Breed-related disease: Bichon Frise

The Bichon Frise is often depicted as a French dog. Although the Bichon breed type are originally Spanish, used as sailing dogs, also as herding dogs sometimes, the French developed them into a gentle lap-dog variety. The Bichon type arose from the water dogs, and is descended from the poodle-type dogs and either the Barbet or one of the water spaniel class of breeds. Modern Bichons have developed into four categories: the Bichon Frise or Tenerife, the Maltese, the Bolognese, and the Havanese. These are often treated as separate breeds. A good-size Bichon will stand a shade under a foot tall at the shoulder. The breed’s glory is a white hypoallergenic coat, plush and velvety to the touch, featuring rounded head hair that sets off the large, dark eyes and black leathers of the nose and lips. With its happy-go-lucky attitude, the playful, vivacious, and bouncy Bichon dog delights everyone. It is good with kids and amicable towards pets, other dogs, and strangers. This affectionate, responsive, and sensitive dog also loves to play and be cuddled, but when it is left alone, it may bark excessively. The Bichon dog breed, with a lifespan of about 12 to 15 years, is prone to some serious health problems like: Heart Disease: Bichons are prone to multiple types of heart disease, which can occur both early and later in life. Liver Problems: Your Bichon is more likely than other dogs to have a liver disorder called portosystemic shunt (PSS). Some of the blood supply that should go to the liver goes around it instead, depriving the liver of the blood flow it needs to grow and function properly. If your friend has PSS, his liver cannot remove toxins from his bloodstream effectively. Hip Dysplasia Hip dysplasia is a hereditary condition that prevents the thigh bone from adjusting perfectly to the hip joint. Hip dysplasia is common among Bichon Frise, but it does not affect them all. The dog usually has symptoms of pain and lameness. However, hip dysplasia does not always cause discomfort in the Bichon Frise, but it can develop into arthritis as your dog ages. Incontinence Incontinence can affect your Bichon Frise at any age. If your dog has been previously housetrained, it is important to remember that loss of bladder or bowel control is a physical problem, not a behavioral one. Incontinence is most commonly found in older Bichon Frises, especially females. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bichon_Frise Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bichon_Frise

Breed-related disease: Japanese Bobtail

The Japanese Bobtail is a breed of domestic cat with an unusual bobtail more closely resembling the tail of a rabbit than that of other cats. The variety is native to Japan and Southeast Asia, though it is now found throughout the world. The breed has been known in Japan for centuries, and it frequently appears in traditional folklore and art. Japanese bobtails have two coat types: long and short. The coat can be solid, bi-color, calico, or tabby, but this breed is most commonly white with colored spots, or what some call the van pattern. Both long and short coats are silky smooth, easy to groom, and low-shedding. However, although Japanese bobtails usually shed less than other breeds, they do have shedding seasons in the spring and fall and are not considered hypoallergenic. The Japanese Bobtail is active and intelligent. It’s not unusual to find him splashing his paw in water, carrying toys around, or playing fetch. He is highly curious and loves to explore. Japanese Bobtails are talkative, communicating with a wide range of chirps and meows. Their voices are described as almost songlike. These are outgoing cats who get along well with children and other pets, including dogs, and adjust to travel with ease. They love people and are often seen riding on a shoulder so they can supervise everything going on. We know that because you care so much about your cat, you want to take great care of her. That is why we have summarized the health concerns we will be discussing with you over the life of your Japanese bobtail. Dental Disease: Dental disease is one of the most common chronic problems in pets who don’t have their teeth brushed regularly. Unfortunately, most cats don’t take very good care of their own teeth, and this probably includes your Japanese bobtail. Without extra help and care from you, your cat is likely to develop potentially serious dental problems. Dental disease starts with food residue, which hardens into tartar that builds up on the visible parts of the teeth, and eventually leads to infection of the gums and tooth roots. Protecting your cat against dental disease from the start by removing food residue regularly may help prevent or delay the need for advanced treatment of dental disease. Heart Disease: Cardiomyopathy is the medical term for heart muscle disease, either a primary inherited condition or secondary to other diseases that damage the heart. The most common form, called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, is a thickening of the heart muscle often caused by an overactive thyroid gland. Another example is dilated cardiomyopathy, or DCM, which can be caused by a dietary deficiency of the amino acid taurine. While DCM was a big problem in the past, all major cat food producers now add taurine to cat food, so DCM is rarely seen in cats with high-quality diets today. FLUTD: When your cat urinates outside the litter box, you may be annoyed or furious, especially if your best pair of shoes was the location chosen for the act. But don’t get mad too quickly—in the majority of cases, cats who urinate around the house are sending signals for help. Although true urinary incontinence, the inability to control the bladder muscles, is rare in cats and is usually due to improper nerve function from a spinal defect, most of the time, a cat that is urinating in “naughty” locations is having a problem and is trying to get you to notice. What was once considered to be one urinary syndrome has turned out to be several over years of research, but current terminology gathers these different diseases together under the label of Feline Lower Urinary Tract Diseases, or FLUTD. Renal Failure: Renal failure refers to the inability of the kidneys to properly perform their functions of cleansing waste from the blood and regulating hydration. Kidney disease is extremely common in older cats, but is usually due to exposure to toxins or genetic causes in young cats. Even very young kittens can have renal failure if they have inherited kidney defects, so we recommend screening for kidney problems early, before any anesthesia or surgery, and then regularly throughout life. Severe renal failure is a progressive, fatal disease, but special diets and medications can help cats with kidney disease live longer, fuller lives. Source: https://www.cbvetclinic.com/client-resources/breed-info/japanese-bobtail-longhair/ https://www.cat-lovers-only.com/japanese-bobtail.html Photo crédit: https://www.petfinder.com/cat-breeds/japanese-bobtail/

