Rapid Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing to Combat Resistance

Table of Contents 1. Introduction: Defining Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) is a crucial diagnostic procedure used to guide the treatment of infectious diseases. It provides evidence-based data that allow clinicians and veterinarians to identify the most effective antibiotics for treating specific bacterial infections while minimizing the risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). 1.1 Purpose in Clinical and Veterinary Diagnostics AST is an in vitro laboratory method used to determine which antibiotics are effective at inhibiting the growth of a given bacterial isolate. In clinical microbiology, it functions as a vital extension of the diagnostic process, translating laboratory findings into actionable treatment decisions. The fundamental objectives of AST are threefold: Confirm Susceptibility: To verify that a bacterial isolate is sensitive to the chosen empirical antimicrobial agents. Detect Resistance: To identify emerging or established resistance mechanisms within the isolate. Guide Therapy: To provide clinicians with data that support targeted, rational antimicrobial selection. Although most applications are in human medicine, the relevance of AST extends to veterinary and agricultural diagnostics, where inappropriate or preventive antibiotic use in food and animal industries accelerates the development of resistance. Incorporating AST into these sectors is therefore essential for achieving a One Health approach that integrates human, animal, and environmental health management. 1.2 Role in Identifying the Most Effective Antibiotic AST ensures that patients receive the most appropriate and targeted antibiotic therapy. The process combines quantitative and qualitative assessments of bacterial growth inhibition, allowing for the identification of the most suitable antimicrobial agent. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC):A primary output of AST is the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), defined as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic required to inhibit visible bacterial growth in vitro. Determining Efficacy:MIC values are interpreted to determine whether the bacterial isolate is susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to a given antibiotic. Standardization and Global Guidelines:The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) establish standardized interpretive breakpoints that guide laboratory and clinical decisions globally. Integration for Complete Diagnosis:The diagnostic value of AST is maximized when combined with accurate bacterial identification. This integration enables physicians and veterinarians to administer the narrowest effective antibiotic for the identified pathogen, optimizing therapeutic outcomes and minimizing ecological impact. 1.3 Supporting Antimicrobial Stewardship and Reducing Misuse AST forms the cornerstone of antimicrobial stewardship, the coordinated effort to preserve antibiotic efficacy by promoting rational use. The global threat of antibiotic resistance, which currently contributes to an estimated 700,000 deaths annually, underscores the urgency of this practice. Reducing Broad-Spectrum Dependence:In many clinical scenarios, delays in diagnostic confirmation lead clinicians to initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics empirically. This practice, while often necessary, fosters selective pressure that accelerates resistance. Enabling Rapid, Targeted Treatment:Improvements in AST turnaround time and the adoption of rapid testing methods allow faster initiation of effective targeted therapy, reducing unnecessary broad-spectrum exposure. Improving Clinical Outcomes:Timely susceptibility results enable healthcare professionals to transition from empirical to pathogen-directed therapy. This precision approach improves patient recovery, reduces adverse effects, and contributes to long-term containment of resistance. 