Breed-related disease: German Shepherd

The German Shepherd is a breed of medium to large-sized working dog that originated in Germany, Intelligent as it is versatile, this breed was originally developed in Germany to guard and herd a shepherd’s flocks. It has a double coat, which is comprised of a thick undercoat and a dense, slightly wavy or straight outer coat. Its hair, usually tan and black, or red and black, is medium in length and is shed all year round. Other rarer color variations include all-Black, all-White, liver and blue. The German Shepherd’s body is long-generally between 22 and 26 inches-in proportion to its height. This gives the dog strength, agility, elasticity and long, elegant strides. Because this watchful, self-assured breed is nearly unmatched in intelligence, German Shepherds excel in high-pressure jobs that require next-level problem solving, like search and rescue or police work. These extremely confident dogs are also keen observers and thinkers who have an uncanny ability to make decisions and problem-solve on the fly. They’re lauded for their courage, which is another trait that makes them a versatile working companion. Though German Shepherds might seem aloof around strangers, they bond easily with their families and are incredibly loving companions. The German Shepherd has an average lifespan of between 10 to 12 years. It is, however, susceptible to some serious health conditions like: Perianal Fistula: which is a disorder most commonly seen in German Shepherds. The disease is characterized by draining openings on the skin around the anus. Affected dogs may strain to defecate, have diarrhea or bloody stool and lick at the anal area frequently Megaesophagus: (from the Greek Mega meaning large) is a condition in which the esophagus (the tube that carries food to the stomach when we swallow) becomes limp and is not able to normally pass the food on its way to be digested. The type of megaesophagus that we see in German Shepherds is a congenital problem that a recent study found to correlate to chromosome 12. Affected dogs often begin to show signs, vomiting and regurgitation when they are weaned to a solid diet. Hip Dysplasia: Most people by now know about hip dysplasia. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint and hip dysplasia causes malformation of the components leading to instability. There can be abnormalities in either the ball or the socket (or both) and the chronic laxity causes abnormal wear and leads to osteoarthritis. Degenerative Myelopathy : is a neurologic disease and is a recessive genetic disorder in the German Shepherd Dog. Affected dogs are usually middle-aged or older patients and this disorder are difficult to distinguish from other causes of spinal cord compromise like intervertebral disc disease found commonly in many types of dogs. This genetic cause of weakness and paraplegia can only be positively identified postmortem with a histological exam of spinal cord tissue. Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI): This disorder of the digestive system is potentially life-threatening (particularly in its acute form) but often responds well to treatment. It is more common in some breeds than others and is frequently seen in German Shepherd Dogs. Sources: https://www.petmd.com/dog/breeds/c_dg_german_shepherd https://iheartdogs.com/ask-a-vet-what-are-5-important-health-concerns-for-german-shepherd-dogs/ Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Shepherd https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/german-shepherd-dog

Breed-related disease: Siberian cat

The Siberian is a centuries-old landrace (natural variety) of domestic cat in Russia, and recently developed as a formal breed with standards promulgated the world over since the late 1980s. As befits a cat from northern Russia, the Siberian wears a magnificent fur coat that not only protects him from the elements but also gives him a glamorous appearance that belies his gentle good nature. At first glance, the Siberian resembles the Maine Coon and the Norwegian Forest Cat, but he is differentiated by having a more rounded body and head. He also stands out for his large yellow-green eyes, tufted ears and neck ruff. The Siberian coat comes in many colors and patterns, but brown tabbies seem to be most popular. The Siberian cat is highly affectionate with family and playful when they want to be. However, their exercise needs aren’t overly demanding, and they’re just as happy to snuggle up with their humans as they are to chase a laser toy–maybe even happier. In Russia, the phrase Siberian health is associated with vitality, longevity, and ability to stay healthy despite the frigid climate of the Siberian region. This saying is very true when it comes to Siberian cats. Siberians tend to be sturdy, healthy and, while being purebred cats, do not present the owner with too many health issues. However, there are some health problems typical for cats in general, and for Siberians in particular. If you own a Siberian cat or kitten or are only planning to adopt one, it’s best to know ahead what types of health issues you may encounter, and how to help your cat overcome them. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy : This is a heart condition in which the walls of the heart are thicker than they should be. Instead of benefiting from a stronger heart, this condition makes it more difficult for the cat to pump blood to the rest of the body. Kidney Disease (PKD): It is a genetic mutation that leads to the development of benign cysts in the cat’s kidneys and other organs. It is a hereditary disease that’s fairly common for Siberian cats. Gum Disease: Many Cat Owners overlook the importance of dental hygiene in their furbabies, but with this breed, regular teeth brushing is crucial. Hereditary Cancer: Cancer is by far most common in the white Siberian Forest Cats, and can be linked to a specific pedigree lineage of “Gesha Olenya Krasa” and “Dolka Olenya Krasa”. Cats of this descent are known to have cancer-causing genes , known as oncogenes. However, as in most other animals with oncogenes, the presence of the gene doesn’t necessarily guarantee the presence of cancer, and other factors may help prevent its manifestation such as a healthy diet and regular checkups. Urinary Tract Disease: Also referred to as Urinary Crystals, the condition involves the formation of stone-like minerals, crystals and organic matter and reside in the cat’s urinary tract. This covers anything from kidney stones to blockages to infections of the kidney. Although it’s not completely known whether it’s completely hereditary, it’s very common in the Siberian Cat. Sources: http://www.vetstreet.com/cats/siberian https://www.siberiancatworld.com/siberian-cats-health-problems/ http://aubreyamc.com/feline/siberian/ https: //www.madpaws .com.au / blog / siberian-cat / Photo credit: https://cattime.com/cat-breeds/siberian-cats#/slide/1 https://cats.lovetoknow.com/Siberian_Cats

