Breed-related disease: Bull Terrier

John K. Rosembert Descended from the extinct old English bulldog and Manchester terrier, the bull terrier was originally bred to help control vermin and to fight in the blood sports of bull and bear baiting. Today’s iteration looks as different as he behaves. With the most recognizable feature is its head, described as ‘egg-shaped head’, when viewed from the front; the top of the skull is almost flat. The profile curves gently downwards from the top of the skull to the tip of the nose, which is black and bent downwards at the tip, with well-developed nostrils. The lower jaw is deep and strong. The unique triangular eyes are small, dark, and deep-set, it is a very recognizable breed. The Bull Terrier is a people dog, plain and simple. He’s happiest when he’s with his family so he’s a terrible choice for an outdoor dog. However, that isn’t to say he wants to lie adoringly at your feet. He’d much rather you got up and came outside with him, and went on a short stroll of, say, 10 miles. Those excursions might be a lot more fun if he weren’t an infamous leash-tugger with a tendency to go chasing after every dog, cat and squirrel he sees. Be prepared to train him to listen to you – something he’ll have a hard time seeing the value of much of the time. Training isn’t optional with this breed, unless the idea of a dog weighing between 45 and 80 pounds dragging you all over the neighborhood and ignoring every word you say in your own house appeals to you. Train your Bull Terrier from puppyhood on, with an emphasis on consistency, and you’ll have a well-behaved, well-socialized canine family member. Bull terriers can be protective, especially if they think their family is in danger, so be sure to socialize them around strangers and don’t encourage aggressive or guarding behavior. They can also be protective of their own space, toys, and food. This behavior must be caught early and corrected consistently, as it can lead to serious behavior problems. Common Bull Terrier Diseases & Conditions Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment Patella luxation. Affects Bull Terriers quite often and is simply a disorder that causes the dislocation of the kneecap. Heart Defects and Heart Disease. Heart defects in Bull Terriers are also quite common and can include cardiac valves that leak or valves that are too narrow to transport blood in the required amount. These defects can result in heart murmurs or irregular heartbeats. Symptoms to look out for include: coughing, lethargic behavior, excessive weight loss or weight gain and distressed breathing. See a vet for assistance if you are observing any of these signs. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD). PKD affects both the Bull Terrier and the Miniature Bull Terrier. It’s a condition that is inherited and symptoms can start to show at a young age. Polycystic Kidney Disease causes cysts of fluid to form in the kidneys, obstructing them from functioning properly. Look for symptoms like: poor appetite, vomiting, drinking excessively, dry or pale gums and lethargic behavior. Deafness, like any breed, occurs in Bull Terriers and can be detected from as early as four weeks of age. If you believe your Bull Terrier is suffering from a loss of hearing, your vet can perform some tests to determine the situation. https://bowwowinsurance.com.au/dogs/dog-breeds/bull-terrier/ http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/bull-terrier#grooming Photo credit https://animalscontent.blogspot.com/2019/11/bull-terrier.html

