Table of Contents

1. Introduction

While many mammals exhibit sexual dimorphism, at least 50% of extant bird species are sexually monomorphic, meaning their biological sex cannot be reliably determined by external appearance. In these species, particularly nestlings and juveniles, males and females often look identical, making visual identification difficult or impossible. Exceptions exist in some species, such as peacocks and pheasants (family Phasianidae), where males display bright iridescent plumage and distinct markings, while females have relatively dull and cryptic coloration.

Accurately determining a bird’s sex is essential for veterinary practitioners, ornithologists, and aviculturists, supporting evolutionary studies, management of zoological collections, and avian breeding and conservation programs. Proper sex identification ensures appropriate pairing for reproduction, preventing social stress or infertility caused by inadvertent same-sex pairings.

Gender knowledge is also critical for diagnosing sex-specific diseases. Life-threatening conditions such as egg binding, ovarian cysts, oophoritis, and salpingitis occur exclusively in females, whereas males may be affected by orchitis or testicular neoplasia. Furthermore, knowing a bird’s sex aids in owner education, preparing caretakers for behaviors such as broodiness in females or territorial aggression in males.

2. Traditional Sexing Methods

Traditional bird sexing has historically relied on visual, behavioral, and biological indicators, but these approaches face significant challenges in species that are sexually monomorphic, where males and females appear identical to the human eye.

Visual and Behavioral Analysis

- Morphological Differences: In sexually dimorphic species such as the common pheasant, identification is straightforward: roosters display bright iridescent plumage and distinct facial markings, while hens exhibit relatively dull coloration. However, morphological cues are impossible to discern in most nestlings and unreliable for at least 50% of extant bird species.

- Behavioral Observation: This involves monitoring gender-specific roles during courtship or nesting, such as the “mounting” male or “mounted” female. A major limitation is that avian behavior is fluid; same-sex pairs may court, mate, or attempt to incubate infertile eggs, making observation an unreliable indicator of biological sex.

- Acoustic Analysis: Some species exhibit sex-specific vocalizations, such as certain duck whistles or calls of the Imperial Cormorant, but acoustic methods are species-limited and cannot be universally applied.

Surgical and Invasive Procedures

- Laparoscopic Examination and Laparotomy: These surgical methods, performed under general anesthesia, allow direct visualization of reproductive organs such as ovaries or testes. While accurate, they are invasive, costly, and carry significant risk, particularly for endangered or fragile species.

- Vent Sexing (Cloacal Examination): Commonly used in poultry, this method applies pressure to evert the vent and inspect for a primordial phallus. With proper training, accuracy can exceed 98%, but subtle female anatomy may lead to mis-sexing, and handling stress can impact the bird’s health.

Laboratory-Based Methods

- Steroid Sexing: Measures the ratio of estrogen to androgen in fecal or plasma samples. Although non-invasive, the method is time-consuming, ambiguous, and prone to inaccuracies.

- Chromosome Inspection (Karyotyping): Identifies Z and W sex chromosomes under the microscope. While scientifically rigorous, it is expensive, slow, and impractical for routine or commercial use.

Limitations of Traditional Methods

Traditional methods are often time-intensive, costly, and prone to error. Surgical techniques like laparoscopy carry a real risk of fatal hemorrhage or anesthesia complications, while visual cues may fail entirely because many birds exhibit sexual dimorphism only in the ultraviolet spectrum, which humans cannot perceive.

3. DNA-Based Sexing

Molecular sexing has emerged as a fast, highly accurate, and non-invasive alternative to traditional methods like visual observation or surgical examination. With accuracy rates exceeding 99.9%, it is now considered the gold standard for determining the gender of sexually monomorphic species. Unlike invasive procedures, DNA sexing can be performed using minimal biological material, such as plucked feathers, eggshell membranes, or a single drop of blood, making it safe for the bird and practical for routine or commercial use.

3.1 Sex Determination in Birds

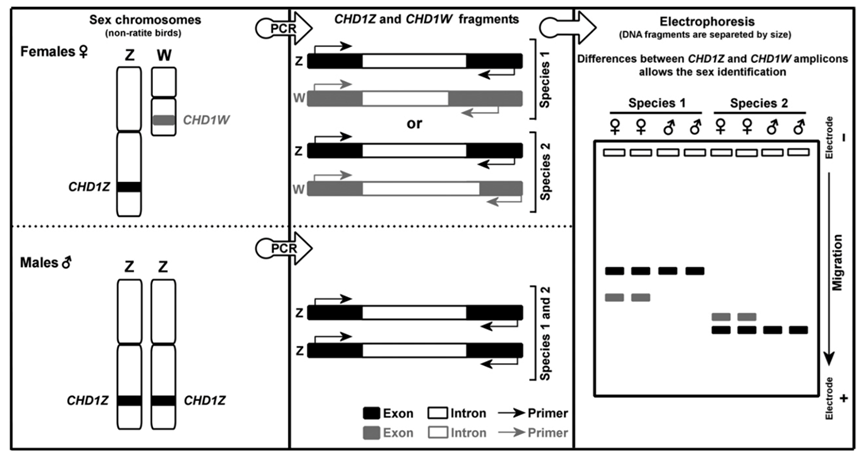

Birds employ the ZW sex-determination system, which differs from the XY system in mammals:

- Mammals: Females are homogametic (XX), while males are heterogametic (XY); consequently, the sperm determines the offspring’s sex.