2. Principles and Methods of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) encompasses a range of laboratory methods designed to determine the ability of bacteria to grow in the presence of specific antimicrobial agents. These techniques are broadly divided into phenotypic methods, which measure the observable inhibition of bacterial growth, and genotypic methods, which detect genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance. 2.1 Phenotypic Methods Phenotypic testing remains the gold standard for AST in clinical and veterinary microbiology. These methods directly assess bacterial growth inhibition and provide either qualitative or quantitative results based on visible morphological changes. Disk Diffusion (Kirby–Bauer Test) The disk diffusion method, commonly known as the Kirby–Bauer test, is one of the most widely used AST procedures worldwide due to its convenience, low cost, and standardized interpretive criteria. Principle and Procedure:Sterile paper disks impregnated with fixed concentrations of antibiotics are placed on the surface of an agar plate uniformly inoculated with the bacterial isolate. Following incubation (typically 16–24 hours at 35 °C), bacterial growth is inhibited around the disk, forming a zone of inhibition. Interpretation:The diameter of the inhibition zone is measured and compared with reference standards provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) or the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). The isolate is categorized as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on these standardized breakpoints. Advantages and Limitations:The disk diffusion test allows simultaneous testing of multiple antibiotics but provides qualitative results only, as it does not yield an exact Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). Broth Dilution (Macro and Micro Methods) Broth dilution techniques determine the MIC, defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits visible bacterial growth. Macrobroth (Tube) Dilution:This traditional method involves preparing serial two-fold dilutions of antibiotics in test tubes containing a liquid growth medium. After inoculation and incubation at 35 °C, tubes are examined for turbidity. The lowest concentration preventing visible growth represents the MIC. While reliable, this approach is labor-intensive and time-consuming, limiting its routine clinical use. Broth Microdilution:This method miniaturizes the macrobroth technique using 96-well microtiter plates, allowing the simultaneous testing of multiple antibiotics and bacterial isolates. Each well contains a defined concentration of antibiotic and a standardized inoculum. After incubation, bacterial growth is assessed visually or via automated readers. Automation: Broth microdilution forms the foundation of most automated AST systems, which have been in routine diagnostic use since the 1980s. Systems such as VITEK® 2, BD Phoenix™, Sensititre™, and MicroScan WalkAway® automate sample handling, incubation, and interpretation, improving standardization and efficiency. Turnaround Time: Although miniaturized, conventional broth microdilution typically requires similar incubation times to macrobroth methods (16–24 hours). E-test (Gradient Diffusion Method) The E-test provides a semi-quantitative estimate of the MIC by combining diffusion and dilution principles. Principle and Procedure:A plastic strip impregnated with a continuous antibiotic gradient is placed on an agar plate inoculated with the test organism. After 18–24 hours of incubation, an elliptical inhibition zone forms around the strip. Interpretation:The MIC is read directly from the point on the scale where the inhibition

Canine Parvovirus

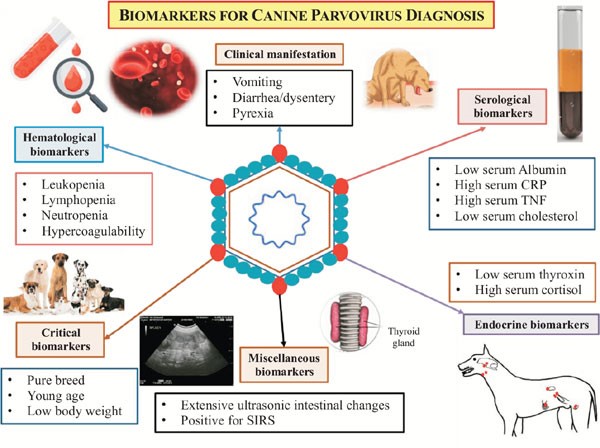

Canine Parvovirus CHINESE EDITION IS WRITTEN BY DR. WANG, SHIH-HAO / ENGLISH EDITION IS TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY DR. LIN, WEN-YANG (WESLEY) Abstract The canine parvovirus (CPV) is a common, acute, high morbidity and high morality virus that mainly infect canine population. This virus possess highly survival rate for 5 weeks in the natural environment. It is highly contagious and easily transmitting among canine population by the fecal-oral route through contacting contaminated feces. CPV usually attack digestive system. Sometimes it may induce myocarditis among canine and cause sudden death. All ages, sexes and breeds of dogs could be susceptible to CPV, especially puppies. Clinical sighs of infected dogs may include fever, lethargy, continuous vomiting, continuous diarrhea, stinky viscous diarrhea with blood, dehydration and abdominal pain etc. Canine show signs of the disease would usually die within 3 to 5 days. There are no specific drugs for curing CPV until now. Supportive care such as consuming water-electrolyte fluid is the only present solution to maintain physiological function and relieve symptoms. The infected canine