Breed-related disease: Bombay cat

The Bombay is one of several breeds created to look like a miniature version of a wild cat. In Bombay’s case, it is the Mini-Me of the Black Panther and does quite a good impersonation indeed. To achieve the breed, breeders took two different paths. In Britain, they crossed Burmese with black domestic cats. In the United States, where the Bombay’s development in the 1950s is generally credited to Nikki Horner of Louisville, Kentucky, the breed was created by crossing sable Burmese with black American Shorthairs. The Bombay is recognized by the Cat Fanciers Association, The International Cat Association, and other cat registries. The Bombay is a medium-sized cat, she feels considerably heavier than she appears. This breed is stocky and somewhat compact but is very muscular with heavy boning. The Bombay is round all over. The head is round, the tips of the ears are round, the eyes, chin, and even the feet are round. The coat of the Bombay is short and glossy. When the coat is in proper condition, its deep black luster looks like patent leather. It has a characteristic walk. their body appears almost to sway when she walks. Again, this walk is reminiscent of the Indian black leopard. The Bombay is extremely friendly. This cat breed needs one-on-one time with his cat parents. It is a cat breed that does not do well alone all day. The Bombay enjoys snuggling up on your lap and can do so for hours. It is not a very independent cat breed. That said, it may develop a Velcro-like attachment to his pet parent. Younger Bombay kittens are active and playful. Senior Bombay cats tend to enjoy watching and are much less active. This cat breed is perfect for either apartment or farm living. They are quiet cats that enjoy interactive play. The Bombay enjoys playing with anything that is lying around and is playful when there is someone to play with. This wonderful cat breed is super soft to cuddle with and is easy to live with. The Bombay needs plenty of love, fun cat toys, and mental stimulation. This cat breed is not very vocal. The Bombay is generally healthy, but some of the problems that affect the breed are as below: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) : is the most common form of heart disease in cats. It causes thickening (hypertrophy) of the heart muscle. An echocardiogram can confirm whether a cat has HCM. Avoid breeders who claim to have HCM-free lines. No one can guarantee that their cats will never develop HCM. Excessive tearing of the eyes : Bombay cats can also suffer from the excessive tearing of the eyes, which can be treated with drops. As with all cats, it’s important to keep an eye on your pet as they get older, which is when they might start to show signs of developing health conditions. Sources: https://www.thesprucepets.com/bombay-breed-profile-551859#characteristics-of-the-bombay-cat http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/bombay#health

Breed-related disease: Doberman

Doberman Pinschers originated in Germany during the late 19th century, mostly bred as guard dogs. Their exact ancestry is unknown, but they’re believed to be a mixture of many dog breeds, including the Rottweiler, Black and Tan Terrier, and German Pinscher. Dobermans are compactly-built dogs—muscular, fast, and powerful—standing between 24 to 28 inches at the shoulder. The body is sleek but substantial and is covered with a glistening coat of black, blue, red, or fawn, with rust markings. These elegant qualities, combined with a noble, wedge-shaped head and an easy, athletic way of moving have earned Dobermans a reputation as royalty in the canine kingdom. A well-conditioned Doberman on patrol will deter all but the most foolish intruder. Doberman’s qualities of intelligence, trainability, and courage have made him capable of performing many different roles, from police or military dog to family protector and friend. The ideal Doberman is energetic, watchful, determined, alert, and obedient, never shy or vicious. That temperament and relationship with people only occur when the Doberman lives closely with his family so that he can build that bond of loyalty for which he is famous. A Doberman who is left out in the backyard alone will never become a loving protector but instead a fearful dog who is aggressive toward everyone, including his own family. The perfect Doberman doesn’t come ready-made from the breeder. Any dog, no matter how nice, can develop obnoxious levels of barking, digging, counter-surfing, and other undesirable behaviors if he is bored, untrained, or unsupervised. And any dog can be a trial to live with during adolescence. Start training your puppy the day you bring him home. Even at eight weeks old, he is capable of soaking up everything you can teach him. Don’t wait until he is 6 months old to begin training or you will have a more headstrong dog to deal with. Doberman are generally healthy, however, like other breeds, they have some problems that occur more frequently than in general dog population, below are some of the most common diseases in Doberman CARDIOMYOPATHY: is a disease of the heart muscle that results in weakened contractions and poor pumping ability. As the disease progresses the heart chambers become enlarged, one or more valves may leak, and signs of congestive heart failure develop. This disease is suspected to be an inherited disease in Dobermans. Research is in progress in several institutions. An echocardiogram of the heart will confirm the disease but WILL not guarantee that the disease will not develop in the future. HIP DYSPLASIA: is inherited. It may vary from slightly poor conformation to malformation of the hip joint allowing complete luxation of the femoral head. Cervical vertebral instability (CVI): commonly called Wobbler’s syndrome. It’s caused by a malformation of the vertebrae within the neck that results in pressure on the spinal cord and leads to weakness and lack of coordination in the hindquarters and sometimes to complete paralysis. Symptoms can be managed to a certain extent in dogs that are not severely affected, and some dogs experience some relief from surgery, but the outcome is far from certain. While CVI is thought to be genetic, there is no screening test for the condition. Dobermans are also prone to the bleeding disorder known as von Willebrand disease, as well as hypoadrenocorticism, or Addison’s disease. Sources: http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/doberman-pinscher#overview https://dpca.org/breed/health/ Photo credit: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/149674387587185244/ https://dogtime.com/dog-breeds/doberman-pinscher#/slide/1