- Birds: Females are heterogametic (ZW), carrying two different sex chromosomes, while males are homogametic (ZZ), carrying two identical Z chromosomes. In this system, the ovum determines the sex of the offspring.

3.2 PCR-Based Methods

The most reliable method for molecular sexing is Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) targeting the CHD1 gene (Chromodomain Helicase DNA Binding Protein 1), which is highly conserved across almost all avian species.

- CHD1 Gene Introns: The CHD1 gene is present on both Z and W chromosomes. PCR amplifies specific introns (non-coding regions) that differ in length between the Z and W chromosomes, allowing accurate sex discrimination.

- Interpretation of Results: After amplification, the number of amplicons indicates the bird’s sex:

- Males (ZZ): Single CHD amplicon, as both Z chromosomes are identical.

- Females (ZW): Two distinct CHD amplicons, representing CHD-Z and CHD-W alleles.

- Other PCR-Based Techniques: Alternative molecular methods include SSCP (Single-Strand Conformation Polymorphism), RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism), and AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism), though these are generally less practical for routine commercial use.

A comparative review of PCR-based methods is presented in Fig. 1 (Morinha et al., 2012).

4. Conclusion

DNA-based sexing has transformed avian gender identification, especially for sexually monomorphic species, where traditional methods can be inaccurate, invasive, or time-consuming.

Bioguard’s PCR-based molecular sexing provides a fast, highly accurate (>99.99%), and non-invasive solution. By using small samples of feathers, eggshell membranes, or blood, Bioguard allows breeders, veterinarians, and conservationists to efficiently:

- Pair birds for breeding and conservation programs

- Monitor gender-specific diseases

- Educate owners on sex-related behaviors

- Minimize stress and risk to birds by avoiding invasive procedures

Qmini Real-Time PCR, Bioguard’s advanced in-clinic PCR platform, streamlines this process. With optimized reagents and user-friendly protocols, Qmini enables rapid and reliable DNA-based sexing directly in the clinic or breeding facility, providing near-instant results without requiring specialized lab personnel. This integration of Bioguard expertise with Qmini technology ensures that bird gender determination is not only accurate but also accessible, convenient, and safe.

Bento Bioworks Ltd. (n.d.). Bird sexing – Test bird DNA for male or female. Retrieved from [source material]

Centeno-Cuadros, A., Tella, J. L., Delibes, M., Edelaar, P., & Carrete, M. (2018). Validation of loop-mediated isothermal amplification for fast and portable sex determination across the phylogeny of birds. Molecular Ecology Resources, 18(2), 251–263.

Cerit, H., & Avanus, K. (2007). Sex identification in avian species using DNA typing methods. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 63(1), 91–100.

CrazyBirdChick. (2016, September 11). Surgical sexing vs DNA sexing? [Forum thread]. Avian Avenue Parrot Forum.

Davitkov, D., Vucicevic, M., Glavinic, U., Skadric, I., Nesic, V., Stevanovic, J., & Stanimirovic, Z. (2021). Potential of inter- and intra-species variability of CHD1 gene in birds as a forensic tool. Acta Veterinaria-Beograd, 71(2), 147–157.

Echols, S., & Speer, B. (2022). Avian reproductive tract diseases and surgical resolutions. Clinical Theriogenology, 14, 32–43.

Fridolfsson, A. K., & Ellegren, H. (2000). Molecular evolution of the avian CHD1 genes on the Z and W sex chromosomes. Genetics, 155(4), 1903–1912.

HealthGene. (n.d.). DNA sexing [Newsletter/Website].

Je_dois_mourir. (n.d.). How do monomorphic parrots tell what sex other parrots are? [Reddit thread].

Kroczak, A., Wierzbicki, H., & Urantówka, A. D. (2022). The length polymorphism of the 9th intron in the avian CHD1 gene allows sex determination in some species of Palaeognathae. Genes, 13(3), 507.

Lloyd-Evans, T. (1998). Book review: Identification guide to North American birds, Part I by Peter Pyle, S. N. G. Howell, D. F. DeSante, R. P. Yunick, & M. Gustafson. Bird Observer, 26(4), 192–195.

Morinha, F., Cabral, J. A., & Bastos, E. (2012). Molecular sexing of birds: A comparative review of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods. Theriogenology, 78(4), 703–714.

Parrot Breeders Association of Southern Africa. (n.d.). Surgical sexing vs DNA sexing in parrots.

Quintana, F., López, G. C., & Somoza, G. (2008). A cheap and quick method for DNA-based sexing of birds. Waterbirds, 31(3), 485–488.

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (2013). Poultry Industry Manual.

van Harmelen, J. (2024). Chick sexing. In Densho Encyclopedia.