Understanding FPV and its Threat to Our Cats

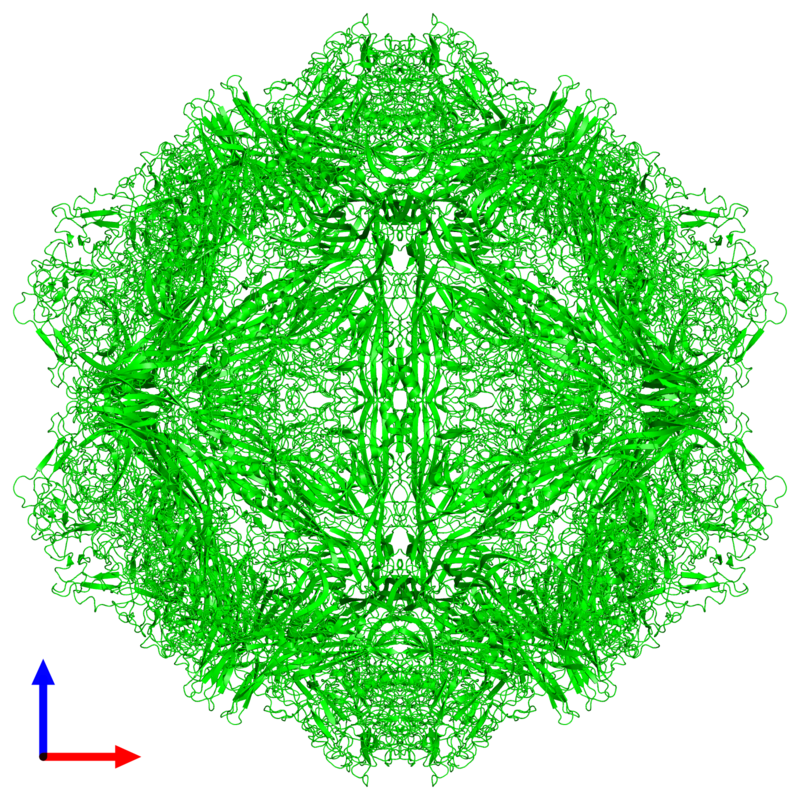

Understanding FPV and its Threat to Our Cats Maigan Espinili Maruquin The Feline Panleukopenia (FPL) is an important disease in cats. It is highly contagious and is often fatal to cats (Van Brussel, Carrai et al. 2019). This is caused by feline parvovirus (FPV; formerly FPL virus) and canine parvovirus (CPV), however, CPV infections in cats are uncommon (Barrs 2019). The FPL is also known to be the oldest known viral disease in cats wherein several epizootics that killed domestic cat populations in the 1800s could have been infected by FPV (Fairweather 1876, Barrs 2019) (Scott FW, 1987). Structure Fig. 01 A front view 60- meric assembly of FPV by Protein Data Bank in Europe containing 60 copies of Capsid protein VP1 ( https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/1fpv ) The current taxonomic entity of FPV shares with CPV (Tattersall, 2006) wherein after crossing species barriers, CPVs evolved from FPV by acquiring five or six amino acid changes in the capsid protein gene (Truyen, 1999) (Appel, Scott et al. 1979, Black, Holscher et al. 1979, Osterhaus, van Steenis et al. 1980, Parrish 1990, Johnson and Spradbrow 2008, Stuetzer and Hartmann 2014, Barrs 2019). The causative agent FPV is a member of the genus Protoparvovirus in the family Parvoviridae with 5.2 kb long single stranded DNA genome, containing two open reading frames (ORFs): the first ORF encodes two non-structural proteins, NS1 and NS2; and the second ORF encodes two structural proteins, VP1 and VP2 (Reed, Jones et al. 1988, Zhou, Zhang et al. 2017). At first, FPV was thought not to infect cats (Truyen, Evermann et al. 1996). It replicates in thymus and bone marrow but not within the intestinal tract of dogs (Truyen and Parrish 1992, Truyen, Gruenberg et al. 1995). The pathway of viral entry into cells is not fully characterized, however through the feline transferrin receptor (TfR), FPV binds and uses the receptor to infect feline cells (Parker, Murphy et al. 2001, Hueffer, Govindasamy et al. 2003). However, CPV-2b and CPV-2c variants emerged, with only a single amino acid position different from CPV-2a, and infect cats both naturally and experimentally (Mochizuki, Horiuchi et al. 1996, Truyen, Evermann et al. 1996, Ikeda, Mochizuki et al. 2000, Nakamura, Sakamoto et al. 2001, Gamoh, Shimazaki et al. 2003, Decaro, Desario et al. 2011, Zhou, Zhang et al. 2017, Van Brussel, Carrai et al. 2019). FPV Infection The virus may be shed in feces even in the absence of clinical signs (subclinical infections), or before clinical signs are detected (Barrs 2019). The major portals of the FPV are the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and, less commonly, the respiratory tract. Generally, CPV is an uncommon cause of FPL and to date, no large-scale outbreaks of FPL have been confirmed to be caused by CPV (Barrs 2019). There were cases of indistinguishable CPV from FPV clinical signs in several cats (Mochizuki, Horiuchi et al. 1996, Miranda, Parrish et al. 2014, Byrne, Beatty et al. 2018, Barrs 2019). Moreover, coinfections of CPV and FPV were