Chlamydophila felis: A Unique Bacteria Causing Diseases to Felines

Chlamydophila felis: A Unique Bacteria Causing Diseases to Felines Maigan Espinili Maruquin Structure and Replication The chlamydiae is unique obligate intracellular bacteria. The Chlamydophila felis is a Gram- negative and rod- shaped coccoid bacterium however the cell wall lacks peptidoglycan (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). It has two morphologically distinct structures. The (1) EB or elementary body is metabolically inert infectious, round and small (~0.3 μm), and is responsible for its survival in extracellular environment with its ‘spore-like’ form with a rigid cell wall. It holds the central and dense nucleoid. Whereas, the other form (2) RB or the replicative but noninfectious reticulate body which is larger (~1 μm) than the EB. It has cross-linked membrane proteins which makes it structurally flexible and osmotically fragile. It contains RNA and diffuse and fibrillary DNA, allowing intracellular replication, nutrient uptake and transportation, protein synthesis and other metabolic activities (Bedson and Bland 1932, Moulder 1991, Nunes and Gomes 2014). The chlamydiae is unique for its biphasic developmental cycle of 30–72 hours (Nunes and Gomes 2014). This bacteria, during its intracellular life, stays in a parasitophorous vacuole, or inclusion to acquire the nutrition it needs. (Hybiske and Stephens 2007). First, the EB attaches and enters the host cell which leads to formation of vacuole. Inside the inclusions, the EB differentiates from the RB. The RB then replicates via binary fission (Borges, V. et. al., 2013) (Nunes and Gomes 2014). The inclusions then expand while RB undergoes transition or conversion back to EB. Finally, the bacteria is released through host cell lysis or via extrusion (Hybiske and Stephens 2007, Nunes and Gomes 2014). Fig. 01. The unique biphasic developmental cycle of Chlamydiae (Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Chlamydia-undergo-a-unique-biphasic developmental-cycle-The-infectious-form-of_fig3_268229035 ) Chlamydophila felis Epidemiology The Chlamydiaceae is reported to have cause animal infection often indirectly and associated with other pathogens (Schautteet and Vanrompay 2011, Nunes and Gomes 2014). The Chlamydophila felis grows in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells and produces inclusion bodies (Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). The C. felis requires close contact between cats to transmit while ocular secretions are considered the most important body fluid for the infection. The disease caused by the C. felis is common in multi- cat environments (Wills JM et al., 1987)(Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) while it is also frequently associated with conjunctivitis (WILLS, HOWARD et al. 1988, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Despite the low zoonotic potential, possible exposure to the C. felis is through handling of infected cats, by contact with their aerosol and also via fomites (Baker 1942, Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). Reports in culture and PCR (Sykes, Anderson et al. 1999, Sykes 2005) showed that C. felis most likely to infect cats less than a year of age and less likely for cats age 5 years above. There is no strong breed or sex preference and prevalence of asymptomatic cases are low (Sykes 2005). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis The C. felis is known to cause conjunctivitis associated with severe swelling of the lid, mild rhinitis, ocular and nasal discharges, fever, and lameness (Masubuchi, K, et al. 2002)(TerWee, Sabara et al. 1998, Rodolakis and Yousef Mohamad 2010). In kittens, chlamydiosis most commonly cause pneumonia and conjunctivitis (TerWee, Sabara et al. 1998, Yan, Fukushi et al. 2000)( Sykes, J. E., 2001)(Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011) and can cause disease to adults, too (Sykes 2005, Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). While C. felis affects conjunctival epithelial cells, natural transmission occurs by close contact with other infected felines, aerosols, and fomites with approximately 3 to 5 days of incubation period (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Generally, conjunctival shedding ceases at around 60 days after infection, however some cats may carry persistent infection (O’Dair HA , et al, 1994; Wills JM., 1986;) (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Due to the reported chlamydial conjunctivitis in the rectal and vaginal excretion from cats, intestinal and reproductive tracts were considered sites for the persistent infections (Wills JM., 1986)(Sykes 2005). On the other hand, findings of the C. felis were also in lung, spleen, liver, kidney and peritoneum of cats (Dickie CW, Sniff ES, 1980; Hoover EA, 1980) (Baker 1944, Masubuchi, Nosaka et al. 2002, Sykes 2005). Other microorganisms may coinfect C. felis. Felines infected by C. felis show clinical signs including: sneezing, transient fever, inappetence, weight lost, nasal discharge, vaginal discharge, lameness and lethargy (Halánová, Sulinová et al. 2011). Unilateral ocular disease may appear during the first day or two which progresses to bilateral. Discharge in the ocular is watery which becomes mucoid or mucopurulent while chemosis can be observed in the conjunctiva. However, although the cats show symptoms after infection, they mostly still continue to eat (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). Fig. 2. A young cat from a multi- cat household showed chlamydial conjunctivitis (Heinrich, C., 2017). (Source: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Bacterial-conjunctivitis-Chlamydophila-felis-Heinrich/12a1d5eee2fbc8121665d94441ff698531c32868 ) Diagnosis Although the use of indirect immunofluorescence can be used to detect the serum antibody titer, this method should be used after a diagnosis of considerable rise in antibody titer (Sykes 2005, Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009). On the other hand, cell culture is considered to be the golden standard in diagnosing chlamydial infections (Pointon AM, et al., 1991) (Wills JM, et. al., 1988) (Sykes 2005). The cell culture technique uses fluorescent antibodies in detecting inclusions. However, cell culture isolation is a demanding, time-consuming and expensive technique while sensitivity of the culture may vary depending on the equipment being used and the technical expertise (Sykes 2005). Further, Giemsa staining can be used for inclusions but this causes confusion with other basophilic inclusions (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) Also, conjunctival smears can be Giemsa stained to look for inclusions, but chlamydial bodies are easily confused with other basophilic inclusions (Streeten BW, Streeten EA, 1985) (Gruffydd-Jones, Addie et al. 2009) and inclusions are often seen only on early infection, and at times, they are not visible (Wills JM, 1986)(Sykes 2005). For a quicker, less expensive and more sensitive diagnosis than cell culture and

