volume). On day 2, thyroid 131I uptake was measured and additional 131I activity administered as needed

For detail information please check the original paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8478068/

5. Evidence for Precision-Based Radioiodine Therapy

The individualized 131I dosing algorithm developed by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) represents a major advancement in feline hyperthyroid management. By integrating biochemical, metabolic, and anatomical parameters with a physiologic uptake assessment, the protocol achieves high therapeutic effectiveness while markedly reducing the incidence of post-treatment hypothyroidism and azotemia. This approach contrasts strongly with traditional fixed-dose methods, which often expose cats—particularly those with mild disease—to unnecessarily high radiation doses.

5.1 Results From J Vet Intern Med (2021)

In their prospective case series of 1,400 hyperthyroid cats, Peterson and Rishniw (21demonstrated that individualizing the 131I dose according to disease severity produced excellent outcomes. The median administered dose was only 1.9 mCi (range 1.0–10.6 mCi), a substantial reduction compared with the 3–5 mCi typically delivered in most fixed-dose protocols. Despite this lower dosing, therapeutic efficacy remained high.

The study reported that 74.8 percent of cats achieved euthyroidism. This cure rate is consistent with historical outcomes achieved using significantly higher and less personalized doses, suggesting that many cats have been receiving more radiation than necessary in conventional practice.

A major strength of the individualized dosing approach lies in its reduction of iatrogenic hypothyroidism (IH). Only 4.1 percent of treated cats developed overt IH, and 17.1 percent developed subclinical IH, for a total rate of 21.2 percent. These values are considerably lower than the 30–80 percent incidence commonly cited for fixed-dose strategies.

The individualized protocol also reduced the development of post-treatment azotemia. Across all cats, azotemia occurred in 18.8 percent, but its prevalence varied markedly depending on thyroid outcome. Only 14.2 percent of euthyroid cats developed azotemia, compared with 39.6 percent of subclinically hypothyroid cats and 71.9 percent of overtly hypothyroid cats. These findings reinforce the direct relationship between post-treatment hypothyroidism and renal impairment.

5.2 Comparison with Traditional Fixed-Dose Protocols

Traditional radioiodine protocols administer the same 3–5 mCi dose to nearly all cats, regardless of disease severity. This approach inevitably leads to overtreatment in a large subset of patients, particularly those with mild or moderate hyperthyroidism. Because fixed-dose methods cannot distinguish between mild and severe disease, they often deliver an unnecessary radiation excess that destroys residual normal thyroid tissue, producing high rates of iatrogenic hypothyroidism.

By contrast, the individualized dosing algorithm aligns the administered dose with the cat’s actual disease burden. Biochemical severity (T₄/T₃), functional activity (TcTU), structural burden (tumor volume), and physiologic iodine handling (Day-2 131I uptake) are integrated into a composite assessment that determines the minimal effective dose. This precision-based method ensures that cats with mild disease receive appropriately low doses.

Nearly all cats with mild to moderate hyperthyroidism responded to <2 mCi, which is lower than even the smallest doses commonly used in fixed-dose protocols. Conversely, cats with severe hyperthyroidism, very high turnover, or large tumor volumes sometimes required up to 10 mCi, illustrating the breadth of inter-individual variation that fixed-dose approaches cannot accommodate.

Reducing the administered dose translates directly into fewer cases of iatrogenic hypothyroidism. Preserving thyroid function is essential for renal protection, as hyperthyroidism elevates the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and masks underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD). When euthyroidism is restored too abruptly—or when hypothyroidism develops—GFR declines sharply, unmasking azotemia. Because azotemic hypothyroid cats experience significantly shorter survival times, minimizing IH is critical for long-term outcomes.

6. Post-Therapy Monitoring and Follow-Up

Successful long-term management of feline hyperthyroidism following radioiodine (131I) therapy depends heavily on structured post-treatment monitoring. The individualized dosing protocol developed by Peterson and Rishniw (20211) emphasizes the importance of reassessing both thyroid and renal function during the months following treatment. These follow-up evaluations are designed to confirm restoration of euthyroidism, detect the development of iatrogenic hypothyroidism (IH), and identify unmasked chronic kidney disease (CKD). Most monitoring protocols recommend a comprehensive evaluation 6 to 12 months after treatment, aligning with the time required for stabilization of thyroid hormone regulation and renal physiology.