Generalized Alopecia with Vasculitis-Like Changes in a Dog with Babesiosis- Abstract Tasaki Y, Miura N, Iyori K, Nishifuji K, Endo Y, Momoi Y. J

Source: Vet Med Sci. 2013 Oct;75(10):1367-9. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0482. A 12-year-old, intact female Satsuma dog was referred to the Kagoshima University Veterinary Teaching Hospital due to skin lesions. Clinical symptoms include erythema, crusts and desquamation on the truck, papules and erosions in the pinnae, and multiple areas of skin necrosis on the right forelimb. Treatment with systemic antibiotics and prednisolone did not improve the observed symptoms. The dog also had progressive anemia. Babesia gibsoni was detected in the blood via PCR during its second visit, and the dog was treated with antiprotozoal agents. Though the cutaneous lesions and anemia improved, skin lesions relapsed after the treatment was discontinued. Histopathological examination of skin biopsies revealed findings suggestive of early leukocytoclastic vasculitis or ischemic vasculopathy… Fig. 1. A–D: Appearance of the dog on initial presentation. A: Alopecia, scales and desquamation in the lumbar area. B: Alopecia and erythema on the trunk. C: Erosion and crusts in the pinnae. D: Cutaneous necrosis on the right forelimb. E, F: Appearance during remission after approximately 2 months of antiprotozoal therapy. E: Alopecia and other skin lesions on the trunk are improved, and the hair color changed from light brown to dark brown. F: Erosion and crusts disappear in the pinnae. Fig. 2. Histopathological sections of affected skin. A: Lower magnification showing perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells in the middle portion of dermis. Edema and intense extravasation are seen in the superficial dermis. B: Higher magnification of A showing infiltration of neutrophils into the vessel walls and perivascular area, and fibrin deposition adjacent to the blood vessels.

