Breed-related disease: Birman Cat

The origin of the Birman cat is not well known, with much of his history tied in with cultural legends, While there is no clear record of the origin of Birman cats, one pair was taken to France around 1919, from which the breed became established in the western world. However, Birman cats were almost wiped out as a breed during World War II and were heavily outcrossed with long-hair breeds (mainly Persians) and also Siamese lines to rebuild the breed. By the early 1950s, pure Birman cat litters were once again being produced. The restored breed was recognized in Britain in 1965. The Birman, also known as the “Sacred Cat of Burma” is semi-longhaired with darker coloring to the points, face, legs, ears, and tail, and a pale toning body color. It is a largish cat with a thickset body and short legs.The Birman cat has blue eyes and four pure white feet. The front gloves covering only the feet, but the rear socks are longer. The head is broad and rounded with medium-size ears. They come in lots of different colors. The Birman is a calm, affectionate cat who loves to be around people and can adapt to any type of home. He likes to play chase with other pets, taking turns being the chaser and the one being pursued. Birmans make friends with kids, dogs , and other cats. In fact, unlike most felines, they don’t especially like being the “only pet,” so you may want to get your Birman a companion – he won’t care if it’s another Birman, a different breed of cat, or even a dog. Birmans aren’t demanding of your attention, but they’ll definitely let you know when they need a head scratch or some petting. Then they’ll go about their business until it’s time for you to adore them again. You should also keep your Birman entertained with interactive toys that require him to do some thinking and moving to pop out treats or kibble. Here we gathered for you the most common Genetic Predispositions about Birmans, let’s get started: Luckily, Birman cats are relatively healthy and aren’t predisposed to any major conditions. But, the common health concerns that plague other cats are things to look out for. These include obesity, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and kidney disease. Obesity Because of the hefty weight of these kitties, they may be more prone to feline obesity, which can cause a myriad of other health concerns. Just like humans, it’s important to do everything you can to help your kitty maintain a healthy weight. By limiting their food intake, exercising them regularly, and keeping up with regular vet visits, you can completely prevent this condition. It is up to the owner of Birmans to make sure they stay at a healthy weight. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) Not specific to Birman cats, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common heart condition in cats. It causes the walls of the heart muscle to thicken and can cause the heart to increase in size. This is a genetically inherited condition, and breeders can check their lines for this condition. HCM is something to always be aware of, even if your kitty has a clean bill of health. HCM ranges in severity and can be treated with supplements, herbs, and other natural remedies. Kidney Disease Some lines of modern Birman cats may descend from Persians, who are also prone to kidney disease. Because of this, Birmans may be more susceptible. Sources: https://canna-pet.com/breed/birman-cat/ https://www.purina.co.uk/cats/cat-breeds/library/birman Photo credit: https://prettylitter.com/blogs/prettylitter-blog/birman-cats-101-pretty-litter https://cats.lovetoknow.com/Birman_Cats