6.1 Hormone Normalization Timeline

Thyroid hormone concentrations begin to normalize shortly after 131I administration, but the pace of stabilization varies among cats. Serum T₄ typically declines into the reference range within 4 to 12 weeks, with many cats becoming clinically euthyroid within 1 to 3 weeks. Despite this early normalization, the full therapeutic effect—including complete ablation of hyperfunctional tissue and long-term fibrosis—may take up to six months.

For this reason, definitive classification of thyroid status is usually reserved for the 6- to 12-month re-evaluation window. Major studies report median evaluation times between 6.2 and 6.8 months, reflecting the time needed for full biologic response to therapy. Additionally, pituitary thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) production requires several months to recover from the suppressive hyperthyroid state. Pituitary thyrotrophs generally regain normal function by approximately three months post-treatment, which is why early post-treatment TSH measurement may not accurately reflect thyroid status.

6.2 Renal Function Monitoring

Monitoring renal function is essential following radioiodine therapy because hyperthyroidism artificially elevates glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Once euthyroidism is restored, the decline in GFR can unmask pre-existing CKD. Follow-up evaluations typically include measurements of T₄, TSH, and creatinine at 6 to 12 months, though some clinicians also incorporate assessments at 1, 3, and 6 months, with ongoing monitoring every six months thereafter.

In the individualized dosing study, 18.8 percent of cats developed azotemia (creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL). Most cases of post-treatment azotemia emerged within four weeks of therapy, after which renal function tended to stabilize. Importantly, the development of iatrogenic hypothyroidism significantly increases the likelihood of azotemia. In the study, 71.9 percent of overtly hypothyroid cats and 39.6 percent of subclinically hypothyroid cats became azotemic, compared with only 14.2 percent of euthyroid cats. Hypothyroid cats that develop azotemia also have shorter survival times than their non-azotemic counterparts.

Urine specific gravity (USG) is another valuable marker. A pretreatment USG < 1.035 demonstrated 86.1 percent sensitivity for predicting the development of masked CKD after treatment. Cats that became azotemic also had lower post-treatment USG values than those that remained non-azotemic.

When azotemia occurs in conjunction with hypothyroidism, levothyroxine supplementation is recommended to restore euthyroidism and improve renal perfusion. Increasing GFR through thyroid hormone supplementation can resolve the pre-renal component of the azotemia and stabilize renal parameters.

6.3 Detecting Subclinical Hypothyroidism

Subclinical hypothyroidism is relatively common after radioiodine therapy and carries meaningful clinical implications, especially regarding renal function. In the individualized dosing study, 17.1 percent of cats developed subclinical hypothyroidism while 4.1 percent developed overt hypothyroidism, giving a total IH prevalence of 21.2 percent—substantially lower than the 30–80 percent rates reported for fixed-dose methods.

Diagnosis relies on concurrent measurement of T₄ and TSH, as T₄ alone can be misleading in cats with non-thyroidal illness (NTI).

- Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as T₄ within the reference interval (1.0–3.8 μg/dL) with TSH > 0.30 ng/mL.

- Overt hypothyroidism is defined as T₄ < 1.0 μg/dL with TSH > 0.30 ng/mL.

An elevated TSH is particularly useful because it is highly sensitive for detecting iatrogenic hypothyroidism. It also helps differentiate azotemic hypothyroidism (where thyroid dysfunction contributes to reduced GFR) from azotemic non-thyroidal illness, which is crucial for correct therapeutic decision-making.

Hypothyroidism can be transient. In untreated cats, median time to normalization of T₄ and TSH was approximately six months, although 25 percent of cats required twelve months or more to fully resolve.

6.4 Imaging or Repeat Assessments When Indicated

Outcome classification relies on the combined interpretation of T₄ and TSH. Persistent hyperthyroidism is defined by T₄ ≥ 3.9 μg/dL with TSH < 0.03 ng/mL at the 6- to 12-month recheck. In the individualized dosing study, 4 percent of cats remained hyperthyroid at this interval. Encouragingly, most cats that remain hyperthyroid at six months respond well to a second 131I treatment.