Vector-borne disease: Ehrlichia spp. infection

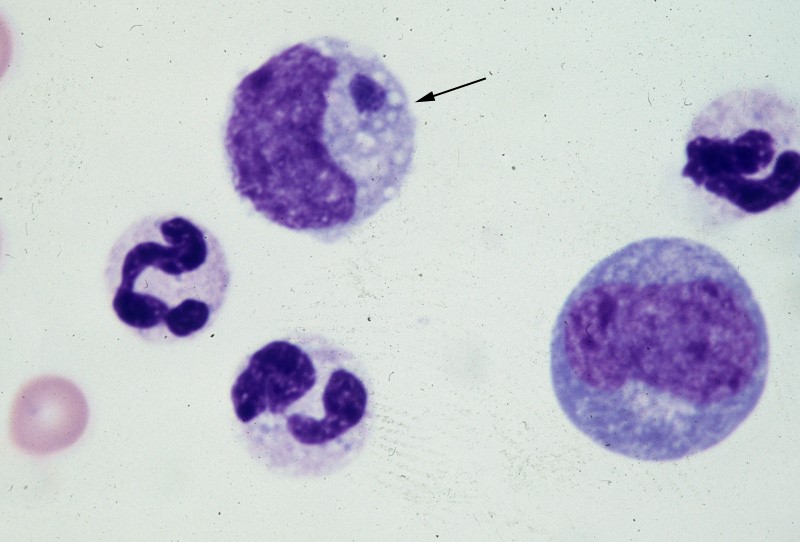

Vector-borne disease: Ehrlichia spp. infection Canine Ehrlichiosis Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D Introduction Ehrlichiosis is a disease of dogs, humans, livestock, and wildlife that is widely distributed around the world and is transmitted by tick vectors. The pathogen of the disease, Ehrlichia, was renamed and classified in 2001 according to the bacterial 16S RNA and groESL gene nucleic acid sequences, and is classified as Rickettsiales, Anaplasmataceae, Ehrlichia genus of bacteria (Allison and Little, 2013).) With global warming, the expansion of tick habitats and the prevalence of cross-border tourism, the chances of the disease spreading to non-endemic areas have increased. How is a dog infected with Ehrlichia? Ehrlichiosis is a disease that develops in dogs after being bitten by an infected tick. In the United States, E. canis is considered endemic in the southeastern and southwestern states, though the brown dog tick is found throughout the United States and Canada. (Photo credit: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/ehrlichiosis-in-dogs) Pathogens and transmission. Ehrlichia spp. are gram-negative, small, obligatory intracellular bacteria. There are currently three types of Ehrlichia spp.: not limited to dogs: Elyse infection, dogs as hosts: E. canis, E. chaffeensis, and E. ewingii. E. canis can infect dogs causing monocytic ehrlichsis (canine monocytic ehrlichsis, CME). Cells most commonly infected by E. canis are monocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 1). CME occurs mainly in tropical and subtropical regions, but there are also cases of infection in other regions. E. chaffeensis infects single-core balls of dogs and humans, mainly in North America, South America, Asia and Africa. E. ewingii is a zoonotic infectious disease that infects particulate white blood cells and is found mainly in North America, South America and Cameroon, Africa. E. ewingii causes human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Bulleretal., 1999). E. chaffeensis infects humans known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis. E. canis also causes human infections (Maeda et al., 1987). Ehrlichia spp. life history is that of vector ticks and mammalian hosts. After sucking the blood of infected animals, the larvae transmit the disease to the new host via saliva when they bite and suck the blood of other animals. E. canis, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii have been shown to mediate life cycle transmission in an intermediary hosts that are usually arthropods. This have shown to stabilize its life cycle transmission, which is also known as Transstadial transmission in arthropods, and blood transfusions or bone marrow may also cause the spread of the disease. The main vector arthropods in E. canis are Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Dermacenter variabilis even though the main host are canines including domestic dogs. Other canine family it can infect are wolves, coyotes, and foxes. The other species, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii consist of hosts from the arthropod family such as Amblyomma americanum, a main vector and other arthropods such as Haemaphysalis, Dermacentor, and Ixodes. E. chaffeensis usually infects white-tailed deer, and E. ewingii to hosts that are likely