Breed-related disease: French bulldog

The “bouldogge Francais,” as he is known in his adopted home country of France, actually originated in England, in the city of Nottingham. Small bulldogs were popular pets with the local lace workers, keeping them company and ridding their workrooms of rats. After the industrial revolution, lacemaking became mechanized and many of the lace workers lost their jobs. Some of them moved to France, where their skills were in demand, and of course they took their beloved dogs with them. The dogs were equally popular with French shopkeepers and eventually took on the name of their new country. The little dogs became popular in the French countryside where lace makers settled. Over a span of decades, the toy Bulldogs were crossed with other breeds, perhaps terriers and Pugs, and, along the way, developed their now-famous bat ears. They were given the name Bouledogue Français. French bulldogs (Frenchies) are known for their quiet attentiveness. They follow their people around from room to room without making a nuisance of themselves. When they want your attention, they’ll tap you with a paw. This is a highly alert breed that barks judiciously. If a Frenchie barks, you should check it out. What’s not to like? Frenchies can be stubborn about any kind of training. Motivate them with gentle, positive techniques. When you find the right reward, they can learn quickly, although you will find that they like to put their own spin on tricks or commands, especially when they have an audience. All dogs have the potential to develop genetic health problems, just as all people have the potential to inherit a particular disease, The French Bulldog is prone to certain health problems. Here’s a brief rundown on what you should know. Ear Infections French Bulldogs have very narrow ear canals, and for this reason, are very vulnerable to ear infections. They are also susceptible to allergies which can give them these infections. Ear glands swell up to resist infections and produce more wax than normal. This leads to an overproduction of ear tissue, making the canal ever narrower, and inflamed. In severe cases the eardrum can rupture, causing your pooch a lot of pain! Look out for excessive ear scratching and redness inside the ear as warnings of this problem Diarrhea Stomach upsets are very common in Frenchies, so monitoring their diet is a must. Consistent bouts of diarrhea can be caused by parasites, viruses, or E. coli, all of which Frenchies are very sensitive to. Take note of their stools if they are wet, runny, or tarry, smell foul, or if you see blood in the stools. These are all signs of a serious digestion problem. Other tell-tale signs are your dog losing weight, losing their appetite, vomiting or having a fever. Conjunctivitis Again, due to the genetic makeup of French Bulldogs, they are at a high risk of suffering from conjunctivitis. This is because they are a short-nosed (brachycephalic) breed. It’s usually caused by bacterial and viral infections or allergic reactions to substances. Watch out for your Frenchie having pink or red eyes, if they start blinking more than usual, or have mucus, pus or discharge leaking from their eyes. Skin Problems – Skin Fold Dermatitis Due to French Bulldogs folded facial skin around their muzzle and nose, this can lead to dermatitis. It can also occur in other areas of their bodies that are folded, like armpits, necks, and crotches. Signs of this problem include itching, biting and scratching of the area, and redness and sores on the affected skin. Keeping skin folds dry and clean can prevent dermatitis from occurring. Skin Problems – Pyoderma (bacterial skin infection) Another common skin problem is bacterial skin infections. This occurs when your dog has a cut or scratch that becomes infected. Again, look out for itching, red skin, pus, and loss of hair around the cut. It’s another health problem that comes from having skin folds. Breathing Problems – URT Infection As a short-nosed breed, French Bulldogs are very at-risk of upper respiratory tract infections. These will usually happen to every bulldog at least once in their lives and are infectious, so will occur if your dog spends more time with other canines. Symptoms are a lot like human colds: nasal congestion, coughing, and lethargy. Breathing Problems – Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) Sadly, many French Bulldogs are also at a high risk of BOAS due to their squashed faces and short snouts. This can lead to shortness of breath, trouble breathing, sleeping difficulties, and heat intolerance. You’ll notice this problem occurring during exercise and in warmer temperatures. Mobility Issues in French Bulldogs There is a range of conditions that can affect the Frenchie’s mobility. Ranging from congenital conditions, injuries, and degenerative disease. Conditions such as hip dysplasia and luxating patellas can be caused by genetic or caused by old injuries. Other conditions affecting Frenchies include IVDD, spinal disc issues, and degenerative myelopathy (DM). Sources: https://www.handicappedpets.com/blog/common-health-problems-in-frenchies/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/french-bulldog#health Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Bulldog American kennel Club