should have medical care as soon as possible; otherwise, more severe conditions like acute dehydration, hypovolemic shock, bacterial infections and death will occur. Infection prevention measures include environmental disinfection and routine vaccines. Pathogens The canine parvovirus (CPV) is an ssDNA virus, which belongs to the species carnivore protoparvovirus 1 within the genus protoparvovirus in the family parvovirus (parvoviridae). CPV is 98% identical to feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV) with variant in six coding nucleotide of structural proteins VP2: 3025, 3065, 3094, 3753, 4477, 4498 that makes CPV-2 infect canine host instead of replicating in cats. Two types of canine parvovirus were discovered – canine minute virus (CPV1) and CPV2, both can attack canine population and canidae family such as raccoons, wolves and foxes. Canine parvovirus may be susceptible to cats without pathogenic, and it is an inapparent infection. CPV2 could stably survive in feces for 5 months with ideal condition. Furthermore, CPV-2a, CPV-2b and CPV-2c type viruses have been isolated and sequenced from animals. Other than targeting on canine, large cats are susceptible to CPV-2a, CPV-2b. CPV-2c type viruses have high prevalence on infecting leopard cats. Figure 1. Model of CPV evolution showing VP2 amino acid differences between each virus and indicating the virus host ranges. (Karla M. Stucker, Virus Evolution In A Novel Host: Studies Of Host Adaptation By Canine Parvovirus, Published in 2010) Epidemiology In 1978, a novel infectious canine disease was firstly occurring in the east coast of America. Within 12 months, scientists identified CPV-2 as the aetiological key of severe symptoms among canine. Due to characters of highly contagious and potential environmental resistance, CPV-2 spread swiftly over entire USA, European countries, Australia and Asia. In 1978, canine parvovirus also invade among canine in Taiwan. Therefore, CPV caused large scale of canine death at the early stage of pandemic. By the establishment and development of CPV vaccine, global wide spreading of CPV has been rarely happen today. However, canine parvovirus still widely exists in domestic dogs and wild canidae. It became one of the canine endemic disease. Pathogenesis Incubation period of CPV-2 lasts 4 to 5 days. The virus mostly attacks rapidly dividing cells especially lymphopoietic tissues, the bone marrow, crypt epithelia of the jejunum, ileum and (in young dogs under 4 weeks old) myocardial cells. Rottweilers, black Labrador Retrievers, Doberman Pinschers, and American Pit Bull Terriers are more susceptible than other species; once they are infected, would suffer severer conditions. Besides, CPV-2 take the major place to affect canine and wild canids. After entering into hosts’ body, CPV-2 firstly replicates in oropharynx lymphoid tissues, mesenteric lymph nodes and thymus gland, then spreading to other lymph nodes, lung, liver, kidney and rapidly dividing tissues (e.g. bone marrow, intestinal epithelial cell and myocardial cell) by the blood stream. 4 to 5 days after, clinical sighs like diarrhea, vomiting, lymphopenia, anorexia, depression, dehydration, hypothermia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia would appear. Severe dehydration and hypovolemic shock may happen due to lose large amount of fluid and protein by vomiting and diarrhea. Transmission Fecal-oral route is the main transmission pathway of CPV-2. Large amount of virus would be detected in feces of infected canine within 1 to 2 weeks of acute phase. An infected pregnant canine could transmit virus to fetus through placenta. Fomites include contaminated shoes, cages, food bowls and other utensils could serve as CPV transmitting objects also. Clinical forms There are four clinical forms according to distinct signs and lesions: enteric, myocardial, systemic infection and inapparent Infection. A. Enteric form : It is known that CPV-2 caused enteritis symptoms. This form infect host with low virus titers (around 100 TCID50). Symptoms in initial stage are sopor, loss of appetite, acute diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, slight elevated body temperature, frailty and acting like in extreme pain. Severity of illness vary according to the age of canine, healthy condition, infectious dose of the virus, and other pathogens in intestine and so on. Typical signs of CPV induced enteritis and its course include loss of appetite, sopor, fever (39.5℃-41.5℃) within 48 hours follow vomiting. 