Individualized I-131 Dosing for Feline Hyperthyroidism Treatment

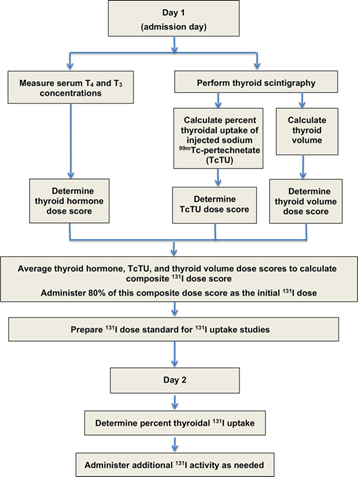

Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Overview of Feline Hyperthyroidism Feline hyperthyroidism is the most common endocrine disorder affecting middle-aged and geriatric cats, driven overwhelmingly by autonomous thyroid adenomas or adenomatous hyperplasia. More than 97 percent of cases result from benign, functional proliferation of thyroid tissue that produces excessive amounts of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) (Peterson, 2013; Broussard et al., 1995). The resulting hypermetabolic state manifests across multiple organ systems. Typical clinical signs include: Progressive weight loss, despite normal or increased appetite Polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria Episodic vomiting or diarrhea A dull or unkempt hair coat Tachycardia and a palpable thyroid nodule in many cases These signs often begin subtly, then intensify as thyroid hormone excess accelerates metabolic turnover and causes secondary strain on cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal systems. 1.2 Limitations of Traditional Radioiodine (I-131) Dosing Radioiodine (I-131) therapy is widely regarded as the treatment of choice for feline hyperthyroidism (Peterson, 2013; Mooney, 2001; Feldman & Nelson, 2015). I-131 concentrates selectively in hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, where emitted beta particles induce cytotoxicity and subsequent glandular fibrosis. Traditional fixed-dose approaches, typically ranging from 3–5 mCi, have historically produced good cure rates Peterson, 2013; Williams et al., 2010; Peterson & Broome, 2015). However, these protocols are increasingly recognized as imprecise, with substantial rates of treatment-related complications: Iatrogenic Hypothyroidism (IH).Fixed-dose regimens often exceed the minimal therapeutic requirement, exposing normal thyroid remnants to unnecessary radiation. Reported IH rates vary widely—from 30 to 80 percent—and represent a major concern in post-treatment management. IH-associated azotemia carries significant prognostic implications. Cats that become hypothyroid and azotemic after treatment have significantly shorter survival times than cats that remain euthyroid or non-azotemic. This underscores the clinical importance of avoiding overtreatment. 1.3 Evidence Supporting Individualized Radioiodine Dosing To mitigate these risks, Peterson and Rishniw (2021) developed a sophisticated, feline-specific dosing algorithm designed to deliver the lowest effective I-131 dose required to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing the likelihood of iatrogenic hypothyroidism and azotemia. Drawing on data from 1,400 hyperthyroid cats, their study established several crucial findings: Median total dose: 1.9 mCi (range 1.0–10.6 mCi)• Considerably lower than historical fixed-dose practices Cure (euthyroid) rate: 74.8 percent, comparable to traditional outcomes Significantly lower complication rates:• 4.1 percent overt hypothyroidism• 17.1 percent subclinical hypothyroidism• Combined rate (~21%) markedly lower than many fixed-dose protocols These outcomes demonstrate that tailored dosing not only achieves therapeutic efficacy but also reduces the risk burden associated with excessive radiation exposure. The Two-Day Algorithmic Protocol The algorithm employs a structured, multiparametric approach based on objective measures of disease severity and biological iodine-handling capacity. Day 1: Initial Composite Dose (80 percent administered) A composite dose score is calculated by integrating three major disease indicators: Serum T4 and T3 concentrations Thyroid tumor volume, measured using thyroid scintigraphy Technetium uptake (TcTU), a marker of functional thyroid activity Only 80 percent of this calculated composite dose is administered initially to avoid overtreatment. Day 2: Uptake-Based Dose Adjustment Approximately 24 hours later, the thyroidal I-131 uptake is measured to determine how effectively the gland concentrates radioiodine. A supplemental dose is then administered as needed. In the study, 1,380 out of 1,400 cats required additional I-131 on Day 2, highlighting the essential role of uptake-based adjustment and the variability in individual glandular kinetics. This two-step method mirrors the logic of precision dosing used in pharmaceutical sciences:deliver enough activity to neutralize the hyperfunctioning tissue, but not so much that normal thyroid function is extinguished or renal sequelae are exacerbated. 2. Radioiodine Pharmacology The therapeutic use of radioiodine (131I) in feline hyperthyroidism rests on a sophisticated interplay between thyroid physiology, nuclear physics, and disciplined radiation-safety practices. The following section synthesizes the core pharmacologic principles, uptake kinetics, veterinary dosimetry, and regulatory safety frameworks that underpin this therapy. 2.1 Mechanism of 131I Radioiodine (131I) exploits the thyroid gland’s unique ability to concentrate iodine for hormone synthesis. Targeting mechanism.The follicular cells of the thyroid actively transport iodine from the bloodstream using the sodium–iodide symporter (NIS). Because the NIS cannot distinguish between stable iodine and 131I, hyperfunctional thyroid tissue accumulates radioiodine to levels that far exceed blood concentrations, often by a factor of 500-fold. In hyperthyroid cats, adenomatous tissue is especially efficient at concentrating 131I. Destructive mechanism.Once incorporated into the gland, 131I decays as a dual-emitter. Its therapeutic activity derives largely from the emission of high-energy beta (β–) particles, which: have a short path length (typically 0.5–2 mm, mean 0.8 mm), generate highly localized cell injury, induce pyknosis, necrosis, and progressive fibrosis over subsequent weeks. This short-range cytotoxicity spares adjacent structures—including the parathyroid glands—substantially reducing the risk of hypoparathyroidism. Selective destruction.In hyperthyroid cats, normal thyroid tissue is usually suppressed by low endogenous TSH levels and therefore takes up minimal 131I. This endogenous suppression optimizes therapeutic selectivity by focusing the radiation burden on the diseased tissue. 2.2 Thyroid Uptake Kinetics Biological and effective half-life.While the physical half-life of ^131I is 8.04 days, the effective half-life in hyperthyroid cats is shorter—approximately 2.3 to 2.54 days—reflecting both physical decay and biological elimination. Renal clearance.Elimination of circulating 131I occurs primarily via renal excretion. Cats with renal disease may retain 131I longer, increasing total radiation burden and necessitating more cautious monitoring. Role of uptake measurement.In individualized radioiodine dosing protocols, 24-hour thyroidal 131I uptake is measured to refine and optimize the total therapeutic dose. This uptake assessment serves as a physiologic indicator of how efficiently the thyroid tissue concentrates radioiodine, allowing clinicians to adjust the administered activity accordingly. Low uptake values signal reduced radioiodine concentration and therefore pose a risk of undertreatment, potentially leading to persistent hyperthyroidism. Conversely, high uptake values increase the likelihood of excessive radiation delivery, elevating the risk of iatrogenic hypothyroidism. As such, measuring thyroidal 131I uptake is pivotal for balancing therapeutic efficacy with preservation of normal endocrine function, and it represents a central component of individualized dosing algorithms. 2.3 Veterinary Dosimetry Considerations Modern veterinary dosimetry emphasizes delivering the lowest effective dose to achieve euthyroidism while minimizing complications such as hypothyroidism and azotemia. The individualized 2-day dosage algorithm used by Peterson and Rishniw (2021)