deer and dogs. Figure 1. Ehrlichia canis in the monocyte (arrow) (Wright’s stain, 1000x) (Source: http://www.eclinpath.com/ngg_tag/infectious-agent/nggallery/page/9) Clinical symptoms. The clinical symptoms and severity of Ehrlichiosis depend on the type of Elysian infection and the host’s immune response. The course of E. canis infection in dogs can be divided into acute, subclinical and chronic, but in naturally infected dogs it is not easy to distinguish between these three stages. If there is a co-infection with other pathogens, it will also aggravate the severity of the disease. The acute period lasts about three to five weeks and can cause fever, poor spirits, loss of appetite, swollen lymph nodes and swollen spleen. Increased eye secretions, pale mucosa, bleeding disorders (bleeding spots, or runny nosebleeds), or neurological symptoms caused by meningitis. Vomiting, diarrhea, lameness, reluctance to walk, stiff pace, and leg or scrotum edema. The most easily observed hematological abnormalities are white blood cell reduction, platelet reduction, and anemia. When clinical symptoms disappear, they are often accompanied by subclinical periods that last for several years (Waner et al., 1997). Although some cases can be fatal, others heal on their own. When a dog is unable to clear the pathogen of infection, the course of the disease develops into a subclinical persistent infection to become a primary dog. Some infected dogs enter a chronic period. During the chronic period, symptoms and hematological abnormalities, including platelet reduction, anemia and total blood cell reduction, all relapse and become more severe than it was during acute periods. When the severity maximizes in a few cases, the dogs will not respond to antibiotic treatment and ceased to heal, and eventually they die from heavy bleeding, severe weakness, or secondary pathogenic infections. Many times, when an infected dog that has contracted E. chaffeensis, the diagnoses points out to other pathogens since there are little information as to E.chaffeensis and dog infections also, the clinical symptoms are similar to that of infection with E. canis. Symptoms include easy bleeding (bleeding spots, blood urine or nosebleeds), vomiting, and swollen lymph nodes. The most common symptom of infection with E. ewingii is fever. Other symptoms include lameness, multiple arthritis, terminal edema, swollen lymph nodes, reduced platelets and anemia, some of which can cause neurological symptoms in dogs. Diagnosis. Ehrlichiosis can be diagnosed by microscopy, serology, or PCR. Diagnosis is complicated when other arthropod-mediated pathogens are used. Blood smears have been observed to infect blood cells to help diagnose the disease. However, this method is time-consuming and can only be observed in a small number of cases during acute infection, so it is not a reliable diagnostic method. Serological examinations are often used to assess Ehrlichiosis. Detection of IgG antibody deposits indicated that dogs had been exposed to pathogens, and two serological examinations two weeks apart during the acute period showed an increase in antibody force prices. Caution should be exercised when a single test result is judged, as healthy dogs may also be antibody positive. Antibodies cannot be detected in the early stages of infection. Additionally, antibodies produced during and after an infection with E.canis, E. chaffeensis, or