Repeat thyroid scintigraphy can serve as a valuable adjunct. It allows confirmation of persistent functional thyroid tissue, assessment of tumor size reduction, and identification of residual nodules. In the Peterson and Rishniw study, 11 percent of cats had persistent “hot” nodules on follow-up scintigraphy but were clinically euthyroid based on bloodwork. Thus, focal scintigraphic uptake does not necessarily indicate treatment failure. Conversely, 71 percent of cats with little or no visible thyroid tissue on scintigraphy were confirmed to be hypothyroid, illustrating the strong relationship between imaging and functional outcome.

While scintigraphy provides important structural and functional information, serum thyroid hormone profiles remain the gold standard for determining post-treatment thyroid status, particularly in cases of mild hypothyroidism.

If a cat remains hyperthyroid following two courses of 131I therapy, clinicians should consider the possibility of thyroid carcinoma, although this remains rare in the general hyperthyroid population.

7. Discussion

The individualized 131I dosing protocol pioneered by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) represents a substantial evolution in the treatment of feline hyperthyroidism. Unlike traditional fixed-dose methods, which cannot account for the profound heterogeneity in disease severity among patients, this precision-based strategy systematically integrates biochemical, functional, and anatomical data to determine the minimal dose necessary to achieve a cure. Its clinical impact, however, must be considered alongside its practical limitations and the emerging technological innovations that may help refine or simplify its implementation.

7.1 Clinical Significance of Individualized Dosing

The individualized dosing algorithm’s primary clinical strength lies in its ability to align radiation activity with the actual biological characteristics of the patient’s disease. By tailoring the dose to each cat’s thyroid hormone concentrations, scintigraphic tumor volume, technetium uptake (TcTU), and 24-hour 131I uptake, the method provides a level of dosing accuracy not achievable with fixed-dose protocols.

This precision enables the use of a much lower median dose—1.9 mCi—while maintaining cure rates comparable to historical standards. Cats with mild or moderate hyperthyroidism often require <2 mCi, doses far below the standard 3–5 mCi commonly administered. The algorithm also ensures that cats with severe disease or larger tumor burdens receive appropriately higher doses, sometimes reaching 10 mCi, which exceeds the upper limits used by many variable or fixed-dose methods.

The integration of multiple objective metrics also mirrors human nuclear medicine protocols, where thyroid volume and iodine uptake strongly influence dosing. This approach underscores a shift toward evidence-based, individualized treatment, reducing both under- and over-treatment.

7.2 Reduction in Treatment-Related Morbidity

A pivotal advantage of individualized dosing is its ability to reduce the major morbidities associated with traditional fixed-dose protocols: iatrogenic hypothyroidism (IH) and post-treatment azotemia. Fixed-dose methods routinely expose cats to excessive radiation, resulting in IH rates of 30–80 percent within six months of therapy.

In contrast, the individualized algorithm achieved a markedly lower total IH rate of 21.2 percent (overt + subclinical). This reduction is clinically meaningful because hypothyroid cats may require lifelong L-thyroxine supplementation, which suppresses endogenous TSH and limits recovery of the residual normal thyroid tissue.

Equally important is the algorithm’s contribution to renal protection. Hyperthyroidism raises GFR and can mask early CKD; restoring euthyroidism reduces GFR and may unmask renal insufficiency. Because IH further depresses GFR, hypothyroid cats are far more likely to develop azotemia. In the study, only 14.2 percent of euthyroid cats became azotemic, compared with 71.9 percent of overtly hypothyroid cats. Reducing the prevalence of IH therefore directly supports long-term renal health and improves overall survival outcomes.

An additional benefit involves radiation exposure. Lower median 131I doses naturally reduce environmental radiation risk to veterinary personnel and pet owners, aligning with the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) safety principle.

7.3 Practical Implementation Challenges

Although clinically superior, the individualized dosing method presents practical obstacles that may limit widespread adoption. One major challenge is the requirement for specialized nuclear medicine equipment, including a gamma camera for scintigraphy, a dose calibrator for measurement and preparation of radioiodine doses, and a survey meter to determine 24-hour uptake. These instruments are expensive, require radiation-licensed facilities, and are not widely accessible in general veterinary practice.