6 to 24 hour after vomiting follow watery stool in yellow or white color, mucus stool or bloody stool with stench in severe cases. Due to consistent diarrhea and vomiting, dogs suffer worsen dehydrated condition. Common clinical pathologic examination consist assessing dehydrated condition and significant decreasing of white blood cell of dogs (400 to 3000 /μL). B. Myocardial form: This form only appear in puppies around 3 to 12 weeks of age. Major cases show pups’ age under 8 weeks. Mortality rate is extremely high with myocardial form (almost up to 100%). Clinical signs include irregular breathing, cardiac arrhythmia. Collapse, hard breathing may happen to acute cases follow death within 30 minutes. Most cases would die within 2 days. The subacute form would also die from hypoplastic heart syndrome within 60 days. Nevertheless female adult canine acquire antibodies against myocardial form by vaccination or infection, puppies may

Peritonitis in Dogs: Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment Insights

Table of Contents 1. Introduction to Peritonitis and Septic Peritonitis (SP) Definition of Peritonitis Peritonitis in dogs refers to the inflammation of the peritoneum, the thin serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity and envelops the visceral organs. When this inflammation is accompanied by microbial contamination, the condition progresses to septic peritonitis (SP), a complex, rapidly progressive, and life-threatening disease. SP represents a convergence of local peritoneal inflammation and systemic infectious insult, frequently culminating in sepsis or septic shock without timely intervention. Relevance Across Mammalian Species The pathophysiological patterns of septic peritonitis exhibit strong parallels across mammalian species. Data derived from canine, feline, and human literature suggest similar clinical trajectories and diagnostic challenges: Canine–Feline Parallels:Evidence indicates that clinicopathologic abnormalities and outcomes in feline SP mirror those documented in dogs, reinforcing the cross-species applicability of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Human Literature as a Clinical Framework:Human medicine, with its extensive sepsis research, provides a valuable framework for veterinary clinicians. The early adoption of Procalcitonin (PCT) as a biomarker in dogs reflects its well-established role in human sepsis diagnosis.The central mechanism, an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune responses, is widely corroborated by human critical care studies and applies equally to canine SP. Peritonitis Arises Most Commonly from Infection and Perforation Microbial contamination of the peritoneal cavity most frequently results from gastrointestinal perforation, loss of mucosal integrity, or traumatic breach of sterile abdominal compartments. Microbial Etiology Gram-negative organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, predominate in septic abdominal infections: In one study of dogs with septic peritonitis: 39 percent of abdominal cultures yielded only gram-negative bacteria, 28 percent yielded only gram-positive organisms, and 33 percent demonstrated mixed gram-negative and gram-positive infections. Common Sources of Contamination Septic peritonitis is usually linked to a definable intra-abdominal lesion or event: Gastrointestinal leakage, including dehiscence of enterotomy or enterectomy sites, remains one of the most frequent causes. NSAID-induced perforation: Meloxicam-associated colonic perforation is documented, marked by full-thickness ulceration and underlying vascular thrombosis, culminating in diffuse septic peritonitis. Parasitic migration and necrosis: Aberrant migration of Spirocerca lupi may induce acute mesenteric ischemia-like lesions, leading to segmental necrosis, infarction, and SP. In one case series, all affected dogs were ultimately diagnosed with septic peritonitis. These pathways highlight the diversity of initiating events while reinforcing the consistent pathogenic mechanism, the introduction of bacteria or fungi into a previously sterile compartment. Importance of Rapid Recognition and Progression Toward Shock Septic peritonitis is characterized by abrupt clinical deterioration. Early recognition and decisive intervention are central to improving survival. Life-Threatening Pathophysiology Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction arising from