Bartonella henselae: An Infectious Pathogen among Cats

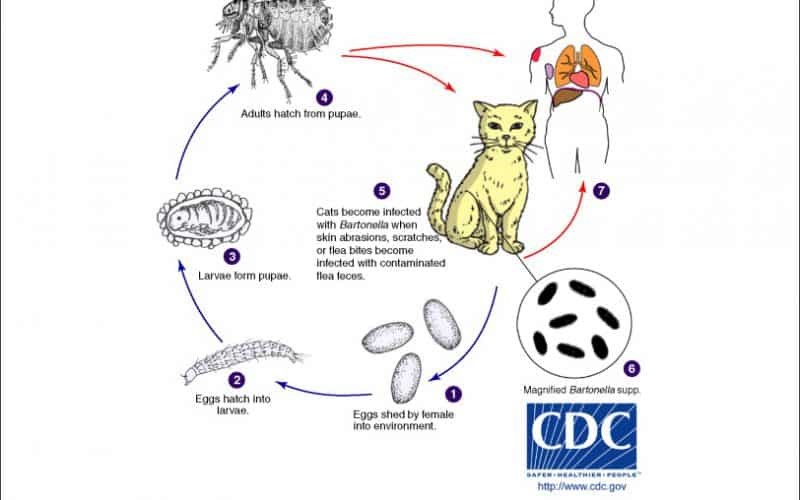

Table of Contents Maigan Espinili Maruquin 1. Introduction Overview of Bartonella henselae as a Significant Feline and Zoonotic Pathogen Bartonella henselae is a small, fastidious, Gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacterium with a global distribution. It exhibits a marked tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes, enabling the establishment of chronic, relapsing bacteremia that may persist for months or even years in infected hosts. Domestic cats are the primary mammalian reservoir and represent the principal source of zoonotic transmission to humans. Kittens and feral cats typically harbor higher bacterial loads, although subclinical infection is widespread across the global feline population. Reported bacteremia prevalence in apparently healthy cats ranges from 8% to 56%, depending on geographic region and flea exposure. The primary competent vector for B. henselae is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), within which the organism replicates in the flea gut and is excreted in flea feces (commonly referred to as flea dirt). These contaminated feces can remain infectious in the environment for at least nine days, facilitating indirect transmission. Importance in Companion Animal Medicine and Public Health From a companion animal medicine perspective, B. henselae is clinically significant because most infected cats function as asymptomatic carriers, silently sustaining zoonotic risk. Nevertheless, increasing evidence links B. henselae infection to sporadic but severe feline disease manifestations, including endocarditis, myocarditis, and ocular inflammatory conditions such as uveitis. In dogs, which are considered accidental hosts, bartonellosis is often more pathogenic and has been strongly associated with culture-negative endocarditis and granulomatous inflammatory disease. In public health, B. henselae is best known as the primary etiological agent of Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) in humans. Transmission most commonly occurs when cat claws or oral cavities become contaminated with infected flea feces, which are then inoculated into human skin through a scratch or bite. Immunocompetent individuals typically develop a self-limiting illness characterized by regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and a papule at the site of inoculation. Immunocompromised individuals, including those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients, are at risk for severe and potentially fatal complications, such as bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis, encephalitis, and endocarditis, reflecting the organism’s vasoproliferative potential. Scope of the Review and Relevance to Clinical Practice A clear understanding of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and persistence mechanisms of B. henselae is essential for effective clinical management and disease prevention. Diagnosis remains particularly challenging, as the organism is highly fastidious and slow-growing, frequently resulting in false-negative blood culture findings and so-called “culture-negative” infections. Although molecular assays such as PCR and serological testing are widely employed, interpretation is complicated by intermittent bacteremia and the high background seroprevalence among healthy cats. In clinical practice, adoption of a One Health framework is critical. Veterinarians play a central role in mitigating zoonotic risk through owner education, emphasizing strict, year-round flea control, appropriate hygiene, and cautious interaction with cats, especially in households containing immunocompromised individuals. Management is further complicated by the absence of a standardized antimicrobial protocol capable of reliably achieving