Cortisol: A Short Review

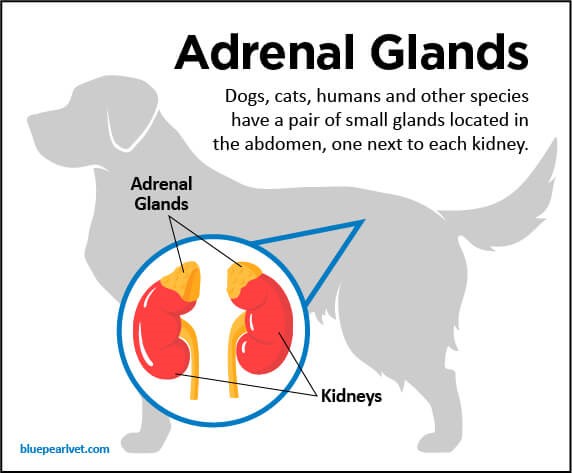

Maigan Espinili Maruquin The well- being of animal can be monitored from stress levels, which is related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis activity (Möstl and Palme 2002, Salaberger, Millard et al. 2016). Elevation of glucocorticoid concentrations are observed in stressful situations (Salaberger, Millard et al. 2016). https://bluepearlvet.com/medical-articles-for-pet-owners/addisons-disease-in-dogs/ Fig. 01. Location of Adrenal glands which produces glucocorticoids Cortisol is known to play an important role in the interconnected responses on physiological, behavioral, and developmental functions (Bennett and Hayssen 2010). As an adrenal glucocorticoid, acute stress response result to rapid release of glucose from energy stores, suppresses inflammation, and promotes immune cell proliferation (Sapolsky, Romero et al. 2000, Charmandari, Tsigos et al. 2005, Mack and Fokidis 2017). Although measuring cortisol used to require significant disruption in behavior, different non- invasive sample collection methods for cortisol is now being used (Bennett and Hayssen 2010). Cortisol Concentration at Different Tissues In humans, salivary cortisol concentration for measurement is popular due to its straightforwardness and minimal invasive effect, including the fact that the storage is easy (Chen, Cintrón et al. 1992, Wenger-Riggenbach, Boretti et al. 2010). For healthy dogs, cortisol is unbound and passively diffuses from blood to saliva (Kirschbaum, C., et al, 1992) (Vincent and Michell 1992, Cobb, Iskandarani et al. 2016). Within 5 minutes, concentration of free cortisol in saliva and plasma sets at an equilibrium (Tunn, Möllmann et al. 1992, Wenger-Riggenbach, Boretti et al. 2010). Although blood and saliva can provide immediate view of cortisol concentrations, blood collection can be stressful, causing elevated concentrations. On the other hand, saliva absorption materials cause inconsistent results (Dreschel and Granger 2009, Bennett and Hayssen 2010). Cortisol concentrations can be measured for a short time in urine and fecal samples (Bennett and Hayssen 2010). In urine, maximum concentration can be reached at approximately 3 hours (Rooney, Gaines et al. 2007, Bennett and Hayssen 2010) and longer in fecal samples (Bennett and Hayssen 2010). Aside from daily fluctuation of cortisol concentrations in saliva, blood, and urine (van Vonderen, Kooistra et al. 1998), it can also be influenced by any stress of the animal (Kobelt, Hemsworth et al. 2003, Mack and Fokidis 2017). A lot of keratinized tissues contain glucocorticoids (Mack and Fokidis 2017). Concentration in the hair provides a long- term information on glucocorticoid production compared to the concentrations during sample collection (Ouschan, Kuchar et al. 2013). However, based on the effects of hair sampling, analysis of long-term cortisol secretion may be complicated (Mack and Fokidis 2017). Hair may also serve as cortisol storage area, however, validation for every species may be required due to difference in cortisol rhythms, secretions and stress response (Bennett and Hayssen 2010). On the other hand, a study was conducted using dog nails to assess cortisol concentration, wherein nail accumulates cortisol passively from the bloodstream (Mack and Fokidis 2017). Hyperadrenocorticism and Hypoadrenocorticism The chronic overexposure to glucocorticoids like cortisol can result to a complex physical and biochemical changes, referred to as hyperadrenocorticism (HAC) (Ouschan, Kuchar et al. 2013). Clinical signs of an affected dog show polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, pot-bellied appearance and typical skin and hair changes (Ouschan, Kuchar et al. 2013) (Feldman EC & Nelson RW, 2004). A tumor in the pituitary gland is usually the cause of this disease, wherein it secretes adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and stimulates adrenal glands, resulting to glucocorticoids production (Ouschan, Kuchar et al. 2013). For humans, diagnosis of hypercortisolism and hypocortisolism through the late-night and morning salivary cortisol concentrations is the established screening test (Viardot, Huber et al. 2005, Nieman, Biller et al. 2008, Restituto, Galofré et al. 2008, Wenger-Riggenbach, Boretti et al. 2010). On the other hand, glucocorticoid deficiency is termed to as hypoadrenocorticism (Peterson, Kintzer et al. 1996), wherein, primary adrenal gland failure is the cause of most cases in dogs (Peterson, Kintzer et al. 1996, Gold, Langlois et al. 2016) (Scott-Moncrieff JC, 2010). Due to general and non- specific clinicopathologic signs, it is confused with primary gastrointestinal, renal, or cardiovascular disease. On-time and accurate diagnosis is important because it is a life-threatening disease if it goes without appropriate treatment (Gold, Langlois et al. 2016). References: Addison’s Disease in Dogs Scott-Moncrieff JC. Hypoadrenocorticism. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 7th ed. volume 2. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2010:1847–1857. Feldman EC, Nelson RW. Canine hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing′s syndrome). In: Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction. 3rd edn. St Louis: Saunders, 2004; 252–357. Kirschbaum C, Read GF, Hellhammer D. Assessment of hormones and drugs in saliva in biobehavioral research. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber; 1992. p. 19–32. Bennett, A. and V. Hayssen (2010). “Measuring cortisol in hair and saliva from dogs: coat color and pigment differences.” Domestic Animal Endocrinology 39(3): 171-180. Charmandari, E., C. Tsigos and G. Chrousos (2005). “ENDOCRINOLOGY OF THE STRESS RESPONSE.” Annual Review of Physiology 67(1): 259-284. Chen, Y. M., N. M. Cintrón and P. A. Whitson (1992). “Long-term storage of salivary cortisol samples at room temperature.” Clin Chem 38(2): 304. Cobb, M. L., K. Iskandarani, V. M. Chinchilli and N. A. Dreschel (2016). “A systematic review and meta-analysis of salivary cortisol measurement in domestic canines.” Domestic Animal Endocrinology 57: 31-42. Dreschel, N. A. and D. A. Granger (2009). “Methods of collection for salivary cortisol measurement in dogs.” Horm Behav 55(1): 163-168. Gold, A. J., D. K. Langlois and K. R. Refsal (2016). “Evaluation of Basal Serum or Plasma Cortisol Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Hypoadrenocorticism in Dogs.” Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 30(6): 1798-1805. Kobelt, A. J., P. H. Hemsworth, J. L. Barnett and K. L. Butler (2003). “Sources of sampling variation in saliva cortisol in dogs.” Res Vet Sci 75(2): 157-161. Mack, Z. and H. B. Fokidis (2017). “A novel method for assessing chronic cortisol concentrations in dogs using the nail as a source.” Domestic Animal Endocrinology 59: 53-57. Möstl, E. and R. Palme (2002). “Hormones as indicators of stress.” Domestic Animal Endocrinology 23(1): 67-74. Nieman, L. K., B. M. Biller, J. W. Findling, J. Newell-Price, M. O. Savage, P. M. Stewart and V. M.