a dysregulated host response to infection. SP is a major precipitating cause of sepsis in veterinary practice. Rapid Clinical Decline The literature consistently stresses the importance of early diagnosis: Delayed detection directly decreases survival, as timely intervention is essential for controlling contamination and stabilizing systemic physiology. Dogs with bacterial SP frequently fulfill Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria due to their pronounced inflammatory cascade. Progression to Septic Shock SP-associated sepsis may escalate to septic shock, defined by: Persistent arterial hypotension despite aggressive fluid resuscitation Requirement for vasopressor therapy to achieve adequate perfusion pressure In one study, 25 percent of dogs with bacterial sepsis progressed to septic shock requiring vasopressors, reflecting the severe systemic compromise associated with SP. Mortality and Organ Dysfunction Survival outcomes correlate strongly with: The number of organ systems affected, and The severity of organ dysfunction, often progressing to Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS). Even with appropriate surgical and medical management, only approximately half of affected dogs survive to hospital discharge, underscoring the lethal nature of this condition. 2. Etiology and Pathophysiology The etiology and pathophysiology of peritonitis, particularly the infectious variant known as septic peritonitis (SP), describe a cascade in which localized abdominal contamination progresses toward systemic inflammatory crisis. Across studies in dogs, this transition is consistently associated with high morbidity, rapid deterioration, and the need for aggressive diagnostic and surgical intervention. 2.1 Overview of Pathogenesis Septic peritonitis is considered a complex, life-threatening condition, initiated by microbial contamination of the peritoneal cavity and sustained by a dysregulated inflammatory response requiring urgent perioperative management (Mueller et al., 2001). Microbial Contamination of a Sterile Space The entry of bacterial or fungal pathogens into the previously sterile peritoneal cavity represents the defining initiating event. Most common pathogens:Gram-negative organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, are the predominant cause of abdominal sepsis in dogs (Costello et al., 2004). Culture patterns:In one study of canine SP, 39 percent of abdominal effusion cultures yielded only gram-negative bacteria, 28 percent only gram-positive, and 33 percent yielded both, demonstrating the polymicrobial nature of abdominal contamination (Mueller et al., 2001). Sources of Contamination Peritoneal contamination may arise through multiple mechanisms: Surgical Dehiscence The most common cause of SP in dogs in a retrospective study (43 dogs) was dehiscence of an enterotomy or enterectomy site, indicating failure of previous surgical repair (Costello et al., 2004). Ulcer Perforation (NSAID-Induced) Colonic perforation resulting in generalized septic peritonitis has been linked to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) administration, notably meloxicam. Histopathology typically shows full-thickness ulceration, inflammatory infiltration, and perforation with thrombosed vessels at ulcerated sites (Kine et al., 2019). Parasite-Induced Rupture and Ischemia Acute mesenteric ischemia-like syndrome due to suspected Spirocerca lupi aberrant migration causes severe mesenteric vascular thrombosis, intraluminal parasite larvae, and segmental intestinal necrosis. All dogs in one case series ultimately developed septic peritonitis as a result (Lerman et al., 2019). Other Septic Sources Reported infectious causes of systemic sepsis in small animals include: generalized septic peritonitis, pneumonia, pyometra, septic bile peritonitis, and necrotising fasciitis (DeClue et al., 2011). Inflammatory Cascade and Systemic Crisis Once microbial contamination occurs, a pronounced inflammatory cascade leads to: exudation and vascular leakage, accumulation of protein-rich abdominal effusion, endotoxin-driven vascular instability, and systemic toxemia. Sepsis develops when this inflammatory response becomes dysregulated, producing an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (Culp et al., 2009). The resulting pro-inflammatory shift damages tissues, promotes coagulopathy, disrupts perfusion, and accelerates multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Septic shock is