complete bacteriological clearance in feline hosts. To conceptualize its biological behavior, B. henselae may be likened to a “stealthy hitchhiker.” By residing within erythrocytes and vascular endothelium, the organism evades immune surveillance, periodically re-emerging only to secure transmission via a passing flea. 2. Characteristics and Epidemiology 2.1 Taxonomy and Microbiological Characteristics The genus Bartonella comprises small, thin, fastidious, and pleomorphic Gram-negative bacilli. These organisms are facultative intracellular pathogens with a highly specialized biological niche characterized by a pronounced tropism for endothelial cells and erythrocytes (red blood cells). Following host entry, Bartonella spp. proliferate within membrane-bound vacuoles, often referred to as invasomes, inside vascular endothelial cells. Periodic release into the bloodstream allows subsequent invasion of erythrocytes, within which the bacteria may persist until cellular senescence or destruction occurs (Cunningham and Koehler 2000; LeBoit 1997). Transmission is predominantly arthropod-borne, involving vectors such as fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), ticks, lice, and sand flies. Although Bartonella species have been isolated from a wide range of mammalian hosts, including rodents, rabbits, canids, and ruminants, domestic and feral cats represent the principal mammalian reservoir for the most epidemiologically and clinically significant zoonotic species, particularly B. henselae (Chomel et al., 1996; Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Guptill, 2012). 2.2 Global Distribution and Seroprevalence Bartonella species exhibit a global distribution, although prevalence varies markedly according to environmental and ecological conditions. In European feline populations, reported antibody prevalence ranges from 8% to 53% (Pennisi, Marsilio et al., 2013; Zangwill, 2013), while global serological evidence of exposure in cats spans approximately 5% to 80% (Guptill, 2012). The epidemiology of Bartonella infection is strongly influenced by geography, climate, and flea density. The highest prevalence rates are consistently observed in warm, humid temperate and tropical regions, where environmental conditions favor the survival and propagation of C. felis. In contrast, in colder climates, such as Norway, Bartonella infection in cats is reported to be rare or virtually absent, reflecting the limited persistence of flea vectors under such conditions. 2.3 Species Diversity and Genotypes Although 22 to 38 Bartonella species have been described to date, Bartonella henselae remains the most frequently detected species in both domestic cats and humans. Feline populations may also harbor Bartonella clarridgeiae, identified in approximately 10% of infected cats, while B. koehlerae is detected far less commonly (Guptill, 2012). Considerable regional variation exists among B. henselae genotypes, which are broadly classified into Houston-1 (Type I) and Marseille (Type II) strains. Type II (Marseille) predominates among feline populations in the western United States, western continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Type I (Houston-1) is the dominant genotype in Asia, including Japan and the Philippines, and is most frequently isolated from human clinical cases worldwide, even in regions where Type II strains are more prevalent among cats. Beyond domestic cats, Bartonella infections have been documented in non-domestic felids, including African lions, cheetahs, and various neotropical wild cat species, underscoring the broad ecological adaptability of the genus (Guptill, 2012). To conceptualize its ecological behavior, Bartonella may be viewed as a “weather-dependent squatter.” It establishes itself most successfully in warm, densely populated environments rich in flea vectors,

