Breed-related disease: Russian Blue Cat

Although the Russian blue’s exact origins are not known for certain, but the Russian Blue cat was originally known as the Archangel Cat because it was said to have arrived in Europe aboard ships from the Russian port of that name (Arkhangel’sk). It has also been known as the Spanish Cat and the Maltese cat, particularly in the US where the latter name persisted until the beginning of the century. The cat was favored by royals and preferred by the Russian czars. The Russian Blue cat is medium to large in size with an elegant, graceful body and long, slim legs. The cat walks as if on tip-toes. The head is wedged shaped with prominent whisker pads and large ears. The vivid green eyes are set wide apart and are almond shaped. The coat is double with a very dense undercoat and feels fine, short and soft. In texture the coat of the Russian Blue cat is very different from any other breed and is the truest measure of the breed. Although named the Russian Blue, black and white Russian cats do sometimes appear. In the most popular blue variety, the coat colour is a clear even blue with a silvery sheen. The Russian blue is a sweet-tempered, loyal cat who will follow her owner everywhere, so don’t be surprised if she greets you at the front door! While she has a tendency to attach to one pet parent in particular, she demonstrates affection with her whole family and demands it in return. It’s said that Russian blues train their owners rather than the owners training them, a legend that’s been proven true time and again. They are very social creatures but also enjoy alone time and will actively seek a quiet, private nook in which to sleep. They don’t mind too much if you’re away at work all day, but they do require a lot of playtime when you are home. Russian blues tend to shy away from visitors and may hide during large gatherings. As we know you care for your pet, below, we listed the few of the most common diseases in the animal Weight related problems. The Russian Blue cat really enjoys its food and it may continue to eat as much as it chooses. So, it’s best to limit the amount of food that the cat enjoys to ensure a healthy diet and to combat any weight related illnesses . Progressive retinal atrophy refers to a family of eye conditions which cause the retina’s gradual deterioration. Night vision is lost in the early stages of the disease, and day vision is lost as the disease progresses. Many cats adapt to the loss of vision well, as long as their environment stays the same. Polycystic kidney disease. PKD is a condition that is inherited and symptoms can start to show at a young age. Polycystic Kidney Disease causes cysts of fluid to form in the kidneys, obstructing them from functioning properly. It can cause chronic renal failure if not detected . Look for symptoms like poor appetite, vomiting, drinking excessively, frequent urination, lethargy and depression. Ultrasounds are the best way to diagnose the disease, and some cats can be treated with diet, medication and hormone therapy. Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is a disease that can affect the bladder and urethra of cats. Cats with FLUTD present with pain and have difficulty urinating. They also urinate more often and blood may be visible in the urine. Cats may lick their genital area excessively and sometimes randomly urinate around the house. These symptoms may re-occur through a cat’s life so it’s best to discuss things with a vet. Source: https://www.purina.co.uk/cats/cat-breeds/library/russian-blue https://bowwowinsurance.com.au/cats/cat-breeds/russian-blue/ Picture credit 1 Picture credit 2

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog

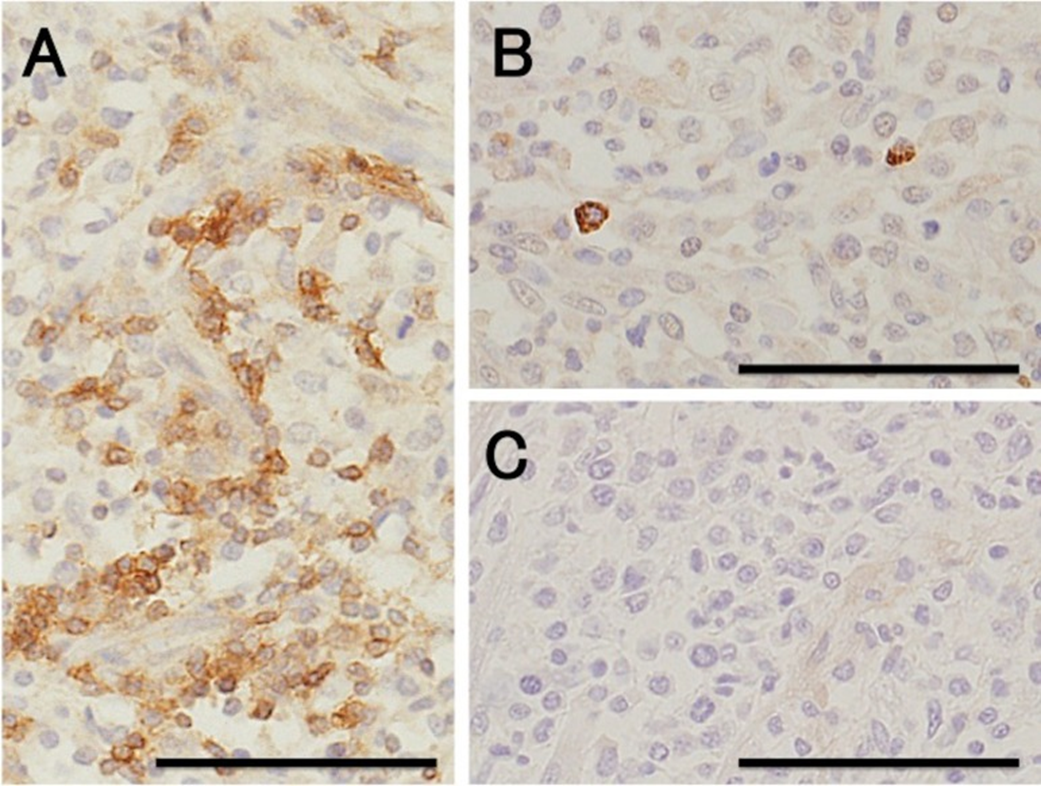

Case study: Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog Robert Lo, Ph.D, D.V.M Original: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6261812/ Canine lymphoma usually appears in multicentric, alimentary, mediastinal, and cutaneous forms, but rarely affects only heart. This case reports a uncommon primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) of a 10-week-old miniature dachshund. The dog clinically showed acute onset of weakness. Electrocardiography indicated sustained ventricular tachycardia, and thoracic and abdominal radiography revealed pleural and peritoneal effusion. Echocardiography revealed severely hypokinetic left and right ventricles. After failure of treatment, the dog died about 1 hr after admission and underwent autopsy. Gross examination of a longitudinal section through the entire heart revealed poorly demarcated focal or patchy areas of grayish-white tissue infiltrating extensively into the myocardium. Histologically, these lesions were consistent with infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the diagnosis of PCL of T-cell origin. There have been no previous reports of such young dogs with PCL. Fig. 1. Six lead electrocardiographic tracings from the 10-week-old dog, showing monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, rate 360 beats per minute, almost regular (bipolar standard limb leads; 50 mm/sec). Fig. 2. Formalin-fixed heart transected along the long axis, showing extensive infiltration of grayish-white neoplastic tissue into the myocardium of the entire heart. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. Scale: 1 mm. Fig. 3. (A) Microscopic section taken from the ventricular septum, showing marked infiltrative proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells in the myocardium. Sheets of neoplastic round cells separate individual muscle fibers. HE. Bar: 50 µm. (B) The outlined square area in A is shown at higher magnification. HE. Bar: 20 µm. Fig. 4. Immunohistochemical labeling of the neoplastic lymphoid cells. Hematoxylin counterstain. Bar: 50 µm. (A) A large number of neoplastic cells stain positively for CD3. (B) Fewer neoplastic cells stain positively for CD79α. (C) All the neoplastic cells are negative for CD20.