Case study: Canine non‐epitheliotropic CD4‐positive cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma: a case report

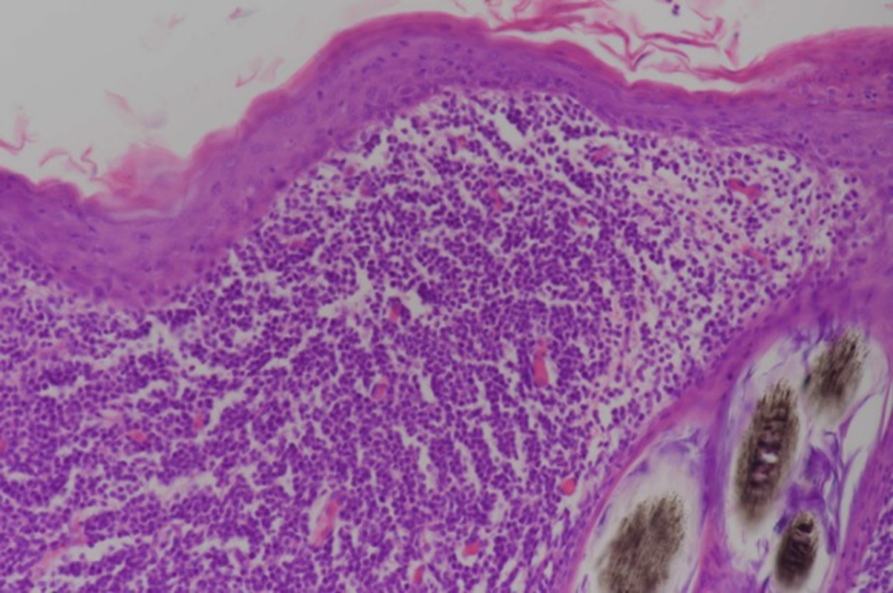

Case study: Canine non‐epitheliotropic CD4‐positive cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma: a case report Robert Lo, Ph.D, D.V.M A 5‐year‐old, spayed female French Bulldog presented with multiple papules on the skin of the scapular area. Histopathological examination of skin biopsy specimens showed proliferated small lymphoid cells in the superficial dermis and in the area around the hair follicle. Immunohistochemical examination revealed that these cells were positive for CD3, CD4 and TCRαβ antibodies, but negative for CD1c, CD8α, CD8β, CD11c, CD20, CD45RA, CD90, MHC-II and TCRγδ antibodies. In addition, CD45 is highly expressed, and proliferation is very low. The genetic recombination test of the T cell receptor G chain detects the proliferation of recombinant clones. Skin lesions were removed by surgery because of progressing to the outside of the forelegs. The postoperative clinical course was good, and no recurrence was observed until the dog died in a traffic accident about a year later. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6498901/ Figure 1 Clinical features of the dog. Multiple papules are present on the right scapular area. Figure 2 Histopathological features of the lesion. Small lymphoid cells are proliferative at the superficial dermis and the perifollicular areas. Figure 3 Immunohistochemical analysis via the avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex method. Dense infiltration of CD4‐positive small lymphoid cells is evident at the superficial dermis. Bar = 200 μm.