Feline Pancreatic Lipase (fPL)

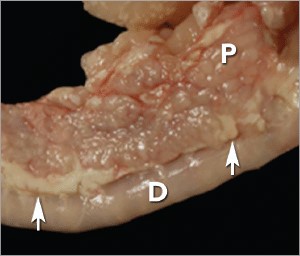

Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Pancreatitis appears to be a common disease in cats,1 yet it remains frustratingly difficult to establish a clinical diagnosis with certainty. Clinicians must rely on a combination of compatible clinical findings, serum feline pancreatic lipase (fPL) measurement, and ultrasonographic changes in the pancreas to make an antemortem diagnosis, yet each of these 3 components has limitations. Acute Versus Chronic Pancreatitis Acute pancreatitis is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation, with variable amounts of pancreatic acinar cell and peripancreatic fat necrosis (Figure 1).1 Evidence is mounting that chronic pancreatitis is more common than the acute form, but sonographic and other clinical findings overlap considerably between the 2 forms of disease.1-3 Diagnostic Challenges Use of histopathology as the gold standard for diagnosis has recently been questioned because of the potential for histologic ambiguity.3,4 A seminal paper exploring the prevalence and distribution of feline pancreatic pathologic abnormalities reported that 45% of cats that were apparently healthy at time of death had histologic evidence of pancreatitis.1 The 41 cats in this group included cats with no history of disease that died of trauma, and cats from clinical studies that did not undergo any treatment (control animals). Conversely, multifocal distribution of inflammatory lesions was common in this study, raising the concern that lesions could be missed on biopsy or even necropsy. Prevalence Such considerations help explain the wide range in the reported prevalence of feline pancreatitis, from 0.6% to 67%.3 The prevalence of clinically relevant pancreatitis undoubtedly lies somewhere in between, with acute and chronic pancreatitis suggested to represent opposite points on a disease continuum.2 FIGURE 1. Duodenum (D) and duodenal limb of the pancreas (P) in a cat with acute pancreatitis and necrosis; well-demarcated areas of necrosis are present at the periphery of the pancreas in the peripancreatic adipose tissue(arrows). Courtesy Dr. Arno Wuenschmann, Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory Risk factors No age, sex, or breed predisposition has been recognized in cats with acute pancreatitis, and no relationship has been established with body condition score.3-5 Cats over a wide age range, from kittens to geriatric cats, are affected; cats older than 7 years predominate. In most cases, an underlying cause or instigating event cannot be determined, leading to classification as idiopathic.3 Abdominal trauma, sometimes from high-rise syndrome, is an uncommon cause that is readily identified from the history.6 The pancreas is sensitive to hypotension and ischemia; every effort must be taken to avoid hypotensive episodes under anesthesia. Comorbidities In cats with acute pancreatitis, the frequency of concurrent diseases is as high as 83% (Table 1).2 Pancreatitis complicates the management of some diabetic cats and may induce, for example, diabetic ketoacidosis.7 Anorexia attributable to pancreatitis can be the precipitating cause of hepatic lipidosis.8 The role of intercurrent inflammation in the biliary tract or intestine (also called triaditis) in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis is still uncertain. Roles of Bacteria In one study, culture-independent methods to identify bacteria in sections of the pancreas from cats with pancreatitis detected bacteria in 35% of cases.9 This report renewed speculation about the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis, and the potential role that the common insertion of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct into the duodenal papilla may play in facilitating reflux of enteric bacteria into the “common channel” in cats. Awareness of triaditis may affect the diagnostic evaluation of individual patients. Table 1. Clinical Data from 95 Cats with Acute Pancreatitis (1976—1998; 59% Mortality Rate) & 89 Cats Diagnosed with Acute Pancreatitis (2004—2011; 16% Mortality Rate) PARAMETER HISTORICAL DATA* CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† SURVIVING CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† Number of Cats 95 89 75 ALP elevation 50% 23% 18% ALT elevation 68% 41% 36% Apparent abdominal pain 25% 30% 32% Cholangitis NA 12% 11% Concurrent disease diagnosed NA 69% 68% Dehydration 92% 37% 42% Diabetic ketoacidosis NA 8% 5% Diabetes mellitus NA 11% 12% Fever 7%‡ 26% 11% GGT elevation NA 21% 18% Hepatic lipidosis NA 20% 19% Hyperbilirubinemia 64% 45% 53% Icterus 64% 6% 6% Vomiting 35%—52% 35% 36% ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; GGT = gamma glutamyl transferase; NA = not available * Summarized from 4 published case series; a total of 56 cats had acute pancreatitis diagnosed at necropsy and 3 by pancreatic biopsy5,8,10,11 † Data obtained from reference12 ‡ 68% of cats were hypothermic DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION Many cats with pancreatitis have vague, nonspecific clinical signs, which make diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical signs related to common comorbidities, such as anorexia, lethargy, and vomiting, may overlap with, or initially mask, the signs associated with pancreatic disease. Early publications on the clinical characteristics of acute pancreatitis required necropsy as an inclusion criterion, presumably skewing the spectrum of severity of the reported cases.5,8,10,11 Cats with chronic pancreatitis were excluded from these reports. Clinical Findings Table 1 lists common clinical findings in cats from necropsy-based reports and a recent series of 89 cats with acute pancreatitis studied by the authors.12 Note the lower prevalence of most clinical findings in the cats diagnosed clinically rather than from necropsy records. In our evaluation of affected cats, 17% exhibited no signs aside from lethargy and 62% were anorexic. Vomiting occurs inconsistently (35%—52% of cats). Abdominal pain is detected in a minority of cases even when the index of suspicion of pancreatitis is high. About ¼ of cats with pancreatitis have a palpable abdominal mass that may be misdiagnosed as a lesion of another intra-abdominal structure. Laboratory Analyses Hematologic abnormalities in cats with acute pancreatitis are nonspecific; findings may include nonregenerative anemia, hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, or leukopenia. Serum biochemical profile results vary (Table 1). In our acute pancreatitis case series, 33% of cats had no abnormalities in their chemistry results at presentation.12 Serum cholesterol concentrations may be high in up to 72% of cases. Some cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with severe clinical syndromes, such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure, that influence some serum parameters, such as albumin, liver enzymes, and coagulation tests. Plasma ionized calcium concentration may be low, and has