The protocol is also inherently more labor-intensive than fixed-dose methods. It requires a two-day process involving initial dose calculation, Day-1 administration, Day-2 uptake measurement, and supplemental dosing. In the original study, 1380 out of 1400 cats required additional activity on Day 2, highlighting the necessity of this second-day adjustment.

Radiation safety considerations add another layer of complexity. Performing uptake measurements requires that veterinary staff be trained in radiation handling and safety procedures. Facilities must operate under a RAM license and employ an Authorized User (AU) and Radiation Safety Officer (RSO). Although the additional radiation exposure from measuring uptake is brief (typically <3 minutes), it nonetheless requires strict adherence to ALARA principles and procedural oversight.

7.4 Future Integration with Digital Dosimetry and AI-Assisted Volume Estimation

Looking ahead, digital and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies offer opportunities to streamline individualized dosing, even though the original sources do not describe AI tools specific to this algorithm. The current protocol already employs digital dosimetry tools, such as spreadsheet-based calculators, to integrate Day-1 measurements and generate the initial composite dose and final adjusted dose.

Advancements in AI-driven image analysis may further simplify or automate critical components. Thyroid tumor volume is a major determinant of initial dosing, and AI-based segmentation tools are increasingly being used to analyze medical imaging, including radiographs, ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Applying such tools to thyroid scintigraphy could improve the speed and consistency of volumetric assessment, reduce operator variability, and produce more standardized dose calculations.

AI could also help refine evaluation of post-treatment scintigraphy, which currently offers limited sensitivity (62.3 percent) for detecting mild hypothyroidism. More sophisticated quantitative approaches might assist in better correlating scintigraphic uptake patterns with biochemical thyroid status.

Digital monitoring systems may also enhance longitudinal follow-up by integrating T₄, TSH, creatinine, SDMA, and USG into predictive models that estimate a cat’s risk of developing IH or azotemia after therapy.

Although these innovations remain largely theoretical in the context of 131I dosing, the movement toward individualized treatment reflects a broader shift in internal medicine: replacing standardized templates with precision therapeutics, where treatment intensity is calibrated to biological need rather than historical convention.

8. Conclusion

The individualized 131I dosing algorithm developed by Peterson and Rishniw (2021) represents a transformative advancement in the management of feline hyperthyroidism. By replacing the conventional one-size-fits-all fixed-dose model with a structured, physiology-driven, and quantitatively informed approach, the algorithm achieves a rare balance: maximizing therapeutic success while minimizing treatment-associated morbidity.

Through the integration of serum thyroid hormone concentrations, Technetium uptake (TcTU), thyroid tumor volume, and 24-hour 131I uptake, the dosing strategy ensures that each cat receives precisely the amount of radioiodine required to resolve hyperthyroidism—no more, no less. This refinement results in a median administered dose of only 1.9 mCi, far lower than traditional protocols, without compromising cure rates. The reduction in radiation exposure is clinically significant not only for feline patients but also for veterinary staff and pet owners under the ALARA framework.

Perhaps the most impactful benefit of individualized dosing is its dramatic reduction in iatrogenic hypothyroidism (IH) and post-treatment azotemia, two major complications long associated with fixed-dose therapy. By preserving residual normal thyroid function and preventing excessive reductions in glomerular filtration rate, the algorithm directly supports renal health and long-term survival—outcomes that are central to quality of life in aging feline populations.

Despite its clinical advantages, practical limitations remain. The protocol requires specialized nuclear medicine equipment, trained personnel, licensed facilities, and a commitment to a multi-day treatment workflow. For many practices, these resource constraints pose real barriers to adoption. However, as digital tools, automated dosimetry systems, and AI-assisted imaging continue to evolve, these obstacles may diminish. Future technological integration could streamline dose calculations, improve volumetric consistency, and broaden accessibility to individualized radioiodine therapy.

In summary, the individualized 131I dosing algorithm represents a shift toward precision nuclear endocrinology in veterinary medicine. It embodies the principle that effective treatment is not defined by higher doses, but by appropriately targeted doses tailored to the biological behavior of each patient’s disease. As the field continues to advance, this approach provides a strong foundation for safer, more effective, and more personalized management of feline hyperthyroidism.