also reported in cats with clinical disease (Battilani, Balboni et al. 2011, Battilani, Balboni et al. 2013, Barrs 2019). The FPV can remain latent in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy cats with high virus-neutralizing titers (Ikeda, Miyazawa et al. 1999, Miyazawa, Ikeda et al. 1999, Nakamura, Ikeda et al. 1999, Barrs 2019). The development of immunity of an unvaccinated cat to FPV is likely to increase with age (DiGangi, Levy et al. 2012). However, FPL mostly infects unvaccinated and incompletely vaccinated kittens. The age susceptibility correlates with the declining maternally derived antibodies (MDAs) as well as “the immunity gap” in incompletely vaccinated kittens (Barrs 2019). Clinical Signs/ Pathogenesis The FPV is resistant to heating (80C for 30 min) and low pH (3.0) (Goto, Yachida et al. 1974). Virions enter cells by endocytosis (Hueffer, Palermo et al. 2004). Viral DNA is released from the capsid and replicates through double-stranded RNA intermediates in the nucleus of the cell using the host’s DNA polymerase (Barrs 2019). It can be transmitted by the faecal-oral route and a contact with infected body fluids, faeces, or other fomites, as well as by fleas primarily spreads the virus. Viral replication primarily occurs in lymphoid tissue, bone marrow and intestinal mucosa in infected cats older than 6 weeks of age (Csiza, De Lahunta et al. 1971, Csiza, Scott et al. 1971, Parker, Murphy et al. 2001). Infection outcome ranges from subclinical to peracute infections with sudden death within 12 h (Stuetzer and Hartmann 2014). Initially, non-specific signs such as fever, depression, and anorexia during the acute stage (Addie, Jarrett et al. 1996). However, vomiting unrelated to eating occurs commonly and, less often, cats develop watery to haemorrhagic diarrhoea later in the course of disease, while some cats show extreme dehydration. Cats typically die of complications. Viral DNA can persist for long periods even after infectious virus has been lost, thus detection of DNA does not necessarily signify an active infection (Stuetzer and Hartmann 2014). Utero infection in early pregnancy can result in foetal death, resorption, abortion, and mummified fetuses while in later pregnancy may damage the neuronal tissue. The main clinical signs of FPV infection for new- born kittens include neurological, with ataxia, hypermetric movements and blindness, while some also shows signs of cerebellar dysfunction, forebrain damage (with seizures) with a range of severity and neurological signs. Although some kittens acquire MDAs, they can still get the virus for up to 2 months after birth (Csiza, Scott et al. 1971, Csiza, Scott et al. 1971, Stuetzer and Hartmann 2014). Infections occurring up to 9 days of age can also affect the cerebellum. Cats having mild cerebellar dysfunction may retain good quality of life. On the other hand, FPV can also cause retinal degeneration in infected kittens, with or without neurological signs (Percy, Scott et al. 1975, Stuetzer and Hartmann 2014). Diagnosis It is important to have the FPV detected early using accurate testing methods to prevent disease transmission