Concurrent with T-zone lymphoma and high-grade gastrointestinal cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma in a dog

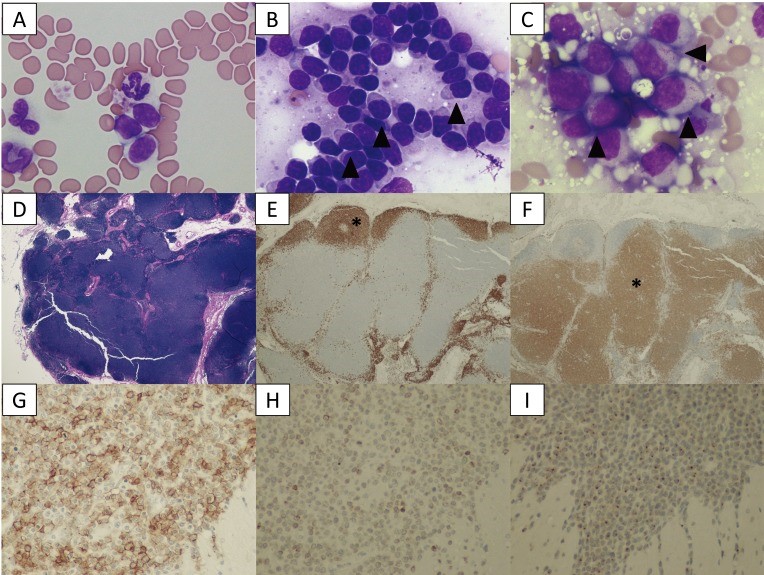

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5402196/ A 9-year-old, spayed female Golden Retriever dog showed lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy, secondary to suspected chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Small-to-intermediate lymphocytes were observed from the cytological examination of the right popliteal lymph node via a fine-needle aspirate. The dog was suspected to have a low-grade lymphoma based on the finding of cytology. Also, ultrasonography reveled thickened lesions in the stomach and small intestine. Histopathology of the popliteal lymph node and small intestine revealed a simultaneous presence of T-zone lymphoma (TZL) and high-grade gastrointestinal (GI) cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. PCR for antigen receptor rearrangements assay suggested that both lymphomas, though both originated in the T-cells, derived from different genes. The dog died 15 days after diagnosis, despite chemotherapy. Fig. 1. A–C: Cytological images on day 1. (A) Peripheral blood smear. Increased numbers of small lymphocytes. (B) Cytology of the popliteal lymph node biopsy. Most lymphocytes are small-to-intermediate, mature lymphocytes. Some lymphocytes show a “hand mirror” type of cytoplasmic extension (arrowhead) (Wright-Giemsa stain, × 400). (C) Slide preparation of tissue from the small intestine. The lymphocytes are intermediate-to-large, immature cells, and some display azurophilic granules in the cytoplasm (LGLs, arrowhead). D–F: Histological images of popliteal lymph node tissue. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. (E) The lymphocytes with fading follicular structures are CD20 positive (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD20, a hematoxylin counterstain. (F) The nodal capsule (CD3 positive) is thinned without the involvement of the perinodal tissue (asterisk). Immunolabeling with anti-CD3, hematoxylin counterstain. G–I: Histological images of the intestinal tissue. All lymphocytes are positive for CD20 (G), CD3 (H) and granzyme B (I). Fig. 2. (A) Transverse ultrasound image on day 1 showing a thickened intestinal wall (approximately 9.0 mm, arrowhead). (B) Post-contrast transverse CT image on day 2 also showing a thickened intestinal wall (arrowheads). The intrathoracic and abdominal lymph nodes are enlarged. Fig. 3. PARR analysis. (A) The peripheral blood sample shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. (B) The intestinal tissue sample also shows TCRγ gene rearrangement. The two tumors demonstrate clonal expansions from different primers.