A central challenge in individualized radioiodine therapy is the need for rapid, accurate biochemical monitoring, particularly because the return to euthyroidism can unmask underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD). The dosing model by Peterson and Rishniw emphasizes assessing creatinine, urea, SDMA, phosphorus, and electrolytes both before treatment—when hyperthyroidism artificially elevates GFR—and again within 4–12 weeks post-therapy, when azotemia is most likely to appear. This requires fast, reliable point-of-care chemistry testing to distinguish reversible hemodynamic changes from true renal pathology.

The Bioguard miniCHEM Veterinary Chemistry Analyzer directly supports this requirement. By delivering rapid, high-precision results from very small sample volumes, miniCHEM enables clinics to perform safe pre-treatment screening, detect early post-I-131 azotemia, and guide timely decisions regarding thyroid supplementation or renal management. In this way, miniCHEM serves as an essential diagnostic link between nuclear endocrinology and ongoing biochemical monitoring, enhancing patient safety and treatment precision.

Category | miniCHEM Specification |

Primary Function | Fully automated veterinary chemistry analyzer for in-clinic biochemical testing |

Turnaround Time | Fast results, enabling same-visit renal and metabolic evaluation |

Sample Type & Volume | Works with whole blood, serum, or plasma; requires only a small sample volume, ideal for feline patients |

Compatible Test Panels | Kidney Function 11 Test Panel, Liver Function 12 Panel, Electrolyte Panel, General Health Profiles (as listed on Bioguard website) |

Kidney-Related Analytes | ALB, PHOS, BUN, CRE, Ca, CO₂, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, GLU, BUN/CRE — essential for detecting masked CKD and monitoring post-treatment azotemia |

References:

Peterson, M. E., & Rishniw, M. (2021). A dosing algorithm for individualized radioiodine treatment of cats with hyperthyroidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 35(5), 2140–2151. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16228

Peterson, M. E., & Rishniw, M. (2022). Predicting outcomes in hyperthyroid cats treated with radioiodine. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 36(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16319

Peterson, M. E., & Rishniw, M. (2023). Urine concentrating ability in cats with hyperthyroidism: Influence of radioiodine treatment, masked azotemia, and iatrogenic hypothyroidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 37(6), 2039–2051. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.16849

Boag, A. K., Neiger, R., Slater, L., Stevens, K. B., Haller, M., & Church, D. B. (2007).

Changes in the glomerular filtration rate of 27 cats with hyperthyroidism after treatment with radioactive iodine. The Veterinary Record, 161(21), 711–715. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.161.21.711

Stammeleer, L., Xifra, P., Serrano, S. I., Vandermeulen, E., Daminet, S., & Peterson, M. E. (2025).

Thyroid scintigraphy findings in 234 hyperthyroid cats before and after radioiodine treatment. Animals, 15(10), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15101495

Peterson, M. E., Guterl, J. N., Rishniw, M., & Broome, M. R. (2016).

Evaluation of quantitative thyroid scintigraphy for diagnosis and staging of disease severity in cats with hyperthyroidism. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 57(4), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/vru.12360

Lucy, J. M., Peterson, M. E., Randolph, J. F., et al. (2017).

Efficacy of low-dose (2 millicurie) vs. standard-dose (4 millicurie) radioiodine treatment for cats with mild-to-moderate hyperthyroidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 31, 326–334.

Morre, W. A., Panciera, D. L., Daniel, G. B., et al. (2018).

Investigation of a novel variable dosing protocol for radioiodine treatment of feline hyperthyroidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 32, 1856–1863.

Williams, T. L., Elliott, J., & Syme, H. M. (2010).

Association of iatrogenic hypothyroidism with azotemia and reduced survival time in cats treated for hyperthyroidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 24, 1086–1092.

Jefferson, T., Dooley, L., Ferroni, E., Al-Ansary, L. A., van Driel, M. L., Bawazeer, G. A., Jones, M. A., Hoffmann, T. C., Clark, J., Beller, E. M., Glasziou, P. P., & Conly, J. M. (2023).

Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023(1), Article CD006207. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub6